March 2010

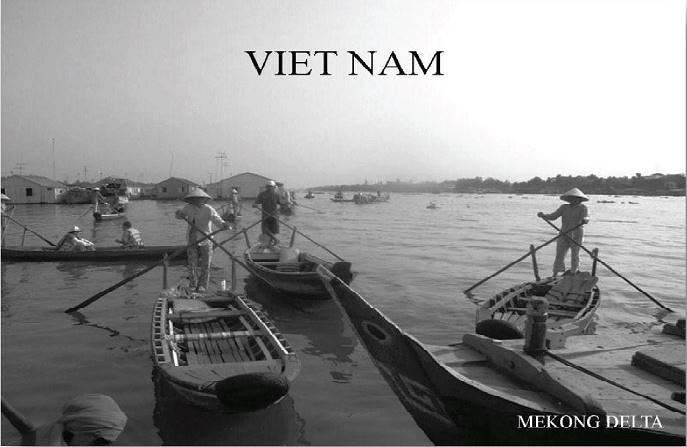

Though I had been in Viet Nam five years earlier traveling north to south, I looked forward to having a second opportunity in Hồ Chí Minh City (formerly Saigon), a bustling international port with a population of 8 million people, as well as to seeing areas of the Mekong Delta new to me. I was not disappointed.

We flew Vietnam Airways from Vientiane, Laos to Phnom Penh, Cambodia, as there was no direct flight to our destination. The first leg of the trip took an hour and 20 minutes, the second only 30 minutes following a short wait in the transfer lounge.

Hồ Chí Minh City is a busy, sprawling city that is hot and steamy year-round. The constant stream of motorbikes offers a spectacle of people in conical hats, caps, helmets, and scarves; high school girls in white áo dàis; and women in long gloves and fashionable face covers for sun protection. Half of the one million Chinese in Viet Nam live in Saigon, as the city is still called by locals. “Sài Gòn” means “land of the gon tree.” Vietnamese, like Chinese, is made up of single-syllable units of meaning. “Nam” means “south”; “Viet Nam” refers to people of the Viet ethnic group living to the south of China. The government used to forbid putting only English names on stores; signs appeared in large Vietnamese words, followed on a second line by smaller English translations. Still, western companies seemed to have made major inroads.

Our city tour began with the War Remnants Museum. Compared to five years earlier, it now seemed more crowded with visitors. Remnants of assorted bombs and planes used by the Americans are displayed on the museum grounds; local visitors enjoy posing for souvenir photos in front of these pieces. The indoor displays are of photographs and journals depicting both warring sides. Factual information recalls that 3 million Vietnamese were killed, and 4 million others injured, and that 58,000 American soldiers died in the war. By the time I had gone through the museum, I had a big lump in my throat and knots in my stomach, just as I had had after my first visit.

A visit to a market was an incredible sensory experience. Women vendors surrounded by bags of goods sipped tea to keep cool and fanned themselves in tiny stalls. Aromas of sweets, dried papaya strings, and coconut mixed with the smell of dried fish. Mounds of local fruit such as mangoes, jackfruit, rambutan, and durian vied for our attention as shoppers tried to make their way through the narrow lanes, which were also stacked with household goods and clothing. Manicure and pedicure business was brisk.

The majestic Post Office, the Notre Dame Cathedral, and the Opera House are legacies of the French colonial period, along with other buildings lining Saigon’s wide boulevards. New hotels — such as the Novotel, Sheraton, and Hyatt — dot the skyline. Jewelry stores and boutiques glitter into the night. However, the maddening intensity of motorbikes heeding no traffic regulations discourages extensive walking.

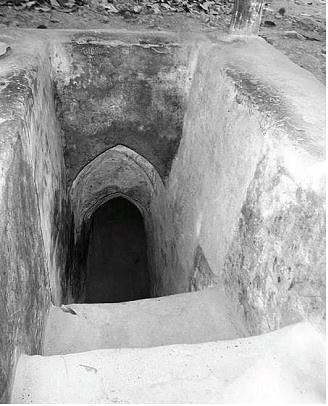

Tunnel entrance

The next day’s visit to the Củ Chi Tunnels began with a documentary film. This underground maze of tunnels was first dug in 1945 to serve in the fight against the French, and was expanded over 25 years by the Viet Cong. Spanning 125 miles, the multi-level tunnels hid thousands of fighters and villagers while the country was at war with the Americans. We went down through a narrow opening widened for tourists, where we saw an operating room, a meeting room, a mess hall, and a kitchen. Smoke from the kitchen was deflected into bamboo chimneys that doubled as traps, causing victims to fall in when pulled. Doors between tunnels prevented poisonous gas poured in by the enemy from traveling to other units.

The tunnels narrowed at the center to capture Americans who were successful in entering. The Viet Congs’ small frames as opposed to the Americans’ big stature played a role in strategic planning. Women worked in the tunnels during the day and in the rice fields at night in order to feed the soldiers. They dipped rice rolls in crushed peanuts to provide protein. Since my previous visit, I found the bunkers had become easier to access and in general more visitor-friendly; the souvenir shops had tripled in size and number. The tunnels are a vivid testament to the ingenuity and perseverance that eventually helped the Vietnamese win the war, and are definitely worth a visit.

On the way back we stopped by a forest of rubber trees. These trees, planted in neat rows, have a life span of 40 years. Just before the rainy season, the bark is scored for the sap to drain into clay pots tied to the trees. Several times a day the pots are emptied and the rubber taken to a latex factory to be used in the manufacture of tires, mattresses, and other products. Rubber is Viet Nam’s main export item, along with crude oil, rice, coffee, tea, garments, and shoes.

Rice paper drying

on bamboo screens

Visiting a family business for making rice paper was the beginning of a culinary adventure. Women spread boiled rice flour thinly over a hot plate until it formed a round film of dough, which then was wrapped around a wooden dowel and spread on a bamboo screen to dry. Lunch was at the Saigon Culinary Art Center. The menu consisted of dumplings with shrimp, a lotus stem salad with pork and shrimp, braised chicken with ginger, sour soup with ginger, steamed rice, tropical fruit, and tea. Everything was delicious.

A visit to the Tayson Lacquer Shop helped us to understand the complex and time-consuming craft of lacquerware production. The process of making an object begins with bamboo being split and coiled into a traditional shape, which is then coated with a lacquer paste made of sap from a tree indigenous to Southeast Asia. The bamboo is then cured for a week in a dark, humid room. After several lacquer coats alternating with week-long cures, the object is ready for rinsing, polishing, and incising. Incising for each successive color is followed by washing, polishing, and a final buffing. The shop we were at used three different techniques for applying images — painting, filling with mother-of-pearl, and pressing in cracked duck egg shells. The results were exquisite. I bought a silver-on-black painting of a fisherman in a boat pulling his net, rendered in cracked egg shells.

Our evening adventure was a rickshaw ride through town on the way to a traditional water puppet show. My driver negotiated the mayhem of cars, motorbikes, and buses as they converged at intersections, making their way through without the aid of traffic police or lights. As we sped by, I tried to photograph sidewalk vendors with goods heaped in baskets, along with billboards and advertisements in neon lights vying for attention on building facades. Shops with enticing displays of every luxury brand from Japan, Europe, and the US beckoned passers-by, while karaoke signs blinked up above.

The water puppet show was just as delightful as the one I had seen in Hà Nội during my previous trip. To the accompaniment of live traditional music and singers providing the puppets’ voices at either end of the stage, colorful puppet dragons, lions, frogs, ducks, fish, unicorns, and people performed humorous tales from folklore as they played, danced, and frolicked in and out of the water that was their stage. Standing in water, eight puppeteers in hip-length rubber boots manipulated the puppets, which were attached to long poles, from behind a screen. This form of puppetry is unique to Viet Nam and is a treat for all visitors.

Dinner after the show was at l’Etoile, a five-star French restaurant, one of many in town. The haute cuisine menu included homemade bread and butter, soup and fresh salad with pâté chaud, filet of sole, and baked banana with sherbet for dessert. Viet Nam was part of French Indochina from 1887 to 1954, which accounts for the many French restaurants.

The morning view out of my hotel room window was a spectacle of people exercising. At 5 am people were in the park, doing tai chi or aerobics. With a lively night life, which continues to all hours without the intense heat of the day, the city never seems to sleep, but pulsates 24 hours a day.

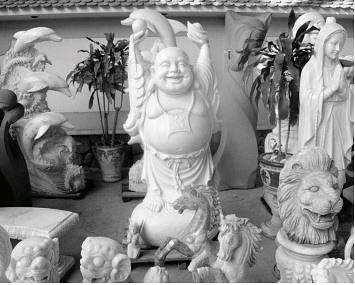

Stone carving shop

On the way out of town, we stopped at a stone carving shop, where we watched craftsmen at work. The store and its grounds displayed various statues of the Happy Buddha. Though the Communist government used to discourage the practice of religion, and 80% of Viet Nam’s population of 86 million are said to be non-believers, the culture is permeated by Buddhism, whose teachings of happiness and contentment influence daily life. 9% of the nation are practicing Buddhists.

Heading south to the Mekong Delta, we drove through the new residential areas of sprawling Hồ Chí Minh City. Million-dollar villas and giant supermarkets dotted the landscape amidst canals covered with lotuses, the national flower. Due to expanding industry in the city center and a growing population, unplanned development is transforming the surrounding landscape.

In the short span of five years between my visits, I found the vibrant Hồ Chí Minh City to have become even more furiously active and commercial. The streets are filled with new motorbikes and taxis; boulevards glitter with state-of-the-art advertising. Contemporary buildings are crowding out the characteristic older thin houses with their narrow facades and storefronts. Since urban dwellers lost everything when forced to become farmers under the Communist regime in 1975, their eventual return to the city and economic liberalization have created a new class of entrepreneurs. They and the city are definitely making up for lost time at a dizzying speed.

The Vietnamese name for the Mekong, Cửu Long, means “Nine Dragons,” as the river descending from its source high in the Tibetan plateau forms nine branches before it finally empties into the South China Sea. The vast delta, known as Viet Nam’s “rice bowl,” is shaped by alluvial deposits from the multiple arms and tributaries of the river. The fertile, heavily populated delta is connected by a network of waterways and irrigation canals. Here the dry season lasts from November to April, while the rainy season makes up the rest of the year.

High school girl in uniform

Traveling southward from Hồ Chí Minh City on a superhighway, we drove by slash-and-burn farmland, sugar cane plants, coconut palms, and banana trees. Rice fields stretched as far as the eye could see, creating a many-hued and textured patchwork punctuated with elaborate ancestral tombs. Ducks waddled in canals by farmhouses decorated with flowerpots on balconies. With intermittent views of water, we passed pedestrians in conical hats, children playing in a schoolyard, modern gas stations, and roadside cafes with hammocks for weary travelers. A mobile clothing vendor pulled his cart; motorbikes carried big loads; and high school girls in uniform long, white dresses, symbolizing purity, pedaled to school.

At a roadside stand we admired tropical fruit and discovered a specialty — fermented pork skin, made by boiling and mixing the skin with papaya and chili peppers and keeping it wrapped in banana leaves for three days. While I was not tempted to buy this specialty, I purchased peanut brittle on rice cakes and boiled peanuts in the shell, both of which made tasty snacks for the road.

Driving on a toll road, we crossed the first suspension bridge in the Delta, built by Australians. The level of the water below was low, due to China’s control of the river at the northern end. Ocean water has been seeping into the rice fields, raising concern over diminishing fresh water.

During the bus ride our Vietnamese guide, Anh, explained the country’s single-party political system. The Parliament has 500 members; elections are every four years, at which time people vote for three out of five candidates from their area. The Parliament elects the President, as well as the Prime Minister, who administers the five-year plan drawn up by the seven-member Political Bureau, the highest authority. The nation’s literacy rate is 90%; education on Communism begins in ninth grade. There is no social security or pension system. Everyone is expected to work; those who cannot are taken care of by their families. Insurance is a fairly new concept; motorbike insurance, required by the government, costs $4 annually. Big companies, including Prudential, have begun investing in Viet Nam.

Reaching the boat landing to cross the Hau River to Càn Thơ, the capital of Càn Thơ Province, we took the ferry across a busy waterway. With a population of one million, Càn Thơ is the Delta’s largest city and an important river port and commercial center. We missed seeing the Floating Market, where locals shop for a variety of fish, fruit, and vegetables by crossing from boat to boat. However, the animated Càn Thơ market was quite rewarding, with its several restaurants on the waterfront serving specialties of the region. Here we enjoyed lunch consisting of squash flower tempura, shrimp with mangoes and deseeded chili peppers, pork with mushroom sauce, and green beans with sprouts.

A walk after lunch offered a snapshot of local life. Rice, harvested three times a year, dried on bamboo mats by the roadside as farmers raked through it to speed up the process. Narrow houses with colorful, ornate facades lined the streets; stilted houses with tin roofs stood by the water’s edge; and picturesque shacks crowded the canals. Drivers transporting passengers in rickshaws pedaled up front, unlike the drivers of rear-pedaled rickshaws we had ridden in Saigon.

Altar in Cao Đài temple

Our amazing encounter of the day was a visit to a surreal temple of the Cao Đài religious sect with wildly mixed styles, colors, and designs from every Asian religion and culture. On the outside, a large eye symbolizing the religion guarded the temple entrance. The interior was a fantasyland with a blue, star-studded, vaulted ceiling and dragon-entwined pillars. The eye symbol formed the centerpiece of an ornate altar embellished with candles, flowers, and fruit behind a drawn curtain framed by a blue neon light. The light reflected on shimmering green floor tiles, divided by neat rows of bright blue cushions for seats during service.

Founded in 1926, Cao Đài is an amalgamation of preceding religions. Adherents believe in one deity, practice meditation, and are vegetarians. Their god does not appear in human form; instead, they worship a single left eye, known as Ying. There are four services a day, one every six hours, starting at 6 am. 1% of the Vietnamese population, predominantly in the south of the country, belong to the Cao Đài sect.

On the way back to the bus, we noticed young children looking out at us from behind the bars of a first-floor apartment. Going around the corner to meet them, we realized that this was a one-room preschool. The teacher asked the children to sing for us as we crowded at the doorstep. This impromptu stop delighted us all.

As we traveled to the town of Châu Đốc to spend our final night in Viet Nam, Anh spoke about his family. At the end of the war in 1975, his father, a member of the “educated elite,” was sent to reeducation camp by the Communist regime. The government took possession of everything the family owned and forced them to work as farmers, during which time they could have meat once a month. In 1982 they were allowed to return to the city, and had to begin anew by starting a home business renting out clothes for weddings. Since people were too poor to buy wedding clothes, the rental business grew quickly. Following the death of Anh’s father in 1986, the business expanded into a fully fledged wedding operation, with each family member acquiring a specialty, such as flower arrangements or hair styling. It took them three years to fully recover from poverty.

Châu Đốc is a city of 100,000 bordering Cambodia, and as such a melting pot of cultures, with ethnic Khmer, Cham, Viet, and Han Chinese people. After settling into our multistory hotel, we toured the city by bicycle rickshaw on our way to dinner with a local family. Our hosts, a family of three generations, lived in a house with a storefront, where they baked and sold “moon cakes” (consumed during the traditional mid-autumn Moon Festival). The grandmother, her tired feet soaking in a basin of hot water, minded the eight-month-old granddaughter in her lap, while the mother served us a delicious meal — spring rolls, taro soup, lotus stems, catfish, fried noodles with shrimp, and squid. For dessert we had delectable sliced mangoes.

Visiting this family reminded me of a time when a Vietnamese-American floor sander had arrived at my house in Cambridge. Upon entering my three-bedroom house, modest by American standards, he had asked how many people lived there. My answer — “Three” — had astonished him. “Only three people in this big house!” he had exclaimed. Years later it became clear why.

Châu Đốc is known for its “floating villages.” In the morning we visited one such village by boat. We cruised by the riverbanks, stacked with houses on stilts, and ambled through narrow canals lined with tropical plants. We steered by houses built on empty metal tanks or small boats, where people made a living by fishing. Large nets tied to tall bamboo sticks and metal nets under the houses were set to trap large quantities of fish. Farmed fish goes to the markets in Saigon; some is exported. Although their living conditions did not reflect it, some families are reputed to prosper in the business. As we moved through the waterways, we passed by houses with tiny balconies crowded with hanging laundry, potted plants, children, and even pets. Some had vegetable gardens right on the water. Families paddled by, waving to us.

Our captain had his wife and two children on the boat. In addition to visiting them, we met a family who lived on the river in a tiny houseboat. This family made their own fish food by mixing rice husks with vegetables, and demonstrated how tasty it was by throwing handfuls into the water as we watched droves of fish scramble for it. On the way out, walking through the tiny, neatly furnished living room, I noticed a small TV and an ancestral altar nearby. In this culture aging parents and ancestors command great respect. Bidding farewell to our gracious hosts, we returned to Châu Đốc, where we boarded a speedboat to travel into Cambodia on the Mekong River.

Reflecting on this visit to Viet Nam, I was glad to have had a second opportunity to see the country. However, if this had been my only trip, my experience would have been incomplete. For a full appreciation of the natural beauty and richness of Vietnamese culture, one must include the north, which is very different from the south.

← Laos