March 2005

My enjoyable small group travel to Egypt and Jordan encouraged me to sign up for another journey with Overseas Adventure Travel, “Inside Viet Nam,” with a post-trip to Cambodia. Many friends were surprised at this decision. “Why Viet Nam?” they inquired. What was the appeal of a country that was synonymous with war? One friend declared that the mention of Viet Nam sent chills down her back.

Fortunately these comments did not discourage me. It was worth traveling halfway around the world to meet the Vietnamese and see this country, which is no longer on the radar screen of most Americans.

My airport hopping en route to Hà Nội set the breakneck pace for the trip. The first stop of the 22-hour trip to Bangkok was Detroit which, much to my surprise, already felt like Asia. Airport signs were in both English and Japanese, there were sushi bars next to MacDonald’s, and the waiting lounge overflowed with Chinese tourists. Detroit is a hub for Northwest Airlines, a major carrier between the US and Asia. I sat near a fountain with thin arcs of water stopping in midair and then reconfiguring themselves into various patterns, as some hidden technology appeared to intercept their flow. This delightful fountain helped pass the time.

The next leg of the trip was a thirteen-hour flight to Tokyo with over 400 passengers occupying every seat, including the first class upper deck. Thanks to modern technology we had ample in-flight entertainment at our fingertips. Remote control in hand, we could call up the movies of our choice or play games on private screens. After one movie, I opted to read. Crossing the International Date Line signaled the loss of a day, which we regained on the way back.

At 6 pm the following day we arrived in Tokyo. Narita Airport was quiet and orderly as we cleared passport control and security. Instead of loudspeaker announcements, airport personnel at the gate held up signs to indicate our rows as we boarded the flight to Bangkok, a seven-hour trip. After enjoying a second dinner, which now consisted of Japanese fare, I fell asleep.

Close to midnight we reached Bangkok. A major international hub, the airport was teeming with activity. Members of our group gathered around a Thai guide waiting for us and met one another for the first time. The outdoor temperature read 37º C as we headed to our hotel for an overnight rest before continuing on to Hà Nội.

In the morning we had a delightful few hours in Bangkok. Photos of the King and Queen greeted us on all major highways. Tamarind and mango trees were everywhere. In the flower market women made jasmine garlands for weddings and offerings. Buddhist nuns in white robes stood in clusters separately from saffron-robed monks. Vendors sold freshly sliced mangoes — some of the sweetest I had ever tasted.

At noon we flew north to Hà Nội on Viet Nam Airlines. Although this was a three-hour flight, it seemed relatively short. Air hostesses in dark red traditional áo dài tunics waited on us. At the airport our trip leader, a young man named Nguyễn Dũng, welcomed us to his country. In Vietnamese the family name always precedes the given name, and “D” is pronounced as “Z.” So he suggested we simply call him “Zung,” which means “brave.” He then introduced us to our driver and his assistant. The latter plays a key role in guiding the bus driver through narrow passages or making U-turns in congested traffic.

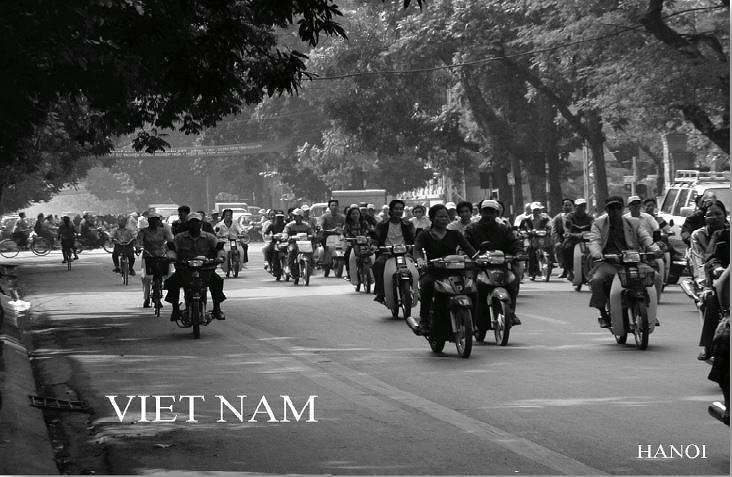

The intense motorbike traffic from all directions was an incredible entry to Hà Nội, the capital city. There were hundreds of these vehicles, which did not observe lanes or lights, and entered traffic circles honking and dodging one another to rush ahead. Cars, buses, and trucks wended their way amidst the mass of humanity on two wheels. Each motorbike was loaded with three to four passengers, often children, or cargo that varied from bananas to ducks. Nobody wore a helmet, which is only required outside the city. However, most wore masks or covered their mouths with scarves tied in back as protection from the pollution. Traffic accidents are the number-one cause of death here.

After a brief rest at our hotel, we had an orientation tour of the vicinity on foot. Zung instructed us to cross streets slowly, which would force cyclists to slow down to go around us. “Running will not slow them down, and you might get hit,” he cautioned. Crossing a street in the city is a major challenge, since no vehicle gives right of way, even at pedestrian crossings. We walked by the tree-lined Lenin Park and on the way saw many Internet cafes filled with young people. Viet Nam strives to have a high literacy rate, now at 70%. Compulsory education goes through primary school; older students have a choice between vocational training and university education. Only a small percentage of students are able to go on to higher education, because there are not enough universities to accommodate their numbers.

After Indonesia, Viet Nam is the second most populous country in Southeast Asia. One third of its 86 million people are under 35 years old. Bridal shops displaying white gowns as well as red ones, the national color, dot the commercial landscape. To provide sufficient housing for the rapidly growing population, the government divides land into narrow lots before selling it. Most new buildings are three meters wide, several stories high and ten to fifteen meters deep. They have bay windows and balconies, and are divided by a stairwell in the center. Some have storefronts on the ground floor and laundry lines on the roof, along with storage tanks, since water pressure is not sufficient to reach the top stories. These abutting town houses have painted decorative facades in shades of deep blue, green, red, and predominantly yellow, defying their uniformity in structure.

The first two of the four days we spent in Hà Nội fell on a weekend. Our tour began with a visit to Hồ Chí Minh’s Mausoleum. We drove by Embassy Row, lined with beautiful French colonial homes. These mansions, set back from the road with lush gardens, now serve foreign diplomats based in the capital city. The mausoleum is an imposing structure visible from far away. It is a weekend destination for families, including many from the provinces. There were long lines of people waiting to pay respects to “Uncle Hồ.” Making our way past school and scout groups and newlyweds, we ascended the heavily guarded mausoleum and filed by the preserved body of the nation’s leader in a glass case. We walked around the Presidential Palace Memorial site, a complex of buildings and grounds where Uncle Hồ lived and worked from 1954 until his death in 1969. These include his “House on Stilts,” a study bungalow, a fishing pond, and the mango alley of the palace where he received foreign dignitaries.

The One-Pillar Pagoda and the Temple of Literature were the other landmarks of the day’s tour. The wooden pagoda, originally built in 1049, rests on a concrete pillar rising out of a lotus pool. It was most recently reconstructed after departing French soldiers blew it up in 1954. A pagoda is a sacred place for worshiping Buddha, as opposed to a temple, where people worship ancestors or local heroes.

Built in 1070, the Temple of Literature is dedicated to Confucius. It is the site of Viet Nam’s oldest university, where scholars aspiring to be senior mandarins once studied. The large temple enclosure has five courtyards, where stone stelae inscribed with the names of scholars who passed the exams rest on the backs of tortoises. Now they are regrouped and sheltered under one roof. The French halted the exams in 1915 and destroyed the Academy by aerial bombing in 1947. The House of Ceremonies, where sacrifices were once offered in honor of Confucius, is now a performance venue for traditional music. Here we listened to a group of musicians who sang and played for us. I bought two of their CDs.

Our next adventure was a bicycle tour of the Old Quarter. This is a 600-year-old artisans’ district, with crafts and trades concentrated on 36 narrow lanes. After being silenced by the Communists for 40 years, private tradesmen have returned in the past decade, creating a commercial frenzy. From silver jewelry to gravestones, everything is here, although the specialty of each street no longer matches its name.

The day concluded with a delightful water puppet show at the Thăng Long Theatre. To the accompaniment of live traditional music, colorful puppet dragons, lions, frogs, ducks, fish, unicorns, and people performed numerous vignettes as they played, danced, and frolicked in and out of the water that was their stage. Standing in water, the national troupe of 9 puppeteers in hip-length rubber boots manipulated the puppets attached to long poles from behind a screen. This form of puppetry is unique to Viet Nam and was a new discovery for our well-traveled group of sixteen.

Water puppets

Due to the nine-to-twelve-hour time difference between US cities and Hà Nội, most of us were still on lingering jet lag on day five. Waking up at 4 am, I waited eagerly to go to the Museum of Ethnology, a showplace of Vietnamese cultural diversity. Built with the assistance of the French, this museum honors Viet Nam’s 54 ethnic groups speaking languages from five language families. 86% of people belong to the Viet ethnic group. Other major peoples are the Chinese, Hmong, and Thai. The museum grounds display houses built by village artisans from each of these diverse groups. This is a fascinating open air exhibition of rural constructions, ranging from a Bahnar communal house to a Giarai tomb. The former symbolizes male power; the latter is encircled with large wooden carvings intended to accompany the dead into the afterlife. The indoor displays are of musical instruments, spiritual objects, garments, household textiles, hats, jewelry, baskets, and other crafts.

A visit to a silk shop was our next stop, following which we returned to our hotel for some rest and to prepare for a home-hosted meal in the evening. I lay down for a short nap and woke up two hours later to a ringing telephone. It was Zung; everyone else was already in the lobby. Half asleep, I quickly got dressed, knowing I owed a big apology to the group. Within ten minutes we were on our way.

Vietnamese townhouses

Our host, an upper middle class family, lived in a multistory house that they owned. As is the custom, three generations lived here together — the parents and their two sons with their wives and children. One of the sons and his sister-in-law hosted us. He had studied law in Moscow and learned English later on. He worked for a construction company, and his brother for a business that outsourced labor. They collected fossils, some of which were displayed in wall frames, while others were free-standing sculptures that complemented the dark wood accents of the interior architecture. We had miniature sweets around the coffee table before moving into the dining room for our soup and appetizer course, followed by a customary bowl of rice with accompanying dishes of fish, pork, and vegetables. We ended the meal with fresh fruit and green tea. The three young children of the household stayed upstairs during dinner. The youngest, a baby, had a nanny. The family had no cars, but instead owned six motorbikes.

Our excursion to the village of Tho Ha was an opportunity to gain insight into rural Viet Nam. Tho Ha is 20 miles north of Hà Nội, set apart by the Như Nguyệt River. Viet Nam has 2000 rivers, which cross the country from the mountainous west to the eastern shore. A shortage of bridges contributes to traffic jams on land and increases boat traffic on the rivers. After a drive and a brief ferry ride we reached Tho Ha, known for its edible rice paper and pig farming industries. The village had a pagoda, a community house, a school, and a market, typical of all rural communities. Women sold goods at the market, while men made rice wine, trained cocks to fight, and smoked water pipes. We watched women make rice paper, chew betel nuts (an addiction that gives them black teeth), and eat fertilized duck eggs, a highly prized specialty. We walked through narrow streets, passed by pig stalls, and photographed thin round wafers of rice paper drying on bamboo lattice frames against the roof tiles of mud brick houses. As we waved goodbye to happy children on the riverbank, strewn with plastic bags, I admired their resilience.

A highlight of our trip was the history lecture by Hữu Ngọc, a writer, journalist, translator, and cultural researcher. He compared Viet Nam to a 3000-year-old tree that had survived the crushing storms of the Chinese, French, Japanese, Cambodians, and Americans. Each storm had left its physical and cultural detritus, thus prompting the Vietnamese to make independence a priority at all costs. According to Mr. Hữu, if the French had stayed away after World War II, as they had promised, Viet Nam would be a capitalist country today. Fueled by the Allies’ victory over Japan, France returned to its rich colony in 1948, forcing Hồ Chí Minh to seek help from Moscow and Beijing to advance his “nationalist strategy.” This aid came at the high cost of the Communist ideology that split up North and South Viet Nam, resulting in the National War of Independence and the American intervention. What led Hồ Chí Minh into war was the ideal of independence and national unity, rather than of class struggle or reform. He did not live long enough to see the country’s liberation and unification in 1975.

After the end of the “American War,” as it is called in Viet Nam, the nation had to catch up economically to its neighboring countries, while suffering famine and facing another foreign invasion, from the Khmer Rouge in 1976. Collective farms appeared everywhere, educated people were sent to “reeducation camps,” and many left the country for the US, Australia, or Europe. In 1986 a policy of “renovation” brought economic reforms that moved the country from starvation to sufficient abundance to export rice. A successful market economy introduced competition and allowed the private sector to operate within the Communist system. Today’s “open door” policy brings 3 million tourists a year and encourages foreign joint venture investment.

The lecture concluded with an emphasis on striking the right balance between economics and cultural identity, which was destroyed, in our speaker’s opinion, by western individualism. He hoped for a strong society with equity and prosperity underpinned by enough food, health care, and education for all. He proudly pointed out that Vietnamese culture was not Communist or Marxist, but national. Viet Nam had a rice-based civilization symbolized by the bronze drum and dating back to 1000 BC. Enlightened by this most informative lecture, many of us purchased Mr. Hữu’s 1100-page book, Wandering through Vietnamese Culture. Upon my request for a signed copy, he went to his office to bring his special pen.

The Hỏa Lò Prison, nicknamed the “Hanoi Hilton” by American POWs held here during the war, was a stark reminder of the horrors of incarceration. Built by the French in the 1890s to contain anticolonial movements, its one remaining building, the Maison Centrale, has been preserved as a museum. The Memorial Courtyard honors patriotic combatants, depicting carved images in chains and handcuffs; the interior cells display various forms of torture instruments. The prison’s former inmates include Douglas Peterson, the first US ambassador to the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, and Senator John McCain. There is also a monument commemorating McCain, erected by the lake where his aircraft was shot down.

Our final activity in Hà Nội was a demonstration of Vietnamese cooking. The instructor showed us how to make spring rolls and caramelized fish in a clay pot. I volunteered for the spring rolls, as my fingers were adept at stuffing and rolling from preparing Turkish food. Afterwards we enjoyed these dishes for lunch and picked up the recipes to try them at home. Ginger and lemongrass are predominant flavors in Vietnamese cuisine. I brought back a small bag of each.

Our next journey was overland to Hạ Long Bay, 120 miles due east of Hà Nội. Known as the “Emerald Bay of Viet Nam,” it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Due to rough road conditions, the slow half-day journey allowed us to view the picturesque countryside. Lush green rice fields dotted the flat landscape. Women in conical hats scooped water from a canal to flood the fields; others stooped in knee-deep mud to weed them. Water buffalo worked the land.

Earthen tombs in family plots clustered around small temples with red tile roofs in the rice fields. After death farmers bury the deceased, followed by cremation and reburial three years later. The bones are washed in perfumed water and collected in a small ceramic coffin. So there are two burial ceremonies. This is a culture that respects old age; burial ceremonies are more common than birthday celebrations. Naming children after elders is considered disrespectful.

As we drove along, agricultural landscape gave way to industrial. The Gulf of Tonkin across from Hạ Long Bay provides 90% of Viet Nam’s coal. We passed by small towns where thousands earned a living working in coal mines. The sidewalks were powdered with coal dust as trucks in front of depots loaded up. Hard coal is used for power plants, soft coal for fuel and, mixed with mud, for cooking. A mixture of lime and coal ash produces cheap bricks, allowed for use in buildings of up to two stories. The towns also had factories, where cheap labor was used to produce high-quality goods for export, such as textiles for Pierre Cardin or shoes for Nike. The biggest export market is Japan; most laborers go to Korea, Malaysia, or Taiwan.

Hạ Long Bay is a resort town with many new hotels in anticipation of the growing tourist industry. However, prices are still quite modest. On the streets young girls sell T-shirts at $2 apiece. At a silk shop across from our hotel, I bought a reversible two-color tufted silk jacket for $50. A similar one in Hà Nội was priced at $100. The local market was a cacophony of sounds, sights, and exotic fragrances; we walked through stalls packed with mounds of produce, lichee nuts, bananas, star fruit, dry fish and seafood, tall burlap bags full of assorted offerings, spices, and stacks of rice products.

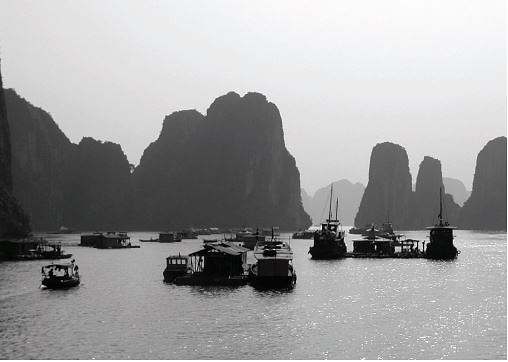

Hạ Long Bay

Cruising Hạ Long Bay was magical. The name means “dragon descending.” According to legend, a dragon spewed pearls out of its mouth, dotting the bay with over 3000 limestone islands. They appeared in the mist from a distance as a chain in silhouette, jutting from the sea like gigantic rock sculptures as we drew near. Wooden junks in full sail and oar-propelled sampan fishing boats gliding on the bay complemented the tranquil beauty. We weighed anchor at an island pierced with grottoes which bore an uncanny resemblance to animal shapes, walked by mangroves, and looked at pearls fished in the bay. We lunched on fresh seafood prepared on board by the crew, and visited a fishermen’s hut where three generations lived year-round from the water, farming prawns, shrimp, and king crabs.

To fly to Huế on the central coast of Viet Nam, we had to backtrack towards Hà Nội. It was raining; we passed two trucks that had collided, sending one off the road. Traffic accidents are often settled between drivers, because involving the police requires large bribes. Police and military officers receive relatively high pay; yet they are not able to travel outside the country. As we approached Hà Nội, we noticed a procession of people with headbands. It was a funeral led by a drum and a band; these were followed by an ancestral altar, the coffin, and people walking their motorbikes. The line-up went from elders to children — family members in white headbands, others in yellow, and children in red. Burial days are chosen by consulting Chinese books. Professional mourners help out.

Huế, as the imperial capital, has been a main cultural, educational, and religious center. However, it is an economically less developed city, with a pace of life slower than in the north. Outside the city is a former US military base with concrete bunkers, which now belong to the Vietnamese. Our adventures here started with a dragon boat cruise on the Perfume River, which mingles with scents of flowers along its way. Workers were busy dredging up sand from the river to sell; to carry the sand to construction sites, they loaded heavy cargo boats made of scrap metal from US warplanes.

First we visited the Thiên Mụ Pagoda, a center for Buddhist protesters during the American War. Banging the bronze gong attracted the Buddha’s attention, while burning incense sticks carried prayers to the heavens. Here orphan children received training to become monks. The old section of town, surrounded by a moat, is a walled citadel with eleven stone gates; the Forbidden Purple City within the Imperial Enclosure was a private area reserved for the Emperor. Nuns served us lunch at the Đông Thuyền Pagoda. The vegetarian meal included lentil soup, spring rolls, fried mushrooms, sautéed tofu, sweet potato leaves, and bananas for dessert. The Minh Tu Orphanage was home to 195 children from two months to eighteen years of age. The children slept on hardwood beds and ate meals prepared by a volunteer cook. They learned furniture making when not in school. For sale were beautiful pieces made of almond and jackfruit wood.

The highlight in Huế was a visit to the home of Mr. Phan Thuận An. A former university professor married to a descendant of the royal family, Mr. Phan gave us a tour of his house and garden. Designed on the principles of yin and yang, everything in the lakeside complex was in absolute harmony. Having authored six books here, our host, a historian, had drawn much inspiration from his surroundings. Across from the main door was a stone spirit house, which distracted bad spirits from entering. We had to walk around it to reach the door. Following dinner, which included cooked figs and pressed salad, we enjoyed a tour of the ancestral altars and royal heirlooms.

Our departure day from Huế coincided with the 30th anniversary of its liberation. Street floats carried portraits of Hồ Chí Minh; dragon boats raced on the Perfume River. Eight teams competed, each representing a commune of 200-500 houses. Spectators arrived in open trucks or on foot. Men and women were in traditional dress; young people in blue jeans stood out in their red caps, each with a yellow star. On Liberation Day school children go on field trips and adults to psychics in search of their war dead.

Overland we headed south to Đa Nẵng on our way to Hội An. We traveled on National Highway One, which goes from Hà Nội to Hồ Chí Minh City, paralleling the railroad — a 29‑hour train ride between the two cities. The Liberation Day celebrations traveled south with us, as all the towns along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail were freed within days of one another. Every little shack amidst plastic trash flew the Vietnamese flag in anticipation of the big day. There was a cemetery for soldiers in every village. As our van climbed 100 meters above sea level, we passed crowded buses with chickens and bicycles strapped on top, and loaded trucks stopping to cool off their engines before they could continue; a tunnel through the mountain was under construction. Since this is the only road connecting north to south, it provided strategic checkpoints for the French and Americans during the war, as was evident from the many bunkers.

Once we crossed over the mountain driving through the clouds, the cool, drizzly weather of the north gave way to sun. We turned off the highway to reach Đa Nẵng, and stopped at the Lăng Cô Beach Resort long enough for a glimpse of the China Sea. Men in boats lowered nets to the bottom of the sea and scared fish into them with a stick. They did this from round bamboo boats, rather than long sampans, which are not as safe on open seas. We visited a marble factory near a quarry, and watched craftsmen chisel dragons out of stone.

Hội An, a well preserved ancient port town, has a Japanese covered bridge with its own temple and statuary as a landmark. Traditional houses with brick exteriors and wooden interiors line the narrow streets of the old quarter. A week-long festival, the Heritage Journey, celebrating the 30th anniversary of Liberation, was in full gear. Banners stretched across the streets, where decorative stars alternated with hammer and sickle symbols made of lights. Cemeteries honored the dead with signs that read “The country will remember your contributions,” as bicycles adorned with flags transported veterans for visits. People flocked to boat races, folk dances, and street fashion shows of contemporary designs inspired by tradition. Colorful lanterns everywhere enhanced the nightscape.

The Pacific Hotel had delicious doughnuts among its breakfast offerings. Homesick for American food, the group fortified itself on doughnuts before departing for Mỹ Sơn, the capital of the Champa Kingdom. The Champa were Hindus who came north from Indonesia and Malaysia. The Kingdom prospered from the 2nd to the 15th century. To get to this isolated valley, we first traveled through countryside of rice and tobacco fields by van, and then transferred to jeeps.

Recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1999, Mỹ Sơn, the holy land of the Champa, has ruins of many red brick temples. American bombs dropped on the resistance fighters, who used the area as a hiding place, have destroyed 45 of the temples. On the remaining ones, elaborate Hindu carvings are visible in varying degrees through the moss that has crept over them. We met school children who were on site drawing copies of the bas-reliefs. Stubby growth covered the surrounding hillside, which had been denuded by sprayings of Agent Orange.

On the way back we visited a house, where many generations passed on the 400-year-old craft of bronze gong making. One family member melted down the bronze in an earthenware pot over a charcoal fire, while another prepared a clay mold by tightening its two halves with bamboo ties. They then poured the molten bronze down a hole in the center of the mold, and took it out when it cooled off. Polishing and tuning by beating completed the production process, which they repeated to make ten gongs a day.

Early the next morning we left for Đa Nẵng airport to catch a flight to Hồ Chí Minh City, our final destination. By 6 am the road was already clogged with buses, cars, trucks, and motorbikes loaded with bananas, scallions, gourds, and a panoply of other produce on the way to the market; some even carried freshly killed pigs. Farmers were in the fields; children headed for school. The Vietnamese are hard-working people; due to their work ethic and lean diet, one problem they do not have is obesity.

Hồ Chí Minh City, the former Saigon, is an international port with a population of 8 million people, double that of Hà Nội. It is a bustling, sprawling city that is hot and steamy year round. “Sài Gòn” means “land of the gon tree.” Vietnamese, like Chinese, is made up of single syllables, each of which has a meaning. The government forbids using only English names on stores; signs appear in large Vietnamese letters, followed on a second line by English translations much smaller in size, although Kentucky Fried Chicken has a surprising presence in the city. The stream of motorbikes carries a spectacle of people in conical hats, caps, helmets, and scarves; high school girls in white áo dàis; and women in long gloves and fashionable face covers for sun protection.

Street vendor

Half of the one million Chinese in Viet Nam live in Saigon, the center city still called by that name. Our city tour began in the Chinese market, the biggest in the city. It was an incredible sensory experience. Women vendors sitting in hammocks and surrounded by bags of goods sipped chrysanthemum tea to keep cool and fanned themselves in tiny stalls. Aromas of dried strings of papaya and coconut mixed with those of dried fish. Mounds of mangoes, jackfruit, durian, and longan fruit vied for attention as shoppers tried to make their way through the narrow lanes.

Our hotel was around the corner from the Opera House, a legacy of the French Colonial period, along with other buildings lining Saigon’s boulevards. New hotels, such as the Novotel, Sheraton, and Hyatt, dot the skyline. Jewelry stores and boutiques glitter into the night. However, the maddening intensity of motorbikes heeding no traffic regulations discouraged me from pedestrian activity. Our restaurant experience in this cosmopolitan city ranged from pizza at an Australian restaurant to fine French dining.

A visit to a lacquerware workshop helped me to understand this complex and time-consuming craft. The process of making an object begins by splitting and coiling bamboo into a traditional shape, which is then coated with a paste of lacquer, made by sap collected from a tree indigenous to Southeast Asia. Then the object is cured for a week in a dark, humid room. After several lacquer coats, alternating with week-long cures, the object is ready for rinsing, polishing, and incising. Washing, polishing, and a final buffing follow successive incising for each color. The results are exquisite.

On the way to the Củ Chi Tunnels, we stopped by a rubber tree forest. These trees, planted in neat rows, have a life span of 40 years. Just before the rainy season, the bark is scored for the sap to drain into clay pots tied to the trees. Several times a day the pots are emptied and the rubber taken to the latex factory to be manufactured into tires, mattresses, etc. Rubber is Viet Nam’s second largest export item after rice, followed by coffee. Another discovery was a grove of cashew trees with fruit that looked like small red apples. The cashew nut is on the outside of the fruit by the stem. Each piece of fruit bears one nut.

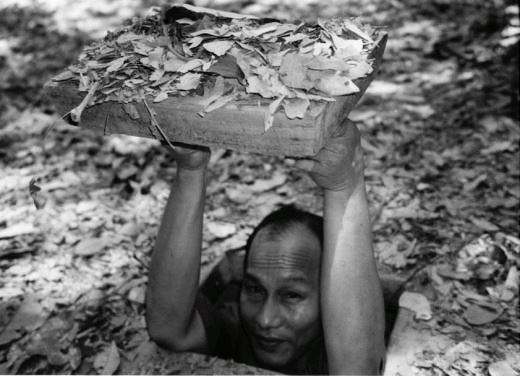

Entrance to narrow tunnel

The eye-opener of the trip was a visit to the Củ Chi Tunnels, a 75-mile-long underground maze where thousands of fighters and villagers hid while at war with the Americans. The Viet Cong built and expanded this vast network over 25 years. We went down through a narrow opening enlarged for tourists, where we saw an operating room with its crude instruments, a meeting room, a mess hall, and a kitchen. Smoke from the kitchen was deflected into bamboo chimneys that doubled as traps, causing victims to fall in when pulled. The tunnels narrowed at the center, to capture Americans in case they were successful in entering. The Viet Cong’s small lithe frames as opposed to the Americans’ big stature played an important role in such strategic planning. Women worked in the tunnels during the day and in the rice fields at night in order to feed the soldiers, dipping rice rolls into crushed peanuts to provide them with protein. While we were in Hồ Chí Minh City, nearly 200 of these heroic mothers from 33 cities gathered at the Palace of Unification to celebrate the 30th anniversary of their victory.

Our journey the next day was to the Mekong Delta. We traveled 70 kilometers south of Saigon on the National Highway to Mỹ Tho, which lies on the left bank of the northernmost branch of the Mekong River. We drove by slash-and-burn farmland, “scare-ducks” (there are no crows in Viet Nam), coconut palms, lots of plastic trash, monuments to soldiers, and roadside cafes with a hammock by each outdoor table for weary travelers. At the pier we boarded a motorized boat to enjoy the view of the river banks as we sipped fresh juice from coconuts with straws. Shacks on stilts lined the banks of the river, and laundry washed in its brown waters hung from tiny balconies. Young boys waved to us as they swam in front of their slum houses. Cargo barges hauled fruit to the market; ferries shuttled passengers to and fro.

To reach one of the islands on the Delta, we transferred to paddleboats and cruised through narrow canals lined with lush tropical plants, including water coconuts. In the canals, nets tied to tall bamboo sticks trapped fish. Upon reaching land, we rode carriages drawn by donkey-size horses to a candy factory. Workmen drained coconuts of their juice, ground their meat, and cooked them over a hot oven fueled with the shells. Pots equipped to stir the liquid candy automatically mixed in the various flavors. Once the candy jelled, young girls cut it into small pieces and wrapped it in edible rice paper at incredible speed, as they were paid by the number of pieces wrapped.

Lunch was at a garden restaurant. The spread included fresh spring rolls, grilled “elephant ear fish,” giant shrimp, noodles wrapped in rice paper, sliced cucumber, assorted meats, and vegetables served over steamed rice. We moved to a different table to enjoy a plate of fresh banana, pineapple, and papaya for dessert. We sipped green tea flavored with kumquat juice, while local folk musicians treated us to vocal and instrumental music.

On our final half-day in Hồ Chí Minh City we toured the War Remnants Museum. Though the war ended 30 years ago, the sorrow has not gone away. Remnants of assorted bombs and planes used by the Americans are on exhibit on the museum grounds. The indoor displays are of photographs and journals depicting both of the warring sides. Factual information reminds visitors that 3 million Vietnamese were killed, 4 million Vietnamese were injured, and over 58,000 American army men died in the war. By the time I came out of the museum, I had a big lump in my throat and knots in my stomach. All I could do was walk over to the donation box and drop in all my Vietnamese money to help the war victims.

As we departed for the airport for our flight to Siem Reap, I felt tired but happy that I had made this trip. It had helped me separate Viet Nam as a war from Viet Nam as a country. I felt grateful for the graciousness the Vietnamese had extended to us. Although their character had been shaped by war, they exuded acceptance and peace. I will forget neither the woman who gave me her place at the hotel spa in Hội An when I wanted an appointment and they were fully booked, nor the two hard-working girls who gave me a full body massage for $12. The former said, “You are a guest in our country,” and the latter declared, “America very big country, very famous,” as they broke into smiles.

Viet Nam is going through an enormous transition. As it comes to grips with its past, it is determined to make it. And it will.

Boat transporting produce

← Bahamas