WESTERN TURKEY

The town of Marmaris lies on a large bay encircled by pine-covered hills. A passageway from the Mediterranean to the Aegean Sea, it is one of Turkey’s famed resorts. Successor to the ancient fortified Carian city of Physkos, first built in 3000 BC, Marmaris became an Ottoman town in 1390 and part of the Turkish Republic with the withdrawal of French forces in 1914. A narrow road with steps leads up to the fortress, which houses the Archeological Museum with its ethnographic division. The museum’s collections consist of Hellenic, Roman, and Byzantine marble statues, as well as ceramic and glass artifacts found during excavations in the region.

Driving north from Marmaris we reached the town of Çine, where we had lunch. Every place in Turkey seems to have a local specialty; in Çine it was meatballs, which were delicious. Near the town of Selçuk, we drove up Ayasuluk hill to see the 6th-century Basilica of Saint John the Theologian. Built by Emperor Justinian and restored by Turkish and American archeologists, the cathedral is based on the plans of Justinian’s long-vanished church in Constantinople, which was also the archetype for the Basilica of San Marco in Venice. Built on a hillside, the basilica — with its brick arches and blue-veined marble columns, some bearing the imperial monogram of Justinian and his empress Theodora — holds the grave of Saint John the Theologian.

Our day ended at the Kısmet Hotel, located on a promontory by the Aegean in the town of Kuşadası and eighteen kilometers away from Ephesus, the site for our excursion the next day. This hotel, my favorite in the region, has beautiful gardens, a beach, and splendid water views. My best friend from high school, Ülkü, who lives in Izmir, joined us for the final day of our tour, staying with us at the hotel. We enjoyed dinner at the outdoor restaurant overlooking the marina.

Ephesus was one of twelve Ionian cities founded in the 11th century BC. It changed rulers many times, becoming a major port for trade across Asia Minor during the time of Persian King Darius (521- 486 BC), who built a highway, the Royal Road, linking his capital at Susa to Ephesus. In 333 BC Alexander the Great brought Ephesus under Greek domination, which lasted until the beginning of Roman rule in 189 BC. The city continued to flourish.

During the latter half of the 1st century AD, Ephesus became a center for the new Christian faith. Saint Paul established a community of both Jewish and Greek converts here. It was in Ephesus that Theodosius II later convened the Third Ecumenical Council, which decreed that Christ was both human and divine, and that Mary was the Mother of God. The city declined under the Byzantine Empire; the harbor silted up and the city was abandoned in the 14th century.

Excavations begun in 1863 uncovered the site of the Greek Temple of Artemis. From the foundations of the temple, archeologists believe that it was erected on the site of the ancient sanctuary of Cybele, the Anatolian fertility goddess, predating the Ionian Greeks. Rebuilt during Alexander’s time, the temple’s size and magnificence earned it a place among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World (alongside the Pyramids of Egypt, the Colossus of Rhodes, the statue of Zeus at Olympia, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Lighthouse at Alexandria, and the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus). After its final destruction, the temple was used as a quarry for the church of Saint John. Today all that remains of the temple is a single column.

The archeological zone of Greco-Roman Ephesus requires time and stamina. We started at the Embolos or Colonnaded Way, and walked downhill, turning into side streets to see monuments. The Odeon was a small theater; built as a council chamber, it also functioned as a concert hall. The semicircular auditorium with tiered seats and radial stairways provided a good setting for a group photo. The Temple of Hadrian was an attractive structure, with columns surmounted by semicircular arching friezes and a keystone carved in relief with the bust of Tyche, goddess of good fortune. Other well preserved structures include the Nymphaeum (monumental fountain) of Trajan, a relief of the goddess Nike, public latrines, and baths.

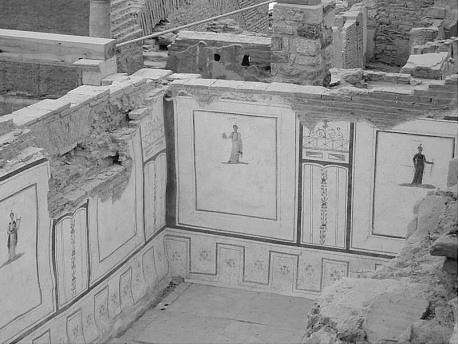

Terrace Houses at Ephesus

Across the street from the Temple of Hadrian is one of the latest excavations at Ephesus, which has unearthed a residential quarter from the late Roman period on the lower slopes of Mount Coressus, along with a row of shops in front. The inhabitants of this quarter were the wealthiest in Ephesus, as evidenced by their luxurious dwellings, comprised of rooms around a columned enclosure. Some of the villas still retain their marble and mosaic pavements, along with original wall frescoes. They are called the Terrace Houses, because they are built on tiers rising up the slope, so that the roof of one house serves as the terrace of the one above. Separate admission is required to see this quarter.

The Colonnaded Way descends to the splendidly restored Library of Celsus. This edifice was founded in 110 AD by Consul Julius as a funerary monument to his father, Celsus, who had been a Roman senator and proconsul of the province of Asia. The library stands over vaulted substructures on a podium at the western end of a marble courtyard, approached by a flight of nine steps. The facade is divided in front into two stories, each with eight Corinthian columns arrayed in pairs. Between the lower pairs of columns are niches with statues of female figures personifying the virtues of Celsus and identified by inscriptions as Wisdom, Valor, Thought, and Knowledge. The interior of the library stored some 12,000 books in cupboards and on shelves. After serving the cultural life of the community for 145 years, the library was burned by invading Goths in 262 AD.

The Ephesus Theater is the largest in Asia Minor, with a seating capacity of 24,000. It dates from the early Hellenistic period, with additions from the Roman era. In Hellenistic times, actors performed on a raised stage, the Proscenium, which was erected in front of the stage building. The Romans erected a monumental stage building to include the Hellenistic theater.

Alongside ordinary theatrical performances, the Ephesus Theater was also the focal point of an annual mid-winter festival celebrating the birth of Artemis. The idol of Artemis was carried in processions from the temple to the theater and back. The cult of Artemis was supplanted by Christianity as it took root in Ephesus. Saint John the Theologian is said to have converted a great assemblage of Ephesians, who had been summoned to the theater by the Roman governor of the city.

The Marble Way is one of the main streets, beginning below the theater and running southward into the center of the city. The street takes its name from its marble pavement, which was laid in the 5th century AD. It was designed as a thoroughfare for wheeled vehicles, with pedestrians using a raised walkway. A crude carving on the pavement — showing a woman’s head, a triangle, and a foot, indicating the direction to a brothel — points to the southern end of the Marble Way.

Our attention exhausted after four hours of walking around this ancient spectacle, we were ready for lunch. We drove to Şirince, a quaint small town known for its restaurants featuring local home-cooked food. Near Selçuk, Şirince is a former Greek town nestled in the mountains, with red tiled roofs and whitewashed houses. Here we enjoyed specialties of the Aegean region — stuffed zucchini flowers, ground lamb wrapped in fresh grape leaves and served with yogurt, purslane salad with garlic yogurt, and other dishes featuring local mountain herbs. Even the cherries we enjoyed came from the owner’s garden. Afterwards, we walked downhill on narrow cobblestone roads, going in and out of small shops selling local crafts.

The final highlight of our day was the Selçuk Museum. Exhibits here are grouped in a series of six galleries — objects found during excavation of the Terrace Houses; statues from Roman nymphaea in Ephesus; marble theatrical masks and Byzantine crosses; funerary relics, portrait busts, and original reliefs from the Temple of Hadrian and the Hall of Artemis; two large statues of Artemis; as well as dedicatory offerings found in the temple and dating from the 8th century BC. Both statues of Artemis represent the goddess with many breasts. The cluster of large nodules she wears above her waist is thought to be bull testicles, symbolic of her role as a fertility deity. Among other striking objects were a marble head of Socrates and a marble statue known as the Resting Warrior. The garden has sarcophagi, temple fragments, and fountain statues.

Reluctantly, we returned to Kuşadası to prepare for an early departure the next morning. Ülkü and I walked to the harbor to watch cruise ships over a cup of tea. The boardwalk was teeming with young people in trendy outfits. There was not a headscarf in sight. In Turkey there is a saying that “If you ever get bored in Istanbul, just go to Izmir.” The validity of this saying extends to Kuşadası, the tourist haven of the region.

Kuşadası

Nedime, our guide, had arranged for a spectacular farewell dinner at the hotel, where our table had a view of the marina. Seated at individually candlelit place settings, we watched the sun go down. The waiters arrived, carrying dishes covered with copper domes, and added to the spectacle of the evening by lifting all of the domes on cue.

Ending our tour in western Turkey was the perfect finale to what participants described as their most enjoyable trip ever. It was the culmination of a truly remarkable adventure, which had often taken us off the beaten path. Physically exercised, intellectually stimulated, and with our taste buds sharpened, we returned home, our bags bulging with souvenirs.