CENTRAL ANATOLIA

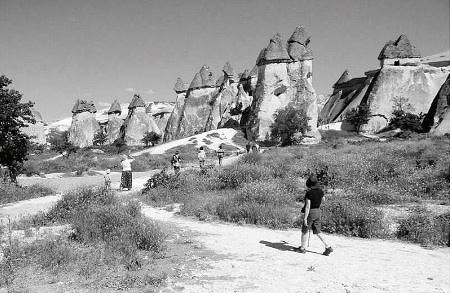

Cappadocia landscape

Cappadocia, which derives its name from the Hittite word katpatuka, meaning “land of beautiful horses,” is a haunting, almost imaginary land southeast of Ankara in central Anatolia. 1000 meters above sea level, the terrain is a nature-made fantasy of white soft rock called “tufa,” shaped over time into starkly dramatic forms from the hardened lava of nearby Mount Erciyes. Frescoed churches and labyrinthine underground cities, carved from soft volcanic stone, enhance the indelible impression of the area, which has a continental climate of hot days and cold nights.

The closest airport to Cappadocia is in Nevşehir, where we flew from Istanbul. On the way to our hotel near Üçhisar we stopped in the village of İlicek to have lunch with a local family. The residents of this village are Shiite Alaouites, who believe that Ali was a divinely ordained caliph. Their practices set them apart from the Turkish Sunni majority. Although 10 million of Turkey’s population of 70 million are Alaouite, I had not met any members of this sect, and welcomed the visit.

Our host family consisted of a husband, a wife, two children, and a grandchild. The muhtar, the elected head of the village, joined us for lunch. The dining room featured photographs of Imam Ali and Atatürk, hanging side by side. In 1925, shortly after the founding of the Turkish Republic, all religious orders were outlawed; however, some of Atatürk’s reforms can probably be traced to the influence of worldly-minded Alaouites, who observe a tolerant form of Islam. They consider men and women equals, do not favor headscarves, and pray in a community house, called Cemevi, instead of a mosque. Their prayers are in Turkish, not Arabic, and are accompanied by stringed instruments.

Over a plentiful lunch of soup, meatballs, chicken with pilaf, salad, and two types of dessert — sütlaç (rice pudding) and tulumba tatlısı (a dough-based sweet) — we exchanged personal information. Our hostess was one of thirteen children in her family and had come to the village as a bride from the nearby town of Hacibektaş, the center of the Bektaşi dervish order. She and her husband were happy to have only two children. They admired our ability to travel long distances to meet others. The muhtar had grown up as one of nine children and seemed proud to be the elected head of his village. He defined his job as being a bridge between the villagers and the state.

Kaymaklı, one of 36 underground cities discovered so far, was our next stop. Burrowed into the soft rock by Hittites as a place of refuge from invaders, the city housed up to several thousand people at a time. Stooping to pass through tunnels connecting open areas, we descended several stories. Through sloping passageways between communal kitchens and living spaces, we explored some of the cave-like rooms, which keep an even temperature throughout the year and are all well ventilated by hidden air shafts. Following this remarkable visit we called it a day.

Balloons over Cappadocia

The next morning three of us got up at 4:45 for an optional hot air balloon ride over Cappadocia. Dressed in many layers for the chilly air, we left for the balloon field at 5:10. As colorful balloons prepared for the flight, we had a boost of tea and cookies. Our pilot, Seyhan, gave us instructions for take-off and landing after we filed into the balloon basket — sixteen people, four per section. We floated over the countryside, shaped by rock canyons and freestanding rhythmic tufa formations, as fertile valleys, fruit orchards, houses, roads, and streams rotated below us. A pack of wild dogs cut through the fields, Mount Erciyes peeked through the clouds, and the rooftops of the town of Ürgüp glowed in the morning sun. At a distance, other balloons looked like multicolored giant tops suspended in mid-air. Our tranquil hour-long panoramic journey ended with champagne mixed with sour cherry juice, courtesy of the balloon company, to celebrate our perfect landing.

Following a lavish buffet breakfast back at the hotel, we embarked on a two-hour walk around the town of Üçhisar. With its prominent natural citadel as a backdrop, we followed a rural road flanked by multicolored wild flowers. Farmers worked in fertile fields of wheat and barley, nourished by volcanic ash. Odd, conical forms of tufa limestone, with colors varying from white to gray according to the eruptions which had created them, adorned the landscape, with an occasional burst of greenery or flowers. In the town of Ortahisar old cave houses stood stacked next to new stone ones, built right into the rock. Arbors and house plants in tall empty cans added to the rural charm.

The biblical realm of Cappadocia is preserved in the Göreme Open Air Museum, a volcanic valley filled with monastic rock churches. Built in spaces hollowed from the soft tufa and once used for pagan worship, these churches were mostly built to shelter Anatolia’s early Christians from Roman persecution; some date from the 3rd century AD. Over 3,500 rock churches have been identified in the area. A number of symbols, such as animals, plants, and crosses, appear throughout the interiors; the narrative frescoes date from the 10th and 11th centuries.

Carpet weavers

Rug weaving is a time-honored craft in central Anatolia; cooperatives hire women to keep it alive. Our visit to a workshop called Sentez Halı took us through all the stages of making rugs, from silkworm cultivation to spinning, dying, traditional patterns, and weaving techniques. Silk filaments are pulled from cocoons, which have been softened in hot water. Natural dyes, which can produce irregular results, are used for wool rugs, as opposed to chemical dyes for silk, which requires an even surface. The quality of a rug is determined by the density of knots tied; double-knotted rugs with up to 800 knots per square inch command the highest value. Following a commendable presentation and a superb display of the variety of Anatolian rugs, few of us could resist the temptation to purchase one.

The town of Avanos is known for its pottery and its kebab cooked in red clay pots. We tried this specialty for lunch at a restaurant called Sofra, which means “table set for a meal.” Cooked in individual pots sealed with dough, kebab is served after the neck of a pot is broken open by an expert waiter with the blow of a knife. Then chunks of mutton cooked with vegetables are poured onto serving plates. This novelty was enjoyed by all.

Our visit to a ceramic workshop, called Galip’s House, was another learning opportunity. A fifth-generation potter, Galip still uses a kick wheel, a tool introduced by the Hittites in around 2000 BC. As we watched, he made a teapot, carefully attaching the spout at an angle. Hand-painted pottery inspired by Hittite designs was especially beautiful.

After three nights in Cappadocia, we headed south toward Beyşehir, stopping along the way to break up the long ride. The first leg of the trip took us to the Konya Plain on the old Silk Road. We stopped at the 12th-century Sultan Han caravanserai, a distinctive example of Seljuk architecture featuring a stone doorway deeply carved with geometric patterns and inscriptions. These inns with courtyards were built 20 miles apart, a day’s trip on camel or horseback. They lost prominence with the discovery of sea routes.

Crossing open farmland for three hours, we reached Sille, a small town within Konya province. We stopped for lunch at a restaurant which was on the ground floor of a historic house with beautiful wooden beams. The owner, who was also the cook, served us a delicious six-course meal. A walk about town afterwards included two points of interest — a candle factory and an old Greek Orthodox Church with carved imagery on its stone facade. In the former we saw various wax molds, and wicks being attached to candles; in the latter, which had been neglected since the population exchange with Greece, the sadly fading frescoes and dome imagery of a once beautiful church begged to be restored.

Mevlana Museum in Konya

The next point of interest was Konya, the Roman city of Iconium, and capital of the Seljuk Empire for over 100 years starting in the late 12th century. The city is renowned today because of its association with Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi and the Mevlevi Dervishes. Their tekke (lodge) and museum are the focus of the city, where Rumi, a mystic, poet, and philosopher, lived from 1227 to 1273. He welcomed everyone, regardless of creed, ethnicity, social status, or past behavior. The order of his followers, known in the West as the “Whirling Dervishes,” was founded after his death by his son, Sultan Veled. It was abolished in 1925; the lodge and Mevlana’s tomb were turned into a museum, which is distinguished by its fluted turquoise tower. Now the date of Mevlana’s death, December 17, is commemorated annually in Konya with a week-long celebration. We walked around the museum complex along with many others, including recent college graduates, who had come to visit the tomb with their families.

Our destination for the night was the town of Beyşehir, where we visited another Seljuk masterpiece, the Eşrefoğlu Mosque, built from 1296 to 1299. Situated on Lake Beyşehir, the mosque is a jewel of wooden architecture; it has structural cedar posts with carved and painted ebony capitals. In the center is a large square hole, which collects water from the roof to keep the wooden posts from drying out; the water also serves as a means of cooling in the summer. A decorative carved fence separates the water storage section from the surrounding carpeted areas reserved for prayer. Ceramic tiles with geometric patterns contribute to the rich look of the interior. The imam, winner of competitions for his chanting, recited a short segment from the Koran for us.

Kuşluca, a small village near Lake Beyşehir, is where we spent the night with a local family. On our way Nedime had another discovery for us — a Hittite sculpture, supposedly the world’s oldest, in the town of Yalvaç. Three partially carved sheep, attached to a stone slab near a stream with ducks, watched the surrounding farmlands.

Our hosts, who lived nearby, introduced us to local life in two neighboring homes. Half of our group of sixteen spent the night in the mother’s house; the other half were guests of her son and his wife. The family were farmers and herders with multi-story rustic homes, where we slept in twos and shared bathrooms. The two groups joined for dinner and breakfast at the mother’s house. Early in the morning we watched the cows being milked. At breakfast we enjoyed spirited conversation, in addition to local specialties; the big hit was hashish paste, made with opium seeds and tahini and spread on bread with honey. These seeds came from a family plot of white poppies.

Poppy fields near Kuşluca

Charmed by our village visit, yet ready for the Mediterranean sunshine, we continued our journey south.