ANTALYA AND THE “BLUE VOYAGE”

FETHİYE TO MARMARİS

As we headed south from Beyşehir, a chance to visit an elementary school, as well as the weekly market in Eğridir, gave us further insight into the lives of local people. The school, which catered to the children of farmers and herders in Budak, a small village near Lake Beyşehir, surpassed our modest expectations. Besides the customary bust of Atatürk outside and Turkish flags at the entrance, the school had spacious classrooms with adequate supplies. In the joint first and second grade, which we visited, children learned to write in script in their first year; their notebooks displayed impressive penmanship. As one student read to me from her notebook, I happily noted that rote learning was a thing of the past. The curriculum was set by the Ministry of Education in Ankara.

The Eğridir market was enchanting with its orderly displays — large platters of olives, sorted by color and size, stuffed toys grouped and stacked by kind, and brooms arranged in eye-catching patterns lined the sidewalks. Ready-made wear on hangers filled makeshift racks under white canopies; even station wagons with open tailgates served as stalls for rugs or rose products. This region near Isparta, center of Turkey’s cultivated roses, produces a variety of creams and lotions derived from the flowers, in addition to rose water, used for flavoring.

Our driver recommended an alternate scenic route on our way southbound, which took us by a restaurant on Lake Eğridir. Following an enjoyable lunch of lake bass, we continued on our way, crossing the Toros Mountains, and arrived in Antalya, the center of the country’s citrus agriculture and a popular destination on the Mediterranean coast. Our bus left us outside the old quarter, where large vehicles cannot negotiate the narrow streets. We then walked to our hotel in Kaleiçi, the historical nucleus of Antalya.

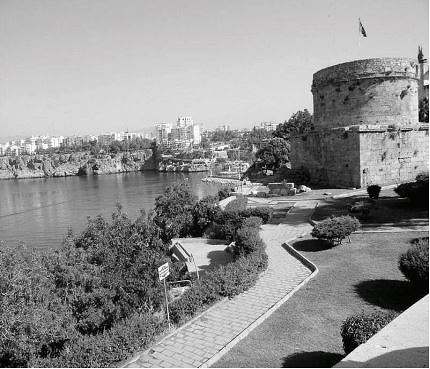

Antalya harbor

Antalya, the ancient Greek city of Attaleia, is set on a wide bay with mountain views all round. The old district within the fortress is now restored and has become an attractive tourist center with small hotels, restaurants, taverns, and shops. The streets lead down to the old harbor, which is now an international yachting marina. The coastline on either side of the marina is lined with resort hotels featuring modernized Turkish baths, boutiques, and apartment buildings.

Perge is an ancient city 18 kilometers northeast of Antalya. Dating back to 1000 BC, its surviving remains are Hellenic and Roman. Saint Paul is said to have preached his first sermon here in 46 AD. We entered Perge through its grand Byzantine tower-gate and walked around its theater, stadium, agora, baths, and aqueduct. A little further out is Aspendos, a major port and commercial center in antiquity, now inland 48 kilometers east of Antalya. It is known for its well preserved 15,000-seat amphitheater with superb acoustics, built in the 2nd century AD. During our visit preparations were underway for performances of Aida; concerts, which require sound systems, are no longer held.

Our final visit in Antalya was to the Archeological Museum, which houses regional artifacts dating from the Stone Age to the present. The museum’s impressive collection covers fourteen exhibition halls and an open air gallery. A unique display is a tribute to the archeologists, with their pictures and credits for the various digs.

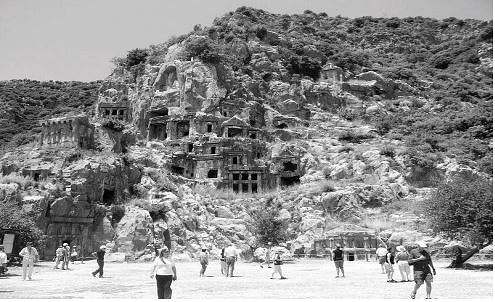

On the way to Fethiye, our next destination, we stopped in Myra to see the Roman ruins and the house tombs of ancient Lycia. The large Roman theater is still intact, with marble seats and mask friezes scattered around the elaborately decorated stage area. The Lycians, who practiced a type of ancestor worship, built the tombs in the 4th century BC. They are carved into the cliffs in ascending rows; the funerary bas-reliefs of the ornate facades fascinate viewers even from a distance.

The Lycians surrendered willingly to Alexander the Great’s army in 334 BC. Following a period of rule under Ptolemy, king of Egypt, and then Antioch, king of the Seleucids, Lycia fell to the Romans in 190 at the end of the Syrian War. While enjoying good relations with Rome, Lycia remained independent until annexed by Emperor Claudius in 42 AD.

The enduring legacy of the civic-minded Lycians is the model of government they provided. Their federation, established in 168 and known as the Lycian League, included 23 cities, each of which elected one, two, or three representatives according to the size of its population, with the six largest cities casting three votes each at the federal Assembly. Unique in its own time, the Lycian League has been a source of inspiration to the founders of democracy in countries throughout the world.

The most famous Lycian benefactor was Saint Nicholas of Myra, who inspired the legend of Santa Claus. Saint Nicholas was bishop of the region in the 4th century AD. Born of wealthy parents, he used his inheritance to make anonymous donations. He is best remembered for having spared poor girls from prostitution by secretly dropping money for dowries down their chimneys and thus making them marriageable. We visited the Church of Saint Nicholas in the town of Demre. Restoration work is underway on the church, which has fading frescoes and floor mosaics. A modern statue of Saint Nicholas adorns the entrance of the church as well as the town center.

House tombs of ancient Lycia

Driving across the Kekova Peninsula, we arrived in Kaş, a small town known for its cold underwater springs and crystal-clear waters. Its fame for underwater visibility attracts many divers, whose boats filled the picturesque marina. After a brief walk about town, and a spell watching fishermen mend nets and feed pelicans, we were on our way to Fethiye to begin a four-day cruise on the Turkish Riviera. The city of Fethiye, called Telmessos (Lycian for “land of lights”) in ancient times, sits at the border of Lycia and its neighboring civilization, Caria. Once a center of prophecy dedicated to the god Apollo, with a history dating back to the 5th century BC, Fethiye is set against cliffs adorned by Lycian rock tombs; a sarcophagus lies in the town center.

At the harbor, we boarded a Turkish yacht, known as a gulet. The first gulet yachts (from the French goelette, meaning “schooner”) evolved from seafaring vessels used by the ancient Carians, inhabitants of the southwest coast of Turkey. The yachts were fast and easy to maneuver — ideal for eluding pirates. Today gulet yachts are outfitted with powerful engines; they can rely on motor power or sails. Our gulet was a teak and oak beauty with an outdoor eating area and two observation decks with cushions, fore and aft. Its eight cabins, with showers, determined the size of our group — fourteen plus guide. To keep the boat clean we changed into flip-flops or slippers on board.

Our captain, a jolly Kurdish man from Malatya, and his crew of three young men from nomadic families took care of every detail on the boat. Our cook provided us with three delicious meals a day, including bountiful fresh vegetables, and never repeated the menu. As one of two native speakers of Turkish in the group, I was able to chat with the crew during off times. The captain had come to Antalya from eastern Turkey as a young boy to find a job. He had worked his way up as cook and then as captain, passing the required tests. He liked the seasonal nature of his job, as it allowed him to be with his family the rest of the year. The captain told me that he had no intention of leaving this “paradise” and living in another land, like some Kurds who “want their own country.”

Out of Turkey’s population of 72 million, some 15 million are Kurds. 50% of them live in the southeast; the rest have settled throughout the country, and many have intermarried. To accommodate the modified Latin alphabet used to write Kurdish (an Indo-European language, unlike Turkish), legislators are at work on a bill that would lift the present ban on use of letters not in the Turkish alphabet — such as q, w, and x — and the government is considering changing the names of some towns in the southeast back to their original Kurdish names. With Turkey’s increasing prosperity, including in the southeast, it is hoped that those fighting in the mountains for secession will soon have reason to settle down as content citizens.

During the cruise our first landing was in Gemiler Bay, from where we hiked to Kayaköy (Karmylassos), a ghost town once occupied by about 600 households of Anatolian Greeks. During the population exchange in the aftermath of the Turkish War of Independence, Turks relocated here from Salonika could not adjust to the rocky terrain and vacated the houses for farmlands below. The town is on an eerie hillside, with empty building shells amidst spreading bay, thyme, and fig and walnut trees, doomed to succumb to merciless vegetation.

Our daily schedule consisted of morning and afternoon hikes to see ancient sites, interspersed with swimming, reading, and resting. Our excursions took us to old churches and monasteries, as well as to Greco-Roman sites, such as Lydea, to which we hiked from the port of Ağa Limanı. Down a pine-shaded trail, we visited a shepherd’s family to break up our three-hour hike to Cleopatra’s Cove, which shelters the sunken baths of the Egyptian queen, built for her by Marc Antony. Legend has it that he gave the entire Turquoise Coast to his Egyptian bride as a wedding present. Our gulet sailed around to meet us. The highlight of this walk was a visit to the house of a shepherd called Mutlu. He, his wife, and his five-year-old daughter treated us to sage tea, homemade honey, and bread. As soon as I dunked my bread in the honey and tasted it, I knew I had to buy a jar — which I did.

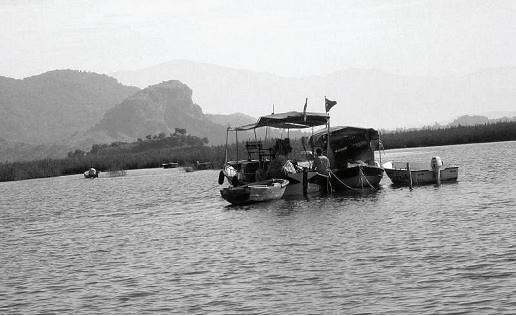

On the final day of our cruise, a small boat met us at Ekincik Cove and took us on a side trip up the Dalyan River, which snakes inland from the Mediterranean amid reeds and cattails. The river, whose name means a type of large fish trap in Turkish, provides striking views of Lycian temple tombs on steep cliffs high above the banks.

The Lycians were highly skilled stonemasons and used soft limestone found along the Turquoise Coast. They believed that the dead would be transported to the afterworld by bird-like creatures. Walking around the remains of ancient Caunus provided insight into Lycian life; our visit included the Terrace Temple, the Roman bath, the theater, the agora, the fountain, and the sacred precinct of Apollo. The inhabitants of this city certainly had spectacular sights to see.

The highlight of the Dalyan River boat trip was a sighting of rare caretta caretta, or loggerhead sea turtles, which have existed for some 95 million years. Each year the females return to the place of their birth near the Lycian ruins of Caunus to lay their eggs. The reddish-brown turtles grow up to 300 pounds and can live for 200 years. International conservationists have been helping to preserve their Turkish nesting grounds. The village of Dalyan, named after the river, is proud to be Turkey’s “Turtle Paradise” and is well stocked with turtle T-shirts and souvenirs.

Fishing boats on Dalyan River

Bidding a fond farewell to our captain and crew, we ended our Blue Voyage in Marmaris, where we met our minibus for the last leg of our trip, northward to the Aegean Coast.