May 2009

In May I accompanied a group of American friends on a three-week tour of Turkey. Although our itinerary — Turkey’s Magical Hideaways, arranged through Overseas Adventure Travel — included regions I had visited before, I knew there would still be discoveries for me, as Turkey is an evolving open air museum. Currently there are 33,000 archeological sites in the country. Most of these are in the Asian part of Turkey, Anatolia, whose name means “land of the East” in Greek. The Anatolian peninsula has served as a land bridge between Asia and Europe, home to 27 civilizations throughout history.

Upon arrival in Istanbul, our group flew to Gaziantep, the starting point of a pre-trip to southeastern Turkey. Our hotel, called Anadolu Evleri (Anatolian Houses), consisted of several historical buildings surrounding an inner courtyard. Restored and furnished in keeping with their history, they featured the owner’s collection of country antiques, which enhanced the buildings’ charm. My roommate Gayle and I occupied the bridal suite, with its wrought iron balcony overlooking a courtyard, where we had our meals.

The breakfast buffet introduced us to regional specialties, in addition to the regular fare of cheese, olives, tomatoes, cucumbers, and fresh-baked bread. Two items that stood out were zahter — cumin ground with sesame seeds, enjoyed with chunks of bread dipped in olive oil — and hazelnut spread with molasses, made by boiling grape juice and thickening it with yeast. Following a bountiful breakfast, we set out for our day journey to Antakya (ancient Antioch), located in the Orontes valley at the foot of Mount Silpius, 25 kilometers from the Mediterranean and 50 kilometers from the Syrian border.

Heading west and then south on a three-hour scenic ride, we passed by farmlands of wheat, barley, chickpeas, and lentils. Tents of seasonal workers dotted the countryside of olive and pistachio groves alternating with vineyards. Red poppies intermittently blanketed the landscape. Near snow-capped Mount Nur, we turned south. From a distance a minaret signaled Islahiye, a town of charming fruit gardens surrounding brick houses, where carpets hung from balconies for daily freshening. As we traveled south, solar panels appeared on rooftops and olive groves gave way to cotton fields, with textile factories joining in the scenery. On a hillside a slogan — “Önce Vatan,” meaning “Country First” — appealed to local patriotic sentiment.

Our first stop in Antakya was at the Hatay Museum, named after the province of Hatay, where some of the largest sets of 2nd, 3rd, and 4th-century Roman mosaics have been discovered. In addition to this mosaic collection, the museum houses artifacts dating back to Assyrian, Hittite, Hellenic, Roman, and Byzantine times. The mosaics depict mythological scenes of battles between gods and giants, as well as figures such as Daphne, Dionysus, Oceanus, and Orpheus, underlying Antioch’s fame as the “Queen of the Orient” because of its wealth of splendid artworks. The third biggest city in the Roman Empire after Rome and Alexandria, Antioch was also an important center of international trade.

Lunch was at the Anadolu Restaurant in the old town center, where we enjoyed Antakya’s famed grilled chicken and other local specialties, such as fresh thyme salad, humus thickened with lots of sesame tahini, and künefe, a dough-based dessert filled with melted cheese and soaked in syrup. The city center, lined with cafes, featured signs for künefe to entice passers-by. There is not much evidence of the old metropolis in the modern city due to terrible earthquakes and floods, and excavations are hindered by the fact that the city is built over the foundations of the ancient settlement.

A cosmopolitan city of half a million people, Antioch was fertile ground for the spread of Christianity due to its open cultural climate, which led the way to initial contact between Jews and “pagan” Christians. It was in this multifaceted city that the disciples of Jesus were first called “Christians” — a term designating a well defined group distinct from the Jews, who did not believe in Jesus, the Christ. Tradition has it that the first Christian community met in a cave church known as “Saint Peter’s Grotto.”

Saint Peter’s Grotto

Our visit to this church was my fourth, my first having been with my history teacher in my second year of high school. I have a class photo taken in front of the church’s oriental facade, made of local stone during restoration in 1863. It is believed that the grotto was given to the early church by Luke the Evangelist, a native of Antioch. Traces of the original floor mosaics remain; an earlier wooden altar has been replaced by a stone one, above which a white marble statue of Saint Peter sits in a niche. In 1990 a seat was installed behind the altar to recall the “Chair of Saint Peter in Antioch.” The Capuchin fathers, representatives of the Catholic Church in Antioch since 1846, celebrate mass here on the main festivals of the liturgical calendar, including midnight mass on Christmas Eve. Proclaimed by the Vatican as a holy place in 1983, the grotto is nestled in a hillside with sweeping views of the modern city below.

Heading back to Gaziantep, we were led by our tour guide, Nedime, on a wonderful discovery of the eastern slopes of Yeşemek, a village 27 kilometers southeast of the town of Islahiye. In the Yeşemek Open Air Museum, we wandered amidst stone lions, sphinxes, and mountain gods dating back to 2000 BC, the Hittite period. This site, discovered in 1890 near a quarry, was the largest sculpture workshop in the Middle East; here basalt blocks were roughed out and shipped unfinished to other destinations. A visually exciting tour shows these blocks of stone in different stages of processing.

Upon returning to the hotel, we were met by a delightful surprise. Attracted by loud music nearby, we walked over to find that this was a send-off party for a young man reporting to military service. Relatives, friends, and neighbors filled an off-the-street courtyard; women sat along the perimeter, while men and children, including the recruit in a white shirt, danced in the center. Sending a son off to the army is considered an honor for most traditional families; in case of loss they are comforted by the fact that their son died for his country. The city is renowned for the bravery of its inhabitants in 1920, when it was attacked and occupied by French forces. Since the enemy were forced to withdraw, the Grand National Assembly later recognized the city for its heroism by bestowing the title Gazi, or “veteran,” onto its original name Antep.

Later in the evening, we walked over to a nearby baklava shop to indulge in this pastry — made of phyllo dough soaked in honey and filled with pistachio nuts — which contributes to the fame of Gaziantep. We then stocked up on pistachio crackers as gifts, as Gaziantep is the only city where this gadget is found.

Due to its strategic location between northern Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean, Gaziantep was one of the earliest settlements in Anatolia and has been home to many civilizations throughout history. The attractive city museum houses a wide variety of artifacts, ranging from Neolithic skeletons to Hittite pottery to Roman mosaics and statues.

Excavations at the site of Zeugma, prompted by finds during construction of a nearby dam, have increased recognition of the city, which has now risen, in terms of world archeological activity, to second place after the large dig in Tunisia, surpassing Antioch and its extensive collection of Roman mosaics. Although much has been looted and taken out of Turkey, there is still plenty to see at the museum, making the visit a worthwhile experience.

Other highlights of our Gaziantep tour were lunch with a local family, a boat ride on the Euphrates, and a visit to the Atatürk Dam. Over lunch we visited members of a traditional family — mother, daughter, son, and his wife, who in-laws refer to as the “bride” or gelin. The bride always moves in with her husband’s family, and is called gelin no matter how long she has been married. She is basically the right hand for her mother-in-law in performing household chores.

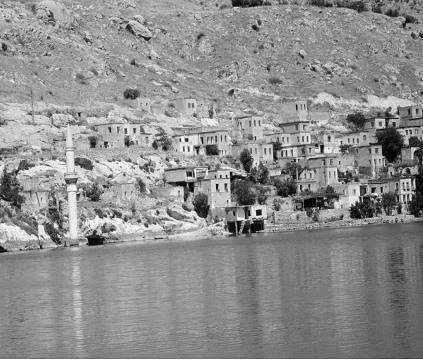

Sunken city of Savaş Han

Driving east, we stopped briefly in the town of Birecik to view a bird sanctuary known for its black ibis, and continued on to the town of Halfeti, where we boarded a boat. We cruised to the Roman fortress of Rumkale, built in 840 BC and dominated by many powers throughout history, and then to the sunken city of Savaş Han, a victim of rising waters due to the dam project. A single minaret rose from the water at the river’s edge, its mosque submerged.

The dam construction project involves a total of 22 dams, fourteen on the Euphrates and eight on the Tigris. Costing 32 billion dollars and projected to be finished in 2010, it is to irrigate 80% of the country’s farmland. The Atatürk Dam is the biggest in Turkey and the fourth largest in the world, with 26-kilometer-long irrigation tunnels connecting to other canals. A park at the dam entrance is open for recreation; people come here to cool off and to picnic. There is a memorial sculpture in the park to commemorate those who have lost their lives during construction.

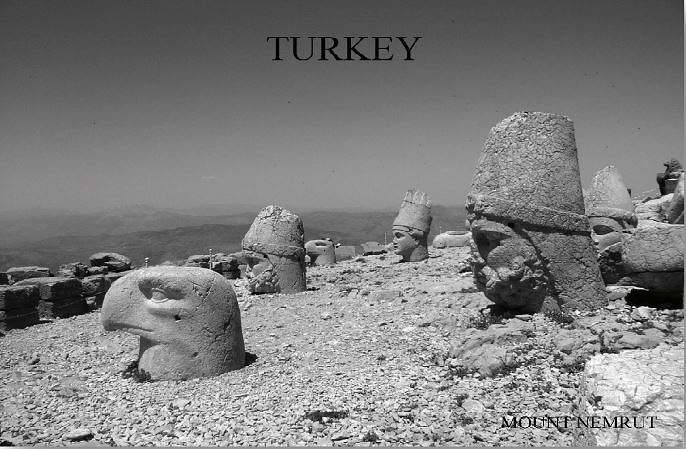

Our next destination was the city of Adıyaman, where we spent the night before embarking on a new adventure — ascending Mount Nemrut. One of Turkey’s most fascinating ancient sites is the 1st-century BC tomb and shrine of King Antiochus I of Commagene on top of Mount Nemrut in south-central Turkey. Antiochus I, who governed a small kingdom, believed that he was of divine descent, and ordered the construction of a great tumulus to immortalize him beside the gods. Colossal heads and crumbling statues of gods, animals, and King Antiochus himself surround three sides of a 50-meter bare tumulus above the original 2100-meter mountain, now a national park.

Mount Nemrut is northeast of Adıyaman, where we spent the night and stocked up on groceries for a picnic lunch to follow our ascent. Looking for bread in the morning, we stopped at a village to ask for directions to a nearby bakery. Instead we were offered several loaves of homemade bread by a family, who would not accept money in return. This was one of many instances of Turkish generosity and friendliness we encountered throughout our trip.

On our way to the mountain, we stopped at the Karakuş tumulus, the memorial grave of the Commagene royal family. Columns holding an eagle, a lion, and a bull guarded the base of the tumulus. A walk near the Cendere River, across a Roman bridge built in 200 AD, was yet another reminder of the ancient history of these legendary lands. Marked by two tall columns at either end, the bridge straddled the river, called Chabnes in Roman times. According to an inscription it was built by the 16th Roman legion.

Dropped off at the entrance to Nemrut National Park, we started a gradual climb on a rocky path, trailing other hikers and donkey taxis. This was my second ascent of Mount Nemrut, the first having been fifteen years earlier, when I had braved the chilly air on the mountaintop to watch the dawn light the faces of the statues. Equally popular is the spectacle at sunset. On the east terrace of the tumulus are 8-10-meter statues of gods, guarded by a lion and an eagle. The line-up includes Zeus; the sun gods, Apollo and Mithras; and the god of war, Heracles. On the west terrace is a relief of Antiochus shaking hands with the gods. A head of Fortuna, goddess of good fortune, her hair depicted as wheat stalks, shares the terrace with other gods. The stone gods are now chained off, due to an increased number of visitors. Nevertheless, we managed a group photo with the seated gods as a backdrop and their broken heads nearby.

Following a leisurely walk around both the east and west terraces with sweeping views of the hillside, we descended to the cafe at the entrance for a picnic lunch. Having worked up an appetite, we feasted on food purchased by our guide, Nedime, from our wish list, which included spicy Turkish sausages cooked for us at the cafe.

As we ate, my eyes wandered to the walls, which displayed the southeastern region’s unique sumak carpets, embroidered with silk motifs after they are woven. Deferring such a purchase, I settled for a hand-embroidered red hat to add to my collection of gifts for friends. After lunch we headed south to catch the car ferry across the Euphrates to the town of Siverek, where we connected to the highway to Urfa, our base for the next two nights.

Urfa — Edessa in Roman times — is one of the oldest cities in Anatolia, dating back to 11,000 BC, in the Neolithic period. It is in the central Euphrates region, near the Syrian border. Known as a “museum city” because of its rich architectural heritage and skyline of varied minarets, it is also called the “City of Prophets.” It is here that the prophets Jethro, Saint George, and Job are said to have lived, and the city claims the distinction of being the birthplace of Abraham. It is the fourth most sacred city in the world to Muslims after Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem.

Urfa derives its culture from its layered history — Greek, Persian, Arami-Suryani, and Ottoman. Due to its religious grounding and large ethnic populations of Arabs and Kurds, it is one of Turkey’s most colorful, yet traditional communities. Typically, men wear baggy pants and blue headscarves, while women don long coats and distinctive Urfa scarves of lightweight silk, often blue and embroidered. Men with blue scarves wrapped around sun-drenched faces, enjoying a dice game or rolling tobacco, and women, heads unified in blue and chatting while their children play, enrich the local color.

Our hotel — which bore the city’s Arabic name, El Ruha, meaning “with plentiful water” — was centrally located in the old part of town. Across the street, a new Roman excavation, not yet open to the public, was underway. A quick walk under an excavation canopy, providing shade from the 80º heat, allowed us a glimpse of the painstaking work such a dig requires. Mosaics dormant for millennia were being awakened by careful raising of the slabs, with pieces fitted together like those of a jigsaw puzzle. Their features, revealed under a fine haze of dirt, begged for deep cleansing.

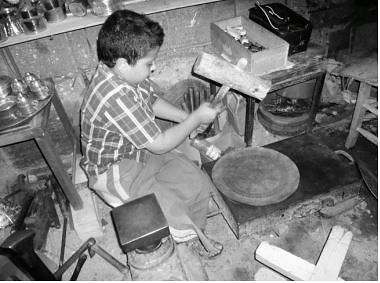

Child apprentice in copper shop

The historic landmarks of the old city include a citadel with two late-Roman columns, Abraham’s cave in the Mevlid-i Halil Mosque southeast of the pools, the 12th-century Ulu Cami (“Great Mosque”), and the 13th-century religious complex of the Halil ar-Rahman Mosque, which shimmers in one of the sacred pools associated with Abraham. Not far from the pools is the old bazaar, a place whose crowded streets, goods, methods of manufacture, and ways of bargaining have not changed since Ottoman times. Trades are passed on from fathers to sons, who become apprentices at a young age.

Our pre-trip group of eight split up to enjoy the different sections of the bazaar. Gayle and I walked down an alley of coppersmiths and watched them hammer thin sheets of copper into ewers, pitchers, mugs, and fanciful trays. Objects to be used with food are tin-plated afterwards. A textile section, with vibrant colors and swirls, many imported from Syria, was a feast for the eyes. An alley with small shops stacked to the ceiling with carpets was the most enticing. We enjoyed tea in clear thin-bellied glasses, while shopkeepers unrolled their inventory. After some bargaining, I settled on a sumak carpet for my Istanbul apartment. Its diamond patterns alternate with fields of colorful little birds embroidered in silk.

The local flair of Urfa extends to its food as well. The famed red peppers, isot, come in different strengths and are sold in specialty shops. Urfa kebab consists of skewered, isot-flavored meatballs with tomatoes, sliced onions, and hot peppers. Yogurt is a main staple of various dishes, and şıllık is a favored pastry made with walnuts.

Harran, a small town in the south, within Urfa province, was a highlight of our pre-trip. Our visit began with a tour of the 13th-century fortress, which is surrounded by walls with five gates. Other features of the old town include a group of beehive-shaped houses and the ruins of a temple-university complex. A prosperous Assyrian city on the crossroads of Mesopotamian commerce in ancient times, Harran was home to the world’s first university. It is considered an important site for Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, as Abraham is thought to have been living here when he heard God’s call.

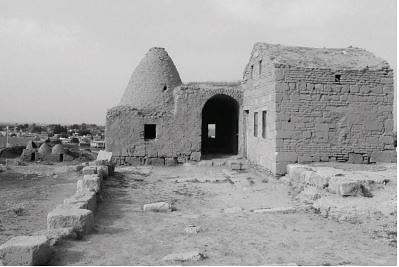

Harran house

The unique architectural style of Harran houses, with their red bricks and dome roofs, has been an answer to the steppe climate of the area since the time of the Hurians. Conical structures built in units of two, three, four, or six connect through interior arches. They remain cool in the summer and retain heat in the winter. Built by their owners on square lots, they were occupied until 1985, and are now used for storing food or hay. Residents have moved to contemporary housing near the dam in New Harran, within viewing distance of the old town.

The Harran Cultural Center, which occupies nineteen of the conical units, has restored and furnished them in keeping with tradition. The Center is owned and run by an Arab family, who hosted us for dinner. After a tour, we settled down on a canopied outdoor platform on stilts. Seated on floor cushions against a backdrop of ancient ruins, we enjoyed a delicious meal — stir-fried free-range chicken, vegetable stew, cracked wheat pilaf, salad with pomegranate vinegar, and homemade bread, accompanied by sour cherry juice. Our hostess, who we never met, had prepared the food in her kitchen in the new town and sent it over to feed our group of ten, including guide and driver.

Our host, who had fourteen children and sixteen grandchildren, was very proud of the size of his family. We met most of his children who were not away on military duty. Boys helped run the cultural compound, including guiding tours; girls helped their mother with household chores and took care of younger siblings. The family, who had migrated from Iraq several generations ago, spoke Arabic among themselves. The Cultural Center was founded on their inherited property.

My first visit to Harran had been about fifteen years earlier. The old town had not been deserted then. There had been much visible poverty, with barefoot children begging for pencils. So I was happy to see the progress made since my previous visit. All children, including girls, now attended school, compulsory for the first eight years; and most went on to high school in New Harran. Instead of begging, children sold crafts they had made themselves to earn pocket money. I bought several hanging good luck objects for the home, known as üzerlik, from two girls. These are made of seeds which look like small chickpeas. Girls string the seeds, alternating them with ribbons or colorful cloth.

When we approached Urfa Airport the next morning, our plane could not land due to sandstorms from Syria. Turkish Airlines took us to Gaziantep, where we caught our Istanbul flight. We boarded the plane, looking forward to further glorious adventures.