SOUTHEASTERN TURKEY

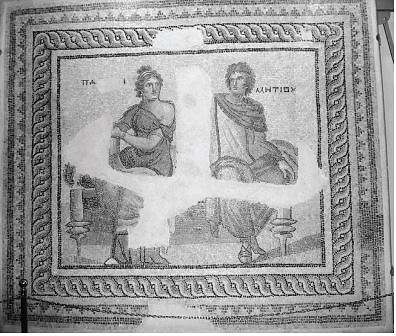

Roman mosaic in Gaziantep Museum

May 2008

Southeastern Anatolia is a distinct part of Turkey culturally and geographically. This is Mesopotamia, the Land between the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers. With the demise of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War, Mesopotamia was divided by the Allies to create national boundary lines for Iraq and Syria; Turks fought successfully to retain parts of the land. Inhabited by Arabs, Armenians, Jews, Kurds, Suryanis, and Turks, the ancient cities in this area retain a cultural richness like no other.

During my semiannual visit to Istanbul, I looked online and found a three-day domestic tour of Southeastern Turkey on the occasion of the national holiday on May 19, which commemorates the beginning of the War of Independence. Delighted with the opportunity to go to a part of the country mostly new to me, I quickly signed up. My sister joined me on the tour.

Our flight from Istanbul to Adana took an hour and fifteen minutes. Adana is Turkey’s fourth largest city and serves as a gateway to the southeastern part of the country. It sits between the Taurus Mountains and the Mediterranean Sea, and is known for its fertile meadows and citrus groves, as well as the İncirlik Air Base. From Adana we traveled by minibus to Gaziantep, formerly Aintab, near the Euphrates. In recognition of the city’s year‑long heroic defense against French forces in 1920, the Turkish Grand National Assembly bestowed it with the title gazi, meaning “veteran,” in 1921. Thus the name Gaziantep was born.

The highway between Adana and Gaziantep is a 90-minute ride, with an occasional glimpse of oleander fields, passages through numerous mountain tunnels, and a sighting of a 13th‑century bridge comprising fourteen arches over the River Seyhan. As we approached Gaziantep, we passed by a village full of cherry orchards and entered the city through its two-arched portal. In hindsight we realized that flying directly to Gaziantep would have saved us time for sightseeing in this fascinating city.

On the ancient Silk Road between China and Antioch, Gaziantep is Turkey’s sixth largest city, with a population of 1.2 million. One of Anatolia’s earliest cities, it is now a major center for industry and medicine. It exports metal, chemicals, and food products, as well as textiles. Its hospitals serve patients from Iran and Syria. Gaziantep is also a city of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine antiquities; Seljuk and Ottoman architecture; unique handicrafts; and local cuisine. Its famed pistachio nuts and baklava travel the world.

Our first stop was for lunch at a restaurant called Çağdaş. Catering to both locals and tourists, the establishment is famous for its lahmacun (thin pizza) and for its kebabs and sweets. New to me was “carrot baklava,” so named because of its shape. This delicious dessert was a reminder that traveling in Turkey means leaving one’s diet at home. Then we strolled through the Long Market, which was packed with big sacks of herbs and spices, dried fruits, and nuts. The market has a maze of alleys designated for copperware, woodcraft, slippers, textiles, and so on.

The Gaziantep Museum is a treasure trove of artifacts excavated from the region. Recent excavations at the site of Zeugma have made the collection of Roman mosaics in this museum the second largest in the world after the one in Tunisia. The size of the collection is due to discoveries made during the Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP), a system of 13 construction plans irrigating and providing hydroelectric power to over 4 million acres of land in the Euphrates and Tigris valleys. Before rising waters claimed them, the frescoes and mosaics of two Roman villas dating back to the 1st century AD were relocated to the Gaziantep Museum. Also discovered in a clay quarry during dam construction was a large Bronze Age cemetery, where 8000 ceramic vessels were found in 320 graves. The world’s largest collection of bullae (clay and metal imprinted seals), with 65,000 pieces, is in this museum.

On the way to Urfa we stopped at the town of Birecik, the site of one of the dams, but also a bird sanctuary on the migration route of the black ibis. Birdhouses dotted the side of a cliff to attract the birds. The glossy black ibises with long curved bills were a delightful sight. We continued on the highway to Urfa.

Urfa’s settlement history goes back to the Neolithic Age. However, it is in the 2nd millennium BC that it flourished as the Sumerian city of Ur. This is the biblical birthplace of Abraham and is also known as the City of Prophets. It is here that the prophets Jethro, Saint George, and Hiob are said to have lived. In the 12th century the Crusaders held the area for 50 years and built a citadel. Many of the current population of 480,000 people are Arabs or Kurds. In recognition of the valor of local resistance forces against the British and French in 1920, the city was renamed Şanlıurfa by adding the title şanlı, meaning “glorious.” It is simply known as Urfa in daily language.

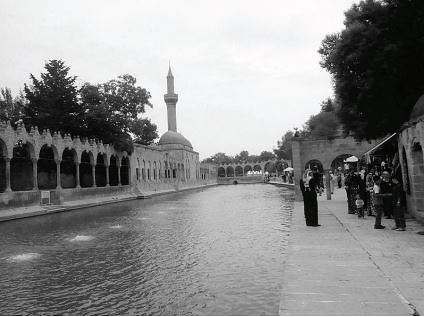

Pool by Abraham’s cave in Urfa

Abraham is said to have been born in a cave. People travel long distances to visit Abraham’s birthplace. Men and women go through separate doors to enter the respective prayer chambers. Women must have a head cover and clothing with sleeves. The cave is by a pool surrounded by a religious complex and attractive gardens. Hundreds of plump carp frantically devour bread thrown by visitors into the pool, which is fed by a spring at the foot of the citadel. According to legend, King Nimrod, who ruled over Urfa, had Abraham immolated on a pyre for destroying idols, but God turned the fire into water and the burning logs into carp. So carp are considered sacred, and feeding them a holy act.

A legendary local pepper, known as isot, is unique to Urfa cuisine. Ground hot peppers in different shades of color and intensity are used in different recipes and sold in specialty shops. We visited a shop called İsot Evi (House of Isot), with chains of dried red peppers looped around the interior, giving it a festive look. Big bags of ground peppers, ranging from almost black to light red, sat on the floor. Each bag was labeled differently — for example, for “meat balls” or “dishes with sauce.” The group stocked up on a variety of peppers, sold by the kilo or gram, to take back to Istanbul.

Urfa’s bustling ancient bazaar is a cross section of life in the city. An overwhelming feast for the eye, the typically Eastern bazaar is crammed with small shops of copper workers, tobacco vendors, and fabric stalls. Heaps of silk or polyester, mostly imported from across the border from Syria and therefore cheaper, beckon women, who buy the fabrics as head covers. I bought a square piece of local black silk with a colorful swirling pattern from a vendor who spoke Turkish to me and Arabic to his assistants.

We stayed at the centrally located Arte Hotel. Dinner was at the Beyzade Konak Hotel, a former Ottoman home, where we attended a sıra gecesi. This is a local custom where men take turns entertaining each other over food and music in their homes. Our dinner featured patlıcan kebap — lamb with eggplant — and çiğ köfte — meatballs made by kneading ground lamb seasoned with isot for a very long time. The latter are eaten uncooked and are usually served as an appetizer. Since this was an evening for tourists and preparation of the appetizer was part of the program, we sampled it as a second course. Şıllık — walnut pastry — preceded the final course of crepes with pistachios. The entertainment included songs by a young male folksinger accompanied by local musicians, dancing, and a henna ceremony.

On our way out of town the next morning we stopped at the holy fountain of Prophet Eyüp, erected near a well where the prophet is said to have miraculously recovered from leprosy by drinking the water. Believers lined up to peer at the well and touch their foreheads to it, as well as to drink from the fountain. On the road to Mardin we drove through areas around Urfa affected by the new dam. The dry valleys of Upper Mesopotamia are turning green.

The city of Mardin is built on top of a 1083-meter-high mountain overlooking the Northern Mesopotamian Plain and bordering the Tigris. This region was first settled by nomadic hunter-gatherers in 5000 BC. Since then it has been ruled by Hurians, Hittites, Assyrians, Persians, Armenians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, and Seljuks, finally coming under Ottoman reign in 1517. In 1919 the French attempted to subdue the area, but withdrew, faced by the resistance of Mardin’s citizens. On November 21, 1921, the borders of modern Turkey were established with the signing of the Lausanne Treaty, and Mardin became a center of regional government.

As a result of its rich heritage, Mardin is home to different ethnic groups. Many of the Muslim and Christian populations speak their mother tongue — Arabic, Syriac, or Kurdish — as well as Turkish. Church bell towers and minarets share the skyline, adorning the city with great architectural wealth.

The first example of great architecture that we visited was the medrese (religious school) of Kasımiye. An impressive portal greeted us at the end of the steps leading to the entry. Built in the 15th century, the two-story theological school has a mosque to the left and a reflecting pool in the courtyard. Its simple glamour lies in arches, double domes, and inscribed stone signs indicating the subject taught in each classroom.

Children selling beadwork

The caretaker of the medrese, a Kurdish man with seven children, introduced us to one of them. A beautiful young girl, she was selling her own beadwork along with other children. They had set up tables facing the school, with the Mesopotamian Plain as a backdrop. To support their craftwork, we all bought beaded necklaces or bracelets.

At an elegant restaurant, a former Mardin home, we sampled local delicacies. The first course was mint-flavored cold yogurt soup made with chickpeas and wheat kernels, followed by two types of içli köfte — meatballs coated with cracked wheat — boiled and fried. The main course was kazan kebap — lamb with eggplant, onions, peppers, and tomatoes — accompanied by rice pilaf and caper salad seasoned with pomegranate vinegar. Semolina halvah and Turkish coffee topped off the meal. Capers are plentiful in this region; pomegranate vinegar and sumac, in addition to hot peppers, are favorite flavors.

The city of Mardin was festooned with flags, along with Atatürk’s proverbs, stretched across streets in Republic Square because of the national holiday. Walking around, we dropped into a shop selling almond sweets, a specialty of the region, where almonds are plentiful. The shop featured raw and roasted almonds, as well as almonds coated in different flavors as sweets. The nuts were displayed in big sacks in the open, tempting visitors to sample and purchase them. We indulged.

Four kilometers outside of town we visited the Deyr-ül-Zaferan Monastery, which took its Arabic name from the yellowish-saffron color of its walls. Former home of the Syrian Orthodox Patriarch (1166-1932), the monastery is still an important center for the church, although the Patriarchate is now in Damascus. The structure was built in the 5th century AD, on the original site of a Roman fortress dating back to the 3rd century. The three-story monastery sits on top of an ancient sun temple on a mountain slope. A priest with long beard and flowing black robe gave us a tour of the complex, which reached its present size in the 18th century and includes three Byzantine churches, dormitories, a school, a cemetery, and cells for seclusion. In Syriac this place is called Fadayso, meaning “paradise.”

Kırklar (“The Forty”) is the most active church in Mardin. It is entered through an old, heavy iron gate. The building stands on the east end of a long courtyard, and is supported by arches upon 12 thick columns. The 6th-century church has a rectangular plan, with icons of saints, various handmade curtains, and clothes for the altar. The church takes its name from 40 Christians who are said to have lived around Cappadocia and to have been executed by the Romans in 240 AD.

In the mid-1800s, when Protestantism found sympathy among the Syrian Orthodox Community, American missionaries opened a college and hospital in the region. They educated local Christians, mostly Armenians, until the Lausanne Treaty, and Turkish children afterwards. Missionary activities came to an end in the 1960s, and the buildings were transferred to the state.

Mardin is home to 800,000 people, who have accumulated a rich mythology. A myth or folktale pops out from every corner. A favorite one is “Shahmeran,” or “Snake Woman,” about a creature with the body of a woman above the waist and of a snake below. She has horns, a snake’s tail, and feet made of snake heads. Snake Woman is considered a symbol of good luck and fertility, and almost every home in the area has a picture of her. In Mardin, where snakes are plentiful, this legendary creature has been immortalized in the work of coppersmiths and stonemasons, as well as painters and authors.

Stonemasonry is a revered profession in Mardin. Because of its durable nature, stone is the preferred material for construction. Most old houses within the city are made of limestone or basalt, cut by hand at nearby quarries. Various specialists reputed within the trade cut, grind, shape, and draw patterns on the stones. Placing the stone in keeping with architectural design is yet another specialty.

Visiting a Kurdish family in one of the stone houses in the countryside gave us a glimpse of daily life. People living here, where women dress in colorful patterned fabrics, depend on spring water for their needs. Pure water descending from the mountain is fed into channels, which run the length of the living room under the dining table in each house. From here the water is directed under the stone patio out to a small pond and eventually to the garden, giving life to the plants. The channels of water serve as refrigerators as well, keeping fruit fresh and drinks cold.

Mardin has eleven districts within the ruins of the city wall. The quarter of Ulu Cami (the Mighty Mosque) takes its name from the city’s most architecturally recognizable symbol, with its segmented dome and bulbous 61-meter-tall minaret. The mosque overlooks the Mesopotamian Plain — the “ocean,” as locals call it — and is the single image that consistently appears on postcards, posters, and book covers. The mosque sits on a raised foundation of carved stones on a rectangular piece of land. A flower-figured Kufi inscription on its base states that it was built by the Seljuks in the 11th century. By the mosque is a tea garden, where we enjoyed the expansive view below over Turkish tea in thin-bellied glasses.

Nearby are many more historic treasures — the post office, the High School of Commerce (a vocational school for girls), the Şehidiye and Melik Mahmut Mosques, and the medrese of Zinciriye, to name a few. According to legend, the latter site once had attached to its twin domes a great chain that bore a blue and white bead protecting people from the evil eye of envy — hence the name Zinciriye, which means “chained.”

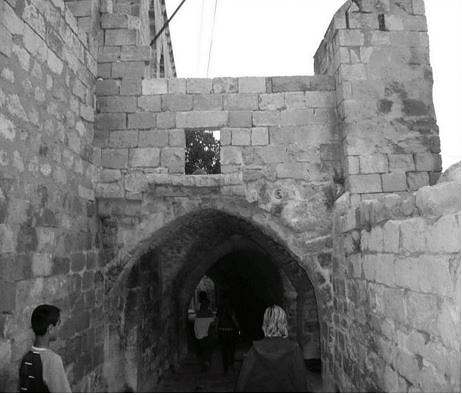

Typical “abbara” passageway

Besides such landmark buildings, the districts of Mardin are a maze of narrow medieval streets and alleys, some with steep stairs. The streets are lined with stone houses with flat terrace roofs, many with potted plants. The way the houses are stacked up on the hillside, the roof of one becomes the terrace of another. A walk through the streets reveals interesting metal doors embellished with decorative elements and plaques. The abbara (path running under a house) is a characteristic feature of Mardin homes. These passageways connecting alleys belong to the municipality, while the house above is privately owned. Rubbish is collected by city donkey service.

Our hotel, the Artuklu, a restored caravanserai built in 1275, was within the city walls in the old town, which has been declared a heritage site by the Turkish Ministry of Culture. We enjoyed a buffet dinner at the hotel, which has an old charm, including its small sleeping rooms. Dinner featured dishes made with the region’s own plentiful crops — spring soup with beets and carrots; a variety of salads with chickpeas, lentils, almonds, and walnuts; and lamb kebab with eggplant. A sweet pastry called tulumba (fluted cylinders of fried dough dipped in syrup), along with fresh apricots and strawberries, were the choices for dessert. After dinner we drove to a promontory to view Mardin’s nightscape; the hillside shimmered in lights. Having had a long day, we returned to our caravanserai in anticipation of the next day’s journey.

Traveling 24 kilometers east of Mardin through a terraced green landscape with grazing sheep and mud brick houses, we reached Midyat, 1000 meters above sea level. In the same province as Mardin, Midyat is the holy center of the region’s large Syrian population, who fast 79 days of the year. From 9th-century BC Assyrian tablets, Midyat’s original name is understood to have been Matiate, meaning “Cave City.” Early inhabitants lived here with their animals in caves.

There are two parts to the city, the old and the new. The old districts have retained their historic character, with houses resembling the stone houses of Mardin. Columns, arches, and the frames of gates and windows are all adorned with different motifs. In 2001 the town was officially declared a historical site, with 199 registered structures of historical value, including churches and mosques. Stonework continues in new constructions, with thick walls and windows which avoid facing those of other houses.

Midyat is famous for its telkari (filigree) and silver crafts; it is known as the birthplace of filigree work. This unique craft is produced by embossing carved wood with designs in silver or gold wire. Telkari masters produce jewelry and boxes, as well as delicate bags and belts with a variety of motifs. The main street is lined with small silver shops, where we spent an hour going from one to the next. I bought a silver filigree bracelet with a flower motif and a leaf-shaped ring at modest prices, as each was sold by weight.

Descending from the clay soil of Midyat, we reached a valley with almond and walnut trees and vineyards. The Tigris runs past the town of Hasankeyf and flows southwards in serpentine curves, on lands which have hosted many civilizations and have been a battleground between East and West. Barges for trade and transportation once plied the waters of the Tigris, and royals set up thrones in the cool breeze of the riverside. The golden years of Hasankeyf were under the reign of the Artukids between 1100 and 1234. The town remained under Ayyubis sovereignty from 1234 until 15th-century Ottoman rule.

An engineering feat of its time, a monumental stone bridge with ten arches was built by the Artukids over the Tigris. The legs of the old bridge stand in the water, parallel to the modern bridge, as a reminder of the town’s glorious past. Ruins of the ancient city are on hills overlooking the river. Tombs, mosques, medreses, and palaces dominate the river view. 6000 caves lurk in the high hills, which are believed to have been a center for ancient cave-dwellers. The rocks on the skirts of the hills are soft and easy to tunnel into. It is believed that the caves here may have been made by people seeking security or religious retreat. Residents of Hasankeyf lived in these cave homes until the 1970s. Today they live in a village on the bank of the Tigris. They use the caves as barns or stables, and even as souvenir shops and cafes.

Hasankeyf bridge ruins

In the late 20th century, Hasankeyf came close to being flooded by the waters of the Tigris because of the Ilısu Dam. The dark days of flood watches drew journalists and cameramen from far and wide. Under the media spotlight, the town became a focus of interest for both local and foreign tourists. Until 2000, Hasankeyf was a town where civil servants such as teachers, military officers, and police often went for duty.

Tourism seems to have benefited local children, who give tourists information on historical sites in English or Turkish. They recite everything by heart. Boys also sell postcards and books, while girls sell the local craft, üzerlik, made by stringing dried seeds like small chickpeas interspersed with colorful ribbons. Üzerlik pieces are decorative folk items thought to bring good luck to the home. After a little girl assured me that she herself had crafted the pieces she was selling, I bought one with pink and blue ribbons.

The flow and smell of the river; fishermen throwing nets in to catch shebot, the local fish; and tranquil tea gardens with hammocks are part of daily life. People walk down to the riverbanks in summer, when there is less water, and set up throne-like seats for rest and relaxation. These high seats also provide protection from scorpion bites. The river, set amidst impressive history, also draws tourists. Since our tour was over a holiday weekend, there were many school groups around. I pledged to return to this town on a weekday, when not as many tourists would be there, but soon, before rising waters sealed its fate.

Diyarbakır, northwest of Hasankeyf, was our point of departure for Istanbul. A major walled city with 82 towers and seven gates, built by the Roman Empire in 369 AD, Diyarbakır has a largely Kurdish population. We entered the city just as the noon prayers ended. Men in skullcaps poured out of Ulu Cami (the Great Mosque) into its large courtyard, surrounded by arches. As they walked toward the street, with prayer beads in hand and some holding canes, we could tell that we were in a very traditional city. The few women around were mostly wearing long coats and headscarves.

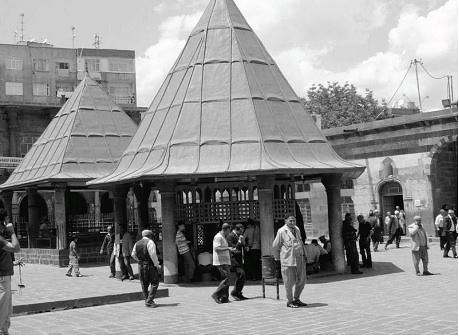

Ulu Cami is the centerpiece of an architecturally rich religious complex. The courtyard is surrounded by buildings constructed from black stone and basalt and ornamented in carved stone relief. At ground level the buildings have niches for sitting, and their windows are covered with latticework. Central to the courtyard are two impressive ablution fountains with conical, segmented copper roofs supported by stone columns.

A brief walk outside of the mosque complex was enough to convince me that this was a city I wanted to explore at leisure, and not on the way to the airport. Diyarbakır’s famed copper and kilims, as well as its kadayıf shops beckoned. Kadayıf is a sweet made of shredded wheat which has been roasted, soaked in syrup, and topped with ground pistachio nuts.

Those tempted to travel on a similar itinerary need a minimum of five days. The three days we had did not do justice to the cultural richness of southeastern Turkey.

Ulu Cami ablution fountains