ON THE SILK ROAD

October 2007

Traveling to Turkey twice a year gives me an opportunity to explore areas of the country unknown to me. While I was in Istanbul in late October, my sister and I enjoyed a two-day tour to Beypazarı, a historic town 100 kilometers west of Ankara. The tour, booked online, cost around $150 per person including bus fare, hotel, and most meals.

It took us a full day to reach our destination on the historic Silk Road from Istanbul to Baghdad, because of multiple stops for sightseeing and tea breaks. Turks are heavy tea-drinkers. Our first stop was in the town of Sapanca, which sits astride a lake of the same name. Trout fishing is the major industry in the area, which was known as Bithynia in around 1200 BC. We drove by white cherry and quince orchards and many vineyards. The landscape grew greener as we crossed the Black Sea region. We then began climbing winding mountain roads, ears popping as we gained height, and arrived in the town of Taraklı amidst poplar trees in their golden-yellow autumn glory.

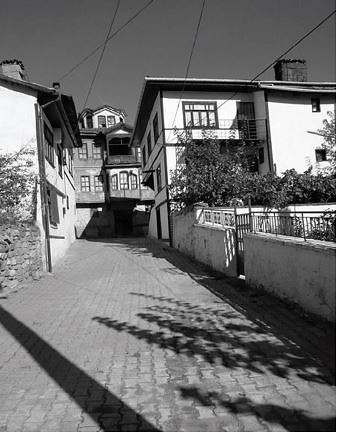

Street in Taraklı

Taraklı is an old Ottoman town which takes its name from its comb industry, the Turkish word for “comb” being tarak. The houses, most of which are over 150 years old, are under renovation by the government. One of these buildings serves as the Museum of Ethnology, with kilims on the floors and low divan seating along the perimeter of its small rooms. A short distance away is Göynük, a picturesque town situated on hills and valleys and surrounded by lush mountains and lakes, which are popular resorts. We stopped at Lake Sünnet for tea; one hotel advertised itself in English as a place for a “natural bypass.”

According to archeological finds, the first inhabitants of Göynük were Phrygians. After changing many hands, it became Ottoman territory in 1323. Following lunch, we walked around the town’s architectural treasures — a 14th-century mosque; a public bath, still in use; and the Akşemseddin Mausoleum, built in 1464 by the conqueror of Istanbul, Sultan Mehmet, in honor of his teacher, who was from Göynük. Of more recent vintage were 19th-century Ottoman homes and the Victory Tower, built in 1922 to honor those who had fought for Turkey’s independence. The three-story tower stands on an octagonal stone foundation. Despite a major earthquake in 1967, these structures, all on narrow cobblestone streets, are still standing and have been restored.

Göynük is rich in underground lignite, and its economy is driven by its poultry industry and agriculture. Its major crafts are copperware, woodwork (especially spoons), embroidery, and textiles. Large white head covers, worn by local women, have colorful stylized flowers along the borders with small black motifs in the center. I had to have one of these printed fabrics, sold for around $5, to use as a tablecloth.

Continuing on the Silk Road, we descended from the mountains to a plateau of arid beauty with varying earth tones. Sculpted hills with flat tops surrounded brown, beige, and ochre fields. Around us Nallıhan goats, typical of the region, grazed on stubby green plants which pushed through red and gray clay soil. In this Anatolian heartland, surrounded by steep and barren yet picturesque hills, sits Beypazarı. A well protected town, Beypazarı has been inhabited by Hittites, Phrygians, Galatians, Romans, Byzantines, Seljuk Turks, and Ottomans, and served as a trade center on the Silk Road.

Beypazarı

Close to sundown we arrived at our hotel, centrally located across from the town hall. We then enjoyed a short walk through town to a restaurant called Bağevi (Vineyard House) to feast on local specialties. Tarhana soup, made from sun-dried and sieved sheets of dough first kneaded with fresh tomatoes, yogurt, herbs, and spices, was delicious. Fresh grape leaves stuffed with ground lamb and rice and cooked with plum paste were not only tasty, but also the thinnest I had seen. The main course — lamb güveç, a rice casserole baked in an earthenware ot in a stone oven — lived up to its reputation. For dessert we had baklava, made from 80 thin layers of dough with walnut stuffing between every five layers and baked for four hours. Dinner was accompanied by a group of musicians and singers performing classical Turkish songs. The owner of the restaurant and his 84-year-old father took to the dance floor, while patrons clapped along. The only downside to this enjoyable evening was the cigarette smoke swirling above the tables.

For breakfast we walked over to the Taş Mektep (Stone Schoolhouse), built in the 19th century as a Koran school and now functioning as a restaurant. This two-story stone building is devoid of any ornamentation, with the exception of its many windows and wooden ceilings. Breakfast included fried eggs, tomatoes, cucumbers, yellow and feta cheeses, black and green olives, butter, honey, and flat loaves of local bread, accompanied by tea served in traditional clear, thin-bellied glasses.

The Yaşayan Müze (Living Museum) is the former home of a wealthy merchant and his wife, who was the town’s first woman teacher. In addition to traditional home furnishings, the museum features local handicrafts such as needlepoint, embroidery, jewelry, copperware, and woodcarving. Workshops in the arts of ebru (marbled paper) and shadow puppetry are also available to visitors.

Fulya enjoying

fresh carrot juice

Beypazarı consists largely of an open market, where one can walk about sampling local delicacies at vendor stalls — hardtack (kuru), walnut sausage with grape jelly, carrot delight, and jam. Beypazarı provides 60% of carrot production in Turkey, one sign of which is fresh carrot juice at many street corners for the equivalent of 25¢. Skipping lunch, we munched our way to the gold and silver market.

Gold and silver filigree embroidery, called telkari, is a famous Beypazarı handicraft passed down through generations of apprenticeship. Gold bullion is used as the raw material, and little pearls and red coral are sometimes used as accessories. Telkari is made by knitting very thin gold and silver wires into necklaces, bracelets, and belts. Such jewelry is sold by weight at reasonable prices. I bought a silver belt, as well as a silver piece worn over the hand like a glove with an open palm. The jewelry sold in the many small shops, stacked side by side, is all traditional; the technique goes back to 3000 BC Mesopotamia. Back on the bus at the end of a very full day, we returned to Istanbul, with stops in the towns of Mudurnu and Abant.