EASTERN TURKEY

May 2007

Eastern Turkey had always been on my wish list to visit because of its natural beauty and cultural richness. The opportunity arrived when a photographer friend familiar with the area offered to accompany me to this remote and less developed part of the country. We flew 1644 kilometers from Istanbul to Van, the major city in the east. A brief stopover in Ankara lengthened the trip to 2½ hours. The fact that there was minimal air traffic past Ankara on a cloudless day allowed us to fly low over the Anatolian Plateau to view the snow-capped mountains, the major GAP dam project, and finally Lake Van with its turquoise waters.

Meeting us at the airport in Van, our pre-arranged taxi driver took us to the centrally located Urartu Hotel, our base for five nights during our daily excursions to various parts of the region. Although we had offers from several locals to stay with them, we declined their hospitality in order to retain our independence. Turks are friendly people in general; yet hospitality is accentuated in the traditional east, where unexpected guests are considered to have been sent by God. People are quick to invite guests and will share whatever they happen to have, including food. This generosity is also characteristic of Kurds, who make up the majority of the region’s population. Our driver, himself Kurdish, was with us during our entire trip for a daily fee, in addition to which we paid for gas and lunch.

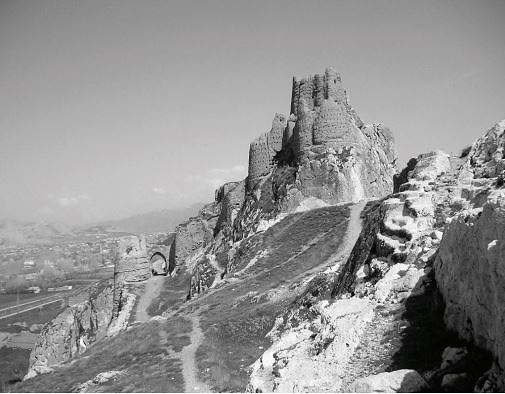

Van is located at an altitude of 1725 meters on the eastern shore of Lake Van, the world’s largest salt lake, 3760 square kilometers in size. Called “the sea” by the locals, the lake is ringed by snow-capped mountains that are covered with purple and yellow flowers in the spring. We were a little too early to witness this splendor, which can be seen from mid-May to mid-June. We began our sightseeing five kilometers from our hotel at the Citadel, which is built on a massive rock in old Van called Tushpa, the capital of the former Urartu Kingdom. Built in the 9th century BC, the Citadel features rock tombs and some of the oldest Urartian tablets, written in Assyrian cuneiform script. The view from the Citadel of the city below and of the sunset is worth the climb, which can take over an hour since paths are sparse and the nimbleness of a goat is required to negotiate the rocks.

Van Citadel

Inhabited by many civilizations since 4000 BC, Van, in addition to its longest residents, the Urartians, was home to Hittites, Hurians, and Persians, becoming the center of an Armenian kingdom in the 1st century BC. The series of occupations continued with Medes, Arabs, Seljuk Turks in the 11th century, Mongols in the 13th century, and finally Ottoman Turks, who defended the city from Persian attack in the 14th century. While the Citadel is the primary ancient ruin in old Van, nearby are two small mosques built by Sinan in the 16th century.

As we were photographing these stone gems, with their alternating stripes, we were invited by a Kurdish family to have tea. On a cloth spread on the emerald-green grass, we sat with the family — grandmother, son, wife, and two-year-old daughter — to enjoy home-baked goods and dates, accompanied by tea from their samovar. The tradition of tea drinking is an addiction in the east; people drink many glasses throughout the day. Our camaraderie led to an overnight invitation, which we kindly declined.

Returning to our hotel, we passed by a large sculpture of Van’s emblematic white cat, known for its eyes with half-blue and half-yellow irises. Indigenous to the city, these cats are known not to survive outside of their natural habitat. They are protected at a Cat House at the local University and may be seen by appointment. In the city center is a wrecked car suspended from a forklift truck. A large billboard next to the car reminds passers-by that “Accidents result not from fate, but from carelessness.” Driving by the harbor near a tea garden, we passed a shooting gallery of balloons floating on the water, a small local enterprise which my friend supported. Another impromptu stop by the roadside was at a Kurdish wedding party with music and line dancing, which we were welcome to photograph.

At the end of our long day we decided to eat at the hotel and indulged in its buffet spread. In this mountainous region, food consists more of meat and dairy products than of vegetables. Since Van is only 80 kilometers from Iran, there were Persian meatballs and imported watermelon among the selection. The dining room filled up with locals, who had made reservations to watch a soccer game between the country’s two main rival teams on a large screen. Soccer is a national passion in Turkey.

In the morning, after a buffet breakfast including local flat bread, white cheese with mountain herbs, and honey in the comb, we set out on a tour circling Lake Van — a circumference of 330 kilometers. We followed an inland road north and cleared a military checkpoint before turning in to the coastal road. Because of proximity to the Iranian border, IDs are checked to prevent smuggling of people, drugs, and cheap goods, especially gasoline, in case they slip by the border patrol. A highway billboard warned drivers, “The difference between 90 and 100 km/hour is the difference between life and death.” Nurseries of skinny poplars lined the coastal road, set against snow-capped, lush green mountains. Families enjoying a Sunday picnic, all with samovars, dotted the shoreline. Village houses and mosques with shiny aluminum roofs and domes to retain solar heat shimmered in the distance.

Our first stop was in the town of Adilcevaz at the Tuğrul Bey Mosque, from architect Sinan’s early period. As we were admiring its intricate geometric stonework, a busload of female Iranian tourists in black chadors arrived. On their way to Syria, they were going through Turkey to bypass Iraq. We continued to the town of Ahlat, known for the volcanic reddish-brown stone used in its buildings. There are over ten tombs made of this stone, some dating back to the 13th century. Most impressive is a Seljuk cemetery in an endless field of headstones, many over two meters high. Arranged 164 in rows, they create an incredible landscape of brown stones of varying shades with ornate bas-reliefs, making for a fascinating stroll.

Seljuk cemetery

The edges of Lake Van were increasingly full of brown silt from the mountains as we approached the town of Tatvan for a lunch break. We passed by an elementary boarding school for children from distant villages. At Tatvan harbor the car ferry, on its twice-weekly four-hour journey to Van, waited to load up with passengers from the Istanbul-Tehran train as seagulls fluttered above. We walked to a restaurant that specialized in buryani, lamb roasted slowly in a pit fire and served with pita bread. Amazed, I watched waiters call out orders for extra fatty roasts. In addition to what was already on our plates, large round loaves of pita came heaped in big baskets. The amount of bread our driver consumed was a reminder that this was the basic staple of the land.

The southern route from Lake Van to Gevaş was the most picturesque part of our trip. The road cut through the mountains to a landscape of black goats and white sheep on verdant slopes, mud houses on the hillside, and veins of ice turning into trickling streams under the glowing sun. We left the car in Gevaş and took a boat to the island of Ahtamar, where there is a 10th-century Armenian Church. The boat, which takes 25 minutes to reach the island, runs frequently, leaving when filled with passengers. The almond trees were in full bloom. The church, made of cut Ahlat stone, was a spectacle amidst the flowering white almond trees. The outside of the structure is decorated with designs and bas-reliefs of biblical figures such as Adam and Eve, David and Goliath, and Jonah. The interior has biblical frescoes. Built by king Gavuk I and completed in six years by stone masters, the building served as a church until the First World War. Now it is a restored historic site.

A Kurdish wedding party from northern Iraq arrived as we descended the steps to the boat for our return. A Kurdish bride is easily distinguished by the amount of gold she wears. The boat quickly filled with locals carrying big bundles of wild plants and herbs that they had gathered to use in cooking or making cheese. The island is an attractive recreation spot for picnicking and swimming. At the boat landing back in Gevaş, we stopped at the tea garden to keep our driver happy with the day’s obligatory refreshment. Nearby we visited the tomb of Halime Hatun, a must-see jewel because of its stonework. The last 43-kilometer stretch back to Van went quickly, without stops. Ready to settle in for the night, we ordered from the à-la-carte menu in the hotel dining room. I had a hearty red lentil soup; it was delicious.

The next day we explored the region south of Van, where there are two important citadels: Toprakkale (the Clay Fortress) in Çavuştepe near Gürpınar, and the Hoşap Citadel in Güzelsu, 25 and 60 kilometers from Van respectively. Çavuştepe (ancient Sardurihinili) was the second capital of the Urartu Kingdom in the 7th century BC. Only the fortress remains of what was once a major cultural center. The guardian provided information on details of Urartu life as revealed by excavations. The upper fortress had housed the king with his family and soldiers — about 2000 people. We walked about the temple, where sheep and cattle had been sacrificed, then viewed the kitchen, toilets, cistern, and underground wine and wheat cellars, which still have well preserved wheat of the time. The guardian is one of 38 people worldwide able to decipher Urartu cuneiform. He read one of the tablets, which said, “May those who deface this writing not be blessed by God.” He told us the Urartu language was related to modern Chechen.

The Hoşap Citadel was built in 1643 by Suleiman Mamudi, a Kurdish governor under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire. Güzelsu, on the highway to Hakkari, is a village where the road to Hoşap begins. There is a historic bridge by the same name before the turnoff. Made of stone arches, this is the oldest Ottoman bridge in eastern Turkey. We had tea at a sidewalk cafe near the bridge, before our car began its uphill climb. Like the Van Citadel, Hoşap appears to grow out of a large rock foundation, on which it is built. The outer fortress protects the castle, which has an impressive gate. Unfortunately, we were unable to go beyond the gate for reasons of security. There are a reception room, dungeon, mosque, and cistern within the outer walls. The view of the surrounding hills is spectacular. To enjoy the view there are benches and tables, where we chatted with boys in school uniforms playing hooky.

Back in the village we had lunch at a truck stop. Dry beans and rice were our choice, and naturally came with lots of bread. I was the only woman in the restaurant, and even outside on the street. Traveling with a smiling photographer who was used to striking up friendships, I felt welcome everywhere. Driving further south toward the town of Başkale, we had to clear several security checkpoints. Young high school graduates are assigned to such duty as part of military service, and are armed. Başkale seems to be a transit point for heroin smugglers originating in Afghanistan and making their way to Turkey through Iran.

The most rewarding part of the day was near Başkale in Yavuzlar, a village of 110 houses set against volcanic rock formations like giant sand dunes. Not yet on tourist maps, this geological wonder — gigantic sculptures shaped by nature that take on different moods with the shifting light — is a small version of Cappadocia. Mud houses plastered with dung faced velvety hills dimpled with melting snow. Young boys and girls herded their flocks, led by sheep dogs. Laundry fluttered against a backdrop of volcanic rock. Struck by the beauty of the setting while staring at poverty, I had mixed emotions about the inevitable discovery of this area by the tourism industry. Meanwhile, villagers earn a living by herding or by smuggling gasoline from Iran on horses, each carrying 40 barrels, over mountain tracks at night.

Of course we were invited for tea. Entering a five-room house, built by its Kurdish owners, we left our shoes at the door. The guest room, with a Persian rug, had cushions and folded blankets for seating along the perimeter. There was a gas stove, a TV in the corner, and framed Koranic verses on the walls. Spread on an oilcloth on the rug were two kinds of bread, yogurt, and cheese, all homemade. The women brought in the tea, and left after serving us. Our host, 70 years old, was a widower with three sons, one daughter, and three grandchildren. Their names reflected circumstances surrounding their births, such as Savaş (War) and Barış (Peace). All but one had Turkish names; the three-year-old granddaughter had a Kurdish name, Roja. One son was away on military duty. Although I was the only woman in a room full of men, and without head cover, I felt at ease chatting and complimented the food. The yogurt was the best I had ever tasted. We were invited to spend the night and our host offered to kill a sheep for us. To further underscore their healthy way of life, he said they burned dung instead of coal in the living room. We thanked our hosts for their generosity and said goodbye. Then we drove around the back to fill up with gas at the neighbors’ place.

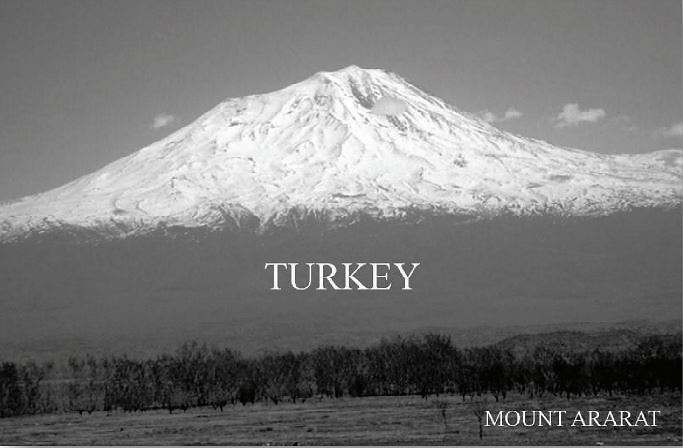

The next morning we headed north to Doğubeyazıt, Turkey’s easternmost city, 175 kilometers from Van and 32 kilometers from the Iranian frontier. The scenic road runs for a while between Lake Van on one side and green hills on the other, before turning inland toward Muradiye. In addition to grazing cattle, the hills are dotted with lookout towers to detect Kurdish militants, who are mostly active in the mountains. Clearing the routine checkpoints, we arrived at Muradiye Falls, which make a refreshing road stop. The falls ran forcefully, gaining strength from melting snow and forming a rainbow in the mist. A picturesque suspension bridge nearby added to the charm. We continued paralleling the mountain range that forms the Iranian border. At the Tendürek Pass we reached an altitude of 2644 meters. The landscape turned to red clay and pieces of black basalt rock. 40 kilometers from Doğubeyazıt, majestic Mount Ararat appeared covered in snow. We felt fortunate to witness its splendor without the usual cloud cover.

The Ararat mountain complex has two main peaks — Great Ararat, a dormant volcano 5165 meters above sea level, and Little Ararat, considered to be a spent volcano and 3896 meters high. Great Ararat, with its glacier peak, is one of the highest mountains in the world. The surrounding landscape is dominated by a ring of mountains all well over 3000 meters high. The earliest record of climbing Great Ararat is from an 1829 expedition in search of Noah’s Ark, which is believed to have run aground here. Many expeditions since then have failed to reveal any remains. Some speculate that Noah and his family may have broken up the ark to build their new home.

Due to security precautions it is difficult to obtain permission to climb the mountain. We were stopped while photographing it because we were near a military zone. Eventually we received permission from the commander, by requesting a soldier to accompany us and ensure our cameras pointed toward the mountain, away from the military zone. Later over rosehip tea, the commander explained that people posing as tourists had photographed the military compound, as confirmed by confiscated films.

A city of 56,000 people, Doğubeyazıt is a stopover on the busy international routes that pass through the region. Its markets are filled with mass-produced imports from Iran, Pakistan, and other eastern countries. For lunch we went to a place for döner kebap and ayran, a yogurt drink. Strolling through the arcades, my friend located a bottle of inexpensive cognac; I did not buy anything since there were no locally made crafts.

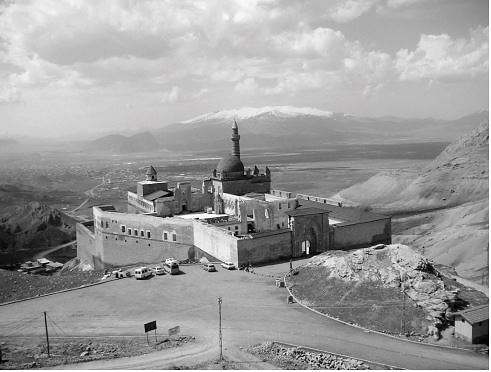

Ishak Pasha Palace

The major tourist attraction, located seven kilometers away from Doğubeyazıt, is the Ishak Pasha Palace, which rises up over the valley below. This noteworthy complex was built in the 17th century by Ishak Pasha, a Kurdish emir on whom the sultan had conferred the title of governor. This imposing structure controlled caravans on the old Silk Road, leading to an accumulation of wealth by its owners. Situated by an ancient Urartian fortification, the architecturally eclectic building of Persian, Seljuk, and Ottoman styles took 99 years to complete. Centered on two courtyards, it has 366 rooms, with a fireplace, an ornate mosque between the women’s and men’s quarters, and a ceremonial dining hall. The building was besieged by the Russian army five times, most recently in 1917, when its solid gold door was taken to Moscow. Although the palace has lost a great deal to pilfering soldiers, it is a treasure of carved stone. After a tea break with a splendid view and another round of photographs of Mount Ararat, we returned to Van.

Gold jewelry shop window

On our final day we visited a rug shop for Van’s renowned kilims, or flat-weave carpets, which are woven by Kurds. The shopkeeper identified several types — old ones made with natural root dyes and new ones with synthetic dyes. As he unfurled each one, he explained the stylized symbols, such as ram horn patterns. He was delighted to have us in the store, as business had been slow due to tourists’ fears of terrorism. I bought two carpets, a small and a large one, at very modest prices. We passed by a gold jewelry shop, gazing at the elaborate necklaces begging to be photographed. Our visit to a honey shop was unique; unlike the usual small, cluttered shops, this one was spacious and immaculate. Round tin cans of honey, arranged by flavor, were stacked on shelves along the walls; small towers of additional cans and jars sat on glass countertops. Bins on the floor designated an area for sampling. Once I tasted some of the honey in its natural comb, my decision as to what kind to buy was immediate. Although expensive, this honey was a rare find.

Living in a region of conflict has taken its toll on residents of cities near northern Iraq. Caught between the Turkish military and the Kurdish insurgents, many have resettled as refugees in Van, living in shanty towns on the outskirts of the city. At my request, our driver took us to the Mustafa Kemal Primary School in an outlying neighborhood. To assess the school’s needs we met with the principal, so that we might purchase essentials instead of giving cash. A visit to the kindergarten convinced us that the carpet remnants patched over the concrete floor needed replacing. There were hardly any toys around; a TV in the corner provided passive entertainment. We invited the teacher to go shopping with us, first for a carpet, then for toys. We placed a rush order for a wall-to-wall carpet, and had the teacher choose the toys, which were paid for by donations Turkish friends had given me to support a school. The teacher returned beaming to his classroom with bags of toys, a workbench, Lego blocks, hand puppets, plastic animals, balls, play-dough, books, and the like.

The next morning the principal invited us for one of Van’s famed breakfasts. At a sidewalk cafe we sampled dishes new to me — murtaba is made with flour, butter, and eggs; kavut is roasted wheat ground in a mortar and sautéed in butter. Fresh cream, honey, eggs with sausage, cheese, yogurt, and bread all crowded the table. To drink we had a glass of warm sheep’s milk, as well as tea. After breakfast we returned to the school to see the newly furnished kindergarten. The children had left their shoes at the door and were playing on the new carpet. One boy brought tools from the workbench to be included in the group photo.

On returning to Istanbul, I felt like I had visited a different country. This is a part of Turkey with deep cultural roots in the East, but awakening to the ways of the West as long-neglected modernity reaches the eastern frontiers. Hopefully traditions of hospitality and friendship will survive the rigors of modern times.

← Peru