AEGEAN COASTAL TOWNS

Çeşme Peninsula

October 2008

In the fall I had the good fortune to visit three friends with homes on the large Çeşme Peninsula, which extends out into the Aegean, to the west and south of Izmir. The area, known in antiquity as Ionia, took its name from the Ionian Greeks, who first settled along this coast and its offshore islands in around 1000 BC. The towns where my friends lived were, like many places in Turkey, near ancient sites. Three of the twelve Ionian city-states — Erythrae, Clazomenea, and Teos — are on this peninsula, where I spent a week in T-shirt weather.

It was convenient for me to go from Istanbul to Izmir by bus, since the departure terminal, on the Asian side of Istanbul, is not far from where I live. Likewise, the arrival terminal in Izmir was close to my destination in Çeşme, whereas traveling there from the airport would have meant an additional 20 kilometers. My overnight trip took seven hours, including a half-hour refreshment stop on the way. Privately run Turkish bus companies offer efficient, sanitary, and punctual service.

My friend Göksel met me in front of the old town hall in Alaçatı, where I was dropped off. A high school classmate and a former parliamentarian from Ankara, she has retired to this charming town on the Çeşme Peninsula. She lives in a restored old house with whitewashed stone walls and a second-story wooden bay window. We entered the house through a long, narrow hallway with high ceilings. Traditional benches with embroidered cushions lined the walls; hand-crocheted curtains hung in the long vertical windows. We climbed a wooden stairway to the second-floor receiving room, which opened onto a vestibule facing the bedrooms, all traditionally furnished with hand-woven textiles. Quickly leaving my bags, I descended to the living and dining room for breakfast.

The breakfast table displayed typical Turkish fare — feta cheese, olives, jams, sliced tomatoes and cucumbers, toast, and pita bread, served with many cups of hot tea. After breakfast and a short rest, we explored the town on foot. Alaçatı is an old town, with narrow cobblestone roads lined with small shops, cafes, and restaurants. The town center is closed to car traffic from 11 am to 3 am. Once a small, quiet town, Alaçatı has been discovered by both local and international visitors, who enjoy food, drink, and camaraderie within a quaint ambience till the early hours of the morning.

Alaçatı houses are built of white stone quarried in the region. The stones acquire a yellowish taint with age. The thick walls keep interiors warm in the winter and cool in the summer. Many of the houses, once built and occupied by Greeks who came to the area to work in the vineyards and olive orchards between 1850 and 1890, have deteriorated from neglect since the treaty on population exchange, following Turkey’s War of Independence. According to the treaty, Muslims in Greece were to move to Turkey and Orthodox Christians in Turkey to Greece, with the exception of Greeks in Istanbul and Turks in Western Thrace; overall 2 million people were displaced from their homes. In recent years many of the abandoned homes have been restored, either as private residences or as small hotels.

Street in Alaçatı

Göksel and I walked through the town center to the landmark old windmills on the highest hill. These windmills in stone were built in the late 19th century to grind flour, and now grace the landscape as reminders of bygone days. On the way I noticed a shop with colorful displays of soap molded to look like fruit, from grapes to bananas, and placed in bins. Charmed by the novelty, I decided to come back later to buy a basket of “peaches” and “pears.” We continued our walk, following signs to an arts and crafts gallery, where we watched a ceramics class for children and bought one-of-a-kind textiles.

In the evening we drove to a fish restaurant in Ilıca, a resort town known for its thermal springs. At a restaurant called Yusuf’s Place, we enjoyed turbot and salad, preceded by cold and warm appetizers, such as marinated dried tomatoes, sardines, fried eggplant and peppers with yogurt, and squid. Although full, we complied with the Turkish tradition of finishing a fish meal with halvah to aid digestion. When we returned to Alaçatı at around 11 pm, the streets were filled with people. Vendors crowded the sidewalks with big steaming kettles of corn on the cob; cafes and pudding shops attracted passers-by with mastic-flavored specialties, including coffee. Gum mastic is plentiful in the region; much of it comes from the Greek island of Chios, 400 meters from the shore.

The next day was the first of a three-day bayram, a religious holiday following Ramadan and called “Candy Festival” in Turkish, because of the tradition of offering sweets to friends and relatives who visit. We were invited for breakfast at the Sesil Hotel, whose owner was a friend of Göksel’s. The spread, which would easily qualify as brunch, included homemade pastries, eggs, and a variety of cheeses, jams, and breads, accompanied by tea. The extensive meal ended with baklava, coffee, and sour cherry liqueur. I was able to see a few of the unoccupied rooms, where elegant furnishings were for sale to customers wishing to purchase them at the end of their stay. My take was a bag of homemade noodles, courtesy of the hotel’s owner and manager. As we stepped out to the street, we were greeted by a drummer, who played for us cheerfully in return for bayram tips.

Following lunch, yes, we ate again. We then went for a drive along the shore at the western end of the peninsula, all the way to Dalyanköy (Fish Trap Village) at the tip. On the way we stopped to admire beautiful homes, some with aquariums running the length of the sidewalk for the pleasure of passers-by. In Çiftlik Köy (Farm Village), we paid a bayram visit to a friend, whose garden with its water view was a delightful stopping place to sample an assortment of sweets.

Back in Alaçatı we were welcomed by the mayor, who was enjoying tea in front of a bookstore with the owner. As a respected year-round resident, Göksel seemed to know everyone whenever we walked about; the mayor was no exception. Pointing to two stools, he asked us to join him for tea. I later found out that he had banned plastic chairs in food establishments to help maintain the town’s historic character.

The next morning I went up to the roof terrace of the house to enjoy the surrounding view. The panorama was an endorsement for the picturesque town. A cluster of white buildings with red tiled roofs could be seen nestled against low hills in the distance; a minaret pierced through olive trees. Nearby, ripe red pomegranates beckoned to be picked. I descended to the garden to pick a few big ones to carry to Istanbul.

Ülkü — another high school classmate, who spends summers with her daughter in Alaçatı — joined us for breakfast. I went home with her to stay for the next four days. Ülkü’s place, built by her Italian son-in-law, was a modern version of an Alaçatı house with its thick whitewashed walls. Blue wooden shutters decorated the walls of the single-storied house, revealing flower pots in the recessed windows. The rooms lined both sides of a long corridor featuring skylight windows. Located on a quiet back street, the house opened onto a patio with a built-in fireplace and an olive tree. The interior decor reflected the simplicity of the architectural design, with sparsely placed contemporary furniture.

An exploration of the back streets of Alaçatı revealed beautifully renovated 19th-century homes, boutique hotels with pools and quiet courtyards, as well as cafes and restaurants under grape arbors or olive trees. After a break for mastic-flavored coffee, we strolled on to the antique market. In the town center, closed to all traffic but motorcycles, vendors had set up stalls in designated areas. Open every day, the market offered a mixture of second-hand goods and local crafts. I bought a light blue tablecloth with traditional black motifs, printed using a stone block.

Making gözleme

The next day we drove to the town of Şifne on the northern coast of the peninsula. The Thermal Hotel, facing the beach, provided deep and shallow hot pools, in addition to an indoor one for physical therapy. After a dip in the Aegean, which is very salty for swimming without goggles, we jumped into the thermal pool, which was 42º C. Feeling refreshed, we continued our drive, passing fancy homes to Pasha Harbor. We then traveled east on the coastal road, arriving in Ildırı (ancient Erithrai), a picturesque fishing village. We passed by fishermen mending nets, and settled in at the Manzara Kahvesi (Scenic Coffee House) to view the sunset. As the sun disappeared behind boats, islands, clouds, and mountains, leaving spectacular streaks in the dimming sky, we enjoyed gözleme, a pastry filled with feta cheese and herbs and cooked on sheet iron. For desert we had lokma, small balls of fried dough dipped in syrup, with tea.

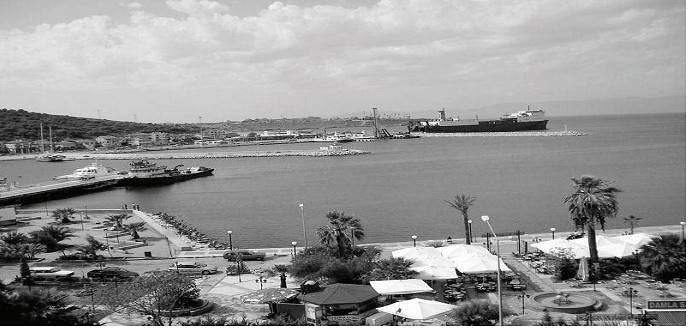

Another excursion was to Çeşme, a busy port and resort at the western end of the peninsula. The town looks out towards the Greek island of Chios, to which there is a regular ferry service. The port at Çeşme is dominated by a Genoese fortress from the late 13th century, an impressive structure with a towered citadel surrounded by a double line of defense walls. Çeşme also has two 17th-century mosques. Walking through the market, we stopped for mastic-flavored ice cream, and then went into a sweet shop to purchase jam made from the region’s famed small green figs.

Ülkü was keen on my tasting other local Aegean specialties. On our way home we ate at Şevki’s Place, a restaurant known for a local dish called kumru. The name means “turtledove,” but the dish actually looks like a small pizza with sausage, cheese, and tomatoes. We also had çığırtma, charred eggplant cooked in olive oil with garlic and tomatoes.

My final day in Alaçatı coincided with the Saturday farmers’ market, which offered clothing and household goods at very modest prices, in addition to local produce. Wending my way through a riot of color and noise, I purchased items ranging from Kalamata olives and dried sour cherries to bath and kitchen towels, cushion covers, a pair of pants, and a shirt.

Afterwards, not to miss out on Alaçatı’s renowned windsurfing bay, we headed out four kilometers from the town center. A wind farm stretched ahead on the slopes of a hill. Turbines, placed facing strong winds, stood 50 meters high from the ground, waiting for the wind to accelerate. Once the wind speed reaches 25 meters per second and the long blades of the turbines are turning at a speed of 29 rotations per minute, electrical energy begins to be produced. Alaçatı has set an example for similar investments in other cities.

The bay is lined with windsurfing clubs and surfing schools, because of favorable wind conditions most of the year. However, business had slowed down with the start of the school year, and many of the clubs were closing until the spring. Over a cup of tea in one of the clubs, we watched a few windsurfers on the water, while surrounded by the youthful energy of others on the terrace.

The following morning Ülkü drove me to my next destination, Zeytinalan, a village outside Urla, which is the oldest town on the peninsula west of Izmir. However, we did not pass up the opportunity to have breakfast in the Tepe Coffee House in Zeytinler, famous for its village breakfast, which included black mulberry jam, clotted cream, honey, assorted olives, and bread straight from the oven. The Turkish word for “olive” is zeytin; many places in the region are named after this bountiful fruit.

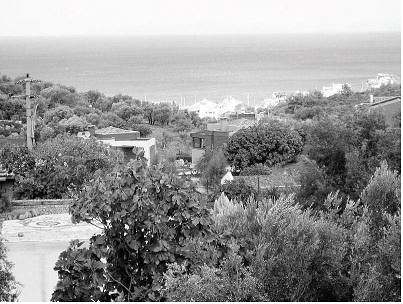

View over Zeytinalan

My friends Evin and Mick McCain live in a contemporary housing development on a hill overlooking the Aegean in Zeytinalan, outside of Urla. To arrive there we drove up winding roads, passing custom-built homes secluded amidst fig and olive trees. Evin met us at the gate and led us to the top level of her two-story house, built against the crest of a hill. Instantly, I was drawn to the sweeping view outside the large picture windows. The azure waters of the Aegean shimmered in the distance; a family gathered olives off the ground nearby. Then my gaze turned to the interior furnishings. The house was a treasure trove of folk art from throughout Anatolia, collected during my hosts’ respective travels — Evin as a tour guide and Mick as an American missionary and teacher since the late 50s. The kilims were enticing.

Evin had lunch ready. Customarily Turks have two cooked meals a day. An olive motif on the tablecloth and matching napkins was a reminder of the importance of this fruit in the region, where cutting down an olive tree is punishable by law, and an olive tree is priced separately from the land it occupies. A platter of large artichoke hearts with their stems took center stage on the table, along with dishes of mixed olives and sliced tomatoes and cucumbers. Cooked in olive oil with fresh dill and eaten cold, the artichoke dish preceded dessert, which was melon. Grilled chicken chops, homemade noodles, and green beans followed the initial soup course — a typical order in Turkish cuisine, where a hot meal is often followed by cold olive oil dishes. A serving of fruit generally precedes optional coffee.

During my two-day stay in the region of Urla we explored several ancient sites, beginning with the closest one, the Ionian city of Clazomenea. Most of the artifacts found here have gone to the Archeological Museum in Izmir. However, a most interesting aspect of this visit was a museum of local olive oil production, which dates back to 600 BC. Digs in 2005 revealed an entire industry, including wells carved into rocks for making and storing oil in a zone outside the city walls. With expert help from local builders, replicas of tools have been made into a museum, where visitors learn about olive oil production, an industry which depended on manual labor before mechanization. Large mill stones crush olives into a paste, which goes into sacks made of goat hair. A heavy stone is lowered over the stack of sacks, pressing out the oil along with the olive’s dark juice, which fills two stone wells half-filled with water. Adding hot water helps to float the oil, which is then skimmed into a third well to settle before it is bottled. Oil from this first pressing is known as “cold-pressed oil.” Plans are underway to create a child-size version of the museum, where children will arrive with their own olives and process them into oil.

The Çeşme Peninsula is very fertile. Before returning home we went to the farmers’ market, where Evin, as a regular, seemed to know most of the vendors. While she stocked up on fruits and vegetables grown in the region, I enjoyed walking amidst mounds of grapes, melons, pomegranates, black and green figs, fresh black-eyed peas, and many edible herbs and weeds, in addition to strings of dry tomatoes and red peppers hanging from the stalls.

Also rich in fishing, the coast boasts numerous fish restaurants. For our evening meal we patronized one at the harbor, owned by Evin’s son. Here we enjoyed grilled sea bream, preceded by assorted appetizers of grilled and fried squid, fava (mashed broad beans), fresh black-eyed peas, and arugula. Dessert was a choice of mastic-flavored pudding or ice cream roll coated with dried figs, in addition to black grapes.

The next morning we drove to Urla, the oldest town on the peninsula, with a population of 41,000. Many of the houses, formerly owned by Greeks, have not been restored, give the town an aging veneer. The town has three mosques from the late 15th century and an ablution fountain with a domed ceiling, painted in the 17th century. An old summer resort for Izmir residents, Urla has in recent years lost some of its seasonal population to swinging Alaçatı, which tends to attract young people.

Later on we drove to Izmir, the former Greek city of Smyrna, which is Turkey’s third largest city after Istanbul and Ankara, and the most important harbor on the Aegean. We started out on the hill where Smyrna is thought to have been founded by Alexander the Great, King of Macedon, in the late 4th century BC. A small part of the city was then located on the hill, while the larger part was located on the flat terrain near the harbor. Excavations have revealed traces of the city structures, including the Agora on the hill, where we spent most of our afternoon until closing time at 5 pm.

The Agora, which served as the administrative, political, judicial and commercial center, covers a rectangular area measuring 120 by 80 meters. Basements built to eliminate the gradient of the terrain are held up by arches, which support an elevated courtyard covered with stone slabs and surrounded by porticos (columned galleries). A row of Corinthian columns from the ground floor of the western portico has been restored and erected, along with a double-arched gate. The keystone of the northern arch has a bust of Faustina, wife of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, who restored Smyrna after an earthquake in 178 AD.

The Basilica, which served as a trade center, is located on the northern side of the Agora. Two floors, built over a basement of four galleries, sit on a structure supported by arches. The rectangular ground plan is divided into three galleries by rows of columns; the middle gallery is wider and higher than those on the sides. Though the full structure of the basilica and portions of the western and eastern porticos have been exposed, totally uncovering this ancient site, part of which is currently under a park, appears a monumental task. First used in the Hellenistic period, the Agora functioned as a cemetery during the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, as evidenced from the cluster of tombstones on the grounds. The white marble Ottoman headstones feature different turban styles, indicating the rank and profession of the deceased.

With Evin and Mick

After we descended to flat terrain, my friends wanted to show me other parts of Izmir. Evin and I walked through the old Jewish quarter to the Kızlarağası Han, an Ottoman commercial structure, where we ambled along a stretch of jewelry, embroidery, and textile shops. We had tea in the courtyard of the han, and then walked to the Kordon, Izmir’s attractive seaside promenade, ending at the pier with a stroll through the mall, which was lined with luxury shops. Across the way modern apartment buildings with air-conditioning units on every floor shared the urban landscape with Ottoman architecture.

For dinner we went to a restaurant called 1888, where we met up with some of Evin’s friends, also guides. They all shared a passion for classical antiquity and met regularly, taking turns giving in-depth introductions to various topics. This night, however, was an exception, as Evin had guests. Following a variety of cold and warm appetizers, we had çöp kuyu kebap, skewered meat cooked slowly in a pit oven and served on a bed of onions with cumin and black pepper on the side. Listed on the menu in English as “Aegean-style kebab,” this dish was the house specialty. Though usually abstaining from red meat, I break all rules in Turkey, which some consider to have one of the world’s best cuisines. We finished the meal with a sweet made of figs.

The last Ionian city we visited before my departure was Teos. Some of the recently excavated sites here include the Hellenic Wall and the stage of the main Amphitheatre. In the center of the archeological site is the Temple to Dionysus, the most famous edifice in Teos. Under the protection of Dionysus, patron saint of drama, the Artists of Dionysus, a professional guild of actors and musicians who supplied performers for hire at festivals all over the Greek world, enjoyed universal privileges, such as freedom from taxation and military service. Rich in culture, the city became known as a trading center for fine arts and crafts.

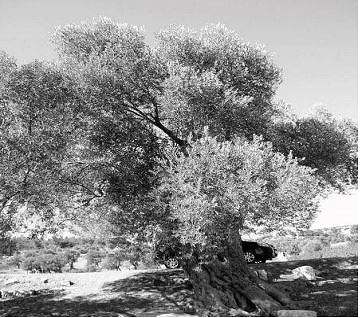

The caretaker of the historic ruins shed light on the very slow process of excavation. Most of the land around is covered with olive orchards, which are privately owned; even if owners are willing to sell their property, they will not sell their olive trees. A sustained budget is needed to attract trained people to work on the digs; government funding lasts a couple of weeks at a time. Archeologists and students on the digs are tied to the academic calendar and are, therefore, only able to work on site during the summer, which is also the hottest time of the year. We walked around the temple, which had separate channels for water and wine. Large pieces of stone were connected by iron bars, held in place by poured lead. I wished that the ancient, majestic olive tree on the site could recount history.

Majestic olive tree in Teos

At the northern part of Teos is Sığacık, a pretty little seaside town with a Genoese fortress from the late 13th century dominating the port. Fishermen’s boats mingle with private yachts in the harbor. The town’s winter population of 17,000 grows to 150,000 during the summer. Old houses in back streets give way to fancy residences on the hill. We settled down at an outdoor family-owned restaurant, where we enjoyed mantı, Turkish ravioli served with garlic-flavored yogurt.

Evin and Mick drove me to the bus terminal, where I boarded the bus back to Istanbul. As I parted, I thanked my friends for the two culturally rich days I had spent with them. Evin encouraged me to come back to see Sardis, ancient capital of Lydia, 43 kilometers east of Izmir. I promised I would return!