MEDITERRANEAN REGION

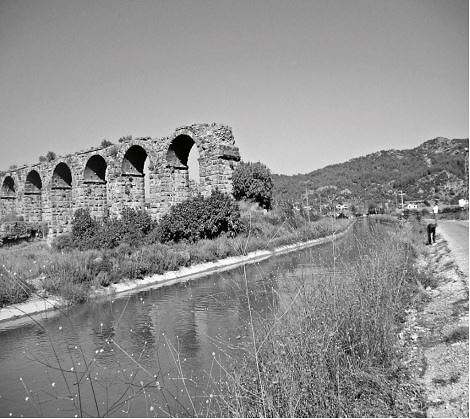

Roman aqueduct

Crossing the Toros Mountains (2400-2600 meters high), we came to a rest stop at Zirve (the “Peak”), where we enjoyed lunch with a panoramic view. The rocky side of the mountain gave way to lush green land below with cedar, cypress, oak, and poplar trees. A souvenir shop carried local honey from the high plateau, as well as pottery and onyx stoneware from nearby towns. My lucky find here was a translucent onyx bowl at a very modest price. Often these items command high prices in big city markets.

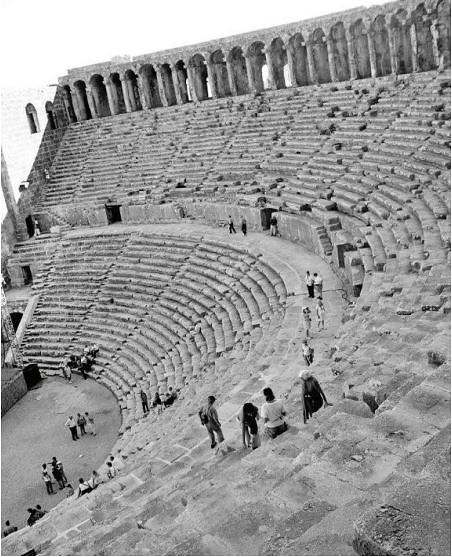

Aspendos Roman theater

Heading south to the Mediterranean flatland, we passed by olive and palm trees; vendors sold bananas and citrus fruit by the roadside. Heaps of dry sesame plants awaited a beating to let go of their seeds. We passed by the Manavgat River and a 2nd-century AD aqueduct amidst wild blackberries and cotton fields, arriving at Aspendos, one of the world’s best preserved Roman theaters. I climbed to the highest of the 40 rows surrounded by a vaulted gallery, and sat down as a spectator in this 15,000-seat theater. Quickly drawn to the time of Emperor Marcus Aurelius Roman aqueduct (161-180 AD), I looked down upon the stage, imagining the actors in this acoustically perfect setting. There was a statue of Dionysus, patron god of the theater, at the base of the stage. However, it was disconcerting to see metal scaffolding with myriads of lights angled to the stage for the amplified pop concerts that are now held here for twice the number of people — a thoughtless contribution to the deterioration of antiquities.

Following the coastal road to Antalya, we drove by hothouses, tented markets, houses with flat rooftops, and satellite dishes on balconies. Hotels, holiday villages, car dealers, and jewelry shops beckoned both local and international tourists. Ready for a taste of the Turkish Riviera, we pulled up at the Khan Hotel.

Antalya is a city of dramatic grandeur nestled at the northern end of a gulf against the high Beydağları (or Lycian Mountains). Founded by Attalus II, King of Pergamum, between 160 and 139 BC, Attalia was given to Rome by Attalus III, thus becoming a province of Pamphylia. It became part of the Ottoman Empire in the late 14th century. Because of its proximity to both mountain and sea, modern Antalya, with a population of 600,000, is a popular resort with a wealth of history. Antiquities such as Hadrian’s Gate and fragments of old walls running through the city enhance its charm.

Our first expedition in the region was to Perge, a Roman town 18 kilometers east of Antalya. Village women displaying crafts lined the road to the stadium. A turquoise crocheted hat with colorful beaded braids seemed a perfect gift for my granddaughter Iris. Scarves with hand-embroidered edgings rose above the usual tourist wares. We walked about the vast stadium, the baths, and the agora (marketplace), learning about the customs and history that have been brought to light by excavations.

Returning to the picturesque harbor quay, lined with date palms, flowerbeds, benches under shady trees, and luxury apartments with a water view dotted by sailboats, we arrived at the Antalya Museum. Items dating from the Neolithic age, starting with sea fossils, can be found here. One walks through history, encountering such treasures as earthenware tombs, Hellenistic jewelry, coins, statues of classical gods and goddesses (such as Athena and Aphrodite), and a sarcophagus of Alexander the Great. Archeologists, both Turkish and international, who have headed the various digs, are honored with pictures and biographies. Some items have been smuggled out. After five years of litigation, the Brooklyn and Getty Museums have returned stolen sarcophagi. Negotiations with the Dumbarton Oaks Museum are ongoing.

The ethnographic section of the museum features a typical Antalya home with its living room, bedroom, and bathrooms. On display are old carpets, embroidery, and jewelry. The museum has a government-run gift shop with high-quality goods. A shallow fish-shaped copper pan I purchased here was worth carrying its weight. The rich experience of the morning continued over lunch with a local specialty — grilled sea bream accompanied by olive oil and lemon dressing and sprigs of arugula on the side. Purslane salad and a mixed fruit plate of melons, grapes, and plums were the best produce we had sampled so far.

Döşemealtı, a region 20 kilometers north of Antalya, is famous for its carpets. We decided to head north to see them. Driving alongside pomegranate and orange trees, we spotted a wholesale carpet shop. The owner was out collecting carpets from the villages. His wife and daughter welcomed us and began unfurling their inventory, as Evin explained the symbolism of their stylized eagle and spider motifs. According to Islamic belief, it was a spider that saved Mohammed’s life, which is why the spider is often used as a holy motif. A ground of deep red characterizes these carpets, with patterns worked in dark blues and tans. The center commonly contains a medallion, often a spider. Since these carpets had not yet found their way to retail shops, we were able to purchase a few at very reasonable prices.

The following day we walked through the old city to board an excursion boat for a tour of the old harbor. The sea view of modern Antalya rising behind ancient walls was compelling. To the west, spectacular mountains with waterfalls rose straight from the sea. We weighed anchor near a small uninhabited island and swam in the clear emerald waters of the Mediterranean. I was delighted to find that my muscles still remembered how to dive headfirst, an activity I had not tried since my teens. Our captain, who was also our cook, fixed us a delectable lunch — fresh-caught mackerel, pasta, season salad, and watermelon. Afterwards the boat moved to another spot, anchoring near a cave. We dove in again to explore the cave.

Early the next day we left Antalya, heading west toward Denizli. We drove through pine forests and the Taurus Mountains, to fertile valleys with figs and tobacco plants. Black goat-hair nomadic tents dotted the mountain pastures. Slogans to protect the forests lined the mountainside. We passed marble quarries resulting from geological wonders when central and western Anatolia used to be under water. Calcium deposits at the bottom of the warm waters hardened into marble with the drying of the oceans, their color and vein structure determined by fossils and mineral elements.

Melon stands by the road and fields of tobacco stalks were signposts of the fertile land. Tobacco leaves are handpicked early in the morning and left to dry, strung on strings tied to bamboo poles. Another common site was the plant of the chickpea, a popular snack in Turkey once harvested and roasted. At the road sign to Pamukkale we turned north.

Pamukkale (the Cotton Fortress), founded in the 2nd century BC, served as the spa city Hierapolis in Roman times. The wondrous lime and other mineral deposits, solidified upon contact with the air, have formed terraces of white travertine (a form of limestone) as rivulets of hot water bubbling up along the edge of the mountain spill over them. Many tourists are attracted to the curative power of the town’s waters, combined with its well preserved ruins. The Ministry of Tourism no longer allows any hotels to be built near the travertine formations. A hotel with a terrace overlooking the crystalline landscape, where I stayed in 1964, is now gone.

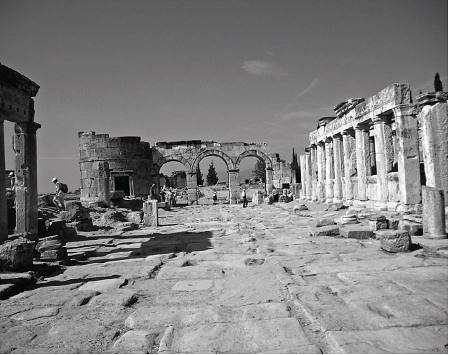

Hierapolis

The grounds of Hierapolis included the necropolis, which housed tombs of families. Lighter-colored sarcophagi (the word in Greek means flesh-consuming stone,” referring to their chemistry) indicated recent excavations. Next were the baths, later used as a Christian basilica, and the main street of huge stones. The agora was lined with shops, with lion gates at each end. The Archeology Museum displayed treasures from the prehistoric and Roman digs — pottery, coins, gold jewelry, and many statues. A visit to the Roman theater ended our tour.

Delighted with the opportunity to experience the shallow waters of the travertine terraces, we walked about, pants rolled up and shoes in hand, admiring rippled patterns on slippery stones. Following a refreshment of freshly squeezed pomegranate juice, we headed to our hotel to enjoy its hot tub and a welcome swim in the pool. The attraction of the dinner was watching village women make gözleme, by rolling out thin sheets of dough, which they layered with chopped spinach or meat with herbs, and cooked on a sheet of iron over a wood fire.