BLACK SEA COAST

A 7 am flight took us from Istanbul to Trabzon. After a 90-minute trip we landed in Trabzon, a town on the Black Sea coast which was once the seat of the Trebizond Empire, founded in 1204 by Alexius Comnenus. It was clear and sunny — a perfect day to visit the Sumela Monastery in the mountains, 54 kilometers south of Trabzon.

We drove through pine forests and hazelnut groves to reach the steep stairs of the monastery, set against the rocks and now situated within a national park. We viewed frescoes as we climbed up to the buildings against the sheer cliff, and admired the grand panorama.

Our lunch on the mountain featured local specialties such as black cabbage soup, stuffed black cabbage, and a Turkish fondue known as huymak, which is eaten with chunks of bread dipped in melted butter, cheese, and cornmeal, followed by grilled trout.

Descending from the mountain, we passed by fish farms and houses bunched around patches of farmland. People isolated in this rocky terrain are of Greek descent and still speak an archaic form of Greek.

There is another Haghia Sophia church in Trabzon, built by the Greeks after the one lost with the fall of Constantinople. Also later converted to a mosque, this church is now a museum set within a well kept garden near the coast. Finally back at our hotel, we called it a day as seagulls hovered overhead, and people rushing home for iftar deserted the streets.

Our second day in Trabzon began with a visit to the Trabzon Museum, the restored mansion of a former Russian merchant. The upper floor features the ethnology of the region, the lower one its archeology with objects from various Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman digs. The garden, restored to its original state along with the mansion, is filled with dahlias, roses, and date palms.

Another museum in Trabzon is Atatürk’s house, the former summer home of a Greek banker on a hill reached by a winding road. Surrounded by roses, the bust of the founder of the Turkish Republic sits on a base engraved with a proverb: “A nation’s inspiration and strength come from its soul, not from its riches.” Given to Atatürk as a gift by the municipality, this house is where he wrote his will, leaving all he owned to the Turkish Treasury. Among his memorabilia are letters telling how free he felt and how much more he wished to leave to the nation.

We continued on to the mountain resort of Uzun Göl (“Long Lake”) for lunch, passing by tea plants on terraced hills. The best yield of the low-lying plants is the shoots and the top two layers of the leaves. Once harvested, these go to a factory for processing. The time of the harvest determines the color of the leaves, which range from green to black. Hazelnut trees also like the warm, humid climate of the Black Sea region, and grow densely on its steep hills. Harvesters with baskets on their backs tie themselves to the trees. Turkey is the largest exporter of hazelnuts in the world.

At lunch we enjoyed specialties such as red lentil soup, Ezo gelin (“bride Ezo’s soup”), and stir-fried lamb with wild thyme. The unique breadbaskets at the table caught my attention. Upon my inquiry as to where I could buy such a basket, the proprietor presented me with one as a gift. Since we were at a mountain resort off-season, shops were closed. However, the owner of one was fetched for us. I was able to buy a square of a hand-woven cotton cloth typical of the region, with alternating black and red stripes in decreasing thickness on a white background.

Upon returning to the city a few of us rushed to Kemer Altı, the old bazaar, as shops tend to close early during Ramadan. Some were already pulling their shutters down. We passed by gold shops and stopped to see local fabrics. I was glad to find a similar piece to the one I had purchased earlier — this one a large rectangle, the perfect size for a tablecloth.

Our bus headed west, following the rocky coastline with its occasional fishermen’s coves. Piers constructed of big boulders jutted out into the sea. We passed by women with bags tied to their waists collecting tea leaves with special scissors. Hazelnuts in their green outer shells spread out to dry filled patches of flat land. Corn husks tied together formed miniature teepees.

We stopped by the roadside to stock up on produce from the region and to wet our feet in the Black Sea. We returned to the bus with bags of tea, roasted hazelnuts, and jars of hazelnut butter. The highlight of our roadside lunch was carrot cake, which was on the house. Made with semolina, carrots, sugar, hazelnuts, and cinnamon, this treat was topped with ice cream.

After Istanbul the Black Sea coast is the most populated region in Turkey, with towns almost running into one another. The country’s boat building, coal, tobacco, and rice industries are all in these coastal towns. We turned south near Samsun and took the inland road to Amasya. The landscape changed from lush green hills to flat fertile land with cows grazing. Sacks of onions waiting to be transported dotted the fields.

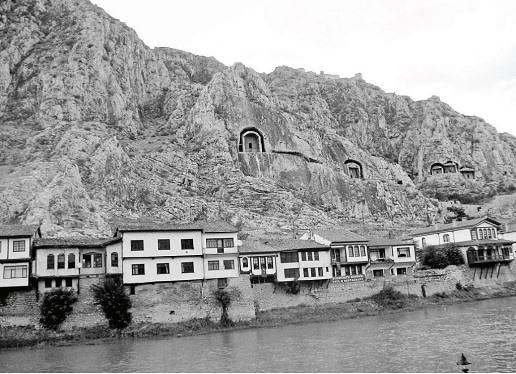

A picture book city, Amasya sits astride the Yeşilırmak (or Iris River) in the mountainous region bordering the Black Sea. It was the capital, Amaseia, of the Pontus Kings during Greek and Roman times. A citadel and Pontic cave tombs on the hill, as well as houses overhanging the river, enhance the city’s charm.

Hillside cave tombs and houses in Amasya

At the Amasya Museum, the upstairs, dedicated to the Ottoman ethnology of the region, displays a woman weaver at a loom, textiles, and embroidered bridal dresses, recalling the city’s fame for silk manufacturing. The street level has archeological artifacts, including mummies brushed with a preservative that has kept the whole bodies intact, unlike Egyptian ones, from which the eyes and other organs are removed. Roman marble columns fill the garden.

The Gök Medrese and Mosque, built in 1266, is a typical Seljuk building with carved stonework and tiles featuring angular geometric patterns. The Sultan Bayezit II Mosque, built by the son of Mehmet, the conqueror of Istanbul, in 1486, still has an active soup kitchen, where a long line of people were waiting to enter the green-tented area nearby to end their fast.

The Amasya Hotel, where we stayed, is strategically located facing the river. I spent the evening with Connie and her daughter Margaret on the balcony playing backgammon on their newly acquired inlaid set. I was sound asleep when cannons announcing sahur (the pre-dawn meal) awoke me. The preferred time for sahur is the last half-hour before dawn, after which fasting begins again until sunset. I had just gone back to sleep when roosters began crowing, as if they knew we had a long journey ahead.

Breakfast featured a local specialty, keşkek, made with chick peas, wheat, and meat. Other offerings on the buffet included Amasya’s famous sweet crisp apples, tahini halva, yogurt, honey, feta cheese, olives, tomatoes, cucumbers, and a variety of bread. On the way out of town we stopped by a roadside stand stacked with apples and pears, and stocked up for our trip to the heartland, the Central Anatolian Plateau.

On the bus Evin gave us a short history lesson. During World War I Mustafa Kemal, then a general in the Ottoman army, met with Anatolian town leaders in Amasya, where they promised to give all they could to fight the Allied forces on the occupied fronts, which were basically all the country’s shores — Russia to the north; British, Australian, and New Zealand armies in Gallipoli to protect entry into Istanbul from the Dardanelles; Greeks to the west; Italians to the south; and French to the southeast. The longest conflict was the three-year war with the Greeks, who dreamed of reestablishing the ancient Greek Empire in Anatolia. In 1922 the Greeks were driven out of Anatolia; the rest of the occupying forces withdrew, accepting Turkish victory.

Mustafa Kemal, who was given the name Atatürk (“Father of the Turks”), abolished the Ottoman Sultanate, established a parliament, and founded the Republic of Turkey in 1923. In 1924 he abolished the Islamic Caliphate and began a series of reforms. Swiss civil law replaced Islamic sharia, Western-style dress brought greater equality in appearance, school reform introduced compulsory education, the Latin alphabet replaced the Ottoman script, and women became entitled to vote and eligible to serve in Parliament. All these reforms became law during the 15 years of Atatürk’s presidency.

Among the many roadside billboards we saw advertising consumer goods, there was one paying tribute to history: “There is no nation without those who have died in war.” As we continued southward on the excellent road, I was reminded of a very bumpy ride I had taken over muddy ruts across the same terrain in 1964. The transformation of the Central Plateau was amazing, not only in its roads, but also in the giant industries that had cropped up everywhere — Fiat, VW, and Toyota car dealerships; grain, nut, and dry fruit factories; sugar plants; and chicken farms alternated with vast fields of wheat. Tractors had replaced oxcarts. Much to my delight, strong infrastructure was in place; the visible poverty of the heartland was no more.

← Turkey (1) (main page)