AEGEAN REGION

We continued our itinerary through the Aegean region toward the town of Aydın. The landscape changed to cotton fields dotted with tents of migrant workers, who had come from other parts of Anatolia to pick cotton before the rains started. Cotton is still picked by hand on small farms. Women in colorful headscarves and baggy pants bent over the fields composed a beautiful rural tableau, despite their backbreaking work. Advertisements for thermal baths, hotels, marble, and travertine highlighted the contrast in wealth.

Sarcophagi at Aphrodisias

Crossing a tributary of the Menderes (Meander) River, we turned off onto a village road toward the ancient city of Aphrodisias, driving by many reeds, which signaled the moisture of the area. The early inhabitants of Aphrodisias lived in caves and formed matriarchal societies. Having babies was important to assure the survival of the tribe. Idols were female from very early on until about 1000 BC, when male power gained importance in farming and wars. Aphrodite, the city’s patron goddess, symbolized fertility in the Greek and Roman periods.

A village had been built on the ruins of the ancient city, now under water. In order to excavate, people had been relocated to a new village, and the water pumped to dig out the ancient city. Temples; a house around a courtyard; a theater; a stadium; a council chamber; and separate baths for cold, tepid, and hot water have been uncovered at Aphrodisias. The Aphrodias Museum has attractive statues, including ones of Apollo and Aphrodite; the many levels of the structure represent the universe, from the heavens to the underworld.

The village square has a giant sycamore tree, an Ottoman fountain, and marble antiquities. Ionian column heads, benches with carved dolphin arms, and sarcophagi with masks in high relief are the backdrop for a coffee shop. People carry on with their daily lives, respecting the setting. We enjoyed lunch overlooking lush grapes. Upon request I walked away with one of the garlands of dried red peppers adorning the rafters of the restaurant. Cotton tablecloths, hand-woven by the villagers, were beautiful in their simplicity.

Back on the main road we passed by fig processing factories near Nazilli and newly planted strawberries in Sultanhisar, then switched to a scenic toll road with mountains on one side and green fields on the other. We sped by poplars, willows, fruit orchards, and olive trees. In the fields white bags full of cotton waited to be transported to factories. Fields of cabbage and corn gave way to pottery shops and houses with red tiled roofs near Selçuk. As we came to Kuşadası, our final stop of the day, the road rounded a turn and wound down the cliffs, with a splendid view of the Aegean.

Kuşadası (Bird Island) is a seaside resort town and a base for excursions to the ancient cities nearby. Many cruise ships on Greek island tours stop here, affecting both the town’s appearance and its markets for trinkets. The town is named after a small island, now connected to the mainland by a causeway. We were fortunate to stay in a hotel right on the water and away from the markets. Owned by the granddaughter of the last Sultan, Vahdettin, the building was a gift from her landowner husband, whom she met in the US during the family’s exile from Turkey. All dairy products and honey served at the hotel come from the family farm.

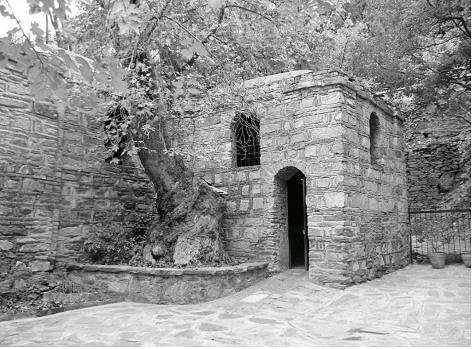

Virgin Mary’s house

Our excursion of the area began with the house of Virgin Mary, a shrine accepted in the 1960s by the Pope as a place for pilgrimage. It is believed that Mary Virgin Mary’s house came with Saint John the Apostle, lived, and died here. The house is located within a memorial park on a rolling hill. A footpath lined with olive trees, whose trunks are painted white to keep bugs away, leads to the stone house, which has a prayer altar and a fountain with holy water. On sale are white strips of cloth for tying onto wall-length screen fences to express a wish. The strips maintain uniformity of color and size, contributing to the contemplative setting.

As we walked downhill, workers cut and stacked wood on scorched hills — the result of forest fires set by Kurdish insurgents. The previous summer they had started seventeen forest fires near tourist areas, in order to harm the country’s economy. To extinguish the fires, helicopters had sprayed the pine forests with water brought from the sea. Workers’ tents crowded the hillside as part of a massive reforestation effort.

We continued to Ephesus, an ancient city first settled in 3000 BC. A trading and religious city, it was the center of the cult of Cybele, an Anatolian fertility goddess. Fleeing an invasion by the Dorians in 1000 BC, Ionian colonists came and replaced Cybele with Artemis, building a temple in her honor. When the Romans took over and made this the province of Asia, Artemis became Diana, and Ephesus was the provincial Roman capital in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. This is the city we visit today.

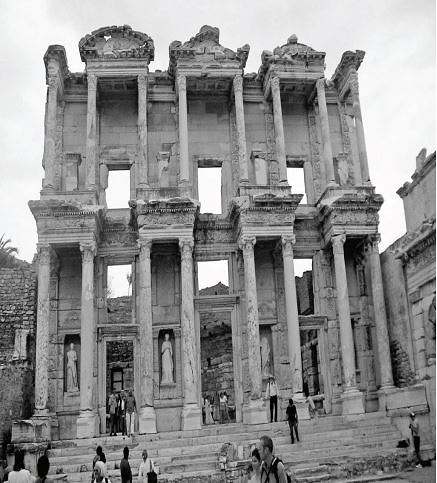

Library at Ephesus

Once a busy Roman port town with a population of 250,000, Ephesus is impressive with its ruins. The marble street where Saint Paul walked and the theater where he faced a rioting mob attract the most attention. The theater, which seats 24,000, and the agora are the largest the Romans ever built. There is a magnificent two-story library supported by marble columns and adorned with recessed statues. Other noteworthy buildings are the temple to Hadrian, the baths, the public toilets, the city council chambers, and the gymnasium. I marveled most at the terrace houses currently under restoration. These are homes with caryatid columns surrounding a courtyard, or peristyle. The walls are decorated with marble panels and fresco portraiture. The floors are carpeted with mosaics — chunky pieces on the edges and fine pieces for the medallion. The highlight of the Ephesus Museum was the statue of Diana, the fertility goddess.

The village of Şirince, 11 kilometers uphill from Ephesus, was our afternoon treat. Formerly a predominantly Greek village, Şirince lies in a valley, surrounded by peach orchards, vineyards, and olive groves. The village has retained its authentic 19th-century look of small white houses with red tiled roofs stacked against the hill. We called ahead for made-to-order lunch in a home restaurant called Gözlem. Stuffed squash flowers and mantı (Turkish ravioli with garlic yogurt) were among the specialties we enjoyed. At my request the restaurant even purchased fresh figs. Recent tourism has brought souvenir shops to this village of 600. All the shop owners know one another, and direct one to the right place depending on what one is looking for. Following a tip by American friends who had previously visited Şirince, I was able to locate a shop that specialized in jewelry combining semiprecious stones with needlepoint motifs — truly unique.

Heading north to ancient Pergamum, we passed by İzmir, Turkey’s third largest city, with a population of 3 million, and a major export harbor. Likewise a city steeped in history, İzmir (ancient Smyrna) has unfortunately turned into a busy, cluttered metropolis with a labyrinth of industrial plants and shanty towns. I was saddened to see that hit-or-miss expediency in the growth of many Turkish cities had claimed this one too, suffocating its dignity of old. We also passed by Aliağa, a town wealthy because of its refineries. Turkey imports and refines fuel oil. Following coastal roads and passing through resort towns, we arrived in Bergama.

Bergama (ancient Pergamum) sits on a high, steep hill in a rolling pastoral countryside of green fields. After the death of Alexander the Great and the breakup of his empire, Lysimachus claimed the region and established the capital of the Attalid Dynasty here in 131 BC. Pergamum became second only to Athens, brimming with culture, its hilltop crowned with palaces and temples, and its hillsides terraced with elaborate public buildings — an enormous theater, a library, schools, gymnasiums, baths, and a great altar to Zeus, the statues from which are now in Berlin’s Pergamum Museum. (The Germans conducted digs here before World War II.) The Attalids were also patrons of the arts. They invented parchment — untanned skin of sheep or goats — as an alternative to papyrus, which they had to buy from their rivals, the Egyptians.

Asclepium at Pergamum

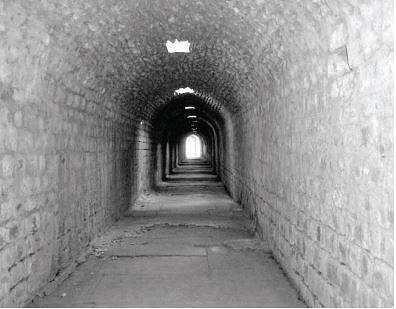

The Asclepium, a medical center for ailments of the mind or body, had a sacred spring, restoring baths, cubicles for sacred sleep, and a small theater for the convalescent. Patients walked through the colonnaded gallery to receive a diagnosis and prescription from the gods, who interpreted dreams. They left votives upon healing. (Asclepius was the Greek god of healing.) We noted the relief of a caduce — a wand with two serpents entwined, which is the symbol of medicine. The serpent represents longevity because it renews itself by shedding its skin.

Like nimble goats we walked up and down trails through rubble, admiring the panoramic view. Then we descended to the town center, to a restaurant called Sağlam, where we enjoyed local specialties, such as höşleme, made by mixing the cheese culture of the day with semolina. The owner of the restaurant sang for us: “Fawn, stray not in these mountains; for you’ll be shot and parted from your parents.” This sad song turned out to be a metaphor for the singer himself, who was from Urfa in southeastern Turkey.