October 2006

My friend Connie, born in Istanbul to missionary parents, invited me to join a tour of Turkey she was organizing in the States. The itinerary she designed was based on her fond memories of traveling through Anatolia with her parents. I welcomed her invitation, as the itinerary included cities that I had either not seen or not visited since 1964, the year my late husband Paul had been a Fulbright research fellow in Turkey. The trip, escorted by our superb guide, Evin Egeli, exceeded all expectations.

Already in Istanbul for a week, I joined the group of fifteen upon their arrival at the Arcadia Hotel on Sultanahmet, an old square named after the eponymous mosque, which is famous for its blue-tiled interior and six minarets. Quickly settling in my room on the sixth floor with a distant view of the Marmara Sea beyond the minarets of the Blue Mosque, I decided to stroll while the others rested from their overseas journey.

It was the first day of Ramadan; festivities and aromas permeated the air. The narrow cobblestone streets were packed with shoppers getting ready for iftar, the dinner that ends the day-long fast. The smell of special Ramadan pitas sprinkled with black cumin seeds wafted out of bakeries. Women and men in traditional garb, the former in long coats and headscarves, the latter in skull caps, mingled with jean-clad Turkish youth and wide-eyed tourists. The müezzin’s call to prayer, amplified to the street, pierced through the din of the square, reminding people of their mid-afternoon obligation. As masses hurried to the Sultanahmet Mosque, I stood aside watching this spectacle of humanity, since this part of Istanbul is very different from the modern area I am accustomed to, where such traditions are a rare sight.

I then walked over to the Çifte Hamam (Double Bath), constructed by the great architect Sinan in 1556 and known for its innovations in Turkish bath architecture. Currently the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, to promote the art of handmade Anatolian carpets, uses this building for exhibitions and sale. One of my favorite places to visit, this unique setting displays the depth and breadth of carpets and kilims (flat-weave rugs) with motifs from various regions of Anadolu, or Anatolia, which means “land of the East” in Greek.

Our welcome dinner was in the Arcadia Hotel roof restaurant, with a splendid nighttime view of the old city. The six minarets of the Sultanahmet Mosque lit up at dusk to signal the end of fasting. Lights delineated the balconies of the minarets along with the domes and half-domes of the mosques. Pigeons, home for the night, carpeted the rooftops across the way; modern Istanbul shimmered in the distance.

We enjoyed platters of cold and warm meze (appetizers), such as feta cheese, stuffed peppers and grape leaves, tiny meatballs, and fried phyllo dough triangles, followed by the main course, hünkâr beğendi (which means “the Sultan’s favorite”). This is a classic Ottoman dish of small cubes of mutton served over pureed eggplant. A seasonal salad accompanied the meal, which ended with crème caramel and Turkish coffee. We had been forewarned by Connie to leave our diets at home. We enjoyed delicious food with local variations throughout the trip.

A trip to the Spice Bazaar the next morning was a feast for the senses. We walked through narrow alleys lined with small stalls of multicolored spice cones, olives, dates, coffee beans, and candy. Alternating strings of dried okra, peppers, eggplant, corn, and garlic, along with goat cheese in its original skin, decorated the storefronts. Stacks of natural sponges, brooms, glass beads, copperware, and brassware added to the visual feast. The adjacent flower market featured seeds, bulbs, potted plants, birds, and rabbits. Here one could also buy tripe and sheep’s trotter, which are generally served at special eateries.

Walking through the Long Market, a street of shops for household gadgets, we reached the Rüstem Pasha Mosque, a small jewel built by Sinan in 1561. This mosque, built for a pasha, has only one minaret, as opposed to those with multiple minarets for sultans. Wearing headscarves and leaving our shoes at the door, we walked in. A wall-to-wall carpet, divided by designs into rectangular units, indicated the prayer space per person. Renowned Iznik quartz tiles adorned the walls.

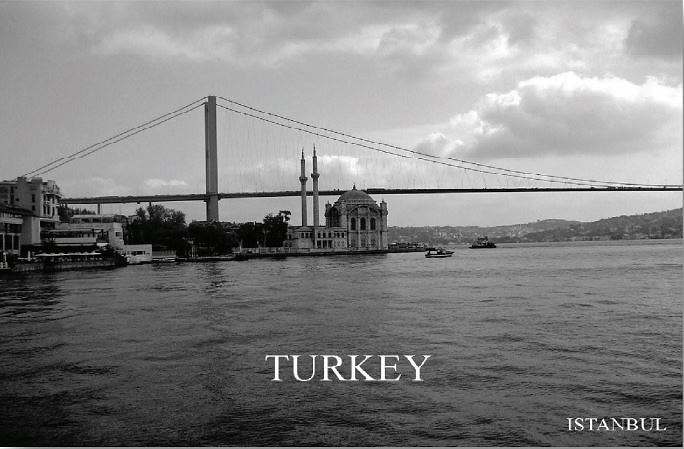

An excursion on the Bosporus by motorboat allowed us to view both European and Asian shores, as Istanbul straddles the two continents. We passed by old palaces, luxury hotels, some wooden houses in decay, and others restored as seaside villas with gardens. Cruise liners, passenger ferries, cargo ships, leisure craft, and fishing boats dotted the seascape, which opens to the Black Sea. Two suspension bridges between the continents added to the beauty of the setting. We disembarked at the widest point of the Bosporus in Tarabya and continued by bus to Sarıyer for lunch at a seafood restaurant called Aquarius.

Lunch was a feast from the sea. Cold meze of stuffed mussels, octopus, pickled sea bass, and mackerel preceded warm meze of squid, fried mussels, and fish wrapped in phyllo dough, leading up to the day’s catch of grilled bluefish, the main course. Turkish meals end with fruit, which in this case was black grapes and melon.

Nearby we visited the Sadberk Hanım Museum, which houses the private collection of the family of Vehbi Koç, one of Turkey’s great industrialists. The museum consists of two restored 19th-century waterfront mansions. One is dedicated to the archeology of ancient Anatolian civilizations from the 6th century BC to the end of the Byzantine Empire, the other to the ethnology of the Ottomans, including textiles, costumes, and handicrafts. A reconstruction of a fancy room where mother and newborn baby would be confined for 40 days so as not to catch germs by going out made me think of the circumstances following my own birth.

Our long day culminated at a restaurant called Sarnıç, which is the Turkish name for the Roman Underground Cistern. Near the Haghia Sophia Museum, the restaurant is in a 1600-year-old Roman building with massive stone columns and a brick ceiling, which has been restored for fine dining. The menu is a fusion of Turkish and French cuisine, featuring crepes and bon filet with Roquefort dressing. The highlight was ice cream hand-churned in the style of the southeastern city of Maraş and flavored with salep, an extract of dried orchid tubers — delicious. As we walked back to the hotel, Ramadan festivities around the square were at their peak. Popular tunes streamed from loud speakers, vendors strolled around with zithers and tambourines, and people milled arm in arm sampling food from various stalls.

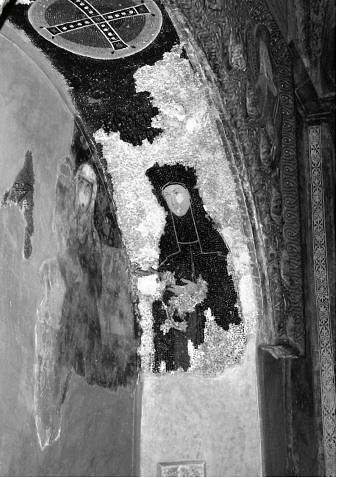

Mosaic in Kariye Museum

To beat the crowds, we started out early for Haghia Sophia (the name means “Divine Wisdom” in Greek), a huge church built in 337 AD by Emperor Justinian. Its dome, 32 meters in diameter, rises 56 meters above the floor and is surrounded by galleries and semi-domes. The walls are covered by mosaic tesserae glazed with gold and then fired. The church, used by Christians for 1000 years, was converted into a mosque for another 500 after the taking of Constantinople in 1453. In 1932, during the early years of the Turkish Republic, the Christian imagery, which had been whitewashed by Muslims, was cleaned and the building restored as a museum.

The Kariye Museum is another former Byzantine Orthodox Church with impressive mosaics. These are in good condition, as the Ottomans disguised the Christian imagery behind wooden fences here instead of whitewashing it.

The Süleymaniye complex is a 16th-century masterpiece by the architect Sinan. In addition to a grand mosque, the complex has royal tombs, a medrese (religious school), a library, a fountain, and a soup kitchen, where we enjoyed traditional Ottoman dishes and sweets for lunch. Afterwards we strolled through the alleys of the Grand Bazaar. I spent most of my time in the Sahaflar, the second-hand book dealers’ section of the bazaar near Istanbul University, where I purchased three works of ebru — a painting and printing technique of marbling oil paint and water into free-form designs and swirling decorative patterns with a comb.

Our third day in Istanbul consisted of visits to the Blue Mosque, Topkapı Palace, and the Underground Cistern built to store water brought from the hills above the Bosporus via aqueducts. Medusa’s heads, turned on their side by newly initiated Christians who did not appreciate pagan symbols, support two of many columns in the cistern. Goldfish inhabit the dark waters; coins tossed in for good luck glisten in the murky bottom.

Topkapı Palace is a complex of buildings for Ottoman royalty. We visited fifteen of the 100 rooms in the Harem, which was serviced by black eunuchs castrated in Africa and sold. Since free labor is sinful in Islam, the eunuchs were all paid. Murat IV built the Baghdad Pavilion in honor of the conquest of that city. Here silk-cushioned low divans facing the Sultan’s seat surround a large carpeted room with inlaid woodwork and a brass brazier in the center. The walls are covered with Iznik tiles.

The glass cases in the treasury display jewelry and other objects studded with diamonds, rubies, and pearls, plus a dagger adorned with the world’s largest emerald. Embroidered caftans, children’s clothing, bedspreads, and kitchen utensils were among other royal possessions we saw. At noon the Mehter, the palace band, played in the courtyard. Near the palace the old Mint, or Darphane, is now a bookstore run by a historical society where unique books on Turkey in both English and Turkish are sold.