January 2011

In 2011 Boston experienced several major snowstorms before my planned seven-week journey to South Asia, starting in Sri Lanka. As I feared, a pending snowstorm on January 12 caused British Airways to cancel my flight to London, where I was to connect to a flight to Delhi, and from there continue to Colombo. In order not to miss my London connection, I had to fly out of Boston a day earlier than planned and with only three hours’ notice!

Arriving in London early allowed me to catch up on my sleep by checking into a day room at Heathrow Airport, as my Delhi flight was now eight hours away instead of two. Feeling refreshed and relieved of my winter jacket, scarf, and gloves, I boarded British Airways again for the eight-hour Delhi leg of my trip. The 60º F in Delhi felt good compared to the 20º back home. Taking off my socks, I felt ready for the even warmer climate ahead in Colombo, now only another 3½ hours away.

India Jet Airways welcomed us with a serving of chicken curry followed by rice pudding, all served with proper silverware. As the flat landscape of Colombo on the Indian Ocean appeared below, I was reminded of the 2004 tsunami which had devastated much of Sri Lanka’s coastline. Once I was on the ground, the laid back friendliness I saw while waiting for my luggage to be delivered reminded me of visits to the Caribbean islands. Instructed by phone by our local guide, I took a cab to our group’s hotel in Negombo, a fishing town six miles north of Colombo where we spent the first two nights.

Negombo fisherman

Visiting Negombo allowed our group of fifteen an easy transition before the commercial bustle and pollution of Colombo, the capital city. Amid groves of coconut palms silhouetted by smog, we walked to the seashore, passing women in long skirts with baskets of cleaned fish on their head. Fishermen go out to sea at 2 am in order to have their catch cleaned and ready for the morning market. Sri Lanka is the richest fishing area in the world, as there is no land mass around to claim the fish.

Fishing craft such as outrigger canoes and catamarans brought fish large and small, ranging from swordfish, tuna, and barracuda to herring, mullet, and sardines. Little sprats sparkled in nets as they tried to escape; drying fish blanketed the reddish sand; blackbirds hovered above as dogs sniffed about on the ground. The Negombo Fish Market displayed a variety of shellfish — lobster, prawns, and very large crabs — in addition to assorted fresh and dry fish.

Although Sri Lanka is predominantly Buddhist, Catholic churches dot the landscape of Negombo, as Portuguese were the first colonial settlers, occupying the island’s coastal areas in 1505. The Dutch captured the town twice from the Portuguese, before losing it to the British in 1796. Negombo was an important source of cinnamon for the Dutch, who built canals to carry spices on barges. Ornate churches and other buildings are still reminders of colonial days.

Of the 21 million population of Sri Lanka, 3 million live in greater Colombo. We drove through dense traffic of buses, cars, motorcycles, and tuk-tuks to reach the city proper, home to one million people. Low income houses congregate along the canals; most buildings — new and old — have a veneer of mildew due to all the surrounding water and dampness. The cosmopolitan city revealed itself as we drove by churches, mosques, Hindu temples, Buddhas, and stupas. Nuns in white habits, women in saris, men in Muslim caps, and women in chadors accentuated the streets, which were full of colonial and modern architectural contrasts.

Our city tour began in the Fort district in the center of colonial Colombo. The original fort was built by the Portuguese, expanded by the Dutch, and dismantled by the British, who instead built streets with neoclassical buildings during their rule in the 19th century. The district retains its colonial character, with crumbling buildings lining a grid of streets. Much of the area’s charm has vanished, however, due to the civil war, under repeated bombings from the Tamil Tiger guerillas. Large sections of this area are cordoned off for security reasons, as it is also the neighborhood of the President’s house; therefore, no photography is allowed.

The current president, Mahinda Rajapakse, enjoys popularity for defeating the Tamil Tigers and reclaiming all rebel-held territory in 2009. Since the failure of negotiations for total surrender, 80,000 members of the Tamil Tiger network have been put in camps in the northern part of the country, to which even organizations such as Amnesty International have no access. 18% of the population are Hindu Tamil, who feel discriminated against by the Buddhist Sinhalese.

At the heart of the Fort district is its landmark, the Lighthouse Clock Tower. This hybrid structure no longer serves as a beacon for ships, as new high-rise buildings block its view from the sea. Also by the harbor is Saint Anthony’s Cathedral, which is visited by people from various faiths eager to tap into the saint’s miraculous powers.

Following a lunch break of seafood pasta at the Liberty Plaza shopping mall, we drove to Cinnamon Gardens, an exclusive suburb of Colombo named for the plantations of cinnamon which grew here during Dutch times. The area has wide streets shaded by canopies of tropical trees and lined with old villas. On Independence Avenue is Independence Commemoration Hall, a national monument built as a memorial to independence from British rule and establishment of the Dominion of Ceylon in 1948. The monument was built on the site of the formal ceremony marking the start of self-rule with the opening of the first parliament. Located at the head of the monument is a statue of the first prime minister of Sri Lanka, Don Stephen Senanayake, known as the “Father of the Nation.”

Colombo functions on a one-way street plan to minimize traffic. Negotiating our way through gridlocked streets, we were able to fit a few more sites into the day’s itinerary before returning to Negombo. Viharamahadevi Park is an expansive open green in the city; originally known as Victoria Park, the green was renamed after independence, taking the name of a Sri Lankan, rather than a British, queen. The park features a large Buddha statue, along with ebony, mahogany, lemon, fig, and eucalyptus trees among lotus ponds. Here resident fruit bats hang on trees during the day, waking up at dusk. Overlooking the park is the Town Hall, built in 1927 — a neoclassical building topped with a white dome and Sri Lankan flags. The national flag bears a lion with a sword in the center, and has two vertical colored bands on the left representing minorities — green for Muslims and orange for Tamils. A large golden Buddha sits in front of the Town Hall.

Moonstone

The Gangaramaya Temple is a modern Buddhist structure, with a “moonstone” at the entrance. A moonstone is a semicircular slab of polished granite, serving as a spiritual doorstep from the physical world to that of Nirvana. While details of carvings vary from temple to temple, moonstones share common features. They have an outermost ring showing flames, which symbolize desire. Within the flames are allegorical representations of four animals — an elephant (birth), a horse (old age), a lion (sickness), and a bull (death). Inside the circle of animals are vines, representing attachment to life; next, proceeding inwards, are geese, which stand for purification. Having crossed these bands, one arrives at the center, where there is a carved lotus representing attainment of Nirvana.

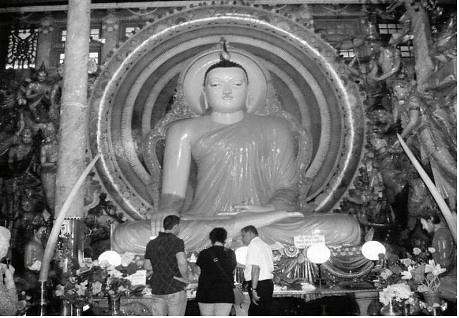

Beyond the temple entrance is the main shrine, filled by a giant fluorescent orange Buddha and a host of attending deities and disciples. A courtyard leads to various shrines to other gods revered by Sri Lankan Buddhists. The temple also has a museum with a vast collection of items given by devotees over the years, including sandalwood and ivory carvings, brass gods, crystal and jade statues, and elephant tusks.

Buddha of Gangaramaya Temple

The following morning we left for the central part of Sri Lanka, heading north toward Dambulla. Traveling through villages, we passed houses with thatched roofs of coconut palm leaves and others with clay roofs to keep interiors cool. Buddhist flags along with the president’s photo seemed to be everywhere. Colorful ribbons of political parties were occasionally replaced by white ones, heralding a death in the village. We drove onto a rough country road with puddles, but with picturesque emerald rice and pineapple fields. Laundry dried stretched on shrubs; stray dogs searched for food; people on foot or on bikes carried heavy loads. Signs in Sinhalese stood out with their curved round characters, as opposed to the angular ones used in Tamil writing.

Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage

Turning off at Kurunegala, we drove onto a paved road, alternating with secondary roads, to reach the Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage, which provides sanctuary for elephants orphaned or injured in the wild. Founded in 1978 with six baby elephants, the orphanage now cares for 65, including one that stepped on a landmine during civil war clashes. The orphanage also has its own breeding station, which has so far reared twenty elephants in a natural habitat.

The elephants were bathing in the shallow waters of the Ma Oya River when we arrived. Watching some 65 elephants splashing around in the river together was a unique spectacle. We were also able to see them return from the river for feeding. Their daily routine includes three feedings a day, followed by bathing.

Visiting the Elephant Dung Factory was another unique experience. Here we watched the process of making paper by hand using elephant dung, yielding a textured product with earth-tone filaments. While I did not buy any paper, I felt lucky to find an eight-inch replica of a granite moonstone in one of the many souvenir shops.

Including the visit to the Elephant Orphanage, it took us a full day to reach Dambulla, which is in a plain in the dry zone — defined as including any place with less than 39 inches of annual rainfall. Trees here have smaller leaves than in the lush coastal regions. The area is rich in vegetable crops, as well as ancient architecture and art. Wholesale markets are busy throughout the night, loading up trucks to supply big cities. Following a delicious meal, the highlight of which was delicately spiced mashed pumpkin, we settled into the Thilanka Resort and Spas for the next two nights.

Early the next day we headed south to Sigiriya, a natural rock formation. This is a UNESCO World Heritage site dating back to the 3rd century BC, when Buddhist monks lived in the caves at its base. We drove by rice paddies, which were flooded by communal lakes created by dammed rivers. Storks looking for insects dotted the fields, which were surrounded by earthen dams to conserve water. Nearby treehouses served as nighttime lookout stations for farmers to chase away elephants, which like to eat new rice crops. They are scared away with firecrackers, known locally as “elephant crackers.” An occasional peacock roamed about, while large squirrels nested on trees.

As we approached Sigiriya, it began raining. Donning raingear and umbrellas, we first visited the Archeological Museum, a state-of-the-art new building constructed with financial aid from Japan. The museum holds artifacts found during excavations, such as terra cotta objects and farming tools, as well as replicas of cave frescoes.

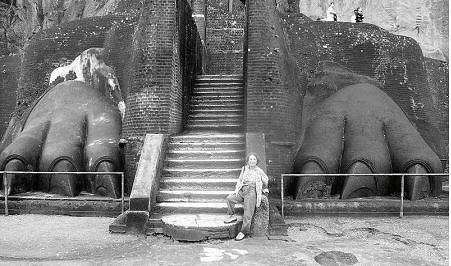

Sigiriya Lion Platform

Through a thick mist we began our ascent of the enormous rock, 200 meters above the surrounding plain. Following a narrow metal staircase of over 1000 steps, we first reached the Lion Platform and from there the spacious Summit with views all around. Here stood the former Royal Palace of King Kassapa, who reigned between 477 and 495 AD. Upon hearing that his half-brother was the designated crown-prince, Kassapa killed his father, King Dhatusena of Anuradhapura, establishing a new city at Sigiriya (“Lion Rock”), both to claim his kingship over the “lion race” and to be at a defensive location surrounded by sheer rock faces.

The royal palace had pavilions set amid gardens and pools. The rock was transformed into an immense lion by the addition of a head and forelegs, of which only the sculpted paws remain. In addition to the Lion Platform and the Summit ruins, the complex includes the Water Gardens, the Boulder and Terrace Gardens, the Mirror Wall, and the Apsara Paintings, Sigiriya’s most celebrated sight. Commissioned by Kassapa in the 5th century, a painted band of apsaras, or celestial nymphs, on the sheer rock face depicts sensuous women scattering flower petals or offering trays of fruit.* These naturalistic paintings are the earliest surviving examples of Sri Lankan classical realism. Despite the rain, the exhilarating ascent and descent to and from Sigiriya, coupled with the sight of these frescoes, was already well worth the trip to Sri Lanka.

* See postcard image at beginning of article.

Lunch was at a fast food restaurant, where we saw locals eating with their hands. In general Sri Lankans do not use silverware, instead using their right hands to scrape food off their plates. The left hand is considered unclean and does not touch food. A new taste was yogurt with honey derived from a plant rather than made by bees. At a government-run craft store, I bought a small wooden elephant painted decoratively with a floral pattern. Walking around the wholesale market, we learned about betel nuts, which many locals enjoy chewing like tobacco. The nutmeat is sold rolled in betel leaves, which serve as a pouch for the remainder while part of it is chewed.

On our second day in Dambulla we climbed 300 steps to reach a pair of temples — the Golden Temple and the Rock Temple. The Golden Temple is a modern creation full of kitschy embellishments, with the exception of its 100-foot-tall Golden Buddha, which sits behind the temple in the asisa mudra position, that is, raising his right hand in a gesture of blessing. This Buddha has a refined simplicity and serenity, as opposed to the temple’s gaudy facade. A row of statues of orange-clad monks bringing offerings to the Buddha, in addition to some fake elephants on the ground, enhance the astonishing view. Here I bought a small chunk of pink quartz unique to the area.

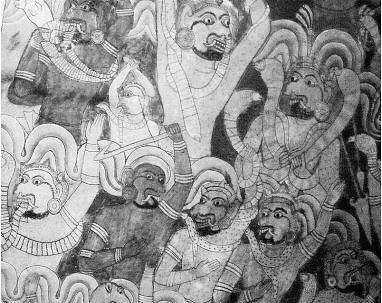

Fresco of attacking demons

in Dambulla cave

The Rock Temple nearby is awe-inspiring. Originally created in the 1st century BC, the imposing Dambulla Rock is divided into five cave temples of varying sizes. The first and third caves have colossal reclining Buddhas carved out from a single piece of rock, 46 and 30 feet long respectively. The second cave is the largest and most spectacularly decorated, with an array of Buddhas lined up around the sides. Impressive frescoes, painted in the 18th century, cover the walls and ceilings, depicting different aspects of the Buddha’s life. Using squirrel or monkey hair, two families painted the murals in exchange for land from King Kirti Sri Rajasinha.

The paved scenic route to Kandy, hill capital of the old kingdom and center of the country’s Sinhalese culture, offered various points of interest. The Spice Garden introduced us to typical spices of Sri Lanka — cardamom, coriander, cinnamon, and nutmeg, which thrive with high rainfall and humidity. Pepper dried in the sun becomes black peppercorn; boiling produces white pepper. Roast cocoa beans make dark chocolate, which is high in caffeine. Various spices and herbs are used in ayurvedic medicine for natural ailments; cinnamon oil, for instance, is used for earaches and dry mouth.

At a batik factory we watched craftsmen drip hot wax with a special tool, following free-hand designs on cotton or silk cloth. Dipping the material in the dye bath determines the preliminary color of the design, before the wax melts away by pressing or boiling for application of a second color. The art of batik was introduced to Sri Lanka by the Dutch, who brought it from Indonesia.

Although Kandy is the country’s second largest city, it has a small town feel. Streets lined with low-rise colonial buildings give the center a special charm. The scenic centerpiece of the city is Lake Kandy, bounded by elegant white buildings against a rich green backdrop. The winding hills are lined with villas of the wealthy, which enjoy views of the Knuckles Mountain Range.

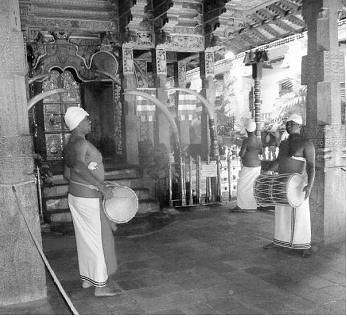

Drummers at the

Temple of the Tooth

Perched at the eastern end of the lake are the white buildings of the Temple of the Tooth, the most sacred temple in Sri Lanka. The main shrine is home to one of the most sacred objects in Buddhism, the Tooth Relic, which is kept in a Golden Casket in a room upstairs. The doors to this room are opened only during thrice daily worship rituals, to the accompaniment of traditional drumming. We joined the throngs of pilgrims and locals, mostly dressed in white and carrying flower offerings in bamboo baskets, to file by the Golden Casket. However, it was impossible for us to approach the casket because of the density of people. The only photo I managed to take had three heads blocking most of the view.

A visit with a monk informed us further about Buddhism in Sri Lanka, where the religion is preserved in its original Theravada tradition. Observers of this tradition believe that one is personally responsible for one’s own spiritual welfare, and that the only route to Nirvana is through constant spiritual striving, unlike the Mahayana tradition, which believes Nirvana can be achieved through devotion and prayer to various deities. Buddhism is taught as a subject in schools; the most respected people in the country are the monks. Parental permission is required to become a novice at age ten, with full ordination occurring at twenty, meaning commitment and dedication to spreading Theravada Buddhism, which nowadays includes using modern technology.

Full Moon Day, an official holiday, is the holiest day of each month, as the Buddha urged his disciples to perform spiritual acts on every full moon. The devout spend this day at the temple; no alcohol is sold or served. To fulfill the Buddha’s wishes for equality, no hats or shoes are allowed in temples, where the preferred attire is white or light tones soothing to the eye. Fortuitously, our time in Kandy coincided with Full Moon Day. An impromptu visit allowed us to observe a “homecoming ceremony,” an auspicious event where a bride’s family receives the groom after a wedding.

A performance of traditional Kandy and lowland dances demonstrated the influence religion and folk traditions play in the daily lives of Sri Lankans. The Pooja Dance paid homage to deities; the Mask Dance drove away evil spirits. The Fire Dance showed man’s power over fire, while a Fire Walk performed by a dancer in a trance sought the blessings of the Goddess Pathihini.

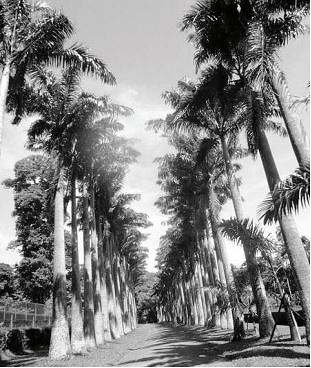

Royal Palm Alley

in Botanical Gardens

Four miles from Kandy in Peradeniya are the Royal Botanical Gardens, which occupy a horseshoe-shaped peninsula, around which flows the Mahaweli River. The 147-acre lush gardens, with 4000 species, are a treasure trove of trees and plants from tropical regions of the world. At the entrance is Royal Palm Alley. The Great Lawn is home to a giant Javan fig tree, which covers 17,222 square feet. Other highlights are the Orchid House and Gardens, the Flowering Trees, and the Arboretum.

Kandy is also a city of gems, found in the ancient rocks of the hilly countryside. We visited a gem factory, where we watched a simulated mining operation. Once inside the pit, miners break down the surface using crowbars, following which other workers wash the pieces in baskets to spot the gems. Jewels are sold to the highest bidder in auctions, where hand gestures made under a piece of cloth take the place of verbal communication. Sri Lanka is a major source of rubies and sapphires in the world.

Hill Country

For the final leg of our trip we traveled to the highlands south of Kandy, known as Hill Country. Our destination was the town of Nuwara Eliya, known for beautiful landscapes and tea plantations at an altitude of 6500 feet; to reach it we climbed slowly on roads with hairpin turns winding through dramatic mountains. Waterfalls cascaded through verdant hills, glistening with tea bushes. In the 19th century it was the inspiring scenery that attracted the British to this place; they cleared the mountain wilderness to cultivate coffee, then introduced tea upon losing the former crop to fungus devastation. A combination of abundant rainfall, sunshine, cold nights, and mist offers the perfect climate for producing the aromatic teas now known worldwide as Ceylon tea.

Halfway between Kandy and Nuwara Eliya our road skirted the magnificent Ramboda Falls, which tumble over cliffs in 300-foot cascades. Shortly before reaching Nuwara Eliya, we stopped at the Mackwoods Labookellie Tea Factory and Estate for a tour. We walked among neatly manicured tea bushes, planted amidst lemongrass to prevent soil erosion. Bushes are pruned every few years to keep their size manageable for picking. Tea is picked during the cooler part of the day, between 6 am and 1 pm. Only the topmost bud and two leaves are plucked, in order to guarantee freshness and purity; then in the factory the leaves are withered by blasts of hot air. Rolling releases the remaining sap and triggers fermentation, following which the leaves are dried in ovens to produce black tea and sifted for grading by size.

Based on the size of leaf fragments, finished teas are given names such as “broken orange pekoe,” “orange pekoe,” etc. “Dust,” a low quality tea, is used in tea bags. Sri Lankan teas are also ranked according to their altitude of origin. “High-grown” teas, cultivated above 3000 feet as in Nuwara Eliya, are the finest; “mid-grown” or “low-grown” teas, produced in the foothills, are full-flavored and coarser. Experts classify the teas according to strength, flavor, and color. After this educational tour, we enjoyed freshly brewed tea in porcelain cups in the garden of the estate; then we had a chance to visit the gift shop, which was doing a brisk business. As I was only in the first week of a seven-week journey, I refrained from stocking up on tea, but did purchase a mug, the proceeds of which benefited a school for hearing-impaired children.

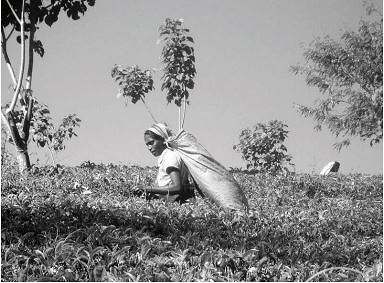

Brightly dressed Tamil tea pickers, amongst glossy green bushes with breathtaking distant views of valleys and mountains, form one of Sri Lanka’s indelible images. Initially recruited by the British as seasonal workers, Tamil plantation workers stayed on when tea cultivation required year-round labor; thus they settled in the hills, changing the ethnic composition of the region. To this day their descendants have poor living standards and remain among the lowest-paid in the country. Each laborer stakes out an area and is able to pick twelve-to-fourteen pounds of leaves a day; tea is picked twice a week in the wet and once a week in the dry season. The daily wage depends on the weight of a wicker basket taken to the factory when full, and is usually around $7. Only recently have Tamils working on plantations been recognized as citizens. Because the reality behind the picture-postcard image is grim, photography comes at a price.

The town of Nuwara Eliya, which has a distinctive British flavor, is known as “Little England.” Built in the 19th century, its architecture mimics that of an English country town, with brick walls, country clubs, and mock Tudor half-timbering. Sri Lanka’s wealthy, who are in the shipping business or deal in gems, enjoy this area, with its mild climate and breathtaking views, as a holiday retreat; their bungalows, along with guesthouses and hotels, dot the hills. English-style agriculture, introduced here more than 150 years ago, is still going strong; beets, cabbages, leeks, potatoes, and strawberries thrive in the mild climate, replenishing wholesale produce markets daily.

The Colonial Grand Hotel, where we stayed overnight, gave us a taste of British country life. This massive old structure, with its landscaped lawns and topiary, has a huge ballroom, an Edwardian tiled dining room, and a Victorian lounge. Wedding preparations were underway in the ballroom, with a photo shoot of the bride. The photographer would not allow me to take pictures, so I was unable to document the beautiful bride in her lavish gown. Astrology plays a big role in the lives of Sri Lankans. Astrologists are consulted to determine the most auspicious times for marriage, starting a new business, or breaking ground for a new home.

Tamil tea picker

In the morning we headed back toward Colombo, south of Nuwara Eliya, driving by hills terraced for growing vegetables and more tea plantations. From a distance dark Tamils picking tea leaves in their colorful saris looked like giant birds among the plants. As I rushed to photograph them, I made sure I had rupees to distribute. As we drove on, we heard what we thought were dogs barking; but our guide, Sumedna, said they were leopards living in the dense rainforest further away. More plantation laborers appeared on the hills; this time they were men fertilizing and pruning the tea plants. Pilgrims passed us on their way to Adams Peak, where a footprint at the summit is ascribed to the Buddha. There are 8300 steps in the climb, which takes four hours.

In the town of Hatton, we happened upon a Skanda Hindu ceremony. Skanda is the god of war, worshipped in Sri Lanka and southern India, where each temple is dedicated to a particular god. Once a year Skanda is taken out of his temple, put in a chariot, and pulled by devotees through the streets for all Hindus to see, as lower caste people may not go into the inner temple chamber, where Skanda resides. We watched men prepare the chariot in the midst of a big crowd, burning a lot of incense; the rising thick smoke made photography difficult. I was unable to get a glimpse of the god.

Descending to the rainforest area, we passed by a rubber plantation. Rubber is tapped twice a day; it is a major export item for Sri Lanka, providing 3% of gross national income. We stopped for lunch at the Plantation Hotel in the valley of the Kelari River, where people come for bird watching and white water rafting. Young locals here act as guides. This is a beautiful setting for family outings as well. Seasonal tropical fruit — banana, papaya, pineapple, pomelo, and star fruit — was in abundance.

Finally we descended the mountain and came onto a flat paved road for the last three hours of our trip. Our driver stopped periodically by roadside shrines to ensure us a safe journey. We arrived in Colombo during rush hour, which is between 4:30 and 6:30 pm. It was mayhem entering the city. Passing by children trying to keep cool in white school uniforms, and many shops selling motorcycle parts, we inched our way through fanfares of bus horns and choking fumes to the Hotel Galadari, at the southern end of the Fort district on Galle Road across from the Parliament. As this was a high-security area, we were advised to take photos only facing the Indian Ocean. Although our hotel faced the water, the cacophony of vehicles kept me from crossing Galle Road to take pictures or to explore this strip of modern-day Colombo.

Fortuitously it was seafood night at our hotel. At our farewell dinner we were treated to a buffet of seafood — shrimp, prawns, squid, and fish — prepared in a variety of ways. My parting purchase from the hotel shop was a packet of toothpicks made from the carved stem of a coconut leaf. The next morning our flight to Chennai, India required an arrival time of three hours before departure. When we arrived at the airport, we found that our flight was delayed by 2½ hours. I spent some of this unexpectedly long wait browsing the airport shops. I could not resist purchasing a silk jacket hand-crafted in Sri Lanka. With five more weeks ahead of me, I hoped that there would be no further delayed flights to tempt me at airports as I traveled.