January 22, 2011

The depth and intensity of my month-long India experience began in Chennai (Madras), the gateway to Southern India. Tucked in the northern corner of the state of Tamil Nadu by the Bay of Bengal, Chennai on the Coromandel Coast, with a population of 6 million, is India’s fourth largest city and the state capital. Tamil Nadu is on the same latitude as Guatemala. The best time to visit is in January and February, before the hot weather sets in.

Driving in from the airport, we saw streets teeming with beautiful women dressed in saris of striking colors; they walked on dirty sidewalks and crossed chaotic streets full of everything minus the legendary cows. Ravi, our guide, explained that cows had been outlawed from the state’s major cities because of their contribution to traffic accidents. The hotel staff welcomed us with thick rope of marigold garlands, then, in keeping with Hindu tradition, placed a vermillion tilak (mark) on a spot centered between our eyebrows to open up our third eye, the eye of wisdom.

Beauty, deep-rooted spirituality, and kaleidoscopic culture are constants in Indian life. The varied cultures go back to around 3500 BC, when the Dravidians, the aboriginal people of India, settled in the Indus Valley, now in Pakistan. In the 3rd century BC Buddhist Aryans arrived from Central Asia, bringing their gods with them, and settled along the Ganga (or Ganges) River. Aryans eventually mixed with Dravidians, contributing to the birth of Hinduism and its pantheon of gods. Tamil Nadu, with a population of 17 million, is the center of Dravidian culture.

A morning stroll took us through a market by makeshift stands under parasols; women with garlands knotted into their lush, oiled braids bloomed like colorful flowers amid evident poverty. As we walked by heaps of coconuts, pineapples, cabbages, cauliflower, and carrots, banners above reminded people in English to wear helmets while riding motorcycles or to harvest rain water. In nearby Georgetown, Victorian elegance defined the town’s eclectic architecture. Attracted to cheap local cotton, British merchants came to Madras in 1639 and quickly established a textile trade, contributing to the city’s growth and prosperity, the British name Madras was changed to Chennai in 1996 to reflect local pride. The British built Fort Saint George, which now serves as administrative headquarters for the state legislative assembly. The fort also houses Saint Mary’s Church, the oldest Anglican Church in India, built in 1680.

San Thome Basilica

On our way to the San Thome Basilica in Mylapore at the southern end of Marina Beach, we saw fishermen’s dwellings dotting the landscape. Makeshift tents held up by poles alternated with laundry drying on lines tied to sticks. Nets in plastic sacks sat in heaps nearby others stretched to dry. People cooked in pits in the sand. In the December 2004 tsunami, the seven-kilometer-long beachfront was washed out; the water came over the road, taking with it people playing cricket or jogging. The sea has strong currents and is not safe for swimming. I learned here that the word “catamaran” is a Tamil word meaning “tied wood.”

San Thome is the Portuguese name for Saint Thomas, an apostle of Christ who came to Madras in 52 and died as a martyr in 72 AD. He was buried in Mylapore; the gothic cathedral, built in 1606 over his tomb, was made a basilica in 1956. A stained glass window behind the main altar portrays the story of Saint Thomas, whose remains are now in Ortona on the Italian Adriatic coast; some earth taken from his tomb is in a silver casket inside the basilica. A three-foot-high statue of the Virgin Mary was brought from Portugal in 1543. Believers maintain that, when the 2004 tsunami struck, the area behind the Basilica was protected by the Pole of Saint Thomas, erected by the saint to protect people living near the shore.

Our next destination, Mahabalipuram, 60 kilometers south of Chennai, is a 7th-century port city of the Pallava dynasty and one of 28 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in India. Traveling overland along the coast, we passed by wedding halls decorated at the entrance with bunches of bananas, symbolizing fertility, then drove onto a highway to reach Mahabalipuram, known for its Dravidian art and architecture. The GRT Temple Bay hotel was our base while we explored surrounding ancient sites. The hotel consisted of cottages surrounding a free-form pool, set within lush gardens near the shore — a beautiful spot.

Breakfast introduced us to specialties of southern India, in addition to Western-style food. The buffet included paja, goat’s feet cooked with curry leaves and served over dumplings, which are made by mixing rice flour and black lentils and steamed in molds after fermentation. The dish is eaten with chutney or dhal (lentils). Dosa is a thin crepe made with fermented rice flour and lentils, cooked on a hot iron, and eaten with a variety of chutneys — tomato, mint, and coconut. Indians, who are largely vegetarian, obtain their protein from dairy products and lentils, which are served at all meals. Freshly made paneer, or cottage cheese from buffalo milk, appears in many dishes; lassi — made with yogurt, water, and either sweet or salty flavorings — is a common drink to beat the heat.

Women planting rice

Religion of any kind is big in India. To accommodate overflowing crowds for a church service on Sunday morning, people were seated outside. An excursion to Kanchipuram, capital of the Pallava Dynasty from the 4th to the 9th century AD, took 2½ hours, even though it is only 43 miles away, because of traffic on narrow roads and numerous stops. We visited simple roadside shrines inspired by early primitive temples, which consisted of termite mounds and were protected by cobra statutes, both considered fertility symbols, or linga, because of their shape. On the road were buses known as “rolling hotels,” where passengers slept and drivers cooked for them. We passed by rice paddies; men in bare feet plowed fields with oxen, which had horns painted in different colors and which were decorated to show their owners’ gratitude following the harvest, while women stooped to plant rice, which thrives in the stagnating waters of Eastern India’s flatlands.

Kanchipuram is one of Seven Sacred Cities dedicated to both Shiva and Vishnu. Enriched by many rulers, the city is a center of Tamil learning, with over 50 functioning temples, where rituals of dressing gods gave birth to one of India’s major silk weaving centers. Our visit began at Kanchi Kudil, a traditional home depicting domestic history. Here was yet another example of the countless ways in which ritual underscores the holiness of daily life. Rice flour designs called kolam, which were created by female members of a household each morning, beautified the area outside the doorstep. These geometric patterns, sometimes in colored powdered stone, are believed to attract the gods, bring prosperity, and thwart evil spirits. Houses are kept clean to prolong the gods’ stay.

Along with pilgrims streaming to Kanchipuram (the City of Gold), cows lined the streets. All cows have owners, who like to let them wander, especially in sacred places. We visited two of the city’s most celebrated temples — Ekambareshwar and Kailasanath. The former, dedicated to Shiva, is the city’s largest temple. Built in 1509, the structure has a soaring gateway, which leads toward an equally huge hall, a colonnaded corridor, and immense pyramid-shaped towers covered with celestial gods. This temple is the focus of daily life; the gods are cleaned at daybreak, dressed, fed, and put to sleep at the end of the day. Devout men mark their forehead to denote the deity they worship. A Shiva worshiper has two or three horizontal lines, an adherent of Vishnu — vertical lines; an additional red dot indicates the belief that one’s deity is the Supreme Being. The marks are white, red, yellow, or black.

Dwarfs lifting

Kailasanath Temple

A lane near the temple is dedicated to selling puja, or worship items, such as garlands of roses and marigold blossoms, lengths of intricately knotted jasmine buds, and baskets of fruit or other food served on banana leaves, considered blessed if bought on the temple grounds. The ancient rock-cut Kailasanath Temple is dedicated to Shiva, indicated by a bull on the wall, as opposed to a lion, indicating the temple of a goddess. Built in the 8th century, the Kailasanath Temple has two-story halls, heavy horizontal lintels, and a worship space lifted by sculpted dwarfs and intricate carvings of Shiva, such as one showing the god stomping on the devil, and of dancing figures.

A lunch treat was pumpkin halvah with ice cream from buffalo milk — the secret of consistently tasty Indian ice cream. Silk shops line the streets of Kanchipuram. We visited one where weavers used a card loom. It takes up to three weeks to set up the design on such a loom. Threads are dipped in liquid silver or gold to weave brocade fabrics. Hand-woven silk saris sell for more than $1000.

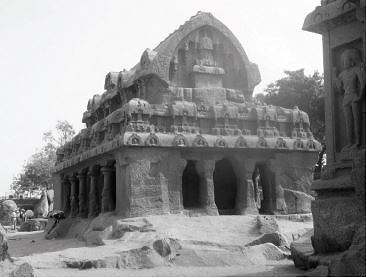

Returning to Mahabalipuram (the City of Great Fighters), we resumed sightseeing at our home base, situated on a rocky outcrop overlooking the bay and casuarinas trees. These are used for scaffolding, because of their straight branches, and for makeup, as their wood bleeds when cut. The city is an open air museum dotted with temples, sculptures, intricate carvings, and reliefs. The 8th-century Shore Temple was the first built temple after the use of rock-cut caves; it represents the early phase of Dravidian temple architecture — one principal gopura (gateway) leading into a courtyard and so to the porch, mandapa (hall), and main shrine. The temple has twin spires and three shrines, one dedicated to Vishnu and two to Shiva. It also houses the world’s largest bas-relief. Temples were built on high places to elevate the gods above men.

Monolith Temple

Among the common sights were women laborers, who stood out in their gaily colored saris, exotic bangles, and gold jewelry, sweeping temples or doing construction work for very low wages in dust and heat. Beautiful women with shaved heads, having sacrificed their hair to gods, underscored the Indians’ freedom from ordinary rationality.

The Monolith Temple is carved out of one piece of rock and depicts the Mahabharata epic. Temple carvings became more elaborate as religion evolved, including many more gods with kings and queens represented next to them.

Traveling 62 miles south to Puducherry (Pondicherry), we followed a scenic highway with the sea to the left and coconut trees to the right, interspersed with mango and jackfruit trees and bougainvilleas. Billboards advertising movies vied for attention; carts pulled by Brahma bulls with decorative red and blue stripes on their horns, and women washing clothes in puddles by the roadside enhanced the local color. We reached a lagoon filled with salt fields; women carried sand to strengthen dykes retaining water, and carried salt in baskets to create mounds when the water evaporated. The mounds were covered with palm leaves to protect the salt from moisture until it was loaded onto trucks for the wholesale market.

A lunch stop introduced us to southern Indian thaly, a vegetarian platter of ten small dishes served with a mound of rice on a banana leaf. Dishes ranged from spicy to sweet and included yogurt to temper the spices. On the side we enjoyed papad — crunchy lentil wafers seasoned with black pepper, garlic, and other herbs and spices.

Puducherry was a small village in Tamil Nadu until French traders arrived in 1623. Although the French lost the village to the Dutch and English several times, they restored its prestige and in 1756 began laying out the port town that still survives. Capital of all French settlements until 1954, Puducherry is now one of India’s union territories, with 14,000 French nationals among its residents. A large Muslim population, visible in burkas, lives in the southern part of the city, as wealthy Muslim merchants settled by the river early on.

Puducherry is divided into two quarters — the French Quarter (known as the Ville Blanche, or White Town) and the Indian Quarter (known as the Ville Noire or Black Town). A rickshaw ride took us through the French Quarter to the waterfront. Overlooking the broad vistas of the Bay of Bengal stands a statue of Mahatma Gandhi at the entrance to the pier. South of here is a statue of Joan of Arc and the Eglise de Notre Dame des Anges, built in 1855. Here French history — with its whitewashed colonial buildings, ornate ironwork balconies, and Catholic cathedrals — blended with local culture along the seaside promenade, creating a starkly different panorama from any other Indian city we had seen so far. This was despite the familiar sight of beautiful women and school girls with flowers in their hair on litter-strewn streets — a sight which continued through the alleys of the market as we walked by bolts of fabric, pots and pans, chili peppers, and a variety of fruit and vegetables.

North of the pier is the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, a yoga school and meditation center, which was founded by a foreign-educated Bengali known as “the Father” and his wife and disciple, a Parisian known as “the Mother.” It is common for individuals to be given near-godly status as they become popular by doing miracles. We walked in silence and bare feet through the Ashram, visiting the main building, the samadhi (tomb) of Sri Aurobindo and “the Mother,” and the publications room; no photography was allowed.

Ayyanar deity

After a breakfast of dosa made to order and selections from the buffet, we left for Tanjore, stopping on the way at a local village where rope is made by beating and drying the outer fiber of coconut shells. Used for mattress filling, rope, door mats, carpets, and runners, in addition to its oil for cooking, juice for drinking, and sap for sugar, the coconut is considered a fruit from heaven. A group of ayyanars — large, brightly colored terra cotta images of deities — in front of a small temple protected the village. The devout believe that equestrian deities, sometimes with horses and elephants, chase away evil spirits, protecting the village from calamity; therefore, a priest performs a special puja, and locals sacrifice chickens or goats, bringing the meat to the gods.

Traveling southwest on a two-lane paved road, we passed by Muslim homes, painted turquoise with crescent and star emblems above the doors. Honking as we approached curves, we dodged bicycles, motorcycles, and other buses. The landscape changed from sugar cane fields burnt after harvest to a variety of lentils planted between rice crops; we were entering the granary of southern India. At a mill trucks loaded up with sacks of rice, and women carried goods on their heads. On approaching the sacred Kaveri River, which flows into Bay of Bengal, tamarind trees lined the road, contributing to the peaceful setting of the delta.

After lunch in Kumbakonam, a popular pilgrimage site, we continued to Tanjore, passing through streets of visible poverty. There are 52 births a minute in India; the ratio of urban to rural population is 40-60, with poverty prevailing everywhere. Astrology is an important part of peoples’ lives. An appropriate match between the impression of one’s right palm and a figure in an astrology book determines one’s future. Temples are the center of peoples’ lives, providing shelter for many.

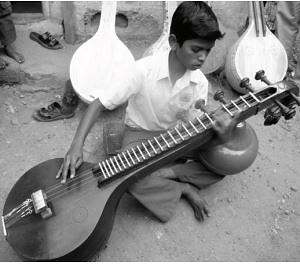

Playing the veena

Tanjore was the capital of the Chola Empire, the empire of the richest Tamil rulers from the 9th to the 12th century. Today a medium-sized, moderately paced city, Tanjore is known for its cottage industries, such as making musical instruments and bronze statues, and for bharata natyam, a classical temple dance. Our exploration of the city began with a visit to the homes and workshops of crafters of veena, a long-necked round instrument made from one whole jackfruit tree. We watched men carve out the sound box, adding intricate surface detail, while young boys demonstrated how the instrument is played.

Later in the day, we attended a dance festival on an outdoor city stage. As we waited for the performance to begin, we were entertained by barefoot neighborhood gypsy children moving to music from loudspeakers. The first half of the festival consisted of folk dances, some depicting horse and rider and others portraying peacocks, as well as acrobatics. The second half featured classical dances telling a story about Krishna with hand and facial gestures.

Wedding ritual

On the way to the Brihadisvara Temple the following day, we stopped to see a Hindu wedding ceremony. The ritual, performed on a raised platform, involved the bride’s parents accepting the groom into their family by putting a flower garland around his neck; in turn, the groom tied around the bride’s neck a piece of thread, symbolic of their bond. Guests were elegantly dressed — women in colorful silk saris with flower ornaments in their hair, men in all white traditional costume. Women sat at the front of the hall; men at the back; equally well adorned children sat with their parents — boys with their fathers and girls with their mothers. Most marriages are still arranged through what amounts to a contract between two families. The arrangements are sealed with negotiations over the dowry. The wedding is paid for by the bride’s family.

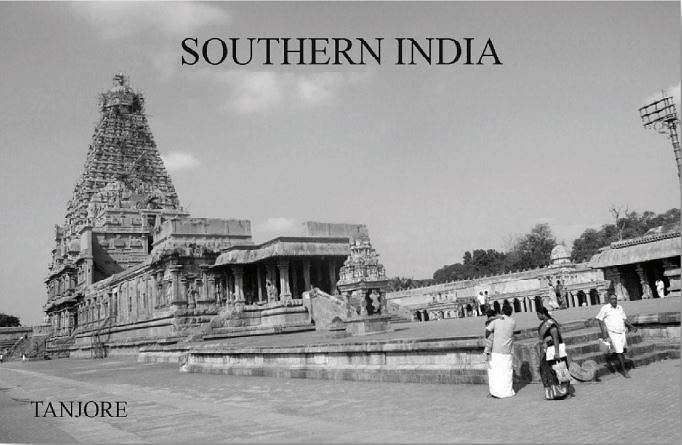

Life in Tanjore centers on the monumental royal Brihadisvara Temple,* built under Chola rulers, who claim descent from the Sun. Constructed in around 1010, the temple’s 217‑foot-high tower supports a gilded pot finial at the top. Destroyed by Muslims, the temple was rebuilt in the 16th century. Locals come here six times a day for puja, or prayer, beginning at dawn with a priest unlocking the door, and returning after work until sundown. Individuals receive prayers from the priest, who must be married, in return for money or other offerings. Pilgrims with shaven heads arrive, ringing bells to alert others to stay away lest they contaminate the food offering. Near the temple are sanctified spaces, such as a bend in the road or a crotch in a tree where hopes, represented by small objects and pieces of cloth, are tied to branches.

* See postcard image at beginning of article.

A walk through a visibly impoverished village introduced us to the craft of bronze work. We watched a dancing Shiva in the making, using the lost wax technique: first a figure is modeled from wax and placed in a clay mold, then an alloy of hot metals — bronze, gold, silver, and copper — is poured in to replace the wax model, which melts. After a cooling period, the clay mold is broken to reveal the metal object, which is filed and polished to a finished patina. I happily bought a small dancing Shiva.

Children at

the orphanage

Our visit to a local orphanage coincided with India’s Republic Day on January 26; the children were not in school because of the holiday. 200 happy and well dressed children, ages five to sixteen, welcomed us, and some danced for us in groups. The orphanage collected children reported not to have parents from six districts. We met the social worker, who had entered the orphanage at the age of two and was happy to be working there, having completed her studies; she was engaged to be married soon. We were also greeted by some of the 50 destitute older people who lived at the orphanage. All in their 70s with walking sticks in hand, these people enjoyed having their pictures taken and marveled at our ability to travel long distances.

The following morning we departed for Madurai en route to the west coast, making numerous stops along the way. Just as we neared the first stop, a phone call from our previous hotel alerted us that two people had left money and passports in the room safe. Realizing I was one of the two forgetful people, I panicked, even though I knew that a driver was on the way and would meet us halfway so that we would not have to drive back. Somewhat relieved, I was still nervous, not knowing whether my money and credit cards would arrive intact; but they did.

Women winnowing millet

As we traveled inland away from the river, dense traffic gave way to sparsely populated roads. We stopped to watch women winnowing millet, a substitute grain in regions where rice does not grow. By the roadside, cashew stands spewed smoke as women roasted nuts over fires fueled by shells. This semi-arid region is the ancestral homeland of clans of Chettinads, Tamil speakers from an ancient trading and money lending caste. Chettinads built opulent mansions side by side in tight village grids. The central town is Karaikudi, where we stopped for lunch in one such mansion, now a hotel run by a Chettinad widow. Lunch was served on long banana leaf plates.

One of the distinctive features of Tamil Nadu is its Chettinad cuisine, which uses every seed, legume, and fruit that grows in the countryside. Roasted spices flavor meats, such as goat, chicken, fish, and prawns cooked in freshly ground masala, made by mixing cumin, coriander, and fenugreek. Our lunch consisted of fish, chicken curry with mango chutney, beets with yogurt, spinach, and rice. For dessert we had fried dough in syrup with ice cream on the side. After lunch we walked around the town, which is situated in an unspoiled rustic landscape, and visited one mansion, which stood out with its intricately carved panels and immense chandeliers.

Continuing on our way, an educational stop at a batik workshop revealed the workings of this ancient craft. A design is drawn on paper, then transferred to a cloth by sprinkling powder through little holes in the drawing. Hot wax is applied using human hair wrapped around a bicycle spoke between different color baths — yellow, red, green, and black. Washing in hot water melts the wax away, producing beautiful multicolor designs on the cloth, which is hung to dry. It was admirable to see such beauty created by human ingenuity despite the surrounding poverty.

Wall carving,

Minakshi Sundareshvara Temple

Our next destination, the temple city of Madurai, the third largest city in Tamil Nadu and the oldest one continually inhabited in the country, surpassed expectations. The city, which dates back to the Sangam period of the pre-Christian era, served as capital for the Pandyas, who ruled southern Tamil Nadu from the 7th to the 13th century. The layout, symbolizing the structure of the cosmos, is inspired by the shape of the lotus flower, with concentric rectangular streets surrounding the Minakshi Sundareshvara Temple. Changing royal rulers several times, the city and temple prospered under the patronage of the Nayakas through the 17th and 18th centuries. Remodeled and redecorated continually since, the colorful temple complex is dedicated to Shiva’s consort, Parvati (known as Minakshi, the fish-eye goddess), and represents the final stage of southern India’s Dravidian temple architecture.

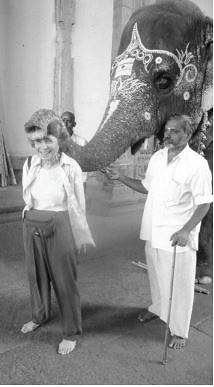

With resident elephant

Our visit fell on a Friday, an auspicious day for Hindus. Devout Tamils flocked to the temple by the thousands. Approaching the main gopura with its tapering tower, we were dazzled by its riotous decorations of gaily painted dancing and cavorting gods and goddesses. We wandered through the corridors and halls, admiring ceiling paintings and murals, and noting other tall, elegant gopuras. Sculpted dancing men and ferocious animals flanking corridors, as well as beautiful, sensuous groups of Shiva and Parvati figures, were rare finds. A hall with a seated figure of Nandi, Shiva’s bull, along with small Nandi shrines throughout, flickered with candles lit by worshipers. Sanctioned areas for adorned elephants and cows with painted horns enhanced the spectacle, as people lined up for puja to enter the inner sanctuaries.

In the evening we returned to the temple by auto rickshaw, to witness a night ceremony in which deities were put to sleep. Two women created an elaborate multicolored kolam, a ritual pattern using rice flour, on the floor to welcome the deity. Riding in a silver palanquin with drawn curtains and carried on the bare shoulders of four men to musical accompaniment, the deity passed by throngs of worshipers before his palanquin was finally rested on the kolam. Following a ritual which included flowers in a silver bowl and fanning with feathers, the palanquin was taken to sleeping quarters behind closed doors until dawn.

Between the daytime and nighttime temple rituals, we visited the Trimalai Naicker Mahal, a palace complex constructed in the Indo-Saracen style in 1636. Considered a national monument, the palace is divided into two parts, each with royal residences, shrines, apartments, theater, pond, and garden. A portico known as Swarga Vilasam is an arcaded octagon with 248 pillars, each 58 feet tall and 5 feet in diameter; intricate stucco work adorns its domes and arches.

In leaving Tamil Nadu, a relatively well-off state with good roads, fine schools, and a burgeoning technology industry, I felt fortunate to have seen the many of the folk ways and customs that have been preserved, along with the slow life revolving around worship and food outside the major cities. Soaring temple towers, mystical configurations, holy utterances, men in white dhotis (wide pieces of fabric worn around the waist in a tight skirt-like shape), and women with jasmine garlands in their hair were among my indelible memories as we headed west to the state of Kerala.

Embarking on a scenic overland trip toward the mountains, we passed by small towns with billboards announcing wedding dates of couples, along with their photos — an increasingly popular custom. Leaving rice and sugar cane fields behind, we stopped at a brick factory run by a husband-and-wife team. Laborers made 1500 bricks a day using local red clay, stacking them in a kiln in batches of 40,000. The bricks baked as the heat rose to the thatched roof of the low-firing kiln. Thanks to cell phones, the laborers had direct access to points of sales, thus skipping the middlemen previously relied on. Bricks were also sold by the roadside.

Our lunch break was at an altitude of 700 meters in Theni, where we learned about purie — whole wheat bread which puffs up into a ball when deep-fried. We watched women bathing in the river, while others did laundry by pounding the wash against rocks. Egrets cooled off in water puddles.

As we reached higher elevations, banana plants, cabbage, and cauliflower fields appeared. Banana plants have multiple uses: the flowers flavor lentil dishes; the green stems are cooked as a vegetable; the leaves — red, yellow, and green — are used as plates; the fibers are strung with jasmine to make garlands; and juice extracted from the stem heals burns. In addition, bananas in bunches decorate wedding halls as symbols of fertility.

Climbing up and down the mountain, we crossed the border to Kerala. India has seven mountain ranges; the Nasik range separates the east and west coastal regions, which are very different from one another. Our destination, Periyar, a protected nature reserve, was in the middle of a mountainous area of the Cardamom Hills near the border with Tamil Nadu. The driver had to show papers, as is required at checkpoints between states. Teak trees and giant bamboo lined the state border in Kerala, which we entered in Kumily, a town with a very different look from the places we had just visited. A large Pietà sculpture commanded the town center, which was dotted with Christian Orthodox churches.

Crossing Lake Periyar

by bamboo boat

Muthoot Cardamom County, our home for two nights, was located within a small portion of the Periyar Wildlife Sanctuary, also called Thekkady, set aside for tourists. The sanctuary surrounded Lake Periyar, which was formed by damming the Periyar River. In the evening we enjoyed a dance performance on the terrace of the hotel. A solo classical dancer wearing ankle bracelets performed bharata natyam, opening herself up to the gods through hand and facial gestures.

In the morning we crossed the lake by bamboo boat to go on a nature walk through the forest. We saw monkeys, Asian bison, wild boar, barking deer, leopard foot prints, porcupine holes, termite mounds, and many birds, including cormorants. Spiders were at work between tree branches; touch-me-not flowers closed up when touched.

Curry leaves

Thekkady is the location of Kerala’s major spice plantations, where curry leaves, the secret to southern Indian cooking, are in abundance. We had a cooking demonstration, helping a husband-and-wife team make curried eggs. To prepare the gravy, one cooks chopped onions with mustard seeds before adding cardamom, curry leaves, turmeric, salt, and pepper. To this aromatic concoction are added coconut milk and eggs, which are sliced in half with thread to keep them from crumbling. We enjoyed the curry with a pancake made of fermented coconut milk and rice flour and cooked on a hot griddle, along with papad — slightly spicy, crunchy wafers of lentil flour seasoned with pepper, garlic, and other herbs and spices.

At an elephant camp nearby, we enjoyed a different perspective of the surroundings on elephant back. A wondrous walk through various sections of a spice plantation provided close-up views of native pepper plants, tamarind trees, cinnamon bark, ginger root, cardamom, clove, nutmeg, and turmeric. The abundance of plants on the cultivated slopes of the plantation made it clear why so many people from different lands were attracted to this tiny state for the spice trade as early as 1500 BC, contributing to the state’s ethnic makeup and diversity — 60% Hindu, 21% Christian, the rest Muslim of Arab origin.

Tamils were the first group to settle in Kerala; Aryans followed. Therefore, both Tamil and Hindi are spoken. However, the language of the mountain settlements is Mala Yala, a mixture of ancient Sanskrit and Tamil. Kerala, the size of Belgium, covers 1.03% of India’s total land mass; yet it is one of the most densely populated of the country’s 28 states. 3.5% of India’s population lives in Kerala, with an average of 800 people per square meter.

Dutch colonists arrived in Kerala in the 17th century and introduced the rubber plant from Indonesia, where they cultivated rubber. Acres of rubber plantations cover the green landscape of the state. The British arrived in the 18th century and introduced tea plantations, along with cabbage, carrots, beets, and potatoes, all known as “English vegetables.” The British popularized tiger hunting and joined maharajahs on hunts. They built hill stations to escape from the heat, and dotted the hills with prep schools for their children and children of the Indian elite. These schools continue to operate as boarding schools for the wealthy. The literacy rate in Kerala is around 95%.

Heading 45 miles west to the port city of Cochi (Cochin), we traveled with views of the mountain range, huts with roofs made of elephant grass, and flowering trees, including African tulips, which are common in southern India. We passed through small mountain villages, tea plantations alternating with silver oak trees, and brightly painted houses in the valley at a distance. We stopped by the roadside for toddy, a local palm wine fermented fresh each day — tart, pale white, invigorating, inexpensive, and a great way to become somewhat tipsy. Our next stop was at a tree nursery, which was bursting with flowers, even on the roof of the main building. We walked through cardamom woods, where the plant grows at the feet of tree trunks; smelled peppermint plants, lemon grass, and ginger; and admired holy cross orchids.

Syrian Orthodox church

At 3300 feet, the Franciscan Brothers Pilgrim Shrine, an ornate Syrian Orthodox church, commanded the highest point on our road. Following a brief photo stop, we continued to a rubber plantation for a tour and lunch with the owners in Mundakayam, a small town in Kerala. We were welcomed with a refreshing pineapple and coconut drink, followed by an educational tour of a small segment of the plantation, which has 450 rubber trees planted 150 per acre. The rubber plant produces a sticky white sap, which is collected and processed to produce natural rubber, sold as latex. India is the world’s fourth largest rubber producer.

Cups are tied to trees cut for extracting sap, which is collected between 6 and 10 every morning. Processing the sap involves heating it, passing it through a press into sheets, and drying it. After a few days, a rubber tapper makes another cut above or below the first one to extract more sap from the tree. In about 20 years a rubber tree stops producing sap, upon which a new tree is planted in its place.

Our hosts, a Christian family, waited on us during lunch, which consisted of chicken curry, rice, vegetables, yogurt, and pineapple from the plantation. Afterwards we viewed the wedding album of their recently married daughter, who had had a lavish Indian wedding with 2000 guests.

Known as the “Queen of the Arabian Sea,” Kochi, which means “the Port,” is Kerala’s second largest city, with a population of 2 million. It is a coastal settlement that spreads across islands linked by ferries and bridges. As we entered the city, colonial buildings and historic churches provided a glimpse of its Portuguese, Dutch, and British heritage, whereas its skyline of high-rises reflected recent Arab investment. Red flags with hammer and sickle emblems fluttered everywhere, down to small refreshment stands. Kerala has a democratically elected communist government and was the first to have one, along with Kolkata, where ideals of socialism and communism are also quite important. Party members — Hindu, Christian, and Muslim — observe religious traditions.

Driving through congested and littered streets, we arrived at the Killians Boutique Hotel behind a guarded gate. Across the street was a lovely house with a high garden wall, which cautioned people not to write on it, although goats scampered about the trash-filled sidewalk for scraps, while buses, tuk-tuks, and motorcycles negotiated their way around them and each other. Here was yet another contrasting example of wondrous India, where trash and beauty coexisted. It seems inherent in the culture to discard rubbish on the streets, while keeping homes and stores clean. Municipal services simply cannot keep up with the trash generated on sidewalks and in empty lots.

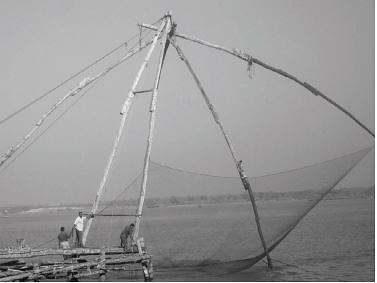

Cheena vala fishing net

In the morning we walked to the waterfront, passing by giant rain trees planted by the Portuguese, and arrived at a spectacle of elegant cheena vala (Chinese fishing nets) at the docks. Unique to Cochi outside of China, these nets dot the photogenic coastline. Fishermen earn their livelihood daily by using a pulley system to lower wide empty nets attached to teak frames and pull up full ones. Afterwards we walked over to the Saint Francis Church, the oldest European church in India, built in 1503. This was the initial burial place of Vasco da Gama, whose body was later exhumed. Tombstones of Dutch people buried on the grounds have been brought inside and line the walls of the church; hanging cloth panels on either side of the sanctuary work as fans to create a breeze. The church’s history is representative of colonial struggle in the subcontinent.

Mattancherry Palace, built by the Portuguese for the Rajah of Cochin in 1555, is also known as the “Dutch Palace” because of its renovated tile roof and whitewashed walls. The palace is a quadrangular structure built in traditional Kerala style, with a courtyard in the middle. The dining hall has an ornately carved and varnished teak ceiling. The flooring, which looks like polished black marble, is a mixture of burned coconut shells, charcoal, lime, plant juices, and egg whites. The palanquins that carried the rajahs are in the throne room. The gallery has portraits of the Cochin rajahs in chronological order, the last one being the rajah who lived in Cochin after independence; his statue still stands in the city square. Colorful murals of the palace are recognized as some of the best examples of Hindu temple art, depicting the time of matriarchal lineage, when women dressed only from the waist down, until the arrival of the British, who imposed full clothing. No photography is allowed in the palace.

Entrance to

Pardesi Synagogue

Kochi has a rich Jewish history; Sephardim Orthodox Jews, who came from Majorca, built the Pardesi Synagogue in 1568 and settled in nearby Jew Town. The winding alleys of this area are lined with shops filled with spices, antiques, and curios. As we walked to the synagogue, the air was thick with the scent of cardamom and cloves. The synagogue has Belgian chandeliers and colored lamps, and giant scrolls of the Torah. The floor is covered with hand-painted blue Cantonese tiles, originally ordered for the palace. Upon hearing that the tiles were painted using cow hair, the rajah gave them to the Jewish temple in 1762. A rabbi lives in the temple; all but seven of the Jews have moved to Israel. Those who have stayed come for service on Fridays, when the synagogue is closed to visitors. We had to check our cameras before entering the synagogue. I bought a few postcards here, in addition to a beautiful white reverse appliqué cloth and a small painting on wood signed by the artist in the market.

A home-hosted dinner in the evening gave us a glimpse of local Hindu life. Our host family, with two daughters, ages 15 and 21, lived in a gated community in the new part of Cochi, located on an island outside the city. Since we had to cross a bridge during rush hour, it took us an hour and a half to get there, although it was faster on the way back. The hosts were a traditional family; the father did most of the talking. He was quick to tell us that he was the boss and intended to make decisions regarding the marriage of his daughters, as he believed in arranged marriages.

The women waited on us and said little, except the older daughter, who was a graduate of the local International School and now teaching preschool. The younger daughter, in jeans and T-shirt, was in the 9th grade at the same school, where students learned English, Hindi, and a local language of their choice. There are 80 official languages in India, five of which are Dravidian languages spoken in the south. English and Hindi are spoken in the national Parliament; local languages are used in state government.

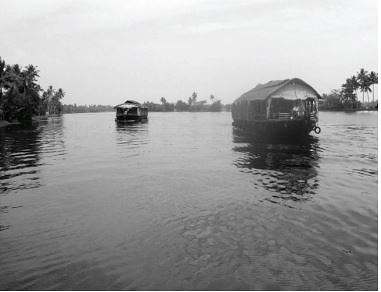

Kettuvellam houseboats

on Kochi backwaters

In the morning we explored the scenic backwaters of the Malabar Coast aboard a houseboat called a kettuvellam. A 60-mile-wide strip between the water and the mountains makes it easy to transport spices to natural ports, and so is also densely populated. 30 miles out from Cochi, a backwater region called Allepuzha (Aleppy in English) resembles the Louisiana Bayou. We cruised by river terns sitting on utility wires stretched across the river between wooden poles, tied up goats, and ducks fenced in the shade of village hamlets, where people carried on with their daily lives. Hyacinths crowded the water’s edge, while egrets enjoyed a high perch on coconut trees leaning toward the sun. A center for ayurvedic treatment — an ancient healing system based on rebalancing the body through herbal treatments and yoga exercises — sat back amid shrubs. Villagers bathed or washed in the shallow waters, which rise to a level of up to 50 feet during the monsoon season, flooding homes and forcing people to move to camps further inland.

A peaceful four-hour boat ride through palm-fringed canals included lunch — fried fish, chicken curry with rice, beets, beans, sliced cucumbers, tomatoes, and carrots. For dessert we enjoyed fresh pineapple and banana fritters dipped in a batter of flour, sesame seeds, and turmeric — delicious. We disembarked for a bus ride to the town of Aleppy, where we watched boats being repaired. At a coconut fiber shop my lucky find was a picture made with dried sheaths of rice, cut up to form an image in the natural yellow shades of the plant.

Kathakali character

The evening’s treat was a performance of kathakali, a stately Kerala dance, at the Cochi Cultural Center in the Fort district near our hotel. Literally meaning “story play,” kathakali, over 400 years old, is performed with painted faces and costumes of symbolic colors. Accompanied by a percussionist, characters from Indian epics perform the stylized dance drama, representing existence in three worlds — those of gods, demons, and humans. Elaborate make-up is used to portray the slow metamorphosis of mortals into immortal deities and demons; the process takes two-to-three hours to complete. Using natural pigments, the actors transform themselves into mythical beings and become larger than life by wearing elaborate headgear. We watched the Pacha character complete his make-up on stage to depict a scene from a full-length story that lasts from dusk through the night in temple courtyards.

We left the hotel at 6 in the morning to go to the airport, 50 miles from Cochi, to catch a 7:30 flight to Bengaluru (Bangalore). This capital city is located on the Deccan Plateau in the southeastern part of the state of Karnataka. Perusing the in-flight magazine during the 40-minute flight, I happily noted several Indian films dealing with women’s issues such as coming of age, challenging traditional chauvinist values, and arranged marriages, as women declared their financial and sexual independence. The magazine articles ranged from democracy since Gandhi and Nehru to Marxist ideals. I anticipated learning more about such topics while traveling among states, which differ vastly in cultural terms.

Bengaluru is the information technology capital of India, and as such the country’s third largest city, with a population of 5 million. High-tech multinational companies are attracted to the year-round mild climate, along with the highly educated young population of a state where the average age is 25, and have their headquarters here. The education system, set up by the British early in the colonial period, is heavily subsidized by the government, and the country’s leading institutes of management and technology are based in Bengaluru.

Since its first settlement in 1557, the city’s growth has been steady, reaching 78% in recent years. Much new construction, including a metro system, is underway; soaring glass skyscrapers of software companies and call centers, providing global technical support, dot the skyline. India aims to be a global technical superpower by 2020.

Leaving dense traffic behind, we traveled southwest to Mysore, known for its palaces and gardens, as well as its silk and woodwork industries. Enriched by the Kaveri River, the city is surrounded by lush rice paddies, as well as fertile sugar cane and vegetable fields. Mysore was the capital of the Wodeyar Dynasty, which ruled the state of Karnataka for 150 years until India’s independence from the British. The rajahs shaped the delightful character of the city, preserved today partly because Mysore does not have an airport.

Monolith of Nandi, Mysore

Our excursion began at Chamund Hill, a prominent landmark at the eastern outskirts of Mysore. At the crest of this 3000-foot-high mountain with a panoramic view of the city sits the Sri Chamunddeshwari Temple, which dates back to the 11th century and is dedicated to Mysore’s patron deity of the same name. Reached by road or 1000 steps, the temple has a striking pyramidal temple tower,* added in 1825. Halfway up the stone steps is the Monolith of Nandi, Lord Shiva’s mount bull, carved out of black granite in 1659. The bull, decked in garlands and bells, receives offerings from the devout throughout the day.

* See site logo in upper left corner.

One can never say one has seen enough temples in India, as each is architecturally wondrous depending on the kingdom and period in which it was built. Therefore, I signed up for an optional tour to see the Kesava Temple in Somnathpur. The 20-mile trip from Mysore took us 90 minutes of riding up and down country lanes through wide open spaces on the undulating Deccan Plateau. We passed buses with locals riding on the roof, fields full of birds, and betel nut trees. Meanwhile Ravi gave us some facts about the temple, which was built as a gift for a royal wedding in 1268 and took 58 years to complete during the reign of the Hoysala Kingdom, known for its unique temple architecture.

The small temple is a star-shaped gem standing on a raised platform, which symbolizes the universe, held up by elephants. There are three towers and three shrines, each with a different revelation of the god Vishnu. Friezes of elephants and epic scenes, intricately carved out of soapstone, which hardens afterwards, adorn the base of the outer walls. Small images tell Hindu myths, with intervening columns of gods and goddesses and their attendants. Unique to Hoysala are the lathe-turned pillars of the great hall and delicately carved ceilings with banana motifs symbolizing fertility. The temple is no longer used, as some of its statues are broken and thus not in the perfect condition required for worship. A majestic 300-year-old Bengali ficus tree with a small shrine sanctifying its base completed our visit of the temple grounds.

Returning to Mysore, we visited the Lalitha Mahal Palace, now a five-star hotel, where we enjoyed lunch. The shimmering white palace with a grand double staircase was built by the maharajas (the royal family) in the 1920s during British imperial rule. It served as a residence for the British head of state and for meat-eating European guests of the strictly vegetarian maharajas. Our lunch buffet, served in the elegant former ballroom, featured a variety of refreshing meat and vegetable salads flavored with fruit such as pineapple, orange, and banana. Following lunch and a tour of the former palace, I stopped in a few of the gift shops, where I purchased a hand-carved sandalwood peacock displaying its “feathers” and a miniature painting of a Hindu festival procession on elephant back.

Our afternoon visit to a silk shop was both educational and artful. Karnataka produces 65% of India’s raw silk. Japanese male moths are mated with Mysore females. Once hatched, the pupas are sold to farmers, who rear them to cocoon stage. The worms, placed on woven mats, continuously eat mulberry leaves for about a month, during which they molt and grow. They then turn from white to yellow and spin their cocoon for about four days. The cocoons are then sold for boiling, reeling, dying, and weaving. India has Asia’s biggest cocoon market. The shop had a variety of beautiful silk items at reasonable prices.

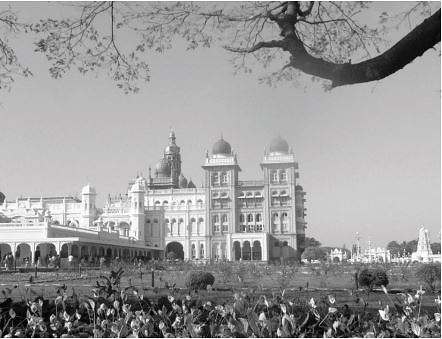

Amba Vilas Palace

Afterwards we visited the pink marble-domed Amba Vilas Palace, also known as the Maharaja’s Palace, designed by English architect Henry Irwin. A three-story structure in the Indo-Saracen style built from 1897-1912, the palace has square towers with covered domes at cardinal points. To go in we had to check our cameras and take off our shoes. The Durbar (Audience) Hall has rows of carved pillars, huge inlaid ivory and silver doors, and marble work with semiprecious stones. The octagonal Wedding Hall, with its glazed tile flooring, has long friezes recording the town’s Dussehra festival, celebrating the triumph of good over evil, domed stained glass ceilings with peacocks, and cast-iron pillars. The maharaja’s howdah (elephant riding seat), encrusted with 24-carat gold, as well as eight enormous bronze tigers are other notable treasures; a jewel-encrusted golden throne is displayed in the Durbar Hall during festivals. The walled palace complex has old temples and a museum; it is illuminated on Sundays and holidays.

Dye cones in

Mysore market

A walk through the market was our final activity for the day. Dyes in vibrant colors stood out in cone-shaped heaps in stalls; mounds of rose and jasmine garlands beckoned from carts or caught the eye coiled up in baskets. Narrow alleys lined with spice shops created an intoxicating air, while produce of every kind and bangles of every color enhanced the photogenic chaos. Sensations continued over a farewell dinner of dishes flavored with curry leaves and peppers, some sweetened with coconut; the meal was topped off with rice pudding sprinkled with cardamom.

Nine miles north of Mysore is the mausoleum of Tipu Sultan on the island fortress of Srirangapatnam on the River Kaveri, where we stopped on our way back to Bengaluru. The British stormed the citadel and killed Tipu Sultan, confirming their supremacy in southern India, which had been ruled by Muslims from 1766 to 1799. Gumbaz, a tomb and mosque complex built by Tipu Sultan as a tribute to his father, Hyder Ali, after his death in 1784, is at the eastern end of the island. Set in an Islamic cemetery garden with cypress trees, Gumbaz enshrines the cenotaphs of Hyder Ali, his wife Fahr-un-Nisa, and Tipu Sultan; the tombs are covered with jasmine garlands from visitors. The mausoleum is built on a stone plinth, with polished black granite pillars running along a corridor around the inner chamber. This chamber is painted in tiger stripes, associated with Tipu Sultan, who was called the “Tiger of Mysore.” A dome crowns the building. A mosque, the Masjid-e-Aksa, graces the peaceful grounds.

As we continued our overland trip to Bengaluru, Ravi talked about social change in India. Affirmative action laws give preference to those who have suffered under the Hindu caste system. Those who used to be marginalized are now the majority in the ruling party. Although negative attitudes toward lower caste people still linger, they are gradually losing their hold. Those below the poverty level receive a government subsidy of staples such as lentils and rice; health care and medicine are subsidized for all. Farmers receive free electricity.

Ravi also explained the name change from Bangalore to Bengaluru. The native language of Karnataka is Kannada, in which the name of the city is pronounced “Bengaluru.” Name change brings psychological change; the word “Bangalore” represents an outsider’s view, while the new name is the nation’s own. Ravi proudly pointed out that Indian languages are now taught in US universities. Talagu, Tamil, and Hindi are taught at graduate level; the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Iowa offer instruction in Kannada.

Our main two-week tour of southern India ended in Bengaluru, where those of us continuing on a post-trip to Goa and Mumbai had some leisure time until our departure the next morning. Unfortunately, we had to say goodbye not only to our travel companions returning home, but to our superb guide, Ravi, as well. India is such a big country that guides certified to work in the south cannot work in the north and vice versa. By now I was about halfway through my trip, although it seemed much longer because I had already seen, experienced, and learned so much. I decided to spend my half-day leisure time refueling and reorganizing my bags, as the weight I had picked up along the way was a source of concern for my flight the next day.

Despite the weight of my hand luggage, I could not resist picking up two items at the airport — a shirt and a kurta, a loose top that falls below the knees, usually worn over form-fitting pants. My distinctive kurta is green with a gold-sequined scoop neck and magenta trim. At the annual holiday dinner of the Women’s Travel Club we are encouraged to wear something we have picked up during our travels; here was my outfit. The other shirt is lightweight black cotton sprinkled with silver sequins on either side of small mother-of-pearl buttons halfway down the front. These were the first ever sequined purchases of my life.

Goa is a tiny state located along India’s southwest coast. Created as recently as 1987, it is characterized by a fusion of Hindu and Portuguese heritage. Our hotel, the Lemon Tree Goa, was located on Candolim Beach in northern Goa. Set back from the road in a garden with a pool, the interior decor accented Portuguese traditions in imagery, mosaics, and stained glass windows.

Covered market

Our tour started with a walk through the fish market, where women vendors, their saris tucked up, crouched beside baskets of shrimp and other catches of the morning. In the covered market, shoppers negotiated narrow aisles between beautifully arranged stalls with baskets full of fresh and dried produce, flowers, bread, tobacco leaves, and sacks full of garlic, red chilies, and dried tamarind, which gives a bitter richness to local dishes. Along the walls and on the second floor, small box-shaped shops stocked everything from wine to bangles. In addition, the second floor rewarded visitors with a bird’s-eye view of the lively ground floor.

Colonial homes in Panaji

Afterwards we drove to Mirabar Beach on the Arabian Sea and enjoyed a walk on its red sandy shores. Nearby in Panaji, the capital of Goa, we visited the hilltop parish church, Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, a dazzling whitewashed structure built in 1619 in Portuguese baroque style with twin towers. The town’s Latin Quarter was enchanting, with its Portuguese flair, down to street signs and well kept traditional colonial houses.

The walled city of Old Goa is an ancient port on the Mandovi River which became the capital of the Portuguese maritime empire in 1510. An international city for trade, it also became a center for Roman Catholicism with the arrival of Portuguese missionaries. The churches and convents of old Goa were declared UNESCO World Heritage sites in 1986. They display an impressive array of European baroque architecture with ebullient decoration, high altars, twisted columns, flying angels, and a great deal of gilding.

The Basilica of Bom Jesus (1594-1605) is a focal point for Goa’s substantial Catholic population. This Jesuit church holds the mortal remains of Saint Francis Xavier, called Goencha Saiba (Lord of Goa) in Konkani, the local language. A public viewing of the local saint’s body, believed to have miraculous healing powers, takes place every ten years (the last one was held in 2004). Other major churches are the Cathedral of Saint Catherine and the Convent and Church of Saint Francis of Assisi. The convent, which is annexed to the church, now houses an archeological museum, which has been functioning since 1964. The museum’s holdings include Hindu temple antiquities, stone replicas of early and medieval objects, as well as wooden and bronze sculptures from the Portuguese period.

After a morning of enjoying bygone splendor, we had lunch at a restaurant called the Coconut Tree. The luncheon menu reflected Goa’s heritage of various cultures and culinary traditions, enriched by a large expatriate population drawn to its sun and sandy beaches. Hawaiian chicken with pineapple, fried sea bass with tartar sauce, and custard for dessert were among the offerings.

Many Europeans have settled in Goa, bringing with them a cafe culture to satisfy their coffee nostalgia in the land of tea plantations; now tourists as well as locals pack the cafes, contributing to the vibrancy of the streets. Cashew shops are plentiful. We stopped by one specializing in roasted cashews flavored with cardamom instead of salt — delicious. We spent the rest of the afternoon at leisure. Walking around on my own, I enjoyed the carefree rhythm of the streets, although I missed the beautiful dark-skinned women with flower garlands knotted into their shiny hair. Hungry for the sun, northern Europe had descended on Goa.

The next morning we traveled south to Colva, driving by cashew orchards and fields of red and white lotus — the red kind closes at around 1 pm and white kind at around 5 pm. On the way we learned about two types of pineapples — reddish and yellow-green — and five kinds of bananas. Each village has a fish market and a produce market, and as of recently, a recycling center; the use of plastic wrapping has been banned. Colva has an 18th-century high baroque church, Our Lady of Mercy, in addition to lovely Portuguese homes.

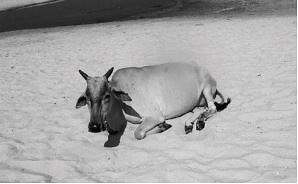

Cow on the beach

With a 27-kilometer-long white sandy shore, it also has Goa’s longest beach front, lively with water sports, cafes, restaurants, and upscale hotels, including a five-star Hyatt. The inevitable peddlers, the fishermen, and even a resident cow relaxing on the sand accentuated the local color. To reach the shore, I had to step around cow dung, fortunately easy to spot on an otherwise pristine beach.

An optional tour of Goa’s historical discoveries took us further south to the village of Benaulim, where an artist has started a museum called Goa Chitra, meaning “Images of Goa.” Collected as a tribute to the artist’s ancestors, who lived close to the land, the original 200 items have grown to more than 4000 objects on display in the museum, which is set against the backdrop of an organic farm. The collection includes traditional farming tools, musical instruments, and Christian relics. The artist lives next door to the museum; the gardens, buildings, and displays bespeak an artist’s eye and hand at work. There is a museum shop, where I purchased a small painting of Ganesh, the god of good luck, son of Shiva and Parvati.

In the town of Quepem, lunch at the Palácio do Deão, an immaculately restored Portuguese mansion with two acres of lush gardens and a family-run restaurant, was indeed a treat. The owner gave us a tour of the beautifully preserved house, which had oyster shells in the windows and doors instead of glass and was furnished with antiques, including a four-post bed with a crisp white linen canopy scalloped along the edges. Lunch began with a fresh fruit drink, followed by appetizers of fried cheese balls, black olives, and sweet red peppers all skewered and dipped in warm butter sauce; fried minced prawn patties; and pumpkin soufflé. We continued with tomato soup with croutons, prawn or chicken curry, pork roast, grilled fish, brown rice, and baby greens. Dessert was a choice of crème caramel or chocolate cake. Our hosts, a couple, did all the cooking. The wife stayed in the kitchen while her husband served.

Menezes-Braganza mansion

The pièce de résistance was yet to come in the village of Chandor. Built in 1782, a vast, ornate mansion, the Menezes-Braganza, with original period furnishings, is still occupied by a 94-year-old seventh-generation descendant of a prominent Portuguese family. The second-floor rooms are furnished with gilt mirrors, four-poster beds, and numerous elegantly carved chairs. The ballroom has a blue and white painted zinc ceiling, Italian chandeliers, Belgian mirrors, Chinese porcelain vases, and a portrait of Anton Francesco Santana Pereira, the landowner who had the mansion built. At the time of independence in 1961, the government seized the land, allowing the family to keep the house. Across the street are the family mausoleum and church. No indoor photography is allowed. In addition to old mansions, the undulating land around Chandor is sprinkled with flashy new villas, built with money earned recently in the Middle East.

Besides trade and tourism, Goa’s wealth comes from mining iron ore, which helps to subsidize free medical care, including medicine. Compulsory education from the age of six through the first two years of college is also free. While men pay for university education, it is free for women, to make up for the years of neglect girls have suffered.

At the end of two full days, we departed from Goa. On the way to the airport, a view of the harbor, a hub for mineral exports, was my parting photo, though I continued shooting from the air, knowing the peaceful landscape below would soon give way to the skyscrapers of bustling Mumbai.

Mumbai (Bombay) comprises a cluster of seven islands and is the capital of the western state of Maharashtra, which sweeps from the Arabian Sea to the heart of peninsular India. It lies off the northern Konkan coast of the state, where the local tongue is Marathi. The name was officially changed from Bombay to Mumbai in 1995 to honor the patron goddess, Mumba Devi, worshipped by Koli fishermen, early inhabitants who settled here in 1138.

Mumbai was a colonial creation, made when the British gained a trading port as part of a dowry with the marriage of Portuguese Princess Catherine of Braganza to English King Charles II in 1662. From its beginnings as a group of boggy, malarial islands with a population of 10,000, the city started to attract Hindu rulers, Jewish and Parsi traders, and others in search of entrepreneurial opportunities, gradually growing into a densely populated cosmopolitan metropolis of 20 million. Mumbai is India’s largest city and is both the financial and cultural center of the country. It is the birthplace of Bollywood, where movies are made and where dreamers from all over Asia come to fulfill their fantasy of becoming movie stars.

Checking in

The Novotel Mumbai on Juhu Beach was our home for two nights. I was dazzled by a couple checking in along with us at the reception desk. Was this a couple just arriving on honeymoon or my first glimpse of Bombay’s high society? Regardless, I felt compelled to photograph the woman’s shimmering red dress with its low scooping back, so I took a picture from behind as a memento of my piqued curiosity. The mystique continued over dinner at a restaurant with African decor. It was apparent that Mumbai, as a city of migrants, was in a class of its own, its identity defined by internationalism rather than religion. Among the city’s unique features, our guide pointed out “grandparents’ parks,” where children may come with their grandparents, but not their parents.

Our full day of sightseeing began with a drive through vibrant congestion to see colonial Art Deco buildings, before a stop at the city’s Washing Quarters. These consist of rows of cubicles with access to water rented by the government to dhobi, men who wash clothes for a living. These men wash all day long, serving individuals, as well as commercial establishments such as hotels and restaurants. Above the cubicles, laundry hanging to dry stretched as far as the eye could see. When I asked what happened to laundry during the monsoon season, the answer was simple: “It takes longer to dry,” and “It is pressed.”

During the British Empire, architects blended Eastern and Western ideas, creating some of India’s finest Saracenic monuments, such as the Gateway of India, built in 1927 on the Colaba Peninsula. Until the age of airplanes, this was where ships and passengers coming to India arrived. Inspired by Gujarat architecture, the honey-colored triumphal welcoming arch, adorned with intricate carving, commemorates the visit of George V and Queen Mary to India in 1911, and is Mumbai’s best-known landmark and lookout point.

Taj Mahal Hotel and Gateway of India

The red-domed Taj Mahal Hotel stands beside the Gateway of India, overlooking the harbor. Built by Parsi trading tycoon Jamshtji Tata in 1903 and equipped with its own Turkish baths, it still caters to the rich of Mumbai, and was the target of terrorists arriving by sea in November 2008. Closed after that attack, the area has now been restored and is back in business. A tribute to Bombay’s resiliency, the grand area has recovered from the blasts and is once again a pole of attraction for people of every religion and language.

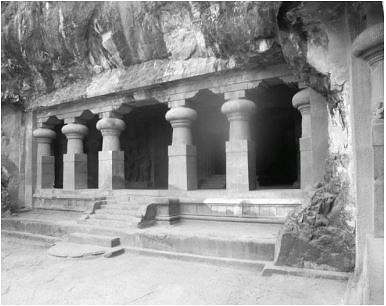

From the Gateway we took a ferry to Elephant Island, renamed by the Portuguese because of a carved elephant found in caves there. During the hour-long boat ride, vendors from the island’s three villages sold local crafts, including lapis jewelry. We rode an open air train along a causeway to save energy before climbing up to the caves. As we ascended the 120 steps lined with souvenir stalls, villagers tried to entice us with goods ranging from roasted corn to T-shirts to local crafts. Those not wishing to climb the steps to the temple have the option of being carried in a throne-like chair hoisted on the shoulders of two men.

Entrance to cave temple,

Elephant Island

Built between the 2nd century BC and the 12th century AD, the cave complex was started by Buddhists and, with the addition of elaborate carvings by Hindus, became one of India’s most important early temples; it is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Cut out of a projecting high basalt cliff, the temple is dedicated to Shiva. The central opening leads into a simple, dark hall held up by columns with capitals shaped like cushions. Monolithic carvings depict stories from the Mahabharata, showing Lord Shiva’s different aspects — half man, half woman in the Ardhanari pose, as both creator and destroyer; his powers multiplied by many arms; as killer of demons; as Yogi and Nataraja, Lord of the Dance; and with consort Parvati. The Lingum sanctuary, with its giant phallic symbol adorned with jasmine flowers, symbolizes fertility.

Following a visit to the magnificent temple complex, we returned to Mumbai to see yet another landmark building, Victoria Terminus railway station. Built in just nine years, from 1878 to 1887, this Gothic structure was the largest building project of its time and symbolized the progress of the British Empire, which established the first railways in India. The station is a grand, richly decorated, cathedral-like monument; the huge facade has projecting wings and is crowned by a colossal dome with a statue of Progress on top. A symbolic imperial lion and Indian tiger sit on top of the gate piers. The entire building is made of multicolored stones, decorative ironwork, marble, inlaid tiles, and exuberant sculpture. Students at the Bombay School of Art crafted the ironwork and decorative sculpture.

A contemporary landmark of a different kind is a 27-floor home built by India’s richest man at a reported cost of 2 billion dollars; he has a staff of 600 to serve his six family members. In stark contrast, we also drove by Mumbai’s slums, among largest in Asia, where Muslim tanners toil alongside Hindu potters. Because of Mumbai’s expansion, the slum neighborhood is no longer on the city’s fringe; it has now become a metropolitan economic zone, producing handbags, embroidered clothes, and pots in dark, dank rooms. This city of contrasts is also home to the Towers of Silence, where Zoroastrian Parsis offer the corpses of their dead for vultures to feed on. Occupying 55 acres of prime property on Malabar Hill, the Towers have separate slots for the bodies of men, women, and children.

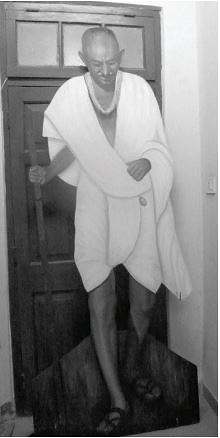

Portrait of Gandhi

in museum

During World War II, Mahatma Gandhi launched the Quit India Movement from Bombay, where he lived. His home, Mani Bhavan, is today the Gandhi Museum. Definitely worth a visit, this museum has large dioramas of Gandhi’s key actions towards realizing his dream of a united, independent India — resistance through non-violence; rejecting European clothes for the homespun cotton dhoti and shawl, symbolizing an autonomous, self-reliant India; belief in the equality of all; the 1930 adoption of a resolution demanding complete independence; the campaign of civil disobedience against the British monopoly of salt production; imprisonment in 1931; and fasting for peace at partition, when an estimated 5 million Hindus and Sikhs came into India, while a similar number of Muslims left for Pakistan amid bloodshed. On January 30, 1948, a Hindu extremist, angered by Gandhi’s tolerance for Muslims, assassinated him in Delhi. The museum shop has various books on Gandhi; I bought a compilation of his proverbs printed on handmade paper. This insightful visit gave me a deeper appreciation of the vast country that is India and for the unique cultural flavor of each of its states. I now felt ready to move on to Kolkata (Calcutta), known as the intellectual center of the country.

To begin the second leg of my tour, to Bhutan and North India, I flew from Delhi to Kolkata, capital of the eastern state of West Bengal. I arrived a day ahead of my tour group, allowing me extra time to explore India’s second largest city, with a population of 15 million, of whom 40% are Hindu, 20% Muslim, 10% Christian, and the remaining 30% Jain, Sikh, and Buddhist. My arrival coincided with preparations for a national census, which in India takes place over a two-week period. Teachers are recruited to assist with the census, forcing some schools to shut down. It is now against the law for doctors to reveal the sex of a child to parents in advance, as boys are still preferred by traditional families.

As I entered my fourth-floor room at the centrally located Park Hotel, drumming sounds led me to the view below — guests in glittering saris streamed in through a flower-adorned rectangular gateway flanked by two drummers, and walked down a path lined with waiters offering hors d’oeuvres. Realizing my room overlooked the courtyard of a wedding hall next door, I felt lucky that my three-night stay included a weekend, allowing me a bird’s-eye view of two weddings. While unpacking, I watched the merriment, which went on with lavish eating and drinking. When I looked out the window early the next morning, wedding hall staff was already busy cleaning up the sea of litter that had descended to the ground.

The Park Street Cemetery, listed among sights “not to be missed” in my guidebook, topped my exploration of colonial Kolkata. Map in hand, I started out from the hotel, quickly finding myself amid human misery. Every lame person seemed to have a place on the sidewalk, which also provided the means for the poor to eke out a living. Sitting on low stools or squatting down, they offered services — shaves, haircuts, cooking, dish washing, mending shoes, making keys, or minor repairs out of a small tool box — while children with small babies in their arms begged on street corners. Determined to find the cemetery, I continued walking with a heavy heart, understanding fully why Mother Teresa felt compelled to live and work in this city.

Given my surroundings, asking for directions to the cemetery was problematic. People on the street either did not understand English or did not know the word “cemetery.” Pedestrians who appeared educated drew a blank as to its whereabouts. Police sent me to a Christian cemetery, which turned out to be the wrong one; fortunately, the guard there was able to redirect me to the one I was looking for. The cemetery had been across the street from where I was all along, but locals did not have a clue as to its location.

On the corner of Park Street and Lower Circular Road sits the Park Street or Heritage Cemetery, opened in 1767. Beneath the shady avenues of cupolas, obelisks, pyramids, and classical mausoleums of all kinds lie the remains of men and women who built Calcutta out of a simple trading establishment. The architecture of the burial grounds recalls European grandeur, with graceful Roman cupolas and elegant Grecian urns. The cemetery contains many military graves of officers who were stationed in Calcutta. While life expectation was short for all, the tombstones indicate that some activities were particularly risky. Childbirth was the single main cause of adult female death. Infant mortality was very high. There is a reference to one mother having had fourteen children. The tombstones tell of many occupations, ranging from attorneys and judges to silversmiths and postmasters, including indigo planters and cattle breeders. These burial grounds are a repository of social history and a fascinating source of information.

In the afternoon I walked down Park Street in the opposite direction to see the Indian Museum on Nehru Street. Relatively speaking, this side of town appeared less impoverished. Still, I did walk through a crowded sidewalk lined with stalls, where goods from leather and terracotta to Kashmiri shawls were on display, catering to those out for a promenade, including women in saris of all shades and patterns, and Muslim men in white rimless caps and white panjabi or kurta. Dust, dirt, and traffic noise contributed to the mayhem. I pushed my way through the entrance gate of the imposing museum with its pillared Grecian-style facade, along with local visitors.

Chho mask of

goddess Durga

The country’s first national museum, founded in 1814, the Indian Museum holds exceptional archeological finds of ancient and medieval stone and metal sculptures from the Eastern Indian states of West Bengal, Assam, and Orissa. The first floor has a painting gallery, in addition to a courtyard with impressive stone carvings and temple statues. The second floor is a natural history gallery, with exhibitions dedicated to fossils, botany, and zoology. A climb of 150 steps leads to a mask gallery, featuring folk, temple dance, and festival masks from Eastern India and Bhutan. Lingering here the longest, I left with a book on the mask collection from the museum shop.

Back on the crowded sidewalk, I found respite this time behind the gates of the Oberoi Grand Hotel, built in 1911 and restored several times to hold on to its royal raj character. I felt grateful not to be stopped by security, although I was not a guest at the hotel. The surrounding splendor was an incredible contrast to the chaos on the street; the lobby dazzled with fragrant flower arrangements reaching upwards toward the chandeliers; long corridors overlooking a pool were enchanting, with peacock-shaped chairs in their alcoves. English visitors were having high tea by the pool, leading me to think they must frequent these places with a great deal of nostalgia.

Continuing down Nehru Avenue, I reached the West Bengal Emporium, a government-run shop featuring crafts of that state. Finding the establishment shuttered down, as it was Saturday afternoon, when government enterprises are closed, I walked to the Kashmir Emporium, a private concern run by a Kashmiri man. Due to Kashmiri demands for secession from India, business had slowed down back home — hence the move to Kolkata to promote Kashmiri handicrafts. I bought a wool vest displaying the region’s unique chain-stitch embroidery. As I tried to bargain down the $60 price, I was told that the woman who had made the vest had already been paid $20. I was saddened to hear how little this woman had earned in return for her unique skill. Not to miss out on a souvenir from West Bengal, I then purchased a camel skin bag with painted patterns at another shop.

After meeting my new tour group in the morning over breakfast, we left on a city tour, beginning at Victoria Memorial Hall, a symbol of British imperialism from 1757 to 1947. Built in 1921 and featuring a facade covered in Makrana marble from Jaipur, the structure is topped with a bronze figure of Victory; a striking Art Nouveau statue of Queen-Empress Victoria sits in front. Our Sunday visit coincided with a major Communist political rally, organized through the joint efforts of sixteen leftist parties to win the upcoming make-or-break election, having won the previous seven. The crowd, estimated at around 800,000, overflowed onto the immaculate open grounds of Victoria Hall, where people felt entitled to picnic or bathe in the protected lakes with careless abandon.

Similarly crowded was Mother Teresa’s home and mausoleum, known as “Motherhouse.” A pilgrimage place since Mother Teresa’s death in 1997, the sparsely furnished house, including her bedroom, is open to the public. People spend time meditating and praying in the chamber where her grave lies. Pamphlets on the premises provide chronological highlights of her life, from a devout childhood in Albania to joining the order of the Loreto Sisters in Dublin and arriving by ship in Calcutta in 1929 to join the Loreto convent. She received her calling in 1946 to start the “Missionaries of Charity” and exchanged her black Loreto habit for a white cotton sari with a blue border, dedicating her life to work in the Calcutta slums. In 1979 she received the Nobel Peace Prize.

Jain temple

A visit to a Jain temple was another learning experience. Jainism grew out of an uprising against the Hindu caste system by the merchant class in the 6th century BC. Jains, who are pacifists, are also vegetarian; they only eat vegetables that grow above ground, as pulling out a root kills the plant. Having achieved victory over class division, Jains, who are monotheists, have no ministers officiating at rituals, but instead have 24 leaders. They do not believe in marriage or family; they are baptized at the age of fifteen and lead solitary lives. The temple’s eclectic architectural style — Muslim, Hindu, and Rococo — delights the eye with ornate columns, inlaid mosaics of flowers and peacocks, and charming statues.

Although it was Sunday and many of the stalls were padlocked as owners attended the political rally, walking around the 6400 stalls in the booksellers’ section of Kolkata was an amazing experience. Young people eager to buy crowded in front of tiny shops crammed with books, in addition to those spread on the pavement, underscoring the Bengalis’ reputation as the “intelligentsia” of India. Kolkata boasts seven Nobel Laureates, including literary giant Rabindranath Tagore. It is also a city where wedding gifts include a book and a flower, plus anything else one chooses based on one’s social status. The literacy rate in Kolkata is 60% and rising.

Driving around colonial Kolkata, we arrived at Saint John’s Church, the oldest in the city, having been consecrated in 1787. Built of sandstone, the church is apparently modeled on the church of Saint Martin’s in the Fields in England. Inside are beautiful stained glass windows and a famous painting of the Last Supper. In the extensive compound of the church are other landmarks, notably the mausoleum of Job Charnock, founder of Calcutta; the monument is built in Saracenic style in lush surroundings.

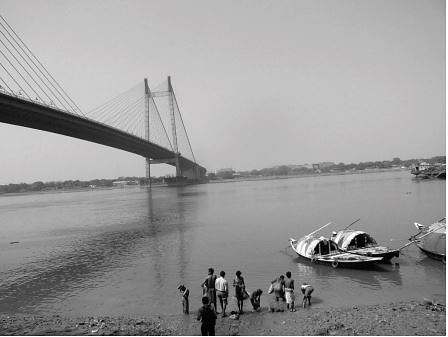

Imperial splendor continued to the Hooghly River, a branch of the Ganges. Ghats, stepped embankments, lined the eastern bank. Here people were bathing within view of the Vidyasagar Setu, a bridge spanning the river in a contemporary sweep of cables and airy elegance — a paean to the new face of Kolkata. As we made our way back through choked traffic, people on foot or riding on top of packed buses were heading for the Maidan, or Open Park, to attend the political rally. I took a photo, from my window, of people riding on the roof of a bus, prompting them to wave. My return wave was also a farewell to Kolkata. We left for Bhutan the next morning.

Vidyasagar Setu bridge and bathers