February 2007

The momentous occasion of my turning 70 prompted me to go to Peru. Machu Picchu, the ancient Incan site high in the mountains, beckoned as the place for a unique celebration. My friend Sumru accompanied me on the trip with Overseas Adventure Travel, which specializes in small group tours. Since this was my fifth trip with OAT, I knew we were in for great discovery.

My flight from Boston to Atlanta beat a predicted snowstorm by a day. Relieved to have made a smooth connection to Lima, I settled in for my seven-hour flight with my Insight Guide: Peru. The images in the book quickly transported me to Peru, 12 degrees south of the equator, where it was now summer. We landed in Lima past midnight. Despite the excitement of arrival, I was ready for bed. Since Lima is in the same time zone as Boston, I looked forward to a good night’s sleep free of jetlag.

Early in the morning I explored the hotel. It felt good to be in short sleeves and sandals. The rooms of the lovely colonial building faced a sun-splashed courtyard. The building sat back from the street in a garden of lush foliage, with decorative earthenware pots that added to its charm. The hotel Antigua Miraflores, named after the fashionable neighborhood it was in, would be our home for the next three nights.

Five of the fourteen people in our group were in Lima; the rest were to arrive late that evening from a pre-trip to the Amazon rain forest. Since I had been to the rain forest in Argentina, I had opted out of this extension. We met with our trip leader, Walter Torres, for a briefing. A handsome mestizo of native and Spanish heritage, he explained his English first name as a fashion of the time when he had been born.

Walter gave us some basic facts: A country with a population of 27 million, Peru is three times the size of California. 10% is coastland, 40% highlands, and the remaining 50% jungle. The Sierras, which run from north to south, separate the coast from the high plateau, where the majority of people live.

We went out for a stroll. Every block of the main street in Miraflores seemed to be populated with moneychangers. Business was brisk, as these men offered a better exchange rate than the banks. They examined each dollar to avoid counterfeit money, and rejected bills that looked worn. We strolled on, admiring African tulip trees with bright orange flowers. To compensate for the dry heat, their flowers store water, which squirts out when the bulbs are squeezed. Lima, 80 meters above sea level, has a desert climate. We stopped by a vendor’s cart stacked with gigantic avocados and mangoes. Walter introduced us to chirimoya (custard apple) — delicious.

Lunch was at an outdoor restaurant, where we enjoyed steamed vegetables, sea bass with potatoes, and mango custard. Given a choice between fish and meat, I often opted for fish. Of the world’s 6000 varieties of potatoes, 4000 grow in Peru. They accompany every meal and are used in every dish, including pasta. Peruvian potatoes come in every size and color, including yellow, black, and purple.

Our city tour began with a drive through the upper middle class neighborhood of San Isidro. We passed by embassies and casinos, including one with a Statue of Liberty as a signpost. Walter pointed out the soccer stadium, bastion of an institution as important as the Catholic Church throughout Peru. As we continued to the old part of the city, the scenery changed from leafy suburbs to beautiful colonial houses in decay. Many had “for rent” signs for as little as $60 a month. As the city has swelled with rural immigrants to a population of 8 million, hotels and businesses have taken flight to better run districts. The Plaza Mayor, colonial heart of the city, has been declared a cultural heritage site by UNESCO, which is restoring the vibrancy of the handsome square with a 17th-century bronze fountain in the middle. The buildings facing the square have been painted yellow-ochre, the main color used in the colonial period.

The Cathedral dominates the eastern side of the square, next door is the Archbishop’s Palace with an impressive wooden balcony, opposite stands City Hall, and police tanks guard the Government Palace on the northern side. Nearby, the Monastery of San Francisco faces a small paved square full of pigeons and vendors of votive offerings. The interior of this jewel of colonial Lima is decorated in the geometrical Andalusian Moorish style. Its carved wood-and-plaster ceiling, Spanish tiles, and religious paintings are outstanding. The building’s four levels of catacombs, which were used as Lima’s cemetery until 1810, contain hundreds of skulls and bones stored according to type. The National Museum of Anthropology and Archeology on Bolívar Square has a collection of pottery and textiles from the main cultures of ancient Peru — Chavin, Moche, Chimu, Tiahuanaco, Pucara, Paracas, Nazca, and Inca — laid out chronologically.

Our day ended with dinner and a folklore show. The buffet included both roasted and steamed giant corn kernels as appetizers, as well as the most famous Peruvian dish, ceviche — raw fish marinated in lime juice and hot peppers — accompanied by cold sweet potatoes. The folk dances showcased the richness of their origins; Castilian percussive footwork, African curved hip movements, and the acrobatic agility of natives in multicolored costumes were all most enjoyable. At the end the dancers recruited some of us to join them.

Sculpture at Larco Park

The next morning the full group met with Walter for another briefing. He introduced himself as a native of Cusco, where he had studied history. He spoke Spanish and Quechua, both official languages of Peru. We sampled the national drink, pisco sour, made of grape brandy, lime, egg white, sugar syrup, and bitters — most refreshing. Later a visit to Larco Park was unique. Known as Lovers’ Park, it has a large sculpture of a reclining couple kissing. In the park, which is a site for communal weddings, people were practicing for a kissing contest to be held later, as it was Valentine’s Day.

Lima has 43 neighborhoods. Traditional houses painted in deep ochre, blue, orange, yellow, and pistachio dot the landscape. They have flat rooftops, which are used for domestic animals, storage, water depots, and drying laundry. Barbed wire over walls of gardens bursting with African tulips and jacarandas is a vestige of the terrorist period. 52% of people in Peru live below the poverty line.

Villa El Salvador is a huge shanty town with a population of 800,000, making it the largest in the world. Started in 1971 by squatters fleeing the terrors of the Shining Path guerrilla movement in the mountains, it was recognized by the government in 1983 as an official district. We visited Santa Rosa, a community of 300 families, and were met by its president, who gave us a tour. Elected for two years, this 31-year-old woman was a mother of two and expecting a third. Every ten days three families take turns with kitchen responsibilities, in return for free food for a family of five. A communal kitchen provides soup and a main dish for residents, who pay around 75 cents. Every two days a water truck comes by, ringing a bell to signal it is time to replenish. People in this community, who drive taxis or shine shoes for a living, have created a functioning society, which even has its own penal rules. With government help they now have health clinics and schools running two shifts — 8 am – 1 pm and 1 – 6 pm. There are 52 children per class. Admiring human resilience and initiative, we left the staples we had brought — such as pasta, vegetable oil, soap, and shampoo — and thanked the president for her hospitality.

Our visit to the city’s bustling fish market provided great insight. Stalls were packed with varieties of seaweed, caviar, fish, clams, mussels, crabs, and shrimp. While vendors did not keep their products cold during the day, they shared a refrigerated area for overnight storage. After mining, fishing is Peru’s second major industry. Peruvians derive income from 7 million tons of anchovies caught annually. The prickly pear cactus fruit Walter treated us to on the way out of the market was the sweetest I had tasted.

In the afternoon the pace of life slowed down for siesta. Some shops closed till 4:30 pm. Taking advantage of our free time, Sumru and I visited Kuntur Huasi, a gallery for folk arts and crafts in Miraflores that a Peruvian friend in the States had recommended. One of the items I purchased here was a colorful retablo from the town of Ayacucho, known for the craft. A retablo is a decorated wooden box depicting scenes of folk life and overflowing with clay or plaster figures. The latter are mixed with boiled potato to keep them pliable. My retablo is of the corn harvest. Our hotel gift shop was an outlet for Fair Trade Products made in Peru. Purchases support women’s cooperatives that encourage traditional crafts. I purchased a cotton bag depicting hand-painted geometric designs by members of the Shipibo Tribe living in the eastern jungle. My other purchase was a sweater made from naturally dyed alpaca wool. I justified the cost of these items by their unique design and quality, and by the income the women’s cooperatives derive from them.

On the way to dinner we stopped by Lovers’ Park. Packed with kissing couples, the park was an incredible scene. The Costa Verde restaurant hosted our welcome dinner. All the tables were decked with red balloons for Valentine’s Day. In addition our table had an American flag. The first course, tiny scallops topped with Parmesan cheese and baked in their shells, was sensational. Sea bass with vegetables followed. Crepes with ice cream and fresh fruit ended an elegant meal.

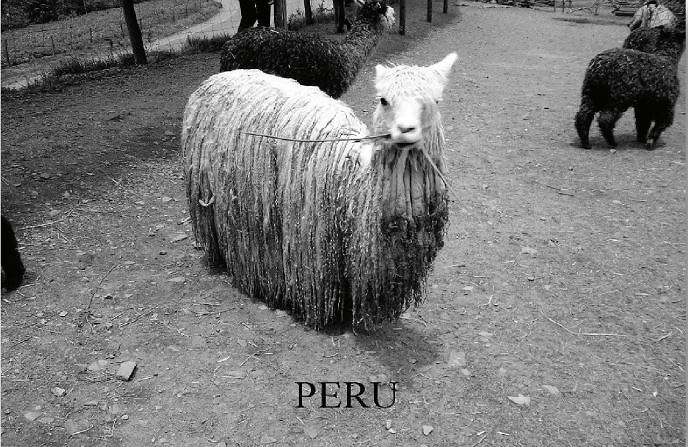

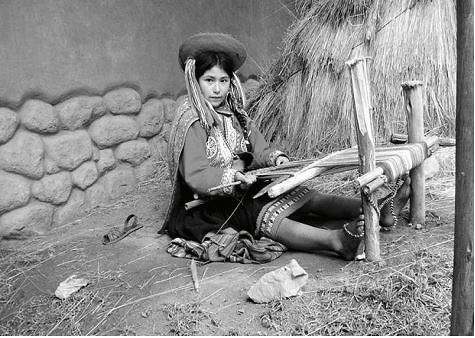

Young Andean weaver

Early in the morning we flew from Lima to the high Andes and landed in Cusco at 11,000 feet. To ease our transition to the high altitude, we drove to Sacred Valley for two nights before returning to Cusco. However, we had to climb up to an elevation of 12,200 feet and then began descending to the Valley. We passed mud brick houses, each of their roofs adorned with two ceramic bulls flanking a cross. Received as a gift upon building a new house, the bulls symbolize prosperity. Using ancient agricultural terraces, locals grow beans, grains, potatoes, and other tubers, as the Incas did. We stopped to snack on tamales wrapped in corn husks, and took pictures of grazing llamas. Of the four types of cameloids, the domestic llama is distinguished by its long neck. The others are the domestic alpaca, and the wild guanaco and vicuna.

Our lunch stop was at the ancient Incan city of Pisac. Andean musicians played, while we had quinoa soup enriched with peanut-shaped potatoes, grilled fish, and fruit salad. A climb to the top of the old city provided a sweeping view of the terraced mountainside. The stillness of the place and clarity of the air were unforgettable. We also visited cave tombs, where bodies were buried in fetal position to ensure rebirth. Our day ended with our arrival at the San Augustín Urubamba Hotel in Sacred Valley.

The next day we drove up the Urubamba Valley, excited about our trip on inflatable rafts. Large puppets representing godmothers hung from telephone wires or trees by homes. Since godmothers pledge to take care of children in case of need, they are honored with gifts and rituals on a special day every year. We were fortunate enough to have several opportunities to view large puppets commemorating this day.

We also stopped at the local Friday Market. Testimony to the mild climate and fertile soil of the valley, an abundance of fruit and vegetables lay on the ground, including mounds of corn; sacks with potatoes of every color; and heaps of cabbage, carrots, onions, avocados, mangoes, and peaches. Guinea pigs, rabbits, and chickens were a riotous sight. Roasted guinea pig is an Andean delicacy.

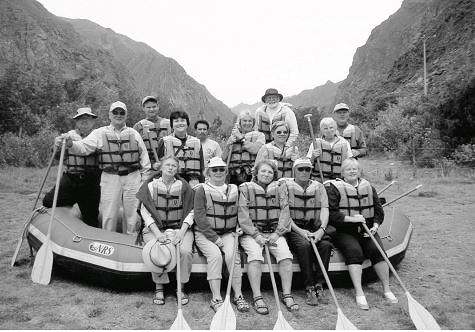

Ready for rafting

Our rafting trip on the Urubamba River was a wonderful excursion. Each donning a life jacket and carrying a paddle, we filed into two inflated boats. This first-time experience quickly taught me the importance of paddling in unison, especially when the water became rough. As we floated along the river, we were surrounded by steep hills. A network of hand-built terraces had transformed the side of the mountain into velvety arable land. Afterwards, while the boat crew fixed a picnic lunch, we visited the fortress and Incan holy site of Ollantaytambo, which includes the unfinished Temple of the Sun, made of large boulders.

On the way back we stopped at a chicharía, where locals enjoy chicha, a traditional homemade alcoholic brew. On the floor large urns covered with cloth stored the white, frothy corn beer. An acquired taste for Westerners, it is drunk in large quantities by Andeans at festivals or simply to get through the day. The non-alcoholic version, chicha morada, is made with purple maize.

The evening treat was a home-hosted dinner. Our farmer host and his seven-year-old twin daughters greeted us at the door. We met his wife and mother-in-law, as well as his houseguests, two young men who had traveled far to earn money for schoolbooks while harvesting corn. We sat at a long table covered with multiple colorful cloths, arranged diagonally. Hand-woven textiles adorned the walls; one served as a backdrop for a three-dimensional Christ figure. Otherwise the living-dining room was sparse. Our multiple course dinner began with a hearty soup and ended with a home-baked cake. Our host and his wife spoke limited English, and everyone else spoke only Quechua. Despite language limitations, we enjoyed the evening. The twins entertained us with English songs, such as Old MacDonald, which they had learned from other visitors. We each presented a gift before departing; my ballpoint pens were greatly appreciated.

A train ride to Machu Picchu on my birthday made it a very special day. On the way to the station in the town of Ollantaytambo we stopped at a Catholic cemetery. With the mountains as a backdrop, it was a beautiful spot. Tombs fashioned out of marble, with small chambers for memorabilia behind protective glass, constituted the affluent section. Crosses amidst flowers punctuated the plots of the modest part. Then we had a short tour of Ollantaytambo and its charming central square. In this best preserved of Incan towns, the old walls of the houses are still standing, and water runs through original channels in narrow streets.

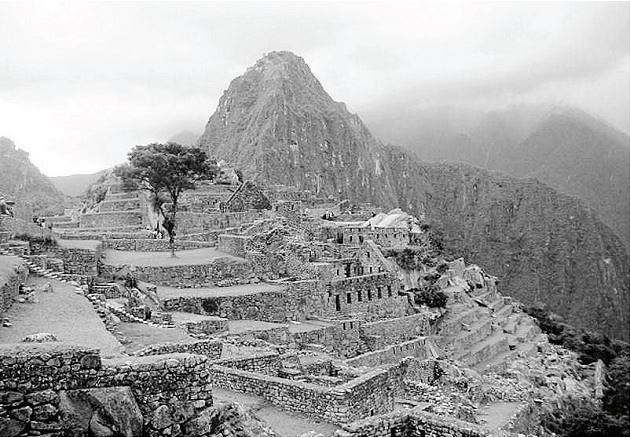

Ancient Incan city Machu Picchu

Run by Orient Express International, Vistadom is a rail service to the town of Aguas Calientes, 20 minutes from Machu Picchu by bus. The trip is $36 each way and takes 1½ hours. Our train pulled up to the platform at 10:20 am and, after a quick clean-up and snack replenishment, departed promptly at 10:30. It entered the gorge of the Urubamba River, wobbling on narrow tracks and rocking me to sleep. I dozed on and off, enjoying the scenic ride. We reached our destination in time for lunch at the hotel, situated right on the river. To have a relaxed pace at Machu Picchu, we spent two nights here. Traveling only with a night pack, we claimed our luggage later in Cusco.

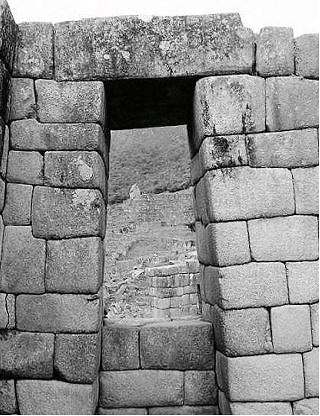

Incan wall construction

As soon as we cleared the crush of people at the entrance turnstiles and began climbing, the breathtaking beauty of Machu Picchu surrounded us. Under a cloudless sky, the ancient Incan city spread out between majestic peaks. Having escaped destruction by the Spanish as a deserted city, the archeological remains of this religious center of Incan life create a magical presence across the mountain landscape. The vast compound set within agricultural areas includes temples, royal enclosures, tapering towers, houses, storage huts, an observatory, and sacrificial sites. The walls are built from grayish white granite and fitted without mortar like a jigsaw puzzle. They have niches for idols and offerings. The trapezoid shape used for gates and windows provides structural tension between the stones, while also framing fantastic views. How these gigantic stones were cut by using only smaller sharp stones and then lifted is a mystery.

Unknown to the outside world until a farmer led Yale scholar Hiram Bingham here in 1911, Machu Picchu is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. As we walked among ruins, we spotted Andean birds, petted llamas, and identified wild flowers in full bloom. Descending for our return, I felt like a pilgrim at her destination. I could not have picked a more auspicious place for my birthday.

Back at the hotel Walter had a birthday surprise. He had ordered a cake with a single candle. When it was time to blow it out, it turned out to be a trick. Yet another new experience — at the age of 70 I learned about trick candles. Dinner was on our own that night. A few of us tried an Italian restaurant. Friends met on this trip treated me to dinner; I felt grateful for the camaraderie that we had quickly developed.

The next morning we rose early for a second look at Machu Picchu. It was raining, so Sumru and I had to let go of the option to climb the steep temple of Huayna Picchu, fearing slippery wet steps. Instead we joined hikers to the Sun Gate, a small Incan ruin set in a mountain pass above the city. The three-hour trip there and back on the partially stone-paved Inca Trail was an adventure in the fine rain. With clouds shrouding the distant mountain peaks, we walked above and through clouds moving near us. Orchids along the trail punctured the haze, with their intense blue and magenta colors brightening the mountainside. Friendly llamas appeared out of nowhere; the natural beauty all around was so amazing that I kept taking photos.

The trail ended at the Sun Gate, the site for sacrificial rites of the Inca, whose name means “son of the Sun.” On the shortest day of the year, heads of llamas were offered here to condors, the majestic Andean birds and “protectors” of the skies. The downhill return was slower than I had anticipated, due to wet ground. Although I had shoes with good traction, each step required caution. Those with hiking boots were able to pick up speed. At the gate we had our passports stamped as a souvenir. At lunch vegetable soup hit the spot, as I was quite chilled. After a cup of manzanilla (camomile) tea, a common beverage to finish a meal, I was all set to continue.

As luck would have it, it was the first day of Carnival week. Our train crew, some in masks, put on an entertaining fashion show on the ride back to Ollantaytambo. Then connecting to our bus, we headed for Cusco, stopping on the way at the small village of Chincero to visit a textile cooperative, where weavers introduced us to the traditional art of weaving on a back strap loom. Worn by the weaver, this portable loom provides a mobile workplace — at home, in the field, or at the market. Following a demonstration of how different types of wool — alpaca, llama, vicuna, and sheep — feel to the hand, we learned about the various processes of spinning, dying, and weaving. The wool of the vicuna is the finest and most expensive, because this rare animal can be shorn only about every third year and produces a very small amount of wool. Alpacas can only be shorn on alternate years and yield a greater amount of wool, which is finer than that of the llama.

As we came upon Carnival festivities along our way, we stepped out of the bus to view them. Women in layered skirts and men in knitted hats danced around trees festooned with balloons and gifts. Celebrants enjoyed spraying one another with shaving cream or drenching each other with buckets of water. The roadside fields turned into a patchwork of varying shades of green as we continued. We passed by potato fields with purple and white flowers, and others with maize, quinoa, and broad beans. At the end of an adventurous day we finally arrived in Cusco. After a delicious grilled chicken dinner with a sliced avocado appetizer at the hotel, I dropped off to sleep.

Our two full days in Cusco began with a dramatic account of Peru’s struggle with terrorists from 1980 to 1994. Two police officers who had been on active duty during those years took turns introducing us to recent Peruvian history: Members of the educated elite provided the leadership of two terrorist groups, the Shining Path and Tupac Amaru, named after a revolutionary hero who had fought the Spanish. These leaders hoped for a new Communist country after visiting Russia, China, and Cuba. Their armed groups terrorized the mountain people first and then moved toward Lima, dynamiting police stations and government buildings. Also targeting affluent civilians, they killed 70,000 people until the leaders were captured in 1992. They are all in prison, including American Laurie Berenson. In 2002 President Fujimori appointed a commission to look into the cause of the terrorist activity. The findings highlighted economic differences between rich and poor, stressing the lack of jobs. The ensuing process of national reconciliation emphasized education, human rights, and building infrastructure, including roads. Peru has taken giant steps to improve its economy, of which tourism is a major part.

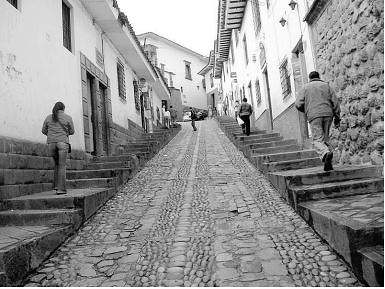

Cobblestone street in Cusco

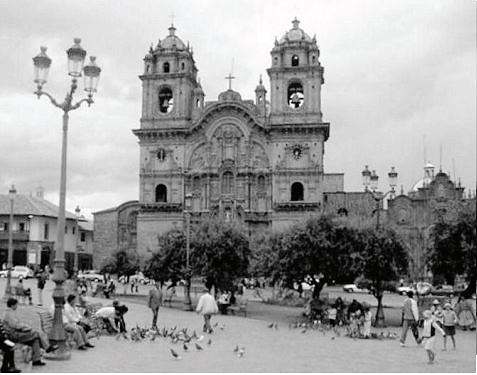

Cathedral on Colonial Square

Cusco was the capital of the Incan Empire, which ruled for over 200 years. 1 million people live in greater Cusco — 300,000 of them in the city proper. It is a picturesque city of red tile roofs stacked against the surrounding hills. To reach their homes people often climb more than 400 sidewalk stairs flanking narrow cobblestone streets. Adobe buildings with ornately carved blue and green wooden balconies face the town’s colonial square, dominated by the Cathedral, which mixes Spanish Renaissance architecture with native stonework. The Cathedral has examples of paintings from the Cusco School, a 17th-century movement that used rich, dark colors and blended European and indigenous motifs. A painting of the Last Supper depicts Christ and his apostles dining on roast guinea pig and hot peppers. Cusco has South America’s oldest university, built in 1692.

To the south of the square is the Qoricancha Sun Temple, the main Incan place of worship. Now the Church of Santo Domingo, the temple is a great work of Incan architecture featuring fitted mortarless stone walls and trapezoid niches. These walls were once covered with 700 sheets of gold studded with emeralds and turquoise. Windows were constructed so that sunlight would reflect off the precious metals. To eradicate every trace of pagan culture and in their thirst for gold, the Spanish melted down all the gold in the temple. Nearby is Merced Church, which contains the remains of some of the Spanish conquistadors. It has an adjoining monastery and a museum of religious art. The latter has gold and silver altarpieces, the most ostentatious of which is a jewel-studded solid gold monstrance (a vessel for displaying sacramental bread).

Following lunch at a pollería (a chicken diner), where the group enjoyed spit-roasted chicken, Sumru and I spent our free time exploring museums. The Archeological Museum was well worth the visit for its collection of pottery, textiles, and gold artifacts. A delightful discovery was the Folk Art Museum, where popular themes were interpreted in fanciful ways, such as a hand-crocheted depiction of the Last Supper.

At the Cusco Center for Native Dances, we watched traditionally garbed performers in foot-stomping dances to the accompaniment of reed flutes, panpipes, violin, accordion, and drums. Inspired by early agricultural rites, these dances temporarily made us forget that the Incas had lost in their confrontation with the Spanish. Dinner at Cicciolina’s — an upscale Italian restaurant expensive by Peruvian standards, but worth every dollar spent — topped off the evening.

In the morning we stocked up at an open air market in anticipation of our visit to a curandero, a shaman healer practicing traditional folk medicine. In pairs, we set out to locate items assigned to us by their Spanish names. As soon as Sumru and I mentioned the name chuta to a vendor, we were sent to a stall diagonally across. Delighted with our early discovery, we bought a round loaf of chuta, Cusco’s typical flatbread. Mingling with shoppers wearing Incan sandals made of used tires and carrying babies in embroidered bundles on their backs, our group completed their purchases for the curandero — a cow’s head, beans, bunches of giant radishes, fruit, coffee, and bread.

On our way to the healer we drove into the hills surrounding Cusco. The fragrance of eucalyptus trees, imported from Australia, permeated the bus. We stopped at an important pre-Incan and Incan site. The massive Sacsayhuamán archeological site sits on a hilltop within a national park overlooking the city. The largest stone of this ancient complex weighs 128 tons. We enjoyed panoramic views as we walked about temples and sites for offerings to the gods.

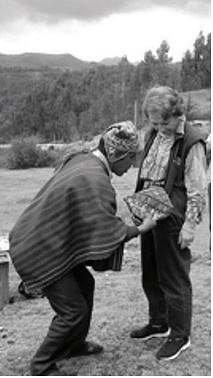

My turn with

the healer

The curandero was waiting for us on top of a hill by the mountain. Seated in a semicircle facing him, we participated in a ceremony for the health of our group. Using the energy of Apus, a sacred mountain, and Pacha Mama, Mother Earth, he prepared a concoction by giving us each three leaves from the coca plant, regarded as the combiner of all energy. We “blessed” the leaves by blowing on them toward the mountain, and returned them. Arranging the leaves in the center of a square cloth, the healer added an assortment of ingredients, such as grains and herbs, shaping the mixture into a gentle mound. The “blessing” was followed by a sprinkling of rice and small bits of sweets along the edges of the mound, which was finally flattened and bundled into a small rectangular package in an embroidered cloth. Then we individually volunteered for treatment. I stood in front of the curandero pointing to my hands, as they are very sensitive to cold. Starting at my head he moved the package slowly all over my body with full concentration on my hands. Believing at least in the psychological effect of our treatment, we said goodbye in gratitude, leaving the staples we had brought along.

Lunch afterwards included small dishes of corn and broad beans with sauce, quinoa-based Andean soup, and succulent lake trout. The waiter passed around a roasted guinea pig on a platter for us to sample this delicacy, which tastes like something between a chicken and a rabbit. Agave ice cream topped off the meal. On our way back to Cusco we stopped at a silver factory, where we watched artisans melt down ore and shape it into threads and sheets of silver for crafting jewelry studded with semiprecious stones and shells. I bought a silver ring here at the modest price of $15. Our next visit was to an alpaca shop, where I acquired a scarf, which kept me warm for the rest of the trip. However, my most treasured purchases were two ceramic plates. Inspired by the pottery culture of ancient civilizations, local artisans continue the tradition. One of my acquisitions, a concave plate, supports the sculptured head of a duck; the other is a black plate made by reducing the oxygen level during firing. Its bold white geometric patterns make it an attractive wall hanging.

The next day the six of us continuing on an extension trip bade farewell to those returning home, and headed south on a ten-hour journey to Puno and Lake Titicaca near the Bolivian border. The 380-kilometer trip on the two-lane Pan American Highway, though lengthy, was both scenic and interesting, with stops at numerous sites. During our gentle climb southward we caught glimpses of Incan walls alternating with cabbage, corn, and onion fields. Since the 1968 agricultural reform, Peruvian law has stated that “land must belong to those who work it.” Police stopped us a few times and checked under the hood of our van to make sure our engine was not stolen. In one instance they even had to call Cusco to authenticate the vehicle’s registration papers.

The route from Cusco to Puno is lined with towns, each with a specialty of its own. We passed by one famed for its black magic and another for its brick-oven-roasted guinea pig, a delicacy eaten on special occasions. House fronts, sprinkled with confetti for Carnival, signaled good luck.

The town of Oropesa, whose name means “gold weight,” is renowned for its chuta wheat bread, made with pork fat. Every home has its own bread oven, its bricks strengthened by women’s hair in the mud mixture; the ovens burn eucalyptus wood. We stocked up on bread for the hotel and ate one loaf on the spot. Finding alternatives to agriculture in the harsh mountain terrain, towns have developed cottage industries. We passed by one town where families specialized in handmade roof tiles. The semicylindrical tiles are fitted together to construct a roof for about $150.

Andahuaylillas is a charming little village with cobblestone roads and colonial houses. It is renowned for its ornate 17th-century Jesuit church. With its gilded altar, fine frescoes and paintings framed in gold leaf, the village church resembles a cathedral in its sumptuous decor. A painting in the Cusco School style depicts the Holy Family in native costume. Sculptured saints are taken out of the church for religious processions. Votive candles offer choices — white for peace, green for prosperity, and red for love. People come from as far as Lima to marry here.

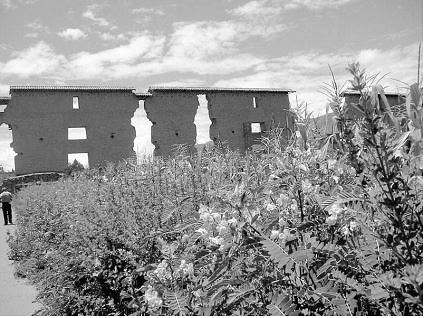

Incan temple ruins at Racchi San Pedro

Following the Inca Trail southward, we passed workers constructing a road to Brazil, Peru’s main trading partner, selling technology in exchange for agricultural produce. Roadside buildings served as billboards for political campaigns. Women, whose hat styles changed from one area to the next, carried big bundles on their backs to far destinations. Racchi San Pedro is known for the ruins of the largest Incan temple, Viracocha. The site sits amidst fields of corn, broad beans, peas, and tarwi bean plants with blue and white flowers. Round storage towers with thatched roofs complement the rural setting. Built in 1400, the temple is of stone and adobe. Birds rest in its niches, once used for offerings. Suddenly a loud gunshot pierced the air, killing a woodpecker, a victim of the temple guard. This bucolic land is also known for its natural waters, sought after for stomach ailments. From a vendor I bought two strings of bright orange seeds from the jungle for good luck.

Before our climb to La Raya we had a picnic lunch break at Sicuani, traditionally known as a land of writers and poets. Then we drove by a small volcano with hot springs, arriving at La Raya, the highest point of the highway at 14,000 feet and the demarcation point between the Cusco and Puno regions. We stopped for a panoramic view of the high plateau. Herds of alpacas and vicunas, bred by the animal husbandry departments of local universities, dotted the landscape. Vendors in colorful native garb lined a wall, with their wares on makeshift stalls. My irresistible purchase was a pair of $10 alpaca slippers, which I have been wearing since arriving home.

Descending to the high plains, we saw the Peru Rail speeding by on its way from Puno to Cusco. Excitedly, we spotted the beginning of the Amazon River coming down the mountain peak. We stopped in Pucara, where famous ceramic bulls that adorn every house are crafted. A tradition brought by the Spanish, these bulls are believed to bring good luck. As instructed by Walter, I gave a bag of soap and shampoo to an old woman in exchange for permission to take her photo. As such items are hard to come by for the poor, they are considered as good as cash. Set back from the road were uniform outdoor units installed by each mud brick house. Distinct with their deep green color and thin air vents, these were toilets that had been donated to all hill country residents by former President Fujimori.

Dancing around

the festival tree

Carnival festivities entertained us in the village of Tijuana, where celebrants in bright red costumes danced by the roadside. Our final stop before reaching Puno was Juliaca, the industrial center of the region, with a population of 250,000. People danced around a tree festooned with balloons, to the beat of drums. I went daringly close to take pictures and was sprayed with shaving cream — a common Carnival prank. Feeling lucky that I had not had a bucket of water thrown at me, I returned to the van. People in this part of Peru are related to Bolivians culturally and speak Aymara. They live in unfinished houses, both because of a lack of money, and to avoid paying taxes. We took a toll road for the final stretch of our trip, passing by a cement factory releasing clouds of billowing smoke.

Lake Titicaca appeared before we reached Puno, our final destination. Considered the world’s highest navigable lake at 12,725 feet, it stretched out to Bolivia in the distance with its turquoise waters. Eager to settle in after a long day, we drove straight to our hotel in Chucioto, 18 kilometers outside of Puno on the lake. The decor of the Taypikala Hotel reflected the richness of the region’s folk art. Beautifully framed hand-loomed textiles and knitted hats adorned the walls; table-size replicas of totora reed boats fueled my anticipation of what was yet to come. I settled near the fireplace to enjoy coca tea, our welcome drink. Following a dinner of kingfish from the lake and quinoa flan, I called it a day.

In the morning our local guide taught us a few words in Aymara — “Kamisaraki” (How are you), “valiki” (I’m fine), and “Yuspara” (Thank you). We used these words, accompanied by a handshake, consistently in greeting and thanking villagers during our visits. The day’s excursion began at our home base in Chucioto with its notable Incan fertility temple, an enclosure of giant stone phalluses — some broken, some intact. Peruvians practice a composite religion that combines elements of Catholicism and pre-Columbian pagan rites. The roof of the nearby Catholic Church has two phalluses, one of which has been knocked down by lightning.

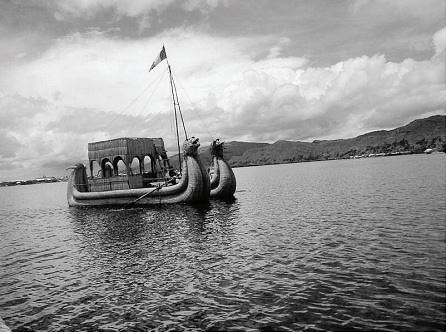

Totora reed boat

Lake Titicaca, which means “wild cat” in Incan, derives its name from its shape, which looks like a puma. For the Inca the puma represented this world, the condor the heavens, and the snake the underworld, with the three together creating harmony. According to legend, a pair of gods rose from the waters of Lake Titicaca to found the Inca Empire. The lake is 103 miles long, 37 miles wide, and 900 feet deep. During the rainy season the water rises 7-8 feet. Surrounded by the Andes, the lake never freezes, and its temperature varies between 45 and 50º F. 25 freshwater rivers, seven of which are quite big, pour into the lake. The harbor is Puno, a city of 170,000, where fishing is the main industry. The lake has many trout farms, some of which are owned by Chileans.

Our visit to Copamaya, where we had lunch, gave us an insight into rural customs. In this village all women knit and weave. Children and young girls wear knitted caps; married women wear bowler hats. Single women wear their hair in two long braids down their back; married women connect the braids at the ends to indicate their attachment. Women buy ornamental hair for a fluffy look at the ends of their braids, or to split them into multiple thin ones.

For lunch we cooked potatoes by burying them in a mound of hot rocks over burning dung. 20 minutes later, we peeled and ate them with our choice of clay or chili sauce. From a spread of earthenware pots we helped ourselves to broad beans, with or without shells; fried cheese; and rings made from quinoa batter. Our hosts sat separately, women and children squatting or sitting on the ground, men on low benches against a wall, as is the custom in the Andes. After lunch our hosts dressed the women from our group in knitted hats, embroidered jackets, and layered skirts. In our rural identity, we paired up with locals, joining hands and dancing to the rhythms of village tunes. General merriment ensued.

On the way back we heard the infectious rhythms of a band, so we made an impromptu stop. In a roped-off area by the town hall, dance groups were rehearsing for a competition. Except on the side reserved for the jurors, crowds surrounded the performance area. Spotting us in the throng, the mayor came over to welcome us. We declined his invitation to join him in the VIP section and preferred to watch standing. We watched one group of 300 dancers, the minimum number required for the competition. The jury, all male with one exception, included the mayor; the prize was two big drums and a six-pack of large bottles of soft drink. I took a photo of the mayor with his secretary — him in Western attire and her in native dress.

People in the Andes seem to live to dance. During Carnival dancing even stops traffic. On our way back to Puno, dancers on the street stopped us; we had no choice but to join the spectators lining the street, while musicians on the slopes kept the rhythms going for the foot-stomping couples. Finally impatient truck drivers, loaded with goods from Chile, made their way through the dancers, also helping us pass. Puno is Peru’s folklore center, known to have over 300 different ethnic dances. In addition, it has an array of handicrafts and festivals.

Upon arriving at the hotel, I found a nice surprise waiting for me. In my room were a bottle of red Peruvian wine and a basket of fresh fruit. The accompanying note thanked me for traveling again with OAT. I was glad for this recognition of my passion for adventure travel. The highlight of dinner at the hotel was wholesome criolla soup; slightly spiced, it contained beef, noodles, milk, egg, and herbs — delicious.

In the morning we departed for the Bolivian border. On the way we passed by large rocks that to native imagination evoke animals — snail, elephant, guinea pig, and rabbit. We climbed the back of a long “snake,” walking the entire length from its tail and stopping midway to meditate at a sacred spot where natives blow coca leaves to the surrounding mountains. Since the snake sheds its skin, it is a sacred animal for the Aymara, who believe in reincarnation. Their beliefs include layers of superstition, such as burying the dead in their backyard to ensure protection by ancestors.

Over the fields we spotted Andean black ibises and hummingbirds looking for worms. We continued our ride by the side of the lake, which is divided almost midway, with 60% in Peru and 40% in Bolivia. The coast guards of both countries monitor the border, marked by an imaginary line between two mountain peaks. Trout farms dot the lake, as wild trout are eaten by kingfishers. Andean gulls hover over the lake to hunt for trout as well.

Stopping at the village of Pomata, which means “house of Puma,” we visited the granite church of Santiago Apostol. Built in 1567, this church is dedicated to Saint James, who offers protection from lightning. During thunderstorms people come here to pray. The ceiling domes of the church are adorned with native figures. Passing by grazing alpacas, we arrived at the border of Bolivia, which was Upper Peru until 175 years ago. It is in a time zone one hour ahead of Peru. Border control is strict, due to cheaper goods being smuggled from Bolivia into Peru. However, the police accept bribes. Peruvians have to have a special sticker in their passports indicating that they have voted; otherwise they may not travel outside the country.

Copacabana, Bolivia

Copacabana is a pleasant town of 15,000 Aymara-speaking people on the Bolivian side of the lake. It is famous for its Cathedral, which contains a 16th-century carved wooden figure of the Virgin of Copacabana, the Christian guardian of the lake. Except during Mass, the statue stands with its back to the congregation, and faces the lake so that it can keep an eye out for an approaching storm. The door of the Cathedral has elaborately carved wood panels that show laborers during construction. As a religious center for Catholics who come to express wishes, the Cathedral is a busy place. Outside vendor stalls are stacked with goods that might help fulfill a wish, including small models of houses, cars, diplomas, and suitcases. A long, narrow room with walls covered in candle wax is filled with flickering votives of various colors.

Houses in town were decorated with flowers and flags for Carnival. Families take turns paying for festivities in their neighborhoods. We drove to a lookout at 13,000 feet, which gave us a spectacular view over stone walls and terraced hills. We enjoyed lunch in a garden — lake trout followed by a typical dish with minced meat, onions, tomatoes, and egg. Potatoes left to freeze outdoors overnight constituted “ice cream.” There are 49 ethnic groups in Bolivia, with variations in beliefs. Some eat salt and chili peppers to cleanse themselves of sins; others make pilgrimages to sacred sites.

A boat trip took us to one such sacred site, an island with a frog-shaped rock jutting over the lake. In February people make a pilgrimage to festoon the frog and make a wish. A shaman met us as we disembarked and helped us individually to participate in the ritual. I stood at the bluff and blew toward the mountains as I made a wish. Then the shaman sprinkled the head of the frog rock with a bit of alcohol, handing me a bottle of “champagne” (sparkling cider) to throw into the frog’s mouth. Breaking the bottle on the first blow makes wishes come true; it was not my lucky day.

On our way back to Peru we crossed the border along with several people wearing eye patches. They had come to Bolivia to have eye surgery. Based on an agreement among Cuba, Ecuador, and Venezuela, people may travel to Bolivia for free eye surgery by Cuban doctors, 20 of whom practice in Copacabana. There was much frenzy along the road, as Carnival was nearing its end. In the last three days a tree is chopped down, to be erected at a site conducive to merrymaking. The man whose final blow topples the tree is considered lucky. Once the tree is decorated, there is continuous dancing and drinking around it.

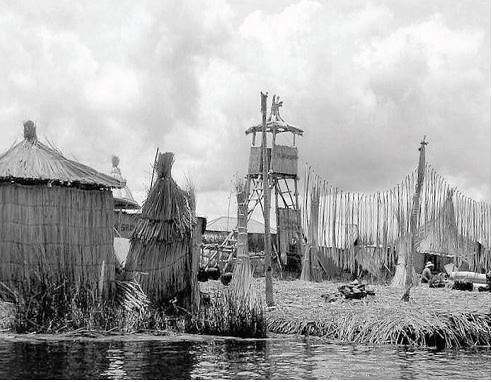

Uros floating island

On our final day in Puno it rained hard. Nonetheless, we headed out to the Uros Islands, where the Uros Indians live on “floating” islands made of reeds that grow in the lake’s shallow waters. The boat docked at one of the islands, where we had a demonstration of reed construction. Men dive for the spongy part of the roots, which they then strengthen by putting ropes through big square chunks. After tying these together, the cut reeds are placed on top in a criss-cross fashion. Once this foundation is set, houses, also made of reeds, are erected. Building this way avoids paying taxes. Residents catch fish by stretching nets between sections of the islands, and hunt birds with self-made guns from metal pipes and balls of pellets.

Fortunately the rain cleared up, so that we could walk around the craft displays. I bought a cushion embroidered in blue and depicting a mother with her baby bundled on her back in a boat, a colorful mobile of birds made of reeds, and a small reed boat called a “balsa.” These are souvenirs made for the tourist market; poverty makes the islanders take a hard-sell approach. My gift to them was a bag of fresh fruit, as their diet is very basic. Walking around, we enjoyed the island’s fauna — blue-beaked Andean ducks (small ducks that hatch big eggs), herons, cormorants, and great egrets. Women drink cormorant blood to counter the effects of menopause. We navigated back to Puno, visited a natural history museum, walked through a market admiring cotton prints, and settled down to a lunch featuring alpaca.

Afterwards we rode to Sillustani, set on a peninsula in Lake Ayumara. At 13,000 feet this was a magical place, breathtaking in every direction. Here stand pre-Incan ruins called “chullpas” — funeral towers, where the Colla tribe buried their elite. These cone-shaped tombs are made of huge stones, which are bigger at the top than at the bottom. They provide a womb-like space for mummies, who were buried with their valuable possessions within the inner walls. The Spanish have ruined these walls looking for gold.

A village home on the peninsula was a final opportunity to pet llamas and to view alpacas and guinea pigs. We snacked on baked potatoes with clay sauce and homemade cheese. I purchased my last souvenir, a small pair of ceramic bulls to bring me good luck. Making our way through festive crowds, we arrived at the hotel to pack for the trip home. For our farewell dinner Walter had arranged a feast, which began with pisco sour and continued with sampler plates of steamed vegetables, tomatoes with pressed cucumbers, mashed and sweet potatoes, grilled beef, roast chicken, apple pudding, and ice cream.

On the way to the airport in Juliaca, we drove through the town market. At 7:15 am the place was bustling. Sidewalks were crowded with sacks of produce and cages of guinea pigs and chickens, while their owners enjoyed steaming bowls of noodle or quinoa soup to temper the morning chill. It was the final Sunday of Carnival, and consistent rhythms of bands filled the central square. Colorful streamers on trees and paper flags stretched across narrow streets brightened the run-down look of unfinished brick buildings.

Our flight to Lima had a stopover in Cusco. Although we were supposed to continue, we were asked to disembark due to mechanical problems. We had to wait three hours for another flight that had space for the 6 people in our group. We felt fortunate to have Walter, who dealt with the hassle of locating space among many passengers facing the same predicament. As a result of the shuffle, my luggage did not show up on the carrousel in Lima. A phone call to Juliaca assured me that it would come on the next flight. Much relieved, I left the airport, knowing I would be back to claim my luggage in time for my overnight flight to Atlanta. Our remaining time in Lima did not allow for new insights, as it was Sunday, and in this Catholic town most everything, including restaurants, closed by 6 pm. Nevertheless, Sumru and I did enjoy a final stroll in the park.

The airport procedures were smooth, other than the fact that my bottle of Peruvian wine was confiscated by security. Disappointed, I tried to make a case that the bottle was sealed. In response, I was reminded that “no liquid” is my country’s regulation, not Peru’s. On the flight back I reread my guidebook to fully absorb Peru’s varied natural beauty and legacy of rich cultures. The mountains, deserts, lakes, and coastline, combined with remnants of ancient civilizations, give the country a breathtaking landscape. It has some of the world’s most spectacular scenery and fascinating native cultures. As Peru increasingly faces the realities of industrialization, in addition to the challenges of increasing rural exodus, urbanization, illiteracy, and poverty, it also runs the risk of eroding its wonderful traditions and folk culture. As is often the case, modernity and tradition are a costly trade-off. Will the shaman’s powers manage to keep the two in balance?