February 2011

Royal Bhutan Airlines transported us from Paro to Delhi, with a brief stopover in Katmandu; we had to set our watches back by fifteen minutes between each city. Rajesh, our trip leader, met us at the airport, announcing that it had just started to rain. Still, the 30° C temperature felt good after the high hills of the Himalayas, and the five-star Suryaa New Delhi, with all its amenities, was like a home away from home and included a local novelty — a large-screen outdoor TV in the market next door.

Our group grew to fifteen with the addition of eight people for the main trip. Following a briefing by Rajesh, we began a city tour with a drive through the colonial part of the city, specially built when King George V decided to move the capital of British India from Calcutta to Delhi in 1911. British architect Edwin Lutyens designed the new capital, called New Delhi, on Raisina Hill, which is the political center of today’s India.

Raj Pat (King’s Road) sweeps down by Sansad Bhavan, the circular Parliament House, and past India Gate, a tribute to the 90,000 Indian soldiers who died in World War I and the Afghan War of 1919. Further along is a sandstone pavilion which once held a statue of George V, but now stands empty. Surrounding the pavilion are grand former palaces. Along Raj Pat are other civic buildings such as the National Archives and National Museum. Government buildings showing imperial classical facades with Indian details dot Raisina Hill.

A bicycle rickshaw ride around Old Delhi was an experience. We rode down Chadni Chowk, the main street of the historic bustling market, dodging other rickshaws, motorcycles, bicycles, and pedestrians balancing loads on their heads, some with mouth masks against pollution. Muslims with brimless hats, Sikhs with turbans, men in dhotis, and women in saris or waist-length head covers mingled on the sidewalks, underscoring India’s motto: “Unity in Diversity.” School children with backpacks lined up by ice cream carts, while others crowded around street food, enticed by the aromas. A MacDonald’s graced the street level of a cinema complex, with large billboards advertising movies above.

Wending our way through the narrow side streets of this fascinating city within a city, we passed by tiny boxlike stores filled from floor to ceiling with bridal saris, glittering groom’s turbans, and jewelry; other streets specialized in spices with sackfuls of tamarind, ginger, and chilies weighed out on large iron scales. The view above was equally arresting, with an ancient-looking tangle of cables crossing among buildings and over streets. Old Delhi Town Hall (1860), with a statue in front, was impressive. Resident monkeys clambering on railings of balconies completed the amazing spectacle.

Jama Masjid

Our rickshaw ride ended at the Jama Masjid, India’s largest mosque, built in 1656 by Shah Jahan, builder of the Taj Mahal. Donning long, colorful robes as required, although none of us had exposed arms or legs, and leaving our shoes with an attendant at the top of a great stairway, we walked into the courtyard behind walls separating the sacred area from the street. Inspired by the Prophet Mohammed’s house in Medina, the sandstone mosque has a large courtyard with a vaulted hall at one end, and a single minaret, where a muezzin summons the faithful to prayer. The columns are inlaid with semiprecious stones and brass; the courtyard pool serves as a place for ablution before prayer facing the central mihrab (niche) of the hall and indicating the direction of Mecca. The mimbar (pulpit) is for the sermon, given during communal midday prayers on Friday, the Muslim holy day. The courtyard pool, in addition to being a place for ablution, serves as a place to gather and socialize. Sitting along its marble edge, young people chatted on cell phones, while women and men, in separate groups, conversed and had a good time.

Making our way through the crowds and vendors around the mosque, we returned to the bus for a ride to the Raj Ghat to visit the Gandhi Memorial. We had to drive through streets lined with shops selling spare parts. Cars left unattended are stolen, dismantled, and sold for parts. 5000 new cars and 7500 new motorcycles are released onto streets of Delhi each month; the fuel of choice is compressed natural gas (CNG) or diesel, both cheaper than petroleum. Therefore, smog is a major problem, especially when the temperature drops in the evening, keeping the smog close to the ground.

Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated on January 30, 1948 in the market by a Hindu extremist, angered by Gandhi’s tolerance for Muslims; the father of the nation was cremated at the nearby Raj Ghat, a stepped embankment by the river. A marble memorial platform marks the spot where his ashes are buried. A walled square garden provides an oasis of peace surrounding the memorial, which has a flame at the head and a flower container at the foot. The Raj Ghat is the most visited site in Delhi.

Our evening meal was one of the tastiest of the trip. Although I had had some of the dishes before, they were prepared in different ways. Tikka — chunks of boneless chicken cooked in a clay oven, or tandour — had been marinated in spiced yogurt, which made it very tender. It was served with basmati rice. Gulab jamun — deep-fried balls of cheese dipped in syrup and sprinkled with pistachios — was served warm with buffalo milk ice cream, making for a great combination.

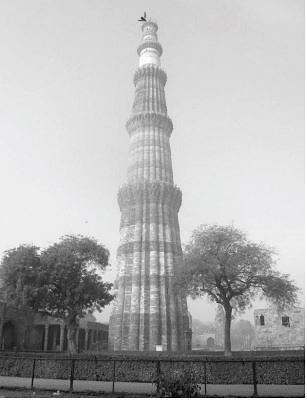

Qutb Minar

Another one of Delhi’s famed Muslim sites is the Qutb complex, including the Qutb Minar, the tallest minaret in India at 238 feet, with 379 steps to the top. It was built in the 13th century as a victory tower and is attached to the Qumwat-ul-Islam Mosque. Built of red and buff sandstone, the minaret has alternating angular and circular flutings with projecting balconies surrounding each of the four stories. Bands of decorative inscriptions define each story with undulating curves. The tower has a diameter of 46 feet at the base and 9 feet at the top.

The mosque, built in 1198 by the Sultans of Delhi, marks the beginning of Indian Islamic architecture. It consists of a rectangular courtyard enclosed by cloisters, erected with the carved columns and architectural units of 27 Hindu and Jain temples, as recorded in the inscription at the main entrance. The complex includes an imposing gateway, a tomb, and another minaret, the Ala’i Minar, to the north of the Qutb Minar. India’s Muslim population of 140 million, comprising 13% of the total, is the world’s third largest after those of Indonesia and Pakistan.

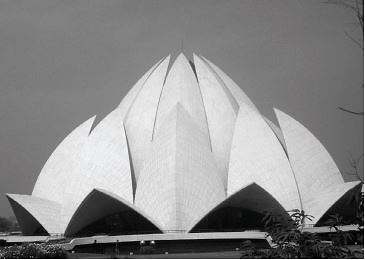

Baha’i Temple

Delhi is known as the City of Seven Cities, as it sits atop seven previous ones. The ruins, which used to be outside the city, are now all within it due to expansion; within these boundaries are 175 National Heritage Sites. All of South Delhi was built following independence; a landmark building here is the lotus-shaped Baha’i Temple with its nine soaring white marble petals. We drove through an upscale neighborhood with million-dollar homes and gated communities with guards, malls, and brand name shops, including a MacDonald’s advertising veggie burgers. Signs for doctor’s offices and real estate agencies dotted the landscape.

At the Kashmir Emporium, we learned about silk rugs over kahwa — green tea with saffron and cardamom — the typical drink of Kashmir. Kashmiri rugs, woven at home, have up to 4000 knots per square inch and use a great deal of green, as opposed to rugs woven by Muslims, who do not use the Islamic sacred color.

As we drove by an electronic billboard showing the nation’s population, it flipped to one billion 119 million, underscoring the country’s major social problem. 52 children are born per minute in India, which has 20 times the population density of the US in one-fifth of the land mass. Having the world’s youngest population — 35% under the age of 14 and another 35% between 15 and 35 — India spends 0.5% of tax revenue on educational infrastructure and has put a school in every village.

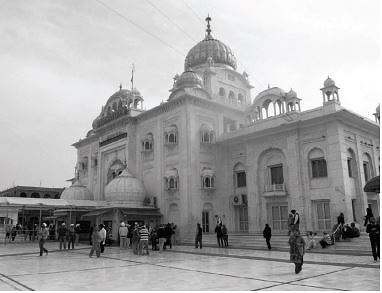

Sikh Temple

A unique experience was visiting the Sikh temple, or gurdwara, of Bangla Shaib. Covering our heads with saffron-colored scarves and in bare feet, we toured the Prayer Hall and the Community Kitchen, meant for providing food to all devotees. We watched large groups of men and women chop vegetables, bake bread, and serve food to hundreds of people. From an open cart outdoors, semolina halvah was distributed to the congregation following prayers, which are required as part of the daily routine.

20 million Sikhs live in the Punjab and Delhi area, and are easily spotted by their wrapped turbans. In the 15th century, Guru Nanak introduced a philosophy combining Islamic elements and Hinduism. He advocated a single god, whose major quality is Sat (Truth) and who reveals himself through his gurus (teachers). Guru Nanak promoted meditation and equality, and opposed ritual, idols, castes, superstition, astrology, and gender discrimination. Nine other gurus consolidated his teachings, and the tenth one formalized the new religion in 1699, beginning a baptism ceremony, which also removed Hindu caste names.

The word Sikh means “student,” one who learns; ten gurus “show the way.” To attain the distinctive Sikh personality of “disciplined outlook,” one must adopt the five kakkars, or symbols, known as the “five K’s”: long unshorn hair, a comb, a sword, a steel bracelet, and a pair of shorts. Tall people in general, with an average height of six feet, Sikhs are distinguished by military prowess and tolerance, protect nature, and are vegetarian. They abstain from all intoxicating substances, such as alcohol and tobacco, and follow the teachings of the gurus from their book of holy scripture, which advocates optimism and hope.

At lunch French-fried sweet potatoes and date pie a la mode joined my list of memorable tastes. In the evening we had dinner at the home of a middle income family with two daughters, one recently married, the second studying for entrance exams for an MBA. After dinner the mother showed us her daughter’s wedding album, saying “This was a small wedding; we only had 400 guests.”

Our journey the next day began with the common greeting of Namaste, literally “Bow to you,” as we left for Jaipur, a city of 4.5 million lying 200 miles southwest of Delhi. Although we were on our way by 7 am to beat the morning traffic, everything with legs or wheels seemed to be on the road. We passed through satellite towns with high glass buildings, which house many of the country’s call centers, surrounded by corporate towers and residential apartments. Many people were leaving to go home. 200 employees — all young college graduates — handle 5-10,000 technical support calls daily here, mostly from the US; therefore, they work through the night to accommodate the time difference. A $500-a-month job in India would cost $3-4,000 in the US. To ease traffic congestion, a new metro is about to open between Delhi and Gurgaon, where the airport and many of the call centers are located.

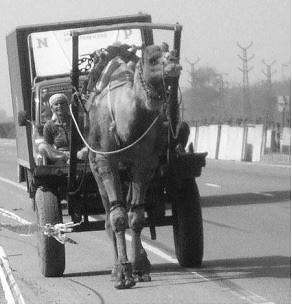

Camel cart

Heavy smog began clearing as the air warmed up. We crawled through a toll gate onto National Highway 8, despite the fifteen lanes on each side; 100,000 vehicles travel daily on this highway. The World Cup cricket tournament was also being held. Introduced by the British, cricket has become India’s national passion and is played everywhere. Players are treated as stars; top players earn as much as $1.5 million a month. 5% of the population is made up of the wealthy, which seem to be divided among politicians, religious leaders, and industrialists. 78% of the people subsist on agriculture and still drive camel carts.

Entering Rajasthan, we stopped to pay state road tax, which is based on the number of seats in each vehicle. Peddlers at the toll gate waited with cobras in baskets to attract people for souvenir shots at $2 each. Fields were covered with yellow mustard flowers surrounded by white boxes for collecting honey. We were on the verdant side of Rajasthan, which becomes desert land beyond the Araballi mountain range dividing the state. The hills are rich in mica and iron ore; nearby the Japanese are building a factory.

Women’s clothing in Rajasthan is distinguished by colorful waist-length headscarves and long skirts or baggy pants. A group of women passed by on camel carts, pulling their scarves down over their faces to indicate that they did not wish to be photographed. “There are more temples in India than hospitals,” commented Rajesh, as a new Hindu temple emerged by the road. A line of cows sat on the road divider, leading to another comment that Rajasthan was India’s milk center, exporting condensed milk to other states for use in the confectionary industry.

Driving by bougainvilleas, ashoka trees (named after a king) providing shade along the roadside, and fields of elephant and pampa grass, we reached Chomu. Upon arrival at the Chomu Palace Hotel for lunch, we received the customary tilak mark between the eyebrows. The three-story hotel, formerly a rajah’s palace, was impressive with its pillared balconies, arched and recessed arcades, and niches framing stone sculptures and white marble urns on the outside. Decor for the various courtyards included ornamental pools, a fountain protected by the plumage of a stone peacock, niches inlaid with semiprecious stones, a variety of wall masks, and marble flower pots resting on the backs of stone elephants. The opulent dining hall, surrounded by second-story balconies, had stained glass windows, mirrors, marble fireplaces, ceiling friezes, miniature paintings, and portraits, including several of the rajah. Highlights of our lunch were a clear soup flavored with coriander and lemon, and moist, delicate gulab jamun served warm — the best we had had so far.

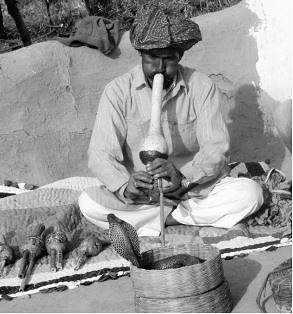

Snake handler

Close to Jaipur we stopped at the Snake Handlers’ Village, where we observed local lore in the midst of poverty. Dark-eyed, barefoot children ran to meet us, and then lined up against a wall to watch a young girl dance, hoping to receive money in return. She emulated the curved movements of a snake, while a man played the flute to charm a cobra out of its basket. Meanwhile, some women baked bread over open fires in front of their shacks, and others carried jugs of water from the pump on their head. Skinny goats scampered about, finding grass in a torn bag, while a baby cow suckled at her mother’s teat.

Rajasthan puppets

Rajasthan is awash with palaces. Ten kilometers from Jaipur is the Amber Fort, which stretches nine city blocks and has seven gates. This 16th-century structure is built on four floors and houses several palaces within its walls. This was my second ascent to the Fort, the first having been on an elephant in 2002. Due to the increased number of tourists, the wait for an “elephant taxi” is now too long. I also missed all the monkeys that used to scurry about on all four levels. Vendors have replaced the monkeys in the square roundabouts. Rajasthan puppets in their distinctive clothing vie for the attention of tourists along with palace guards in traditional uniform, who have no other function in today’s democratic India.

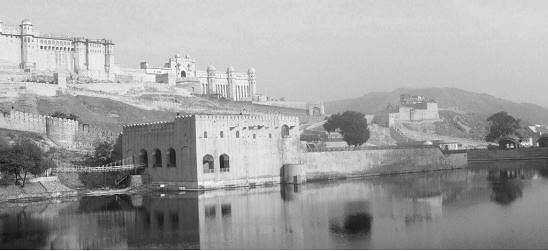

Amber Fort

The Ganesh Gate provides access to the private inner areas of the palace, which are covered with frescoes and mirrored ceilings. Of special note is a mirror-embossed room called the Sheesh Mahal. Ganesh, believed to remove obstructions in people’s daily lives, is the god of good luck. His likeness is painted or placed over the main entry into a building. Over the Ganesh Gate is a chamber with lattice screens for royal ladies to view state functions below.

After spending a couple of hours amid opulence, we descended to visit Jaipur, known as the “Pink City.” In 1826 the maharajah had the city painted pink in honor of a visit by the King of England. All houses in the old city are required to be painted some shade of pink. Rosy sandstone buildings take on a warm glow in sunlight. Another unique feature of this city is the way vegetables are bought in the market; the minimum purchase amount is five kilos, which is then delivered to one’s home. Likewise, large containers of raw milk, which must be boiled at home, are delivered to one’s doorstep. The milk delivery reminded me of my childhood in Turkey, where similar jugs used to arrive on horseback.

A visit to a jewelry shop introduced us to various gemstones, Jaipur’s biggest industry. Garnet, topaz, amethyst, and black star are mined in India. 10-15% of Jaipur’s population is engaged in the workmanship of gems, even ones mined outside the country, like diamonds. India is the largest global consumer of gold, which is purchased as an investment. Jewelry is always inherited by women, never by men. My purchase here was a garnet ring.

The City Palace (formerly the Royal Palace) has intricately carved and painted arches and balconies typical of Mughal architecture. A colored glass peacock, which appears on many postcards, is exquisite. A different peacock motif appears above a gate flanked by guards in traditional attire; they pose for hundreds of tourists, who jostle to photograph them. The palace has collections of fabrics, decorated weapons, paintings, and carpets. Its Textile Museum displays lavish costumes of the royal family, weighed down with gold thread or jewels; this appears to be a source of inspiration to Indian women, who love to adorn themselves.

Rajesh treated us to cocktails on the bus as we rode to a home-hosted meal in the evening. We had Indian rum and Coke, accompanied by spicy peanuts and thin potato sticks. The dinner was a window onto the lifestyle of a family from a wealthy background. As soon as we entered, our attention was grabbed by wall-mounted heads of animals — leopards and deer with antlers — killed by our host’s grandfather during his hunting expeditions. The two-story, four-bedroom house had family antiques throughout, such as a clock, swords, and daggers, which belonged to the Rajput family our hostess had married into, arriving from Jaipur as a bride. The house also had two shrines — one indoors and one outdoors.

The husband worked for the government and painted in his spare time. His wife ran an orphanage next door for twenty HIV-positive children — fifteen boys and five girls. We met the girls, who ranged in age from five to thirteen; they lived in the main house with their adoptive parents. They watched TV upstairs while we had dinner, which included rice, chicken, cauliflower, eggplant, lentils, and potatoes, accompanied by cucumber and tomato salad. For dessert we had fresh fruit in cream. Afterwards we toured the house; in the master bedroom, a glass case of bangles, arranged by color to go with the wife’s different outfits, did not go unnoticed. All in all it was a delightful evening.

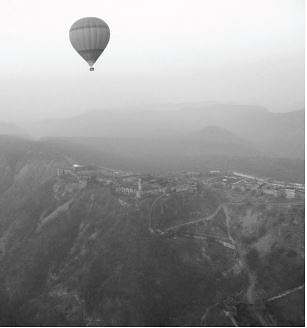

Floating over

the Amber Fort

In the morning I was picked up at the hotel at 6 am for an optional balloon ride over Jaipur and surroundings. Ever since my first such ride over the Nile in 2004, I have greatly enjoyed hot-air balloons — a passion attested to by the image on the cover of this book. We took off as the sun slowly rose in the sky; floated over Amber Fort, following its undulating walls up the mountain; saw antelope, water buffalo, and monkeys below; and spotted peacocks, which flew away as we approached. Because there was little wind, we landed in a different spot than where we had started. Seeing us land, a few village boys ran over to help pull the balloon near the road; other children arrived, some with their mothers. By the time we descended we had the entire village around the balloon, smiling and waving to us.

Due to our delayed landing, Rajesh had brought a boxed breakfast for the two of us who had been on the balloon ride to enjoy on the way to our next excursion, the Jantar Mantar (Instrument and Formula) Observatory — an intriguing set of outsize astronomical instruments designed by Jai Singh in the 18th century, mostly to calculate time more precisely. A local astrologist and guide gave us a tour of the various sundials, demonstrating how watching the sun’s shadow helps tell time. He also offered to look up our astrological charts based on the time, date, and year of our birth. I did not partake in this opportunity.

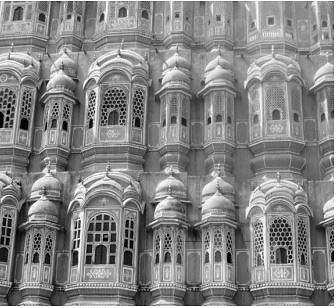

Honeycombed windows

of Hawa Mahal

The Hawa Mahal (Palace of the Winds), built in 1799, is Jaipur’s landmark; this sandstone building with honeycombed windows served as a grandstand for palace women. In front is a colorful market, the Badi Chopar, where just about everything is sold — from bangles and puppets to attar (a perfume) and henna tattoos. Here I bought a child-size version of a multicolored processional parasol, which ended up as a lampshade in my summer cottage. I also bought a pair of marionettes clad in deep blue Rajasthan costumes.

Carpet weaver

Rug weaving and textiles are among Jaipur’s top crafts. We visited a block printing workshop, where men used carved wood blocks dipped in natural dies to print on cotton cloth. To apply multiple colors to a design in repeated patterns, four points on a wood block are aligned with four points on the cloth.

Wool carpets are knotted at the loom by men and women. Goat chin hair is used over a cotton base. After knotting is finished, a carpet is trimmed from the back side with special scissors before being washed and hung to dry. Camel hair is used for all-wool carpets.

The next day our journey continued to Ranthambore National Park, 80 miles south of Jaipur. We drove through the countryside into the low Vindhya Mountains. On the road were trucks overloaded with cattle feed. To keep evil forces away from these top-heavy trucks, which overturn easily, each one is adorned with seven chili peppers and a lemon or an old shoe. The co-driver uses hand signals to slow down vehicles coming from behind or to indicate they can pass, while the driver concentrates on the road ahead. We passed wheat and lentil fields, nourished by ground water from wells. Farmers dig up areas to collect rainwater; the agricultural economy depends on rainfall.

Cleaning dishes with clay

A stop in a village by the roadside was an insight into the hard life of women; women pumped water and cleaned dishes with clay, while men sat around and inhaled tobacco from a long pipe as it burned in a small clay pot. We were surrounded by school children in uniform and teenage girls with head covers, all eager to be photographed. Goats and cows were chained near a trash heap so that they could feed on it. Everyone waved goodbye to us with big smiles, once again illustrating the hope and optimism Hinduism delivers for the next life, despite the hardships of the present one.

Two other stops before our final destination were equally rewarding. A cafe where we stopped to rest was charming, with its colorful round table covers, all embroidered in chain stitching. My inquiry led to a gift shop next door, where such covers were stocked on a shelf. Happily, I walked away with yet another item which I did not need, but which was a great addition to my craft collection.

An impromptu stop at a guava orchard familiarized us with this tropical fruit, which looks like a large pear, but turns yellow when ripe. Obtaining permission from the owners, we walked through the orchard to spot ripe guavas to taste; they were sweet and juicy. Women in colorful garb and ankle bracelets worked the orchard, collecting the fruit in large sacks hanging down their backs and preparing it to be taken to market. We bade goodbye as cheerfully as everyone had welcomed us.

Finally, we arrived in time for lunch at the Nahargarh Hotel on Ranthambore Road near the National Park. Although only five years old, the hotel looked like a palace, with buildings facing a beautiful interior courtyard. A film shoot was underway when we arrived. My room looked very elegant; I looked forward to sleeping in the canopy bed.

Ranthambore National Park is a rambling 154-square-mile forest in southeast Rajasthan, established in 1973 as a tiger sanctuary and now home to 35 tigers. Hunting was outlawed in 1970. In the middle of the park is the Ranthambore Fort, a massive fortification with seven gateways, built on a rocky outcrop during the Chahamana Kingdom in the 5th century. An open four-wheel-drive vehicle, known locally as a “canter,” is the mode of transportation within the reserve.

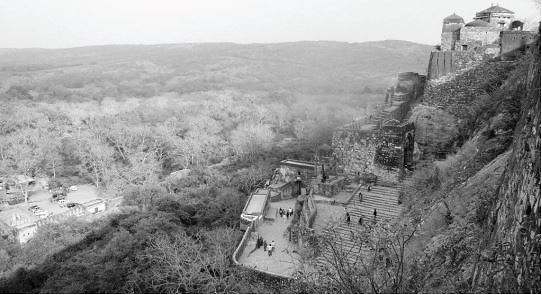

Ranthambore Fort

Hanuman langurs

When we arrived at the park, we were met by hanuman langur monkeys at the gate. Named after the Hindu monkey-god Hanuman, these langurs are sacred in India and go around in groups. Like other primates, they groom to form social bonds and often extend the courtesy to other species. During our 238-step climb to the top of the mountain, monkeys sitting or grooming along the fortress walls were a delightful scene. As we gained height, we were able to enjoy the view of the surrounding hills and, with the aid of binoculars, spotted crocodiles sunning themselves on the shores of the river below.

Throughout the fort’s history, various buildings have been constructed within its walls by conquering kings and sultans. There are several fine mausoleums here, as well as a temple to Ganesh. Near the temple are small stone constructions depicting people’s wishes to have a house, as well as ribbons tied to trees so that wishes would come true. After visiting the temple, people feed corn to the cows and monkeys. Both species seemed to enjoy the communal feast on the ground.

Following dinner at the hotel’s outdoor restaurant, we had a lecture and slide show by a naturalist about the park and its wildlife — tigers, leopards, antelope, deer, monkeys, owls, and many birds. I went to bed with great anticipation of our early morning game viewing.

At 6:30 am, our “canter” began wending its way through the rough roads of the reserve, following fresh tiger footprints. Instead of a tiger, we located a variety of deer — spotted, sambar, antelope, and male deer with beautiful antlers — as well as wild buffalo and peacocks. A giant crocodile, resembling a log, was stretched out on the banks of a red algae-filled river. A variety of birds — including egrets, hornbills, and nightingales — enriched the forest tapestry. Somewhat disappointed not to have seen a tiger, we returned to the hotel for lunch.

Tiger going home

A second safari in the afternoon took us to another zone in the park. Here we saw an egret riding on the back of a buck. Our naturalist guide seemed to know each of the park’s 35 tigers, as they have distinctive facial stripes. He spotted one tiger far away under the trees and, anticipating where it would go next, asked the driver to follow his instructions. By now other guides had spotted the same tiger, so we had a dozen vehicles racing on tight roads and trying to overtake each other. Finally, we caught up with the tiger, which was stalking a deer, which was enjoying an algae meal at the edge of the lake. While I was glad to be this close to the tiger, I was not keen to see it dismember a deer before my eyes. Fortunately, the deer got wind of the tiger and ran away. Disappointed, the tiger turned toward us in full view; then, apparently not interested in human flesh, he turned his back and walked away. We were all relieved and pleased at this close encounter.

A morning stroll to observe a day in the life of a rural community was insightful. Here again women performed physical labor, while men handled business in shops. This traditional division of labor is also a function of women’s literacy level, which is much lower than that of men. Dressed in vibrant colors, women cheerfully carried on their heads water jugs or bowls of dung, which they then mixed with hay and water. Kneading this mixture by hand, they formed large patties, which are used in housing construction or as fuel. Other women washed dishes with ashes from a fire, while their children, somewhat shy, gathered around us with curious eyes.

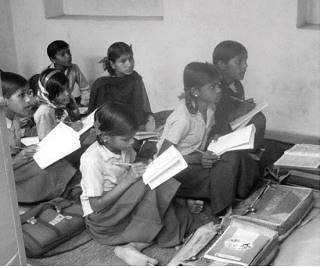

Fifth-grade classroom

Walking over to the Saini Adarsh Vidhya Mandir village school, we met the founder. Having come from a lower caste, this man was very proud to have been able to start a school, which had 95 students in kindergarten through fifth grade. He hoped to add more grades as he located teachers, one per class. I was invited by a fifth-grader to visit his class, so I went in. The teacher asked a few students to count to 50 in English, then showed me their math book, which introduced numbers by pictures in units of two, three, four, etc. The students also read out loud in unison; since other classes were reading at the same time with open doors, all the sound reverberated in the courtyard. As we departed, we left a few gifts which had been suggested to us, such as a soccer ball and a jump rope.

Our village tour continued with a visit to a home with five children — three boys and two girls. We were treated to chai (tea), made by boiling a pot of water over a fire and adding tea and spices. The house consisted of a large room with a shrine and had a bedroom in one corner. The kitchen had open cabinets for utilitarian items and on the wall three hand-crafted pieces that caught my attention — long bands of embroidered or sequined cloth, each a different color, with a fringe at one end and a stuffed cloth ring at the other. These wall hangings turned out to be headpieces which women wore when carrying jugs, placing the stuffed side on the head to keep the jug steady. I was so taken with these beautiful utilitarian items that I instinctively asked if I could buy one. After selecting one I liked, I waited for the mother to confer with her daughters to determine the price — I happily paid $7.

A short distance away was the Women’s Cooperative, founded to provide employment for village women and support their crafts. As we approached the building, rows of fabric with tiger block-prints hung on clothes lines. Sitting on the ground in the shade of a tree, a group of women worked together on a quilt; others embroidered, while keeping an eye on toddlers nearby; one woman used her toes to loop yarn, while she braided it into sashes. Inside, a roomful of women kept busy at sewing machines, making cushion covers, tablecloths, napkins, shirts, and jackets from hand-printed fabric. The shop was jammed full of handicrafts at very reasonable prices. I bought a reversible batik jacket for the equivalent of $22. We had lunch in the dining room of the Cooperative. I was lucky to have a table companion with henna-adorned palms, who allowed me to photograph her hands.

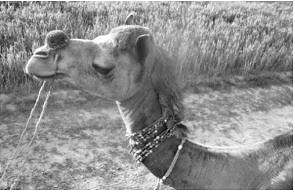

My decorated camel

The Aagman India Camp on the outskirts of Abhaneri is an Overseas Adventure Travel village retreat. We were welcomed to the beat of a large drum, while camp staff adorned us with flower garlands. We quickly settled into our individual tents with electricity. Donning large, colorful headscarves — courtesy of Rajesh — to fit in with the locals, we mounted decorated camels for a trek to a nearby village. As we traveled on narrow rural roads flanked by mustard fields, bird sounds were our only accompaniment. Barefoot village children waved as we passed by their homes.

Back at camp, as soon as our camels were relieved of their saddles, they lay down and went into a scratching frenzy, rubbing their backs on the ground. Seeing a group of camels with their feet in the air, all scratching, was both funny and memorable.

In preparation for dinner, Rajesh offered a cooking class, making two kinds of bread — chapatti and dosa — as well as a cauliflower and potato dish with chili peppers, ginger, and pureed tomatoes. A delicious flavor for the latter develops by cooking the spices until they separate from the oil, before adding them to the dish. Dinner was followed by merriment, with dancing and drumming around a campfire.

The next day started with a cricket lesson, followed by practice in walking with a water jug on our heads. With two camp staffers on either side of me to catch the jug in case I dropped it, I finally managed to balance an empty one, appreciating this skill, which village children learn at a young age. Riding a diesel-powered cart to the town of Sikandra completed our rural experience.

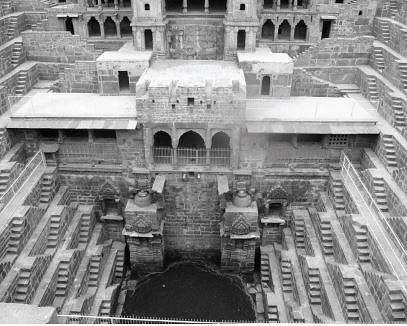

Step well

On the way to Agra in Abhaneri, we became acquainted with a baoli — a step well complex. The Chand Baoli is one of India’s oldest step wells, built by King Chanda of the Nikumbha Dynasty in the 8th and 9th century. At a depth of 19.5 meters, the well is reached by flights of steps on three sides of a square area, with a multistory corridor on pillars and two projecting balconies on the fourth side. The repetitive pattern of the stone steps creates an impressive visual effect. Enclosed by a wall with side verandas, which have elaborate carved reliefs in niches, the Chand Baoli is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Traveling on alternating bumpy and paved roads through the vast rural countryside, we reached Agra in Uttar Pradesh, one of India’s most populated states, with 140 million people. The streets looked more crowded and dirtier than during my visit in 2002. We passed a temple procession, a motorcycle with five passengers, a bicycle pulling an overloaded cart, a cow rummaging through trash, and a man obliviously sleeping on the sidewalk. Before we called it a day, Rajesh proposed a view of the Taj Mahal from the banks of the River Yamuna, as well as a visit to the Tomb of the I’timad-ud-Daulah (Lord Treasurer), referred to as the Baby Taj and situated on the east bank of the river.

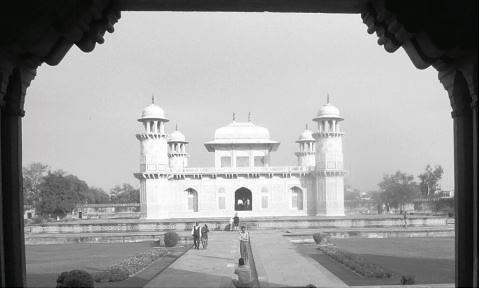

Tomb of I’timad-ud-Daulah

Built from 1622 to 1628 by Nur Jahan for her parents, the Tomb of the I’timad-ud-Daulah is considered a masterpiece of Mughal architecture, and was the first building made of white marble, marking the transition from sandstone to marble construction. Mughal architecture is characterized by its symmetry, gardens, and stone inlays. Approached through ornamental red sandstone gateways with inlaid marble designs, the tomb is in the center of the Char-Bagh (Four-Quartered Garden), surrounded by walls and side buildings. The garden is divided into four equal quarters by water channels in raised stone pathways. The tomb has octagonal towers and facades with three arches, the central one an entrance to the interior square hall housing the cenotaphs of the Lord Treasurer and his wife; tombs of family members are in the adjacent halls. The exterior has stylized floral arabesque and geometric designs in jewel-like stone inlay. This visit, coupled with the pinkish glow of the Taj Mahal across the river, whetted my appetite for the next morning’s tour, which Rajesh said would take three hours, with him as our guide; he had a degree in architecture. Then we were off for a thaly dinner.

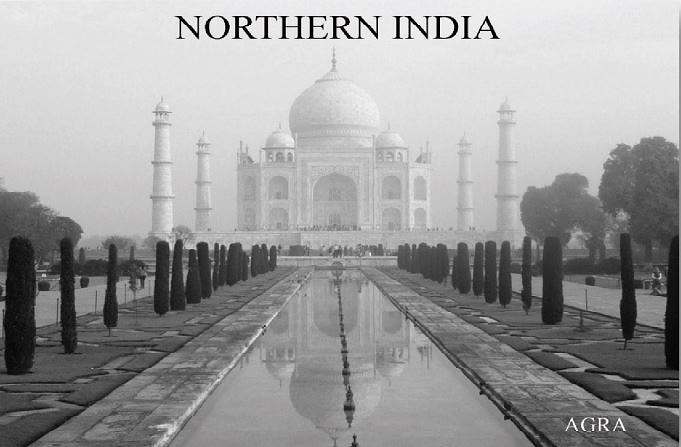

The Taj Mahal (Crown Palace)* is the Mausoleum of Mumtaz Mahal (the Chosen One of the Palace), wife of Shah Jahan, whose death in June 1631 was considered holy, as she had just given birth to her fourteenth child. Mumtaz had been the emperor’s wife, companion, and adviser for seventeen years. Channeling his despair into the creation of a mausoleum, Shah Jahan consulted top architects and craftsmen and chose a Persian master builder to honor the memory of his wife. It took 20,000 artisans to build the complex over a period of 22 years.

* See postcard image at beginning of article.

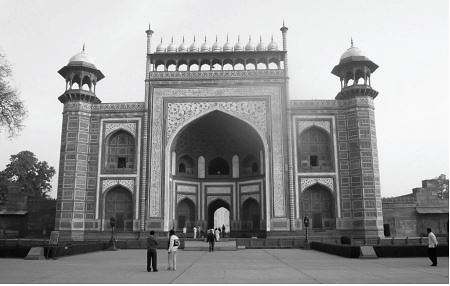

Gateway to Taj Mahal

A red sandstone gateway, inlaid in white marble and graced with a calligraphic quotation from the Koran, leads into the Taj complex, which is contained within a walled garden. The centrally situated marble mausoleum, built on a platform, is at the edge of the river so as to benefit from the light and is silhouetted against the sky, while reflecting in the long fountain pool in front. Minarets, two on each side, provide a decorative touch. All the architectural elements are in perfect balance, including two onion domes built one within the other for support. A guest house on the right completes the symmetry of the mosque on the left. Four gardens, one in each corner, are divided symmetrically by water channels.

On the platform, verses from the Koran, panels of low-relief carving, and inlaid designs in precious and semiprecious stones from around the world cover the exterior. Inside, cenotaphs for Mumtaz and Shah Jahan lie surrounded by a trellis screen. We spent the morning wandering through the gardens, viewing the white marble of the Taj from different angles. As the hours advanced, the soft morning light gave way to the hard light of midday. Visitors speaking many tongues poured through the gate; the tranquil gardens were no more, signaling it was time to leave.

Pietra dura

A visit to a pietra dura (hard stone) workshop was a good opportunity to see the difficult, precise skill of patterned stone inlay being practiced. A master craftsman draws a design on a slab of marble, which comes from Makrana, near Jaipur. Imported stones — turquoise, carnelian, lapis lazuli, jasper, jade, and agate — are selected, cut, and chiseled. After beds for each pattern are gouged, each design is fitted, finely adjusted, and glued; then the surface is polished with fine emery. A light source under a finished piece makes the jewels glow. This is a craft handed down through generations of families, many of whom have workshops in the back lanes of Agra. The pieces range in size from small objects to large dining tables. I bought a picture frame to add to two other objects I had from my previous trip.

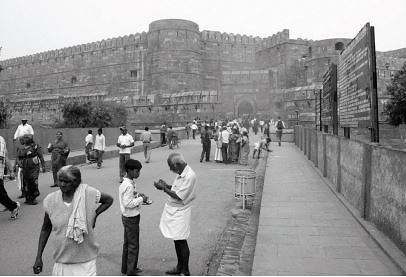

Agra Fort

In a city of architectural jewels, the Agra Fort is an impressive landmark. Built by Akbar on the site of another castle from 1565 to 1575 to withstand long sieges, the sprawling fort on the banks of the River Yamuna contains two palaces, private and public audience halls, a mosque, and other rooms around a central courtyard with square arches and broad decorative brackets. Shah Jahan, Akbar’s grandson, added exquisite inlaid white marble spaces to the double-walled fort, which is built of the same red sandstone that distinguishes many great Mughal buildings. These marble additions, displaying a refined elegance, are in striking contrast to Akbar’s rooms with their densely carved decorations giving them the look of Hindu buildings. The sweeping view of the city below includes the Taj Mahal, which added to Shah Jahan’s sadness when he was deposed by his third son, Aurangzeb, in 1658 and kept prisoner here until his death in 1666.

To reach the temple city of Khajuraho, we took the train from Agra to Jhansi, a major junction on the crossroads to South India. The Agra train station bustled with passengers, whose mode of transporting luggage was striking. The platforms were full of women with big bundles, men with stacked suitcases, and others with a combination of suitcase and bundle, all carried on the head. While stylish women in saris pulled trendy luggage on wheels, men in dhotis pulled carts loaded with tin cans. People on bicycles with luggage tied on racks wended their way around families on blankets, their children sleeping or playing nearby. Meanwhile, we waited at a different area of the platform than that marked for our destination, as instructed by Rajesh, because trains often do not stop where indicated. We felt fortunate to have guidance from Rajesh, who told us that the Indian word for “travel” means “suffering.”

The Delhi-Bhopal fast train pulled up on time; we had a pleasant 2½-hour ride through the wooded landscape south of Agra to Jhansi, where we descended at India’s second largest railway platform. Initially established by the British, India’s railway system is good, with 2.5 million employees. Jhansi is the center of Bundela civilization. It is a city of 1.5 million people, and is famed for its legendary warrior queen Rani, who rose up against the British with the help of her bodyguard, until her husband, Raja of Jhansi, sided with the British in the Mutiny of 1858. Queen Rani rode into battle dressed as a man and with her baby strapped to her back, and was killed.

Continuing overland on a bumpy road, we headed to Alipura for lunch, stopping on the way to see a farm which used a simple irrigation system to grow crops. By constantly walking around a well, a bullock operated a water wheel, filling its pails and dumping the water into a channel leading to the field. At the farm we tasted fresh garbanzos and walked through organic tomato, carrot, onion, and anise fields.

After traveling another two hours eastward from Jhansi in the state of Madhya Pradesh, we finally arrived toward evening in Khajuraho, named after the khajur tree (date palm), which grew here in ancient times. After a long day, I felt ready for an ayurvedic massage. Through the hotel I was able to make an appointment at the nearby Ayurvedic Health Center, which also took care of the round-trip cab fare. In ayurvedic massage, different oils are used for the different parts of the body, starting with the scalp and followed by the torso and limbs. A few minutes in a steam machine and a body scrub in a shower with granular herbal soap complete the treatment. I was given a special shampoo to work into my oily hair, which my masseuse then helped to blow-dry. Further relaxing over a cup of herbal tea flavored with cardamom, saffron, and ginger, I returned to the hotel.

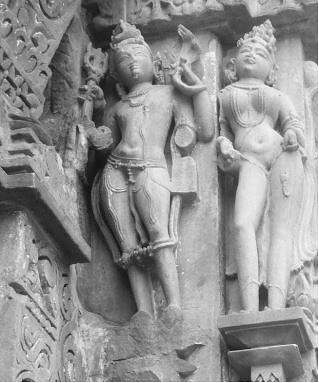

Temple sculpture at Khajuraho

Forested isolation protected Khajuraho’s cluster of temples from Muslim destruction. Thus, they are the only remaining examples of Central Indian temple architecture, characterized by a high platform without any enclosure wall and interconnected components built on an axis. Created from 950 to 1150 by the rulers of the Chandella dynasty, a Rajput clan who resisted Muslim invasion, the temples were subsequently lost in the dense jungle until 1819. It is believed that Khajuraho, discovered by the British, was once known as the City of Shiva; sculptures decorating the temples recount and celebrate the marriage of Shiva to Parvati. Erotic carvings on the exterior of the temple walls portray the consummation of marriage and, at the same time, the highest spiritual experience achievable according to Hindu philosophy. Love-making is considered to demand giving all one’s senses in order to achieve total physical and mental union. The portrayals of copulating couples are auspicious.

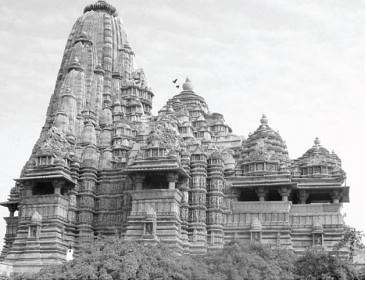

Kandariya Mahadeva temple

The Chandella dynasty ruled over central India for 500 years. They built 24 temple complexes, three of which are constructed wholly or partially in granite, the rest in sandstone, transported from the Ken River, 20 miles away. The soft river stone was then cut and carved before it hardened. The temples, divided into four groups — Western, Eastern, Southern, and Jain — are dedicated to Shiva, Vishnu, and Jain pantheons. Despite these diverse affiliations, the temples are similar in architectural style. They are considered one of the seven wonders of India and have been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Of the dozen-or-so temples we visited, Kandariya Mahadeva stood out with its sikhara, or tapered temple tower, clustered with 84 smaller towers in ascending order of height.

The Western Group of sculptures has spectacular carvings of processions, domestic scenes, musicians, and dancers. Although once considered an affront to post-Victorian sensibilities, these erotic images of amorous couples, sensuous nymphs, and idealized women have become widely admired for their beauty and attract many visitors. As I watched devout women in head covers and long skirts climbing the steps of a temple for puja, I could not help but wonder at how times have changed for Hindu women, who no longer reveal their bodies even in a bathing suit, dipping instead into sacred rivers in their saris.

The temples are surrounded by an extensive makeshift market for puja items, where each vendor stakes out an area by placing a piece of cloth on the sidewalk. Gazing at heaps of coconuts, dye cones, tinsel ornaments, bangles, and a variety of food, we walked to the Jain Group of temples, where we visited Parsvanatha, Khajuraho’s largest Jain temple, with a plain facade leading the eye to multiple sikharas. The carved images inside the temple are mostly of Mahavira (the Great Hero), founder of Jainism, who lived as a naked ascetic until he reached spiritual knowledge. Jains believe that the universe is infinite, not created, and that souls are present in every living creature; hence they revere all life and are strict vegetarians. The practice of a strict code of behavior is believed to lead to moksha — reincarnation and salvation.

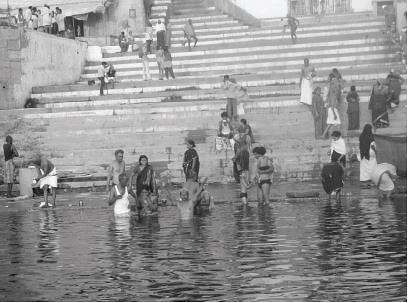

Pilgrims bathing

in the Ganges

Our fascinating trip to Khajuraho was followed by another one, as we flew to Varanasi, in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Varanasi, also known as Benares, is the spiritual center of India. This 3500-year-old holy city is a major pilgrimage site and the location of the most revered banks of the River Ganges, which flows down the slopes of the Himalayas. Visiting Varanasi once in a lifetime is the goal of every Hindu; dying here means the greatest chance for moksha. 50,000 pilgrims a day descend on Varanasi, which Hindus simply call Kashi (the City of Divine Light).

Our tour began at the market, where we each chose a color for custom-made bangles, which a shopkeeper then assembled into a set of a dozen, varying in width and ornamentation. Not knowing what to expect, I was delighted to receive my box of green bangles, which were delivered to the hotel. The attractive set includes a few thin silver bangles, and may be worn in any number of ways.

In the evening a tuk-tuk ride down continuous bazaars and through crowded filthy streets to the banks of the river was a surreal experience, which unraveled before me like a Fellini film. Blonde Caucasian mannequins clad in saris stood on pedestals, sharing the sidewalk with a barefoot homeless woman wrapped in a blanket with her belongings in a bundle on her head, a man repairing leather bags at his sewing machine, a woman shelling peas for sale on the pavement, a man pumping water, and countless beggars with tin cups in outstretched hands. Meanwhile, cars, cows, bicycles, and tuk-tuks jostled for space on the street.

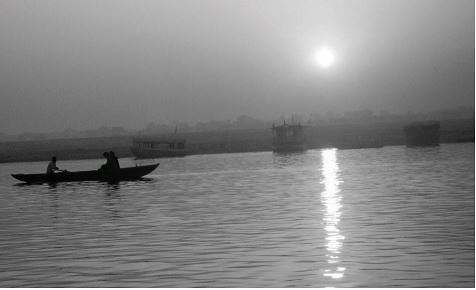

The river banks overflowed with people as if they were waiting for fireworks to begin, but the gathering was for the Ganga Arati, the daily Hindu evening worship of the river. For a good view of the ritual service, we went out on the river in hired boats. As we got on board, we each purchased a tiny oil lamp made of leaves to add to the hundreds floating on the sacred water. Instructed to think of a loved one who had passed away, we each dropped our oil lamp gently onto the shimmering surface of the Ganges. Our small boat — rowed in synchrony by two young men, one at each oar — moved slowly, taking us to the middle of the river. The ghats (broad steps leading down to the water) were ablaze with lights, whose reflections also blanketed the river’s edge. Conducted by priests, ritual sounds, along with the floating lights on the sacred waters, left boatloads of visitors spellbound.

Early in the morning we went down to the river again to see the sunrise and Hindu morning rituals. We went part of the way by tuk-tuk, then walked through the bazaar, which was not as crowded as the night before. Men and women sold different-length bundles of a particular type of tree branch, which people chew to split into fiber and use as a toothbrush. We stopped by a money changer’s stand, where we traded paper rupees for coins to give alms to the poor; the streets and ghats were lined with beggars. Most of them lepers, poor people, including many children, sat with tin pans in front of them. We dropped a coin in every beggar’s pan for good karma. They take these coins back to the money changer, who exchange them for paper rupees. Thus, the coins are constantly recycled; the money changer takes a commission with each transaction, even from the poor.

Holy follower of Vishnu

Before the morning cruise, I walked along a few of the ghats to get a close view of the rituals. Varanasi was indeed a nonstop pilgrimage city. Hindu pilgrims arrived in large numbers to receive darshan (a meritorious glimpse of a god). Some pilgrims meditated; others bathed in the sacred waters along with their children to cleanse their sins. Girls sold flowers out of bamboo baskets as tributes to the Ganges. Holy men who follow Shiva or Vishnu, indicated by horizontal or vertical markings on their foreheads, performed puja.

As dawn crept in, we began a leisurely boat ride upstream. The sounds of the shehna — a reed instrument played by musicians of the Shiva Temple — set a wonderful mood to welcome the day. The morning haze lifted, signaling to the city that it was time to awake. Vendors opened up their stalls, as a steady stream of pilgrims flowed down to the holy waters to bathe or to do their puja to the new day. Locals engaged in daily activities, such as washing and spreading laundry to dry on the ghats below the high walls of the maharajas’ old riverside palaces.

Our boat turned around to go downstream, along with another boat crammed with souvenirs and following us with incessant pleas from the vendor-captain to buy something. I made him happy with the purchase of small carved soapstone Ganesh. We passed by the city’s two cremation ghats; one had a big pyre of branches ready to burn and the other one was already smoking. Out of respect for the cremation ritual, boats are not allowed to approach burning ghats; no photography is allowed. The city has around 80 ghats, each with its own name, its own Shiva lingam stone, and its own significance, such as Hanuman Ghat for those who worship the monkey-god.

To control traffic congestion in the old city, there are hours of operation for each type of vehicle — trucks between midnight and 6 am and buses till 9 am. Tuk-tuks are not allowed beyond a certain point within the city. On the way back to the hotel, I saw a traffic policeman accept a coin from our tuk-tuk driver; this small bribe sufficed to see us all the way back to the hotel. Having heard about the pervasive corruption in India from the government on down, I did not need to see it to believe it; but I did.

Varanasi is famed for its silk, originally woven to clothe temple deities. White silk, imported from China as thread, is dyed and woven in India. Varanasi brocade, developed by local weavers, is an extravagant cloth that includes silver and gold threads, the latter obtained by dipping silver thread in gold liquid. Fortunately, our hotel was next door to a silk workshop, where we watched two men work a loom in synchrony, using a very old technique predating the French Jacquard cards with holes. Since I was at the end of my trip and my luggage was already bulging, I restricted my purchase to a small brocade wall hanging and a scarf, not indulging in any of the bigger shimmering pieces.

Stupa at Sarnath

Varanasi is a sacred place to Buddhists as well, as the Buddha came to the town of Sarnath, 6.4 kilometers north of the city, to deliver his first sermon. We were fortunate to be this close to the main Buddhist pilgrimage center and glad that it was included in our itinerary. India has just 8 million Buddhists. At the age of 30, the Buddha renounced his privileged life as a prince and left home. Five years later he attained Enlightenment after meditating under a bodhi tree. Offering insight rather than divine revelation, the Buddha began his lifelong missionary work with a sermon called “Setting in Motion the Wheel of Righteousness” and delivered in Sarnath. This was the base from which the religion developed, as well as the site where the Buddha founded his monastic order.

The sacred relics of the Sakyamuni Buddha are located in Sarnath’s Deer Park. The park houses the main shrine (5th century BC) and the Dharmarajika Stupa (3rd century BC). The shrine has wall paintings of the different stages of the Buddha’s life, made by a Japanese artist from 1932 to 1936. On the day we visited, many pilgrims from other countries were circumambulating the stupa. A public exposition and annual procession of the sacred relics around Sarnath takes place on Kartik Purnima, the day of the full moon in November.

My Indian look

On our final evening Rajesh arranged rental saris for the nine women in our group. A local woman came to one of our hotel rooms to dress us. Wrapped in silk saris of various vibrant colors, we all looked glamorous at the farewell dinner. On our final morning we had a yoga class based on the principles of body, breathing, and mind. We did basic stretching and breathing exercises to relax the body and to open up the “third eye.”

All but two in our group of fifteen left for a post-trip to Nepal in the afternoon. I was one of two people who flew to Delhi to begin the flight back home. While I looked forward to returning home after six weeks on the road, I did not regret my decision to undertake such a long trip in a country that takes time to understand — where it takes time to peel away the veil of squalor, chaos, and trash, and to see the spiritual and physical beauty of the land and its people. I returned home with 2000 photos and indelible memories.

Sunrise over the Ganges

← Bhutan