February 2008

A minibus took us to Kasane airport for our flight to Namibia. We flew to the Kwando Airstrip in a twelve-seater aircraft, then walked for about ten minutes through sand to reach a boat, which delivered us to border control and then to our lodge.

The boat ride on the Kwando River (the Chobe becomes the Kwando in Namibia) was one of the most enjoyable parts of the entire trip. With Namibia to the right and Botswana to the left, our pontoon boat moved slowly, creating small ripples over the calm waters. Reflections of trees and clouds shimmered on the river surface, as the boat went in and out of lagoons teeming with birds. An avian spectacle included kingfishers in front of their mud holes, weaver birds in nests that looked like thatched roofs perched on trees, bee-eaters, yellow and red hornbills, African jacana, and many more in a feeding frenzy along the river banks.

Our boat docked in Mudumu National Park at the Lianshulu Lodge, which was our home for the next three nights overlooking the Lianshulu Lagoon. Lianshulu is a word in the local Lozi language meaning “place of spring hares.” Over a welcoming drink the manager, an Afrikaner born in Namibia, reviewed rules, emphasizing the use of mosquito repellent at all times. It was the rainy season and the mosquitoes were out. As I listened, my eyes wandered over the beautiful local crafts that were displayed in the lodge — baskets, wood carvings, and bark paintings. Lunch was waiting — spinach quiche, chicken drumsticks, mixed green salad with balsamic dressing, and homemade bread.

The Lianshulu Lodge and cabins are set in the woods. Due to heavy rains, a tented camp in the wilderness where we were originally going to stay was closed. Needless to say, we were pleased with the upgrade. Not only were our cabins spacious and comfortable, but they each had picture windows and a sliding door that opened onto a deck surrounded by trees. The twin beds were canopied with giant mosquito nets.

Hippo coming up for air

Following our afternoon quiet time, we had tea and then took off in a pontoon boat for a sunset river cruise. The vegetation along the river provides material for practical goods. Common reeds are used for making fences, bulrush for baskets, and papyrus for floor mats and baskets. Three types of water lilies grow in the river — white day lilies, yellow night lilies, and blue night lilies, a cross-breed of the other two. The lilies are used in vegetables and in flavoring meats. Their leaves differ in shape; the leaf of the night lily has a slit. Sipping our choice of sundown drink, we watched a pod of hippos come up for air. Shortly thereafter reed frogs began their nightly symphony, and Landy, our lodge’s pet crocodile, rushed home to beat the night. The staff met us with trays of Brown Old Sherry, a South African brand, which was superb.

Following a nightly tradition, our chef and a staff member introduced the dinner menu in two languages, so as to acquaint us with the local one. The dishes excelled in both taste and presentation — sweet potato soup decorated with dribbles of sour cream, ostrich steak with pasta, acorn squash stuffed with cauliflower and carrot, and chocolate crepes. I was so amazed at this spread that I had to ask where local men received such culinary training. They are all trained by Wilderness Safaris for employment at the concessions.

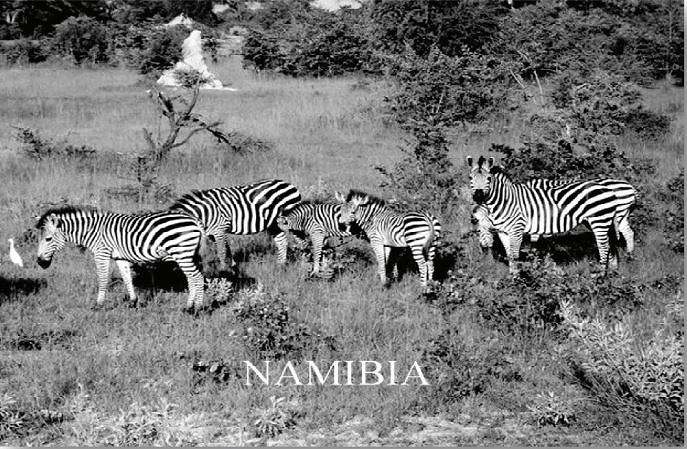

Early the next morning was our first game drive in this region, known as the Caprivi Strip, an elongated panhandle in the far northeast of Namibia. The flat strip, fed by multiple rivers, is the wettest region in an otherwise arid country. We drove through woodlands, passing by groups of zebras and impalas near watering holes. These animals benefit from each other’s strengths in detecting danger; zebras have good eyesight, and impalas a strong sense of smell. Huge termite mounds popped up randomly like sculptures shaped in clay, some with trees growing out of them. After mating, male and female termites start a colony, quickly growing in numbers. Thousands of workers build the mound, which is later flooded with heavy rains, so that the termites drown. Mounds with escape holes are deserted homes, which benefit other wildlife. Birds perching on the mounds drop seeds, thus giving life to new growth.

Adding excitement to our adventure, we got stuck in mud crossing a big puddle. Our driver was able to free the land rover by putting branches under the wheels as he jacked up the vehicle. Meanwhile, our guide, Mado, entertained us by making music with reeds. He used the sharp edge of one to slice another into various lengths, each making a different sound. This was a skill he had learned as a child growing up in the bush. Boys also made whips or ropes by braiding strong tree bark, and ate larva attracted to mopane trees, also called “butterfly trees” because of the shape of their leaves.

The next morning we visited a village and a local school. Namibian villages are made up of groups of extended families living in homesteads, each consisting of individual huts that grow in number as boys marry and build their own homes within the compound. Huts are made of mud plastered over branches, and water is drawn from a well. Several homesteads form a village with a headman. A chief is paid by the government to rule over a province made up of villages. Disputes are resolved first by the headman, then the chief, and finally the police. Mobile eye and dental clinics visit villages and schools.

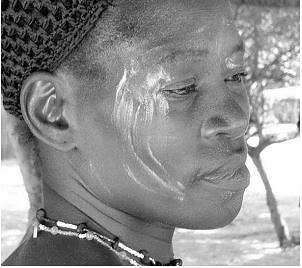

Tribal beauty marks

A visit to a historical village introduced us to traditional ways no longer widely practiced. We watched a woman seated in the center of a semicircle go into a trance as a shaman danced and drummed around her, building up to a frenzy. Blacksmiths used billows to keep a fire going while they shaped scrap metal into spears and hunting tools. In the center of one hut was a tall circular basket, which people used for grain storage by covering it with grass and sealing it with mud from termite mounds. A trap weighted down by mud patties was set outside the hut to protect the grain from mice. Using a bare branch as a ladder, chickens climbed into the central coop at night, while a nearby wildcat trap kept them safe.

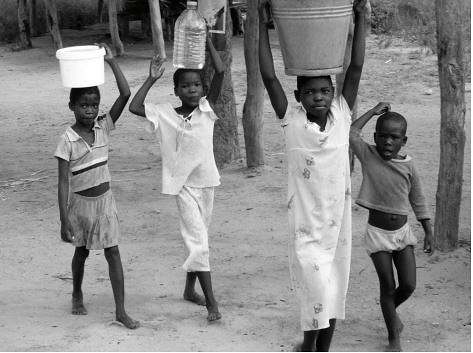

Our visit to a local school in a village of 300 people provided further insight. The school had 354 students, who walked through the bush to arrive. Classes were mixed for boys and girls, and accommodated approximately 35 students each. We visited the fourth and eighth grades; each classroom had students of varying ages and sizes. They were all learning English and invited us to look at their notebooks. Having no access to computers, they had mastered beautiful handwriting. During recess we met a Peace Corps volunteer on a two-year assignment to teach science. She mentioned that nutrition was insufficient in the students’ daily diet, which was based mostly on maize and sorghum. She also said that 50% of the village population were HIV-positive, with a funeral nearly every day. People died mostly of AIDS or malaria. The volunteer herself had contracted malaria a few months after arrival and had to travel twelve hours to receive treatment. She planned to go to medical school after the Peace Corps, and return to Africa to practice medicine.

We had two informative lectures on Namibia — one on its history and economy, the other on the Caprivi Strip. The early inhabitants of Namibia were nomadic Bushmen, who followed animals for sustenance. Eventually they were chased into the desert by incoming tribes from other areas. Europeans did not enter Namibia until the mid-19th century, because the Namibian Desert runs along the Atlantic coast for 850 miles, acting as a shield against potential invaders. In fact, the name Namibia means “Shield.” So Namibia remained tribal land until missionaries arrived in 1840, followed by Germans looking for ivory in 1880. The land was taken over by Germany in 1890 and called “Southwest Africa.” Tribes were split as borders were established with neighboring Botswana to the east, Angola and Zambia to the north, and South Africa to the south. In 1914 the British took Southwest Africa from Germany and annexed it to colonial South Africa. Inspired by the liberation struggle in South Africa, people in Southwest Africa organized and fought for independence. They renamed the country “Namibia” and held elections in 1989.

The Namibian flag has five diagonal stripes — yellow for the sun, blue for water, green for vegetation, red for dignity, and white for peace. The economy is driven by mining, fishing, tourism, and farming. Diamonds were discovered in 1908 during work on the Dutch railway. The value of a diamond is determined by the “four C’s” — cut, color, clarity, and carat weight. Also mined are copper and uranium. Tourism is the largest and fastest-growing industry. Fishing is concentrated along the Atlantic coast.

The Caprivi Strip is being developed for tourism. This narrow panhandle originally belonged to Britain. German Chancellor Leopold von Caprivi, in a bid to gain access to the Zambezi River, negotiated with the British for the strip, which was then given his name. After World War I it was returned to the British, finally becoming part of independent Namibia in 1989. 12,000 people from eight different tribes used to live all over this region. They were relocated, however, in order to create Mudumu National Park, an important initiative to preserve wildlife and encourage tourism.

During a final pontoon boat cruise, our guide treated us to garlands and necklaces he made from water lilies. We spotted eagles on trees and hippos in the dusk, treasuring yet another spectacular sunset. The chef outdid himself for our goodbye dinner — pot au feu with eggplant, carrots, onions, and cloves; polenta; baked sliced squash with thyme; and for dessert yogurt mousse with apricot sauce. The talented staff danced and drummed for us. Afterwards, over a cup of tea of our choice, including tea made from russet bush willow, we gazed at stars in the expansive midnight blue overhead, thus ending our memorable trip to Namibia.

Children carrying water