March 2010

Myanmar* was a pre-trip on an itinerary called “Ancient Kingdoms: Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia” organized by Overseas Adventure Travel, an agency which promotes solo and small group travel. Although I had been to all of these countries but Myanmar and Laos five years earlier, I decided to return to this fascinating region. At the end of the trip, I broke away from the group to visit friends who live in Bali, Indonesia, thus adding a sixth country to my journey. Each of the countries I was to visit requires a visa for Americans, necessitating a long lead time and many blank passport pages.

* In 1989, the military regime in Burma changed the country’s English name to “Myanmar.” They also changed the transliteration of many names, including that of the main city, Rangoon, which became “Yangon.” Many governments, organizations, and media bureaus reject the new names. Their use here reflects current official practice rather than support for the regime.

Bangkok Airport serves as a hub for most international flights to Southeast Asia. To reach my destination in Myanmar, I flew Delta Airlines from Boston to Minneapolis to Tokyo, and then on to Bangkok, where I spent the night in order to fly to Yangon the next day. After a total of 22 hours in the air, I arrived in Bangkok at 12:30 am, having lost a day by crossing the international date line. The thermometer read 27º C.

The new Bangkok International Airport is spacious and filled with specialty shops. It dazzles the eye with colossal mosaic sculptures, and offers efficient 24-hour service. During the hour-long flight to Yangon on Bangkok Airways, we were served a delicious hot lunch featuring three kinds of organic rice — white jasmine, red fragrant, and black fragrant — produced by an agriculture project in affiliation with the airline.

It was 37º C in Yangon (Rangoon), the former colonial capital. Jan, our Burmese guide, met the five of us who had signed up for the pre-trip. He wore a longyi, a unisex sarong-like garment favored by most locals. The Kandawgyi Palace Hotel, located by the royal lake of the same name, was our home base for two nights, at the beginning and again at the end of our trip to Myanmar.

Reclining Buddha

Our tour of Yangon began with a visit to the Chaukhtatgyi Pagoda with its 225-foot-long reclining Buddha, who has 108 marks on the soles of his feet. By worshipping these marks, which represent different worlds, believers remember that the Buddha is endowed with the attributes of chief of the world and is all-knowing. Here we observed many monks praying and people using little buckets to water small Buddha statues for purification. 89% of the population are followers of Theravada Buddhism.

A walking tour of downtown centered on the 2000-year-old Sule Pagoda and the surrounding area, which has houses with tiered golden roofs along with British colonial architecture and tall modern structures. Decaying old buildings which have turned into slum houses occupy blocks with other structures used as government offices. Food vendors on sidewalks, women carrying bundles on their heads, advertisements painted on public buses, billboards, and laundry-filled balconies on apartment blocks all contributed to the visual cacophony of the old town. As day turned to night, golden pagodas lit up, creating a magical nightscape.

Although our two-day sightseeing had to be split between the beginning and the end of our Myanmar visit due to an itinerary change, I will cover all of Yangon here, in order to keep my impressions of the city together. Old Yangon is the business center, where most buildings are in need of repair. Traffic, noise, dirt, and heaps of trash are part of daily life, whereas suburban developments with villas, which constitute New Yangon, are quite a way from the center. In Myanmar there are rich and poor; a middle class does not exist. Since 1962 the country has been ruled by a military dictatorship; the generals are among the wealthiest citizens.

A market visit took us through narrow alleys with small stalls jammed with goods. The currency in Myanmar is the kyat, and the official exchange rate is seven kyat to the US dollar, which commands a much higher rate on the black market. Since the dollar is accepted everywhere, I did not have to change money. I bought a T-shirt imprinted with the Burmese alphabet, which has 32 letters. Burmese is the principal language of 70% of the population, whose origins are in the Gobi Desert in Mongolia, with an additional 135 officially recognized ethnic groups. Burmese belongs to the Sino-Tibetan language family, though many Burmese words derive from Sanskrit, an Indo-European language.

Walking along the waterfront at the end of the day provided a glimpse into a different aspect of daily life. Commuters crowded into ferryboats to cross the shores of the Yangon River, a tributary of the Irrawaddy. Vendors did brisk business as workers crowded around low tables with stools, enjoying food and camaraderie without the intense heat of the day.

Entrance to Shwedagon Pagoda

The Shwedagon Pagoda is the cultural and spiritual heart not only of Yangon, but of the whole country. Believed to house relics of the Buddha, including four strands of hair, the sacred site attracts pilgrims, who come to venerate the Buddha and to meditate. The shining golden beauty of the pagoda is simply enchanting. Traditionally gilded since the 15th century, it is decorated even today with gold leaf laid by pilgrims. An estimated 100 tons of gold adorn the pagoda, which rises 322 feet above its base. The lower parts are covered in gold leaf, the upper parts in gold plate.

Faithful pouring water over Buddha

Covered stairways on all four sides of the large complex lead to a marble platform, on which the pagoda stands. Vendors sell devotional objects and souvenirs along these steps. In the middle of the platform stands the main stupa (Buddhist reliquary), surrounded by four large and 64 smaller stupas. Among the many structures on the platform are shrines flanked by planetary posts, each dedicated to a different day of the week. Here people born on the day corresponding to each post offer prayers and pour water over the Buddha and the appropriate animal. For instance, people born on a Monday have the tiger as their animal sign and pray by the planetary post for the Moon. From the many pavilions comes a soft murmuring of prayers, while others meditate and make offerings to nat spirits to ask for protection and good fortune. It was at this holy site that monks began their protest march in September 2007.

Chinatown, with its bustling market, was another window onto local culture. With the approach of Chinese New Year, the streets were decorated with lanterns. Nuns in pink robes collected food from the various market stalls, while shoppers mingled among vegetables, fruit, poultry, and baskets of quail, duck, and chicken eggs preserved in lime or mud — all considered delicacies, as are fertilized eggs. Men spun thin round sheets of rice dough in the air, flipping them onto hot iron sheets to make spring rolls. Some vendors carried goods on their heads; others spread theirs out on the sidewalk. Since there is no refrigeration in homes, people shop daily and consume many dried or preserved foods. The array of dried fish in the market was amazing. From small round eggplants to large jackfruit with drainable sap to a cosmetic white powder made from tree bark, the market visit offered many discoveries.

The National Museum, where no photography is allowed, displays the history, culture, literature, and ethnic makeup of Myanmar. Displays include royal costumes, early toys, marionettes, baskets, and other crafts. The Lion Throne of Myanmar’s last monarch, King Thibaw, which was smuggled out to India by the British, was given back at the time of independence and now graces the ground floor of the museum. There is also a maquette of the royal palace, which was burned down by the Japanese during World War II; it has been reconstructed using old photographs.

Burmese food is mild and delicious. Standard fare is soup, steamed vegetables, fish or meat, and rice, with fresh fruit for dessert. Among our memorable meals was dinner at the Sakura Sky Lounge, where we enjoyed grilled fish over a bird’s-eye view of the city by night and lunch at a Chinese restaurant, where our first course was fish balls and quail egg in clear broth. Breakfast spreads were Asian-style — soup, steamed or pickled vegetables, potatoes gratin, noodles or rice, and eggs or meat. There are no dairy products in the Burmese diet; condensed milk is imported from Thailand. While cereals were hard to come by, delicious omelets cooked to order were always available.

Upon arrival at the airport to fly to the city of Bagan, we found that our flight was delayed due to “fog” at our destination. The 2-hour delay was an opportunity for us to observe the locals in their finery. Women with slight build and dark hair looked beautiful in longyi with flower patterns. Men wore longyi with stripes or checks. These colorful wrapped cloths were complemented above the waist by jackets made of fine textiles. Two TV screens showed nonstop commercials promoting glamorous looks with shampoo, make-up, silken hair, and similar products.

Finally in Bagan, we learned that the poor visibility which had delayed our flight was actually the result of slash-and-burn farming in the central part of the country. Before the monsoon rains, farmers burn their fields to enrich the soil, covering the skies with smoke. Waiting for the smoke to clear is standard airport procedure during certain months of the year. Despite the haze, Bagan still offered many highlights.

Founded in 849 on the banks of the Ayarwaddy River, Bagan is located in the central part of Myanmar, which is the largest country on the Southeast Asian peninsula, almost three times the size of Great Britain. As we approached Bagan from the air, its savannah landscape stretching for miles indicated a hot, dry climate. At the airport, a display of umbrellas made of bamboo and hand-painted fabric in floral designs promised a city rich in traditional crafts. Our sightseeing began right after our arrival with a walk through a local market in the district of Nyaung.

The sprawling street market covered everything from food to clothing to household goods, mostly spread on the ground or on makeshift crates. Earthenware pots, heaps of fresh and cooked food, lacquerware, bamboo art, and stacks of beautiful clothes sold for a few dollars an item. The country’s widespread poverty, with many barely scraping a living from the land, was evident from the vendors’ desperate desire to sell. I made two of them happy by buying a longyi and a bamboo picture frame.

Shwezigon Pagoda

The splendor of the pagodas stands in stark contrast to the visible poverty. The Shwezigon Pagoda is especially impressive. The first to be built in the characteristic Burmese style, this pagoda consists of three square terraces with stairways leading up to the bell-shaped main body of the gilded stupa, with rings tapering up to the top. In addition to this enormous weight in gold, Buddha statues large and small in surrounding shrines continually glow, as worshippers layer them with gold leaf. In the nat shrine here, the first of its kind in a Buddhist pagoda, there are 37 nats (spirits) to venerate in addition to the Buddha.

The most impressive masterpiece of architecture in Bagan is the Ananda Temple, built in around 1090. At the four corners of its square base are porticos leading to passages into the interior; at the end of each portico is a ten-meter-high glowing statue of the Buddha. The four corners of the temple are guarded by lions, each of which has one head and two bodies. The top of the temple soars to a height of 167 feet and is crowned by a gilded tower, called a shikhara.

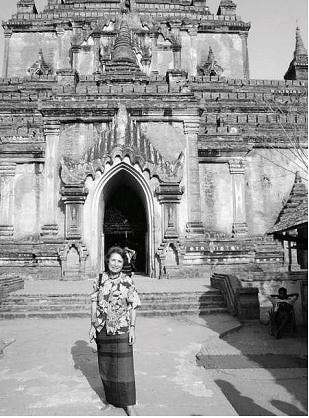

In my longyi in old Bagan

After lunch and a brief rest at our hotel, the Aye Yar Riverview, we went back out to explore more temples in old Bagan, which boasts 4000 temples and pagodas and is a UNESCO heritage site. I wore my new longyi, as covered legs and shoulders with no footwear are proper attire for visiting sacred sites. The Sulamani Temple stood out with its frescoes of Buddha images and of stories from the Buddha’s life, though many of the frescoes are deteriorating.

The ancient pagodas are spread over a fifteen-square-mile area; several are situated outside the city walls in order to provide spiritual protection for Bagan. The common modes of transportation taken to see these are the horse cart and the bicycle. We rode a horse cart to Shwesandow, also known as the Sunset Pagoda, as visitors gather here to take in a fantastic view over the temples and the Ayarwaddy River. At sunset the pagoda was hopelessly crowded. I managed to climb up to the second of its four square terraces, which give it a pyramidal form. The view was indeed fantastic. The landscape radiated an almost unearthly beauty in the soft light of evening. Our day ended with dinner at a riverside restaurant. We enjoyed curried fish and beef with rice, eggplant, and salad. Waiters delivering the meal with lit torches in their hands added to the spectacle of the setting.

Pagoda landscape

Early the next morning was a much anticipated hot air balloon ride I had signed up for. I was picked up at the hotel at 5:45 in an old British army vehicle, which the company Balloons over Bagan had purchased from the government in order to transport passengers. After tea and cookies and safety instructions, we climbed into the balloon basket —twelve passengers, three per section.

The hour-long ride over ancient Bagan and its pagodas at sunrise was spectacular. We hovered over pagodas large and small, seeing their architectural detail at close range, waved to locals cooking breakfast outside of their thatched bamboo houses, and learned about crops — rice, onions, peanuts, and sesame — grown at the edge of the river. The locals harvest these crops before the river rises with the melting of the snow in the Himalayas. Our British pilot was well informed and gave us a wealth of information, including an explanation of the controversy between residents and UNESCO, which wants to move their houses back to protect the heritage site. Our adventure ended with a champagne toast upon landing.

At the TUN lacquerware workshop we learned about Myanmar’s finest art form. Lacquer is made from the sap of the thitsi tree, which grows wild in the northeastern part of the country. The sap is collected by making a shallow V-shaped cut in the bark and allowing the liquid to drip into a bowl at the bottom of the incision. Various substances are mixed with the sap to create lacquer of different colors. The base of a lacquerware object is made of thin strips of bamboo coiled into circles, each of which is placed inside the previous one at a slightly higher level. Notched edges keep the strips in place. Lacquer mixed with ash fills the spaces between the coils. After receiving several coats and drying in between over a period of three days in a humid cellar to prevent cracking, the piece is polished. Objects with decorations, such as colorful incised designs and gold leaf patterns, require additional work. The time needed to finish a piece depends on the number of colors used. Objects range from Buddha images to bowls, vases, boxes, stacked food carriers, cups, and trays. The results are all exquisite.

Mount Popa — popa means “flowers” in Sanskrit — is a 4980-foot extinct volcano located 32 miles southeast of Bagan. On the way there we visited a palm sugar farm, where all the trees had bamboo ladders attached to their trunks. Men climbed trees with earthenware pots tied to their waists, exchanging empty containers for ones filled with palm juice. Women stirred the juice over a fire until thick, then shape it into small balls of sugar. Nearby an ox drove a stone mill, which ground peanuts to extract oil. Palm leaf handicrafts and a bamboo restroom with a facade of intricate woven patterns were delightful.

To the southwest of Mount Popa is the volcanic peak of Popa Taung Kalat, which is said to be the home of the nat spirits who protect the mountains, and is therefore one of the most important sites for nat worship in Myanmar. A covered stairway with 700 steps leads to the Temple of Sacred Spirits, 2554 feet above sea level. Leaving our shoes with an attendant at the bottom of the stairway, we began our climb, accompanied by monkeys begging for bananas, nuts, and sweets. Vending stalls flanked the steps, which were crowded with pilgrims carrying offerings of flowers and food. The shrines carried a dazzling assortment of mirrors, neon lights, bright colors, gold leaf, and plenty of money to appease the spirits, who can do a great deal of damage if crossed. Once at the peak, we enjoyed a panoramic view of the surrounding mountains, including an imposing monastery on top of Mount Popa.

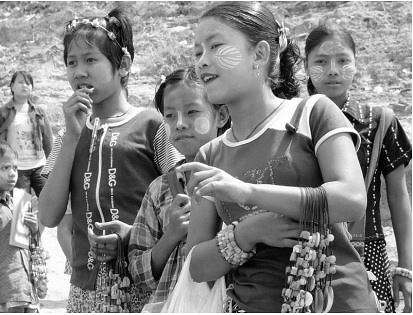

Young vendors

at the dock

A sunset river cruise was yet another window onto local life. By the boat dock, children hawked postcards, bracelets, shirts, and longyis. Some women washed and spread laundry by the river’s edge, while others dug up sand in buckets, which they carried to barges on their heads for transport to construction sites. The setting sun silhouetted pagodas in the distance and trees with exposed roots near the shore. Fishing boats grew dark as the waters shimmered in the last glow of the sun.

The last thing we did in Bagan was to attend a marionette show. In a society where natural and supernatural easily overlap, puppets occupy a place between humans and spirits. These puppets represent easily identifiable mythological characters, both animal and human. They use refined courtly language and share the stage with a puppeteer in full view. The accompanying singers and orchestra are an intrinsic part of the troupe. In the face of modern movie and TV entertainment, this ancient fine art only survives due to the continued interest of foreign visitors. I was one such admirer. After seeing the richly dressed, well crafted marionettes, I decided to look for one to take home. Jan, our trip leader, suggested I wait till I arrived in Mandalay, as we would be visiting a village famed for its marionette craftsmanship.

A 30-minute flight with Air Mandalay brought us from Bagan to Mandalay, the royal city, founded in 1857. On the way into town we made a detour to Inwa, the former royal capital, founded in 1364 and known for its unique monasteries. Passing by child cattle herders and young vendors of straw hats, bracelets, and postcards, we reached the dock to cross the Irrawaddy River. As in other places we had seen, the banks here were lined with people scrubbing laundry over stone slabs. Transferring to a horse and carriage, we bumped along a dusty country road, admiring small houses on stilts with facades woven from alternating strips of dark and light bamboo.

Inwa Temple

Our first stop on the carriage ride was at the ruins of the 13th-century Inwa Temple, made up of tiered brick structures embellished with stone animal statues. Not far away stood the impressive Bagaya Monastery, built entirely from teak in 1834. The structure has 267 columns made from teak tree trunks, the tallest 60 feet high and 9 feet round. Another 19th-century monastery, Mahar Aung Mye Bon San, stood out with its multiple roofs and a seven-tier prayer hall.

Back in the city we had a delicious lunch at a restaurant called A Little Bit of Mandalay, which specialized in Burmese cuisine. Here we enjoyed fish and chicken curry accompanied by rice, watercress, and green beans. Finally at our hotel by the Red Canal, we were met by friendly staff, who greeted us with broad smiles and very welcome moist hand towels for cooling off. Set amid lush tropical greenery, with a moat and traditional furnishings reflecting Myanmar’s multicultural heritage, the boutique-style hotel accentuated the unique elements of the country. I later found out that this building had been the Chinese Embassy before being transformed into a hotel.

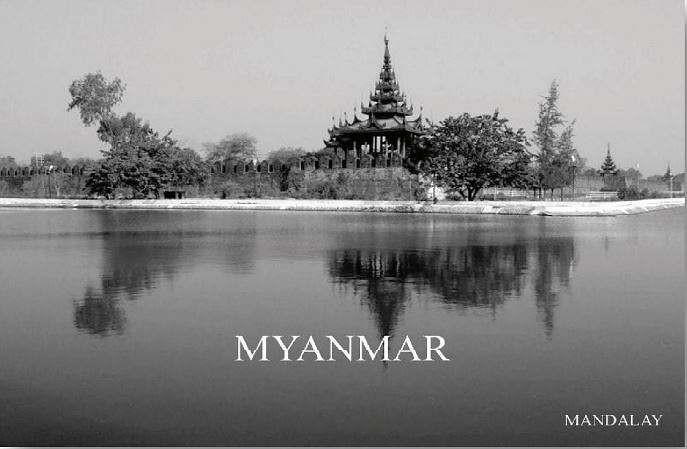

After a rest in what was to be our home for the next two nights, we went back out to explore the city, starting with the former Royal Palace. A landmark of the city, the palace complex was built in 1887 for King Mindon. Surrounded by a moat three kilometers long, the complex is situated right in the center of Mandalay and is a reminder of the final years of the Burmese kingdom. The palace, made of teak, was burned down by the Japanese in 1945. The government has rebuilt it using modern materials; however, it is now used by the military and, therefore, is not open to the public. In 1994, 20 citizens of Mandalay were made to clear the moat of mud — a form of forced labor imposed by the regime.

The Shwenandow Monastery is another all-wood building which, fortunately, has survived the ravages of war. It has tall teak columns, ornate carvings, and small relief sculptures on all the door panels. The Kuthodaw Pagoda, with its 729 marble slabs, is home to the largest book in the world. King Mindon employed 200 craftsmen for 7½ years to carve out the work, known as the Pali Canon, on these slabs. Completed in 1868, each of the slabs has its own whitewashed stupa. In 1871 Mindon convened the Fifth Buddhist Synod in order to consolidate the faith and unite Burmese Buddhists. A team of 2400 monks recited the complete text over a period of six months.

Whitewashed stupas of Kuthodaw Pagoda

Mandalay Hill is located in the north of the city; it offers a panoramic view of the surrounding region — individual homes to the east of the Red Canal, and the crowded south and west, where most people live. It is a favorite place for visitors to watch the sun rise or set. We drove to the hill and then climbed 90 steps to the top, crowned by the Su Taung Pyi, or Wish-Granting Pagoda. The pagoda was dazzling, with its shimmering mosaic walls and its multitude of arches supported by mirrored turquoise columns. People filled glittering shrines to pray for the fulfillment of their wishes. My only wish was for the smog to clear so that I could get a good picture of the panorama below as the sun set. My wish was not granted.

Our hotel by the Red Canal had a welcome party for its guests on a timber-lined deck by the pool. The full bar included rum or gin mixed with our choice of tropical fruit juices. On an outdoor brazier a chef grilled fresh corn, giant okra, and broccoli, and skewered small potatoes on demand, while gracious staff waited on us tirelessly.

The next morning’s local color included people exercising by the canal and saffron-robed monks crowding into pick-up trucks to go to the market and collect their daily meal. We rode a boat up the Irrawaddy River to the village of Mingun to have a glimpse of the local culture. During the hour-long boat ride, we passed by sandbanks dotted with people living in shacks, some under bamboo mats fastened to posts by the edge of the water. These people make a living by shoveling sand straight into a boat and rowing it across the river to sell to construction sites. In this region live the poorest of Mandalay’s poor.

In Mingun we visited a monastery school, where young boys received basic education. Often parents entrust their sons to such a school to keep them away from the influence of drugs. Myanmar has been responsible for the world’s largest production of raw opium and today ranks second to Afghanistan in yearly volume. Opium is grown in the state of Shan in the northeast. We observed young boys with shaven heads relaxing in the schoolyard and having lunch in the dining hall.

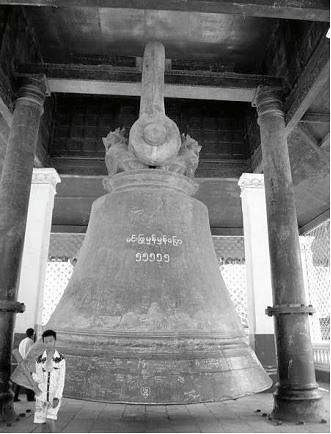

World’s largest bell

The Mingun Pagoda is the largest temple in Myanmar. Even approaching the town by boat from a distance, one can see the massive ruins of the pagoda. Built more than two centuries ago during the reign of King Bodawpaya (1782-1819), the temple was damaged by an earthquake 20 years later. Nevertheless, the remains of the brick edifice, 164 feet high and 236 feet wide, are spectacular. From the top there is a magnificent view of the river.

Mingun is also home to the world’s largest working bell, which is three times as tall as a person. The Mingun Bell was cast in bronze in 1808; once it was completed, King Bodawpaya had the master craftsman executed in order to stop him from making anything similar.

Built by King Bagyidaw in 1816, in memory of his favorite wife, is the impressive Hsinbyume Pagoda on the northern edge of Mingun. Its striking architecture is based on that of the Sulamani Pagoda on the mythical golden mountain of Meru, which is the center of the universe in Buddhist-Hindu cosmology. Seven terraces with undulating rails, representing the seven mountain ranges around Mount Meru, lead up the stupa; along the way are niches with mythical monsters standing as guards.

Mingun is also known for its production of marionettes. The town market is lined with stalls stacked with marionettes of all sizes and characters. I bought a used one of a queen, as I liked her delicate features and her faded red costume embroidered with silver metallic thread. The saleswoman did not seem to mind parting with one of her stock characters; she was happy with the $4 she received in return.

Lunch at a Chinese restaurant was wonderful. Soup with quail eggs and clear rice noodles in broth became my favorite throughout the trip. Sweet and sour fish and seafood with mushrooms were among the dishes, which were served on a rotating tray.

Applying gold leaf

to Buddha

Following lunch we visited a gold leaf workshop, which was easy to identify by the rhythm of hammers beating gold into wafer-thin sheets. Two ounces of gold bullion is first stretched into a ribbon ¾ of an inch wide and 20 feet long. Then it is cut into pieces of equal length, which are separated by paper made from bamboo. 200 pieces of wrapped gold make one unit. Each unit ultimately yields 720 flakes through repeated hammering and wrapping. Workers use six-pound hammers in stages of 30 minutes each. The final stage produces gold leaves, which are cut into squares and pasted onto paper made from hay, ready for packing and shipping. In addition to its extensive use in sacred places, gold leaf is used in traditional medicine and in make-up for fair skin.

Visiting the Mahamuni Pagoda, one of the country’s most sacred temples, right after the gold leaf workshop increased my amazement many times over. In the center of the glittering pagoda sat the Mahamuni Buddha, totally covered in gold leaf by pilgrims, so that some parts of the body were hardly recognizable. In places the layer of gold on this ancient statue is 12 inches thick. Every morning at 4 a ceremony is held, during which monks wash the face of the statue.

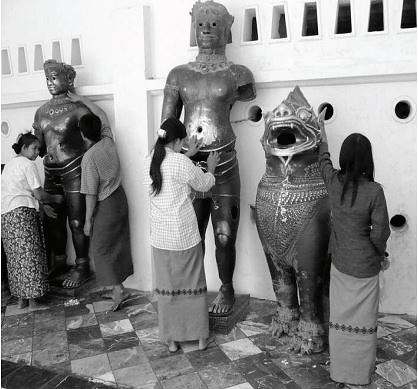

Rubbing bronze figures for healing

Also in the pagoda are six bronze Khmer figures, which are 800 years old and were originally enshrined in Angkor Wat in Cambodia. Brought to Thailand as war trophies, they were later donated to Burma in celebration of its victory over Britain. Three of these figures are lions, and two are temple guards who, according to folklore, can cure the ills of the faithful if certain parts of their bodies are rubbed. The sixth figure is a three-headed elephant, the mount of the Hindu god Indra.

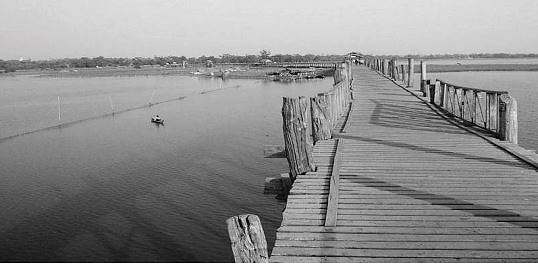

My last activity in Mandalay was walking on the world’s longest footbridge. I enjoyed the peaceful walk, viewing emerald fields alternating with fishing boats and traps on the tranquil waters that stretched on either side of me — an idyllic beauty etched in my memory.

The legendary “golden land” is still the Myanmar of today. Long cut off from the world, it is one of the most exotic countries I have visited. I enjoyed exploring and experiencing the mystical charms of the archeological sites, glittering pagodas, and wealth of cultures in Myanmar, not to mention its tropical beauty and, most of all, its gracious and hospitable people.

World’s longest footbridge

→ Laos