WESTERN SAHARA

Er-Rashidia is a garrison town 160 kilometers from the Algerian border. In 1975 360,000 people marched here to free the Western Sahara from French occupation. It has a big military presence now because of poor relations with neighboring Algeria, which wants access to the Atlantic Ocean. We drove by upright square stones erected as sand fences to Erfoud, a town at the edge of the Sahara. We transferred to Toyota land cruisers after purchasing long, colorful scarves from a vendor, who showed us how to wrap them as turbans. After another hour of riding in four cruisers with four passengers in each, we reached Merzouga, the first of two campsites. Our day’s journey took nine hours, with many photo stops.

Our campsite

Deep in the great Sahara was our private tented campsite, surrounded by waves of towering dunes. Arriving here at sundown, we had a glimpse of the sun as it disappeared behind the gigantic dunes. Since there was no electricity on the campgrounds, I relied on my flashlight to explore the site. My square tent was equipped with a cot, a mattress, and a sleeping bag. By the cot was a nightstand with a candleholder and two spare candles, a lighter, a cup, and enough space for my water bottle. A towel hung on a rope in the corner. I managed to locate the pillowcase we had been asked to bring, and got my sleeping bag ready with the liner provided for us. A tented outhouse was in the back.

The dining tent was well supplied with beer and wine, courtesy of our group. The camp staff served us soup, then couscous with meat and vegetables, followed by apples and oranges for dessert. After dinner we sat around the campfire and enjoyed the camaraderie of neighboring Tuareg nomads. The musicians played and sang for us, while some danced. As I walked back to my tent, the Saharan night sky above was a majestic open air spectacle. Putting on several layers, including socks, I slid into my sleeping bag at 10 pm and blew out the candle.

To watch the sunrise, the camp staff woke us up at 5:30 am for a climb to Erg Chebbi, which means “high dune” in Berber. Outside my door a basin of hot water for washing helped ease the morning chill. Waiting for us were pitchers of hot mint tea and coffee. At a distance I noticed the striking silhouettes of a row of turbaned men against the towering backdrop of Erg Chebbi, the highest dunes in Morocco at 900 feet. As we began our climb, they approached us to see if we needed help. Since refusing help would deny them a tip, I smiled back at a handsome young Berber with sparkling eyes and white teeth that complemented his dark skin. Conversing in French, I assured him that I would hold on to him if I needed help. About half our group made it to the top, as going uphill while sinking in the sand is a challenge. My companion held my hand during the final stretch.

Watching the sunrise from the heights of a sand dune is an utterly unique experience. As the sun came up, the panoramic view changed from dark gray to a glowing backdrop of rose pink, for a fantastic shadow play across the peaks and valleys of the dunes. Taking each other’s photo — I in my red parka and lavender turban, my guide in his jalaba and white turban — we were like actors on a movie set.

My Berber guide

On our way back my guide walked backwards as he pulled me by the ankles in a seated position. I was reminded of my childhood sled as we sped downhill, leaving tracks in the sand. At the end of this adventure my guide spread out his fossils, hoping I would buy a few. Unique to the region of Erfoud, these sea fossils go back 350 billion years. Once they locate the fossils, Berber families clean and polish them. I bought two, a sardine and a nautilus, making my guide very happy. He thanked me for helping him support his family.

Breakfast was ready upon our return. We helped ourselves from a spread of pancakes, apricot and fig jam, honey, omelet, orange juice, coffee, and tea. Both the pancakes and the eggs had the color of saffron, favored in Berber cooking. The eggs had been flavored with fresh cilantro — delicious. In the outdoor setting under the clear blue sky and the warmth of the early morning sun, this breakfast was memorable.

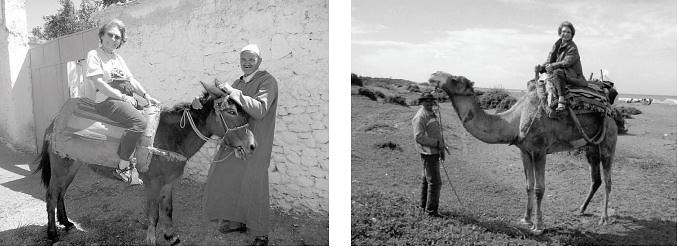

Our next venture into the desert was on the back of a camel. For about an hour we rode camels that were tied together in two caravans of eight, with two herders, one in front and one in back. The stillness of the desert was wonderful, while its surface displayed shadows, patterns created by the wind, and animal tracks — kangaroo mouse, fox, and beetle. Meeting up with our land cruisers, we headed to our second private desert camp with several noteworthy stops on the way. At the Kasbah, now a museum of Berber crafts, were rugs, calligraphy, embroidery, clothing, jewelry, saddlebags, and Jewish artifacts.

Kasbah

In Rissani we went to a ksar, where extended families live communally by sharing food, fuel, and other goods. This was an adobe complex with one gate to the outside, all others opening onto the fields. The community had its own rules and regulations, overseen by a council of elders. Because of intermarriage among 160 families from one extended group, the mortality rate is high. Children are promised for marriage at age 7; girls marry right after puberty. To discourage divorce, a groom receives a sacrificial goat. We visited a “date Berber” woman, who told us that she had had five children, but that only one had survived. She did not know her son’s age or her own age. She did not remember her mother, who had died very young. Her husband was sick in the hospital. Due to communal solidarity, virtually no one goes hungry or homeless in Morocco. Social problems are likely to arise if this solidarity disintegrates.

Our visit to a fossil factory was fascinating. From a quarry in the mountains large blocks of marble are excavated. At the factory they are sliced using a cutting machine with a diamond blade imported from Italy. At a rate of one centimeter an hour, it takes ten days to slice one block, revealing embedded fossils, which are 350 billion years old. After washing, the fossils are chiseled out and polished, first with an abrasive stone, then by hand with sand paper, and finally by buffing. The showroom featured beautiful marble tables with embedded fossils, along with small objects such as plates. Individual fossils were on sale as well. I bought a trilobite (three-lobed beetle), and one called a “desert rose” because of its pinkish color, formed by underground gypsum deposits.

We arrived at our second tented campsite, our home for the next two nights, deep in the sand dunes near Daya El-Maidar. The tents were arranged similarly to those at the first site, except that there were shower facilities. After happily washing off our dust, we assembled for a cooking lesson from the chef. We watched him prepare chicken tajine, spreading a marinade of olive oil mixed with cumin, paprika, ginger, and saffron under the skin and then cutting up vegetables for the slow stove-top braising of this dish. A lemon pickled in vinegar, salt, and water is added in the final fifteen minutes, along with olives. The succulence of tajines is due to the cooking pot — also called “tajine” — which has a heavy, shallow glazed dish at the bottom with a conical unglazed lid inside. As the steam rises, the clay absorbs much of it, thus reducing the amount of cooking juices.

In the morning we took a walk to the tent of an Imazighen, which means “free man” in Berber, and brought staples — sugar, coffee, chickpeas, and lentils — as gifts. The women in our group presented these gifts to the widow we visited. A mother of five children, three of whom she had delivered alone, she received us with her oldest son, aged fifteen. Veiled and dressed in black, she was spinning wool. A silver fibula necklace crossed her chest, indicating she was married, as opposed to those worn on one side by single women. She was shy and looked down, even after the men in our group had left. In a nearby tent we visited a woman with two little children, who were helping her to card wool.

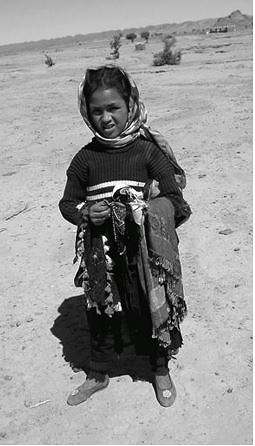

Berber girl selling crafts

Outside men sold fossils; women sold crafts — dolls, beads, and tie-dyed scarves fringed with brightly colored yarns and sequins. Imazighen nomads live for the day, rather than worrying about tomorrow. The objects in their daily lives speak of a culture rich in beauty and spirituality. Their tents are made of wool from young camels less than ten years old. Narrow strips woven on handlooms and sewn together become watertight with the swelling of the knots when it rains. Due to the scarcity of water in the environment, ablutions are performed using sand. The most common health problem is lung disease due to dust inhalation. Major sandstorms occur during the fifth and ninth months of the year.

Returning to our campsite, we crossed a vast, bumpy stretch of land. On the right were dunes in varying colors of ochre and rust, casting shadows as the sunlight hit their peaks and valleys. On the left was rocky terrain, with patches of greenery indicating water. We stopped at the top of the dune nearest our camp to admire the spectacle of the lower dunes. Knowing that the Sahara stretches 2600 miles across Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Mali, Sudan, Ethiopia, Egypt, and Jordan, I felt the magnetic pull of the dunes in their majesty.

Back at camp, Aziz gave a lecture on the basics of Islam, which consist in submission to God as manifested through the gestures of prayer. The five “pillars” of Islam are: proclamation of one God; five daily prayers with a message — at sunrise, at noon, in the afternoon, at sunset, and at night; zakat, or alms, which means giving 2.5% of one’s money to the poor; Ramadan, a month of fasting from sunrise to sunset in order to appreciate the hunger of the poor; and Hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca, to cleanse oneself of sins. A mosque is the house of God. An imam is a theologian who knows all 60 chapters of the Koran by rote and leads prayers. Of the 1 billion Muslims, 18% are Shiites — followers of Ali, son-in-law of Muhammad; the rest are Sunnis.

Before dinner Aziz led another walk into the dunes, carved by the winds into crescent or round shapes, where we each picked a spot to meditate. The wind-rippled surface of the sand was hypnotic — a welcome solitude in the middle of our fast-paced adventure. We spent our final evening watching the brilliant stars in the night sky. In the morning our staff of eight Berber men, who had taken excellent care of us at both camps, played tambourines and danced for us as they merrily sent us on our way. Departing on foot, we crossed the desert plain and stopped at a Berber cemetery to learn about funeral customs.

A Berber grave is 1 meter deep and 20 centimeters wide. The body is wrapped in a white shroud with the head turned to the right, then covered with dirt. Two stones — one at the head, one at the foot — mark the grave; bigger stones are reserved for the chief and his son. Customarily rose water is sprinkled over the grave. Women do not attend burials, but stay home for three days. They wear mourning clothes for four months, and may not remarry for three.

Driving by mud houses, date palms, and waving barefoot children, we arrived at the farm of an extended Berber family. We walked through wheat fields, learning about henna plants and alfalfa, which is grown as animal feed. We tasted fava beans in addition to more familiar carrots, onions, and turnips. The self-sufficient farmers in this family also made dairy products.

Farm children attended a one-room schoolhouse built by four Berber families. Their teacher, Halit, a 24-year-old man, met us at the door and had the students greet us in Arabic. The mud schoolhouse had one door and two windows, which provided natural light, plus a blackboard in between. Students, three per desk, sat by grade from left to right in two rows. We squeezed in with the children at their desks, as there was no room to stand. All the children were six years or older, with the older girls wearing headscarves. Nine were already in third grade studying math, science, reading, writing, Islam, art, physical education, and first-year French. They sang Un petit chat for us, and we sang Old MacDonald Had a Farm for them.

By bus we drove to the oasis town of Tineghir, crossing the Anti-Atlas Mountains, which face the High Atlas, at 4000 feet. The terrain turned to mossy slopes with goats; rocks became boulders. Set against the crest of the mountain, Tineghir matches the pinkish glow of its surroundings. Buildings have flat roofs, with turquoise or blue-framed doors and windows. When adobe houses deteriorate, new ones go up. Settling here overnight, we washed off our desert dust and welcomed the altitude-tempered warmth.

Cafes surround Tineghir town center. Men of all ages sit here to watch the world go by. We joined them over a cola. Cigarette and candy stands under umbrellas, street vendors, and shoeshine boys vied for attention. An Internet cafe was full. We walked through the market where locals shop for household goods. I bought a green and red striped cloth with little pompoms at either end, which women wrap about their waste as an apron. We also strolled through the red light district, where many young girls who do not observe traditions at home end up as prostitutes. Rejected by their families and with no other place to go, they sadly sit in windows waiting for customers.

With students of Dar et-Taleb

Dar et-Taleb is a subsidized boarding house for poor children. 120 boys from the countryside, aged twelve to twenty, live here while attending school, until they pass the baccalaureate to enter university. Said, one of eight siblings, took us on a tour. In addition to Imazighen, he spoke Arabic, French, and English. He hoped to become an engineer. He showed us the dormitory, his locker next to his bed, the study hall, a computer classroom, the library, and the dining room. The menu of the day, prepared by the doctor of the institution and cooked by women, was chickpeas with tripe, bread, and oranges. Accustomed to tripe dishes in Turkey, I recognized the kitchen smells, which were unfamiliar to the rest of our group. We enjoyed mingling with the students; some asked us for Arabic-English dictionaries. They were allowed to watch TV on weekends and liked going to soccer games. They had never seen the ocean.

Women washing in the river

On the way to Todra Gorge, we passed by women doing their wash in the river and spreading it over shrubs to dry. Lunch was at the base of the gorge, with craggy rock walls looming 1000 feet over a lush narrow valley of date palms and grain fields. A great treat was a visit to the Berber Artisan House. Our Tuareg host in blue garb welcomed us over fresh mint tea, which we watched him prepare. Assembled on trays were green tea, chunks of beet sugar, fresh mint, two teapots, and clear glasses. After washing the tea in a pot of boiling water, our host placed all the ingredients in the other pot over a brazier. Then he pumped air onto the coals to simmer the tea. A Berber bellows, decorated with mirrors, is generally used by women in the kitchen when men are not around, and covered up in their presence. Sugar is added to mint tea during preparation, making it quite sweet. Receiving tea without sugar means one is not welcome.

Serving tea is a ceremony. The pot is held high up while the tea is poured with great virtuosity, filling a clear glass up to its gold-glazed band. As we enjoyed our tea, we had an introduction to Berber crafts and carpets, all of which are made using natural dyes — henna for red, saffron for yellow, mint for green, kohl for black, and so on. We admired a sack made of camel leather; tent stakes carved from cedar; swords; and jewelry made of amber, coral, and silver. Berbers do not wear gold because of its elitist associations.

Beautiful rugs and carpets filled with characteristic symbols of the village, or douar — such as keys, doors, and eyes — were unrolled before us. The color indigo represents the sky. Unlike most other rugs, which are either knotted or woven, Tuareg ones combine the techniques of knotting, weaving, and embroidery. They are only fringed at one end. Although I have beautiful Turkish kilims, I could not resist buying a small Berber carpet, in addition to a necklace made of camel bone.

My henna adornment

At a home visit we had a demonstration of the regional henna custom for adorning women, especially new brides. The henna plant is native to North Africa. Crushed and powdered dry leaves mixed with water make a thick paint, which is applied to the hand with a syringe to draw designs. After the painted palm is dried over a brazier, the henna is fixed by sponging onto it a mixture of crushed garlic, lemon juice, sugar, and pepper. Scraped the next day, the palm reveals a deep orange design. Six of us picked traditional patterns and had our hands adorned. Mine had a big eye in the center to ward off evil; it lasted about two weeks before wearing off. In keeping with our Moroccan adornment, we had dinner at our hotel under a nomadic tent, which was totally covered with rugs from ceiling to floor, with mirrored ones on the walls.

On our way to our next overnight stop, Quarzazate, we drove to the Dades Gorge, shaped by the river that irrigates the Dades Valley. Admiring emerald-green fields and fig trees, we climbed to 7350 feet past breathtaking peaks, valleys, and giant sandstones which locals call the “brains of the Atlas.” Blended into the mountainside, red clay houses with windows small enough to let the light in distinguished themselves by their colored doors. Young girls with head covers carried big bundles of firewood and animal feed on their backs. A slogan saying “Western Sahara is ours” stood out against the mountainside. We stopped at a Sunday market crowded with goats and sheep sold for breeding. Bargaining was brisk and animated. Whereas Friday is a holy day, Sunday is a big market day.

Next we visited a Berber family for tea and homemade bread. The eldest daughter, confined to hard work, sat in a smoked-filled kitchen, only her eyes visible through her head covers. After a three-year marriage her husband had divorced her because she could not conceive, thus dishonoring her family. We watched her chop vegetables and place them in between two pieces of rolled-out dough, which she then baked in a flat pan over an open wood fire. While waiting for the pizza, we visited her mother over tea, walnuts, almonds, and fresh bread dipped in olive oil and honey from mountain flowers. Everything was delicious.

In Boulmane we called on the imam at his kasbah. The imam, who preached in Arabic, did not speak English, but generously hosted us for lunch. After washing our hands from a kettle of warm water poured over a brass bowl, he served us lentil soup cooked in mutton broth. We sipped our soup directly from bowls, which he filled from a large tureen. There were no utensils at the table. The main dish was gasaa — couscous steamed separately, then added to a pot of chicken with vegetables, cabbage, carrots, squash, and turnips. The imam showed us how to eat the dish by rolling the couscous into a ball with our right hands and popping it into our mouths. Dessert was bananas and tangerines; we left the peeled skins on an oilcloth, which our host gathered to shake out in the kitchen. Mint tea completed our lunch.

Marriage is required in order to become an imam. Our host’s wife joined us after lunch to help dress a bride, who volunteered with her husband to go through a mock ceremony for us to understand more about a traditional marriage, which is formalized by signing a contract drawn up by the imam. In Morocco a couple cannot take a hotel room without proof of marriage. It is a mother’s responsibility to find a wife for her son. Since men stay with the family after marriage, the mother looks for a hard-working, reputable, pretty girl who she would like to have around the house. The father goes with a slaughtered sheep to ask for the girl and to discuss a dowry — a camel, goat, or sheep — that his son must provide. Once an agreement is reached, a date is fixed for the wedding, which takes three months to prepare.

A wedding is a week-long communal event. The first day is for important people, the second only for women, and the third for men. The bride arrives on horseback for a henna ceremony on the final day. She arrives at her husband’s house with an egg in her hand and throws it at the door, symbolizing that she is saving her virginity for him. All have a good time with music and dancing. Chosen ahead of time, a man and a woman are stationed in front of the bridal suite to receive the bloody sheet. This custom puts great social pressure on the bride, for failure to prove virginity turns her into an outcast. The married couple stay in the house for seven days to become acquainted. Our volunteer groom’s white silk outfit included a bag and a dagger to show his manly qualities; the bride’s white lace dress had a red veil. The couple and two witnesses sat before the imam, while he wrote the contract noting the promised dowry items. After signing, the groom lifted his sword to unveil the bride, to applause by all.

Kal’at Mgouna, the “City of Roses,” was a roadside stop to sample rose and almond products, such as rose water, hand soap, and facial cream. From the mountains we descended to irrigated fields and the flat land of date palms, ending our day in Quarzazate. Formerly a French garrison, Quarzazate is Morocco’s Hollywood, with four movie studios. It sits against the snow-capped High Atlas Mountains, dominant in the distant landscape. In this oasis of dates, the fruit is harvested in October by cutting the entire stem. The yellowish brown fruit, once cut, turns brown when dry. To prepare for our trip to Marrakech, we called it an early night.

The seven-hour drive to Marrakech had several planned stops of interest. First was Ait Benhaddou, formerly a caravanserai for traders en route to Timbuktu. This citadel-like structure on the side of a mountain provided protection from the Blue Men. To reach it we crossed the river by skipping on sandbags, passing by locals on donkey back in the water. We climbed to the Agadir, a fortified granary at the top of the citadel built for secured protection. Typical of old Moroccan earth architecture, the structure is still in use for scenes from films such as Lawrence of Arabia and other classics that have been set here.

Our scenic climb of twisted roads with hairpin curves turned more spectacular with altitude, revealing purple, rust-colored, and ochre hills; almond blossoms; green river beds; flocks of sheep; wool dyed deep red; and saffron hung to dry. My ears began popping at 7000 feet. We stopped at a Berber village for lunch. Flowering rosemary plants lined the restaurant terrace, which had an area sectioned off with colorful prayer rugs. Sipping mint tea as I gazed across luminous mountains, I reflected on the Berbers’ love of beauty, and how they found inspiration in their natural surroundings.

Beyond the Tizi Pass, the green terrain of the High Atlas Mountains changed to rocky slopes. Due to desert winds the south side is barren; yet the views are arresting, with gray, red, and brown slopes; river beds; shiny black goats; and earth houses with grass-covered rooftops. Berber families live in scattered villages, some even in caves. As we moved onto flat land, orchards thickened, and satellite dishes and laundry crowded balconies. Approaching Marrakech, we passed melon fields and strawberry plants, which grow year-round. Date palms and orange trees lined the streets.

In the morning I woke up to bird sounds streaming across the terrace of my hotel room on a beautiful clear day. Following a buffet breakfast for international tourists — mostly French, English, and German — we went exploring on a horse-drawn calèche. The first stop was the Bahia Palace, residence of Ahmed Pasha — Pasha being an honorific title given by the king. Built in the late 19th century, the palace is centered on a courtyard adorned with two fountains by the harem. Inlaid wood ceilings, beautiful mosaics, and intricate plasterwork speak of past elegance. The French have introduced a fireplace. The building opens onto an Andalusian garden with flowers of harmonizing colors, scents, and tingling water. Upon the pasha’s death, his wives and concubines stripped the palace of all furnishings, leaving only the building.

A Berber pharmacy was both engaging and entertaining. We had a crash course on medicinal plants, essential oils, perfume extracts, and traditional cosmetic products. We had an opportunity to fill our shopping baskets with products for allergies, migraine headaches, snoring, and other ailments. These were followed by cosmetics — wheat germ oil for brown spots; rose, almond, and avocado oils for smooth skin; lipstick from poppies for warm lips; kohl for eyes; and various aphrodisiacs. Last but not least were the kitchen spices. Most popular was a Moroccan curry mixture of cardamom, coriander, cumin, ginger, and nutmeg.

With costumed water sellers

The Jemaa el-Fna Square in the Medina, or old quarter, is the heartbeat of Marrakech. Here open air storytellers, snake charmers, and witch doctors ply their trade. UNESCO has designated this as a site to preserve the “oral heritage of humanity.” I walked among fortune tellers with tarot cards and beads under umbrellas for the privacy of their customers. Enraptured audiences three-deep circled storytellers. Plastic body parts identified herbal medicines for the right cure. Costumed water sellers posed for photos. Itinerant musicians and orange juice and nut merchants contributed to the amazing buzz.

At sunset the tumult of activity grew denser as the square filled up with makeshift restaurants. We returned there to experience the nighttime scene and have dinner. Each food stand, identified by a number, displayed its menu in both Arabic and French. The aromas from the stalls mixed with billowing smoke from the braziers. We settled at one stand and feasted on grilled chicken, beef kebabs, and seafood with various accompanying dishes. Then we walked over to an ice cream shop known for its exotic flavors, such as apple, avocado, and fig, along with more familiar ones. As I walked back with my cone of avocado ice cream in hand, I had to make my way through knots of onlookers of acrobats, belly dancers, magicians, and henna tattooers — an open-air theater indeed, with hundreds of high-energy performers lit by kerosene lanterns.

Islamic Art Museum

The next day we were free to explore on our own. Several of us rode a calèche to the Islamic Art Museum and the Majorelle Garden. Louis Majorelle, a French painter who settled in Marrakech in 1924, became one of the major plant collectors of his time. The garden has an abundance of vegetal shapes and forms from five continents. Palms, cactus, bamboo, and other exotic plants line the pathways; water lilies, lotus, papyrus, and other aquatic plants grow in the reflecting pools. All the garden structures are painted in vivid blue. Yves Saint Laurent has acquired the property and established a trust to ensure the garden’s future. The painting studio now houses a Museum of Islamic Art, with needlework and earthenware from various parts of Morocco.

Lunch was another unique experience. We had mechoui — roast lamb brushed with butter and hung on a hook inside a covered pit oven to cook slowly. The meat comes out slightly pink with cracker-crisp skin. After tearing off the meat, we dipped it in salt and cumin, then placed it between slices of fresh bread. My self-discipline against red meat fell apart in the face of such tasty dishes.

Some of us took narrow, winding streets to the Dar Si Said Museum, former palace of the son of the family who ruled Marrakech at the dawn of the 20th century. The museum provides insight into the daily lives of the Berbers, founders of the city. In addition to collections of copper and pottery, there are displays of Atlas carpets, jewelry, clothing, bath tools, and culinary objects. Also of interest are musical instruments, rustic furniture covered with symbols, and fairground swings used at festivals until the 1940s. Upstairs is a replica of a bridal chamber.

There was a farewell dinner for those who had opted out of the trip extension to Marrakech. On the way we stopped at a bookstore to acquire cookbooks. Dinner was an occasion for another feast; this time the restaurant, the Red House, was a former palace. Following a welcome drink in the ornate receiving room, we were served a four-course meal. The most noteworthy aspect was the multiple desserts we enjoyed, including a birthday cake delivered for a fellow traveler by the inhouse belly dancer. The merriment convinced me to go to some exotic country for my own birthday.

Our four-night post-trip extension was an opportunity to explore the radius of Marrakech. We began with an excursion to the Cascades d’Ouzoud, waterfalls 140 kilometers north of the city. A stop on market day in Allattolia revealed new sights. Men sitting at a row of sewing machines made alterations while people shopped; peddlers sold old clothing and shoes; donkeys were branded; colorful spices sat on the ground in conical mounds, their pungent smells mixing with the aromas of stewing chickpeas and fava beans. We were amazed at the troubling yet fascinating poverty; the locals stared back with equal curiosity.

Dropping 300 feet in three streams, the waterfalls created a rainbow in the misty air. I descended to the bottom on a narrow path, stopping at different observation areas. Barbary apes that make this moist environment their home enhanced the landscape.

The Marrakech souk is a labyrinth of alleys crammed with small shops selling textiles, carpets, clothing, shoes, slippers, leather bags, brassware, woodcrafts, antique doors, and much more. One store, called Les Perles du Sud (Pearls of the South) carried the best chunky jewelry I had seen. Glass cases displayed one-of-a-kind silver and semiprecious stone Berber earrings, bracelets, and necklaces. The amber, coral, lapis, and turquoise were all stunning. By now I was able to discern differences between more refined Arab designs and Berber ones, which are closer to African motifs. I bought two shirts, one of each kind. However, my favorite purchase of all was a decorative, multicolored, mirrored leather piece made for a camel.

Marrakech is a city of beautiful gardens, which provide shade in a place known for its summer heat, which can reach 125°F. The Hotel Mamounia, a former palace, has immaculate gardens, with an alley of olive trees and flowering shrubs punctuating its formal landscape. Inside I loved a fountain with rose petals floating in its marble tub. Giulin is an upscale neighborhood, where we enjoyed a French meal at a restaurant called La Jacaranda.

Our final excursion was to Amizmiz in the mountains south of Marrakech. We climbed by van, passing Berber villages, terraced wheat fields, almond trees with white blossoms, and peach trees with pink blossoms, until we were at eye level with the snowy peaks of the High Atlas. The highest peak is Toubkal at 13,668 feet, Africa’s second highest after Kilimanjaro at 18,000 feet. We transferred to mules to negotiate the rocky, muddy, up-and-down mountain trails leading to the former Jewish settlement of Mole Ouraze. Jews lived here to mine the salt quarries of the High Atlas. Complete with a synagogue, the abandoned complex is maintained by mountain Berbers, who are paid by city Jews as caretakers.

Couscous with chicken

and vegetables

A farming Berber family hosted us for lunch, where we learned about baking bread in a tandour by sticking flat dough to the inner wall of an oven. Sitting on floor cushions across from a family portrait of the king with his newborn heir, we enjoyed couscous with chicken and vegetables, as well as beef tajine. While women cleaned up, the male head of the household and his son showed us around. Our host had built the two-story house himself using cedar and cane for the ceilings. The wood came from the surrounding forest. Everybody in this village, including my mule driver, spoke French.

On the final day of our tour we had a home-hosted meal of a very different sort. We were guests at the villa of a well-to-do developer, who had also built his own house by relying on top-of-the-line craftsmen for the marble floors and carved detail of the interior. We left our shoes at the door. The family of four with two young daughters, aged four and two, had domestic help. What distinguished this house from others we had seen was its all-Arab decor devoid of any Berber aesthetic, including the rugs. The entire meal, prepared by our hostess, was both a culinary and a visual feast, like most Moroccan meals.

Visiting Morocco was a delightful discovery. It is a country blessed with diversity of nature, stunning landscapes, and a fascinating mixture of cultures, intoxicating aromas, beauty, and friendship. It is also a young country, with 70% of the population under 27 and a high unemployment rate. As it conquers illiteracy and poverty, I am optimistic that Morocco will retain its unique character, which makes it such a compelling travel destination.

Enjoying local transportation

← Morocco (main page)

&nb