March 2006

As I walked down the aisle to my seat on Royal Air Maroc, incense permeated the air. Some of the passengers were in flamboyant African dress, others in modest Arab garb. I settled next to a Moroccan from Brooklyn, who was going home to visit his sick father. Over the nine hours of our trip, one of which was spent on the ground waiting for clearance, he talked about growing up in Morocco. His story, as engaging as a good book, was steeped in the colors, flavors, and people of his country. One of eight children, all of whom had dispersed throughout the world to earn a living, he had gone to school in France, then in Canada, and finally settled in the United States with a green card. He managed the restaurant of a hotel that catered to Jewish families in Brooklyn.

As we cleared customs in Casablanca our trip leader, Aziz, met our group of nine who had signed up for a pre-trip to Essaouira, an ancient walled city on the Atlantic coast. Dressed in a black skullcap and brown jalaba, the traditional long garb worn by Moroccan men and women, he welcomed us to our “second home,” informing us that Morocco had been the first country to recognize the United States after the Civil War. On the way to our hotel we passed red flags with green stars — red symbolizing the bloodshed for independence from France in 1956, and the five-pointed star the five “pillars” of Islam.

Casablanca, a bustling, modern port with a population of 5 million, is Africa’s second largest city after Cairo. It is the industrial center of Morocco, where 70% of the country’s industry is located. It is on the same latitude as California and enjoys a similar climate. 80% of the city’s power is hydroelectric; the remainder is generated by coal. People drive mostly diesel or small French cars, due to the high cost of gasoline — $12 a gallon. All taxis are old Mercedes, referred to by the people as “German camels.”

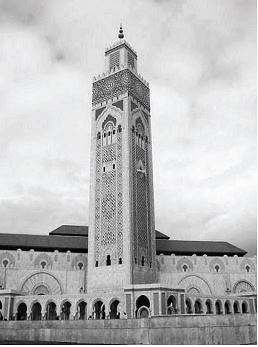

Our main excursion was to the Hassan II Mosque, the largest religious monument in the world after Mecca. Inspired by a Koranic verse which says “The Throne of God was on water,” the late Hassan II had the structure partly erected on water. This grand 20th‑century edifice, built by public donations, sits at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, its 200-meter-high minaret visible from all corners of the city. The prayer hall, which holds 25,000, has a movable roof accommodating 100,000 worshipers when raised. Two hanging mezzanines with fine carvings are reserved for women. The ablution hall, with its 41 fountains, and the two tiled baths are jewels of Arab-Islamic architecture.

Hasan II Mosque

The boardwalk in Casablanca is called “La Corniche,” reflecting the dominant role of the French language in Moroccan public life. We strolled along the boardwalk, which was lined with teahouses, fish restaurants, and even a MacDonald’s. The Sunday family promenade blended modest Arab elegance with African flair, as women in jalabas of somber tones walked about sporting headscarves in bright blue, lime green, or saffron. Those with dark head covers wore lavender or pink jalabas, delightful to the unaccustomed eye.

The white cityscape gives Casablanca its unique character. True to the city’s name, which means “white house” in Portuguese, all houses are painted white. City Hall Square is a major gathering place, where people congregate to socialize and watch the fountain light up. To reach the square, one has to scramble across a wide boulevard through heavy traffic, which does not stop for pedestrians.

Our first meal in the hotel was one of many memorable culinary experiences we had throughout the trip. At the center the table featured the customary dates with lemon, followed by harira, a thick, spiced soup made of lentils and chickpeas. The main course was tajine of beef braised with prunes and onions and served with a hard-boiled egg on the side. We mopped up the juices with chunks torn from freshly baked round loaves of khobra bread. The meal concluded with thinly sliced oranges sprinkled with rose water and cinnamon.

The next morning we traveled 340 kilometers south, taking the scenic route along the coast to Essaouira. Small orange, yellow, and purple flowers on the way turned to freshly plowed fields separated by serpentine walls of field rocks or cacti, with flocks of sheep and cows grazing in lush green pastures which ended at the shoreline. We stopped by the roadside to watch men unload a truckload of mud-covered carrots into a pool of water, agitating it with their feet to wash off the mud. Women carried big bundles of brush for firewood on their heads. Men rode donkey-drawn carts, as young men with fishing rods sped by.

Morocco’s Atlantic coast is dotted with resorts; however, it was still early for the summer buzz. We stopped at a seafood restaurant for lunch. As soon as a platter of fresh oysters and sea urchins arrived as an appetizer, we all reached for our cameras to document this incredible display. Since eating a sea urchin was a new experience for me, I had to learn how to scoop out its roe. The main course was fried sardines, flounder, and red snapper, followed by orange tart with the rind intact.

Berber herders waved to us as we resumed our trip. Children came running to earn a few dirhams by posing for photos. We drove by plastic-covered greenhouses, surf breaking on the shore, and tombs scattered in fields. When we reached Safi, a coastal town whose major industries are phosphate and sardines, the landscape changed to earth-toned houses with brightly colored doors and window frames. Flat roofs featured green tiles and slender chimneys. The weather felt much warmer as blooming mimosa and hibiscus trees came into view. We stopped outside the main gate of the Essaouira medina, the walled medieval city, as vehicles cannot negotiate its narrow streets. Porters unloaded our luggage onto two-wheeled carts, which they pulled by hand through the narrow streets to our hotel. Its massive gate did not reveal what lay beyond.

Three stories of balconies encircled a luxuriant interior patio with a central fountain under a skylight. On the first floor a library and sitting nooks, carpeted with straw mats supporting low mosaic tables on wrought iron stands, opened onto the patio. Moroccan crafts adorned the walls. Our morning began here with fresh-squeezed orange juice, crepes with honey, croissants, and coffee.

Essaouira

A fascinating harbor walk took us past fishing boats, fishermen mending nets, and seagulls perched on seawalls. We stopped at the wholesale fish market and watched fish, including eels, being auctioned to retailers. For lunch we bought our own fish by the kilo and had it grilled at one of the roadside restaurants. We enjoyed shrimp, two kinds of squid, and sea bass, accompanied by a salad of tomatoes and onions, along with freshly baked bread. We ate with our hands like the locals.

After lunch we visited the Argan Oil Cooperative, which benefits poor women. The argan tree, native to Morocco, is similar to an olive tree. Goats eat the fruit; the pits are used to process oil for cosmetic or medicinal purposes. By hand women skin the fruit, crack the nuts, roast the seeds, and then squeeze them to extract the oil. The pits are either roasted or cold-pressed, depending on the intended product. After sampling tasty almond paste mixed with oil and honey, we bought some, in addition to salad oil and soap.

In the afternoon we walked the narrow alleys of the Medina, the walled city center, which has different sections — a mosque, a medresa (religious school), a fountain, a hamam (public bath), and baking ovens. Women make bread at home, inscribe the family name into the bottom of a loaf, and send it out for baking. The aroma of fresh-baked bread on the streets reminded me of my childhood in Turkey. Many women still go to a hamam for the day, to socialize and to look for suitable brides for their sons.

Thuya wood is unique to Morocco; Essaouira is renowned for this woodcraft. Thuya is a dark, deeply knotted wood. Often it is combined with lemon wood or ebony. During our visit to an artisans’ cooperative, we watched men trace designs on wood, cut around the stencils, and fill them in with lighter-colored wood or mother-of-pearl. I liked the rich grain of the wood, so many of my Moroccan souvenirs are from solid thuya.

A sunset over the Atlantic was the highlight of our day. I sat on a wall near the ocean, watching the blue sky shift into streaks of orange, red, yellow, pink, and deep purple. The vast canvas of color formed a backdrop to flying seagulls that seemed to be rushing home to beat the night. I took many photos until the sun disappeared behind the horizon.

Market day is a big day for locals. We traveled south to observe the Wednesday market, where donkeys and sheep were on sale. Sheep were slaughtered on the spot and carried home in deep baskets secured to donkeys. Children accompanied parents to load up the donkeys. The produce section of the market was a chaotic display of tomatoes, turnips, carrots, onions, potatoes, oranges, and spices, all spread over sheets of plastic on the ground. Other items for sale were bolts of fabric, shoes made of recycled tires, clay pots, and decorated ceramic urns. Men had shaves and haircuts in tented barbershops, while donkeys were fitted to be shod. An arbitration court of elders settled disputes between merchants.

A visit to an argan grove to watch goats feeding was delightful. Big and little goats stood on their hind legs to reach the fruit and climbed the branches to reach fruit higher up. Easy to spot in their shaggy brown, white, and black hair, they allowed me to approach and take pictures as they continued eating. They seemed accustomed to being photographed, as they appear on many postcards. Afterwards by the beach, we enjoyed shish kebab cooked over a charcoal brazier and seasoned with cumin.

Following three days in picturesque Essaouira, with its orange trees, whitewashed buildings with blue doors, horse-drawn carts, and panorama of beaches, we headed back to Casablanca via an alternate route through the countryside. As we entered the city, the languid character of the south gave way to pollution and noise. Women’s attire ranged from the tightest jeans and stiletto shoes to long coats and jalabas. Aziz suggested we check out Rick’s bar at the Hyatt Hotel, also advising us, when crossing the street, just to begin walking, thus forcing traffic to stop. The bar, an imitation of the one in the movie Casablanca, featured a piano and pictures of Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman.

In the morning we traded our van for a bus to accommodate our full group of sixteen. Before leaving for the main tour, which started in Rabat, we visited an indoor market. Small butcher shops featured signs in French, each identifying the kind of meat sold — horse, beef, or chicken. Others sold live turtles, snails, and fish, or exotic produce such as truffles, kumquats, and small bananas. The variety of dates and the assortment of green, black, and red olives were picture-book displays.

In Rabat our day began with an Arabic lesson from Aziz, who went over basic words phonetically, teaching us how to greet and thank. A common greeting is “Salaam aleikum,” meaning “Peace be upon you,” accompanied by multiple kisses on each cheek as people meet one another on the street. “Shukran,” indicating gratitude, we used profusely for the warm hospitality extended to us everywhere.

Rabat, an imperial city founded by the Berbers, is the capital of Morocco, a constitutional monarchy. The King rules over a nation of 32 million, 60% of whom are Berbers. 97% of the population is Muslim, following a tolerant Sunni tradition. They are represented by a parliament of 555 members elected from among 25 parties every 6 years. The Paris-educated, 43-year-old King, Mohamed VI, married Princess Lalla Salma from Fez in 2002. The heir to the throne, Moulay Hassan, was born in 2003.

Keyhole gates

at Royal Palace

The 18th-century Royal Palace is one of a dozen palaces in the country where the king holds ceremonies of allegiance. Our experience was of its facade. Featuring seven keyhole gates, which represent heaven, the palace employs 2000 workers. Their ranks are indicated by the color of uniforms, with gray for the major armed guards, blue for police, and red for ceremonial workers, whose Turkish-imported costumes date back to the Ottoman Empire. The dark-skinned royal servants in white jalabas are Africans, whose jobs are inherited. The palace has its own necropolis, as well as a mosque for the king, who rides his horse to the Friday midday service.

Stork nest on

Roman column

Set in the wild gardens of Chellah are hauntingly beautiful ancient Roman ruins within 14th-century walls from the third Berber dynasty, the Merinids. Storks come to spend the winter here, nesting on top of tall trees and ruins to tend to their offspring. Mesmerized by the tropical setting, I walked among loquat, orange, and grapefruit trees; wandered through the Roman agora; and photographed Islamic tombs and white storks on crumbling walls. Shaded by a banana tree is a small fountain with coins in the center of a pool. Women come to bathe with eels living in depths so as to grant fertility.

Hassan II Tower and Roman columns

The Hassan II Tower is a 12th-century Islamic masterpiece with four differently carved facades. It is all that remains of the world’s biggest planned mosque, which was never finished because of the Sultan’s death. The 312 Roman columns at the base once supported an immense roof, destroyed by an earthquake in 1755. Opposite is the marble mausoleum of King Hassan’s father, Mohammad V, who led Morocco to independence. The interior of the structure, designed by Vietnamese architect Vo Toan, is a showpiece of craftsmanship.

Rabat is situated on the left side of the river Sale, opposite the town named after the salty river. Fishermen throw nets for sardines, which people buy off boats. Naturally, lunch was fish soup and grilled sardines. Afterwards we walked in the Andalusian Gardens, within the walls of the Kasbah of the Udayas. The repetitive palm motif on the main gate is meant to soothe the eye into contemplation. The riyadh (garden) of the kasbah (fortified city) is designed to bring harmony like the heavens. Bird and water sounds complement one another, as do the colors of flowers. People meditate here among the fragrant chaos of flowers and citrus trees.

Following a visit to the Museum of Archeology — where we viewed Neolithic skeletons, Roman treasures, ceramics, coins, and Islamic tombstones — we went to the supermarket to stock up for our camping adventure in the Sahara. I couldn’t resist buying typical Moroccan plates at $2 apiece. Later on at our hotel we were given a lecture on the status of women by a woman named Emina, who worked for US AID’s Democracy Project.

Before independence, women wore traditional dress and always had to be accompanied by men. As of 1957 traditions began changing. In 1999 bills to abolish polygamy and to allow divorce were put to Parliament, but rejected. In October 2003 the new family law passed, changing the legal age of marriage to eighteen. Civil and religious marriages coexist; however, divorce cases must be heard in court, where women’s rights are recognized in the splitting of assets. Honor killing and female circumcision are illegal.

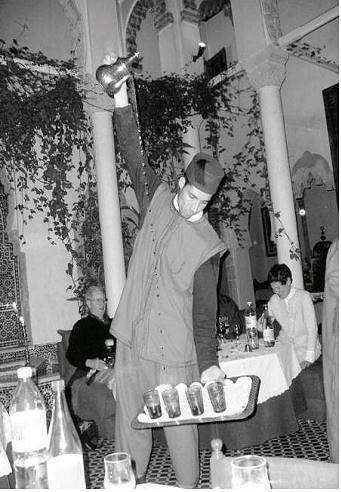

Tea ritual

Our Welcome Dinner at Dinarjet, an upscale restaurant in the Medina, was unrivaled. This beautifully tiled restaurant was formerly the home of a wealthy man. At table we washed our hands over a brass bowl and dried them on heated towels. Our four-course meal started with pastilla (squab pie), followed by various dishes — eggplant, beets, spinach, fava beans, tomatoes with cucumbers, and briwat (fried pastry). Tajines of lamb with raisins, beef, and chicken with olives came as the main course. Dessert was jawhara — baked flaky pastry leaves layered with cream, flavored with rose water, and topped with powdered sugar. Then we enjoyed mint tea and ritual sprinkling of rose water on our hands. Arabic music on instruments such as the oud, bendir, and kanun accompanied our dinner.

Our drive to Meknes, both scenic and educational, was through the countryside with stops. Morocco is the world’s fourth largest exporter of cork, which is harvested by peeling the bark of a cork tree every seven years over a period of 90 years. Afterwards the tree is used for firewood. The town of Tiflet is a new Berber settlement with many buildings, mostly vacant homes of laborers, who have left to join the 3 million Moroccan immigrants in France. The government discourages nomadic life in order to improve literacy, establishing new towns with schools and hospitals. The illiteracy rate has dropped from 70% to 40% for men, and 50% for women.

Agriculture constitutes 55% of Morocco’s economy, so some two-thirds of the land depends on rainfall. Due to global warming, drought is an increasing concern. There is underground water good for growing truffles, but even that has been receding because of drought. Truffles are harvested with the aid of digging dogs. Since this is a labor-intensive process, truffles sell for $15 a kilo. All agriculture is supposed to be organic; the only fertilizer used is phosphate. Vineyards of white Muscat grapes growing close to the ground line the road to Khemisset. Introduced by the French, the wine industry thrives in Morocco. Since wine is a source of revenue, the Islamic prohibition on alcohol is not enforced.

There is a fertile valley of olive groves en route to Meknes, an imperial city built in the 17th century that takes its name from a Berber tribe. Beating the trees with a stick brings down the olives. The season of harvesting determines the color of the olives — green in mid-November, brown in late November, and black in mid-December. Farmers keep one fifth of the crops they grow, which include barley and wheat. As we began climbing the foothills of the Atlas Mountains, roadside vendors appeared selling butter, honey, olive oil, and free-range eggs, which we bought for our campsite. Sheepdogs also appeared, expecting to be fed; they are jobless because all wolves have been killed.

Sultan Moulay Ismail built massive walls around Meknes in addition to 52 palaces, stables, and granaries, using white slave labor from Europe to serve his all-black army. These old buildings are now used as schools and hospitals. The Jews immigrated to Israel in the 1960s or have moved to modern cities like Casablanca, leaving the historic quarter behind. The bustling market pays tribute to Morocco’s two sacred foods, dates and olives. On display were close to 30 kinds of dates and heaps of olives in every imaginable form. Some were whole, some cut up in circles, and some in chunks alternating with mounds of lemons. The seedless tangerines at the market were the sweetest I had ever tasted.

Damasquines, metal worked with silver, is the primary craft of Meknes, the only city where the craft exists outside of Toledo in Spain and its city of origin, Damascus. We watched artisans apply silver designs to brass creating ornaments, vases, bowls, and trays. I bought a hand of Fatima — a wall ornament for the home to ward off the evil eye. Then over a two‑hour lunch we enjoyed grilled meats on a bed of pilaf laced with red peppers, preceded by warm and cold vegetable dishes and accompanied by a basketful of round loaves of bread. The platter of fragrant bananas, oranges, and strawberries that followed tasted like they had just been picked. Savoring a semolina biscuit with mint tea, we resumed our journey.

Traveling north we reached the site of Volubilis, whose name means “morning glory” and which was the region’s first Roman city. Leveled by an earthquake in 1755, the location has been designated a World Heritage Site. Amidst asphodels lie impressive mosaics and ruins of an aqueduct, an agora, an arch of triumph, and several columns of houses now serving as posts for nesting storks. To continue to Fez we turned southward, driving through the holy city of Moulay Idriss. Named after its founder, who is believed to have been a descendant of the Prophet Mohammad, this was Morocco’s first Arab town. Its whitewashed vistas overlook rolling hills dotted with grazing goats. The road continues along green fields of various shades, depending on the crops grown in each.

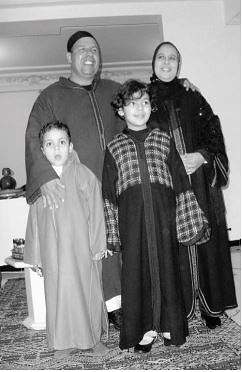

Aziz with family

Founded in the late 8th century as the first imperial city, Fez is Morocco’s intellectual capital, home to its oldest university and royal palace. Aziz, proud to show us his home town, invited us to meet his family right away. He lived with his wife, a high school Arabic teacher, and two children, nine and six, in a two-bedroom apartment. Furnished traditionally, the living room, with cushioned seats on the perimeters, opened onto the dining room. Coffee tables inlaid with mother of pearl sat near a mirrored Berber rug. We enjoyed mint tea accompanied by homemade sweets and crepes, and joined in the birthday celebration of Aziz’s daughter with frosted chocolate cake.

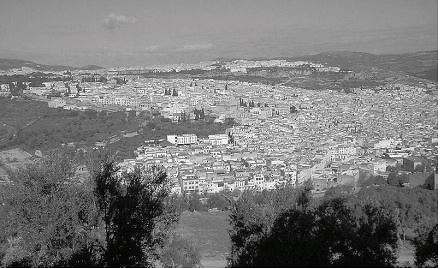

The next day began with a panoramic hilltop view of the city, both parts of which are joined by a bridge over the River Fez. We visited the Royal Palace and explored the Mellah, the old quarter, before plunging into the Fez Medina, the most well preserved medieval city in the world. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Medina is made up of four quarters and many subquarters, housing 500,000 people within an area of 64 square miles. Entered through nine gates, it is a maze of 9000 crowded alleyways with 850 cul-de-sacs and 600 craft shops. There are 300 mosques. One of the most often-heard words is “Balek!” — “Watch out!” — as loaded donkeys come through the alleys.

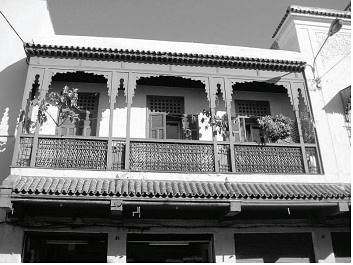

Traditional Fez architecture

The medresa we visited housed university students studying theology. Their seven-year coursework requires rote learning of the Koran. Students live in very close quarters just big enough for two to sleep on bunks. We chatted with a couple of Berber students, who appeared happy with their lives compared to home.

Fez is known for its unique blue ceramics, made of gray clay. At the ceramic shop we watched potters at wheels, kilns fueled by olive pits, and women glazing pots. Artisans made tables by cutting and chiseling mosaic tiles into small shapes and arranging them into designs as they placed them face down, then pouring cement to hold the pieces when hardened. Beautifully finished square, round, and crescent-shaped tables of various sizes and on wrought iron legs of different heights beckoned potential buyers.

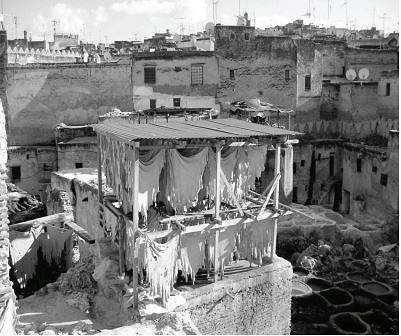

Tannery

Following a visit to a carpet cooperative, where we saw both antique and new Berber and Fez rugs, we went to a tannery. Munching fresh bread, we picked up sprigs of mint to counter the odor. Overlooking huge vats, we watched as goat, sheep, and camel skins were soaked in lime, treated with pigeon droppings as men agitated the solution standing knee-deep in rubber boots, and finally hung to dry. At the end of the day we had seen only a fourth of the Medina.

In the evening we split into groups for a home-hosted meal. Four of us rode in our host’s VW to the complex where he had a two-bedroom apartment. We met his wife and three children, a boy and two girls aged two to eleven. Our hostess, in traditional garb with headscarf, offered us mint tea in the living room, while the oldest child, the son, finished his homework with assistance from his father at the computer. Then we gathered around a low table for a meal of harira (thick vegetable soup), padiljan (eggplant), and tajine of chicken, which we tore up with our fingers from a centrally placed platter. Eating in this fashion minimizes the number of dirty dishes, and makes it easy to clean up by shaking out the plastic tablecloth cover.

Our host worked as an inspector of Arabic teaching at junior high and high school levels — a job which required traveling. His wife stayed home with the two-year-old; the older two attended third and sixth grade at a private school. The parents preferred private education because of small classes and early instruction in French and English, which does not start until high school in public schools. Tuition is $150 a month per child, plus transport. Children are in school from 8 to 12:30 and again from 2 to 6 pm. They come home for lunch. Our enjoyable visit ended with a viewing of framed wedding pictures in the bedroom of this home, otherwise devoid of any wall decor.

On the way out of town the next morning, we drove through a street lined with trees in bloom with purple flowers to an upper class residential area of Fez. With villas on both sides of the street, we were able to see another face of Fez outside the Medina.

On the Middle Atlas Mountain route, our first stop was Ifrane, a ski resort, called the Switzerland of Morocco. Here people fish for trout and hunt for red-legged hare. The king comes here to ski. The town boasts a sculpture of the last lion, killed by the French. It was a sunny clear day with snow on the ground and aspen trees all around. Having recently left winter behind, I did not think I would get excited over snow, but I did. It was so beautiful that I took several pictures.

As we continued climbing my ears began to pop. We drove past giant cedar forests. The government regulates the cutting of cedar, which is popular for cabinet making. Snowy veins melted into little lakes; troughs channeled water into fields; whims of geology covered the hillsides and valley slopes with pink and green rocks and rich purple soil. After we crossed a 6000-foot pass in the Atlas Mountains, which divide Morocco into east and west, the landscape shifted to stony land with stubby greenery, and the earth turned red and ochre. Villages of mud houses and square minarets signaled Berber settlements.

The mountains are Berber land, with three different settlement areas and dialects. Those living along the Rif Mountains are the Masbada, including the Tuareg tribe known as the Blue Men, who used to attack caravans. They speak Tarifite. The Middle Atlas tribes are the Znatu, who have come from Algeria and speak Tachelit. The Senhaja of the High Atlas speak Tamarzit, the Berber dialect spoken throughout the country. Date palms with a life span of 200 years grow at lower altitudes and are harvested by “date Berbers.” The palms have surface roots, pollinate naturally, and bear fruit which ripens in six months. There are 120 kinds of dates among Morocco’s 4 million palms.

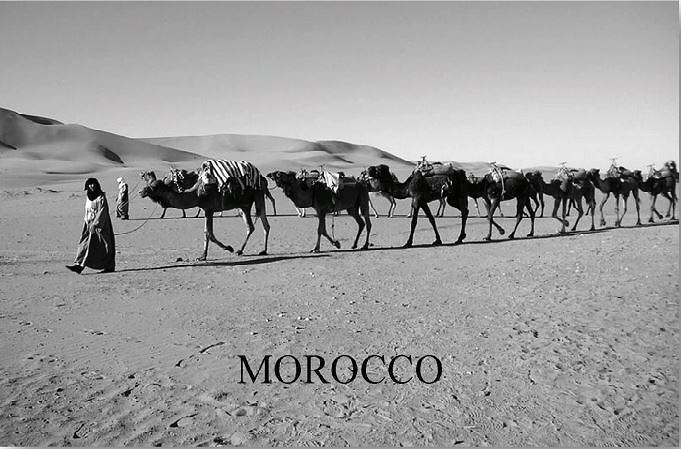

The nomadic Berbers judge their wealth by the number of camels they own. These are one-humped camels with a life expectancy of 46 years. They have an eighteen-month gestation period, and their skin becomes lighter with age. A white camel is old, which was a revelation to me, since I thought the one I had ridden in Egypt was of a different breed. A camel has a body temperature of 107º F; its hooves adjust to different terrains. It can carry twice the load of a mule. All camels belong to someone; none are wild.

On the way we stopped for lunch in Midelt at the Kasbah Asma, the former palace of a ruling family, as opposed to a ksar douar, a dwelling of extended families, such as the one we visited later in Rissani. By now the five layers of clothing I had started out with were down to two. As we headed toward the Sahara, taking in spectacular views of the Ziz Gorges and the Ziz Valley, the air temperature became a function of the sun. When the sun was out it was hot; otherwise it was cold. The landscape turned to monochromatic shades of brown, dotted with oases of date palms along riverbeds of clear water.

← China