March 2010

After an enjoyable week in Myanmar, we returned to Bangkok and connected with the nine other people in our group to begin the main trip. Our first destination was Laos. Our flight out of Bangkok was delayed by two hours, while we waited for the smoke from burning fields to clear in Luang Prabang. As we had experienced a similar delay in Myanmar, it became clear that burning farmland before the monsoon season was a routine practice in the region.

The entire city of Luang Prabang, the former royal capital of Laos, has been designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, which has also described it as “the best preserved city in Southeast Asia.” It is located on a peninsula at the confluence of the Mekong and Khan Rivers, with lush green mountains all around. To reach the old town, we transferred from the bus to tuk-tuks (auto rickshaws), which can negotiate the narrow roads in the heart of the city, to the Maison Dala Bua, our hotel for two nights on the Mekong River. Befitting its name, which means “Lotus Princess,” the classical oriental-style fifteen-room hotel had a lotus pond with ducks and was set amidst tropical gardens, offering a sharp contrast to the tumult we had just left behind in Bangkok.

Our afternoon tour of Luang Prabang took us through narrow lanes by aging 19th-century French colonial villas mixed in with worn Laotian-style timber houses and temples. Time seemed to have stopped in the city, due to its isolation under Communist control. Luang Prabang was established six centuries before the Communists abolished the monarchy in 1975, imprisoning the royal family in a remote reeducation camp and setting up their own government in what had long been the capital city.

The Royal Palace Museum offered us an insight into the history of the region. The palace was constructed by the French from 1904 to 1909 as a residential gift to King Sisavang Vong, as Laos had been part of French Indochina since the late 19th century. Cruciform in layout and mounted on a multi-tier platform, the structure exhibits a mixture of classical Laotian and French beaux arts styles. The ground floor has several halls displaying diplomatic gifts to the Laotian kings, a collection of regalia, many gilded Buddha statues, and artistic treasures. The prize piece in the museum is the famed gold Khmer Pha Bang Buddha.

Temple architecture

with sweeping roofs

The royal temple or Wat Xieng Thong (Golden City Monastery), built in 1513, is the oldest in the city and was patronized by the monarchy until 1975. It has low sweeping roofs in the classical Luang Prabang style of temple architecture. Its eight thick supporting pillars, richly stenciled in gold, guide the eye to golden Buddha images in the back. Outside in the rear is an elaborate mosaic of the Tree of Life set against a deep red background. The combination of gold and deep red gives this temple a regal aura.

In the center of the old town rises Mount Phu Si, a nearly sheer rock with steep wooded slopes. We climbed 328 winding steps to the 79-foot-high summit, site of the That Chom Si shrine, which has an impressive gilded stupa in classical Laotian form. The summit also offers views of the surrounding mountains, the city, and the rivers below. Finding a spot among tourists sprawled along the stepped walls of the shrine, we were rewarded for our climb by a sunset.

The next day we woke to the crowing of roosters, and left the hotel at 6 am to participate in the ancient Buddhist ritual of giving alms to monks. We took our place next to locals with food offerings sitting on straw mats on the sidewalk of one of the city streets. We shaped sticky rice into balls, which we kept warm in individual bamboo baskets. Hundreds of orange-robed monks from nearby temples paraded before us in single file, from oldest to youngest, to receive our offerings in return for their prayers. The sense of calm and solemnity introduced by the monks continued in the temples we visited during the day. Despite the efforts of the Communist government to wipe out religion from Laotian life, faith remains a dominant force as children grow up giving alms, going to temples, and sustaining all Buddhist traditions.

On the way back we walked through the amazing sights and smells of the Morning Market. Customers were beckoned by a variety of meat smoking over charcoal fires, eggs boiling in cauldrons, insects sizzling in frying pans, and heaps of ants’ eggs mixed with rice. Spring rolls wrapped in freshly made rice paper and food to go packaged in banana leaves were popular choices for those on their way to work.

Returning to the hotel for a less exotic breakfast, we enjoyed a fresh fruit platter of watermelon, papaya, mango, and banana, along with warm French baguettes, butter, jam, and eggs cooked to order. Despite the smoky skies and smells wafting from burning fields, the languid pace of our setting provided a fluid sense of calm, which continued during our cruise on the Mekong River.

The Mekong, whose name means “Mother of Rivers,” is the world’s tenth longest river. It begins in Tibet and goes through China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia. It supports 90 million people, who produce 54,000 square miles of rice every year. Home to many species of giant fish, the river is the inspiration behind the phaya naga, or Mekong dragons, which guard palaces and grace rooflines.

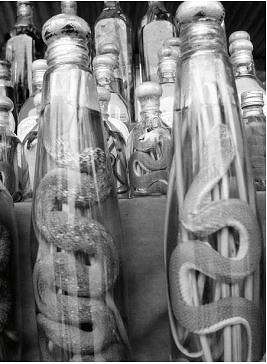

Rice wine with snakes

To reach the dock for our cruise, we walked through Ban Xang Hai (“Jar Maker Village”), named after the village’s former main industry. Jars still abound, but they are now made elsewhere. The village now devotes itself to silk weaving and to producing lao-lao, a moonshine rice wine. Women at traditional looms wove silk fabrics, displayed at stalls lining both sides of the road, while little children played underfoot or nearby. Though a silk shawl and a tribal silver necklace were irresistible purchases, I kept my distance from the rice drink in bottles, some with a snake curled up in them as an elixir. I watched men boil and pack rice in earthenware jars to ferment for a week. The liquid is then drained and bottled. This wine has an alcohol content of 15%.

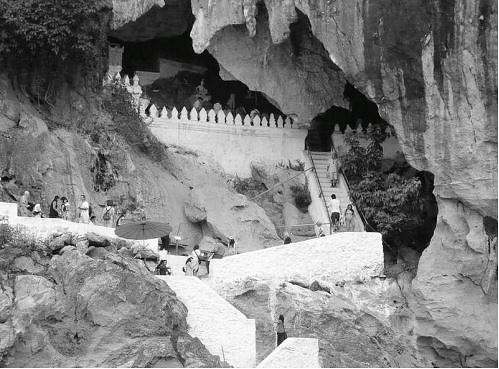

Pak Ou Caves

A two-hour boat excursion up river took us to the Pak Ou Caves, set in the side of a limestone cliff near the confluence of the Mekong and Nam Ou Rivers. These caves, discovered in the 16th century, have been venerated ever since. They are filled with Buddha statues of all sorts and sizes, placed onto rock shelves and crammed into crevices by the faithful as offerings to the river spirits to ensure a safe journey, in a melding of superstition and faith. The lower of the two caves is easily accessible from the river, though we had to jump from boat to boat five times to step ashore. The upper cave may be reached by steep steps cut into cliffs and is deeper, requiring a flashlight for exploration. High above the water by the mouth of the cave are marks indicating water levels from monsoons in different years. A sheltered area between the two caves provides a pleasant spot for a picnic lunch.

Lunch for us was on the boat, prepared by the crew. Over lunch we continued our learning and discovery. Ole, our Laotian guide, explained that the government had controlled all land and business and discouraged the practice of any religion during the first ten years after the Communist takeover in 1975. Later, land was given back to people and private ownership allowed. A majority of people are practicing Buddhists; Christianity and other religions are tolerated as long as there is no proselytizing.

Education is free at all levels; parents pay for books and uniforms. Poor farming families turn to monasteries to benefit from free education and to protect their children from becoming involved in the lucrative drug trade. Children cut off all ties with parents when they attend school to become monks. Until the age of 20 they are novices and wear robes covering only one shoulder. When they are eligible to become full monks, they commit to the various stages of monkhood and do not leave the monastery unless they wish to renounce monastic life. Regular schools are in session from September through May; students are on vacation for three months during the monsoon season.

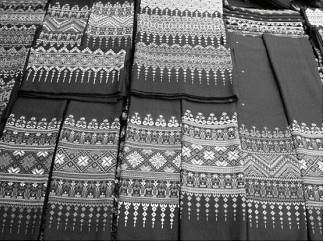

Silk shawls at

the Night Market

Idling past the stalls of the Night Market offered a feast for the eye. People from the Hmong tribes trek down the mountains to sell their hand-loomed indigo and sophisticated patchwork fabrics, along with other special crafts at this market. Treasures I picked up here were bags of various sizes with hand-embroidered motifs, a cushion cover with a reverse appliqué pattern, and a multicolor patchwork quilt. All my purchases were made in US dollars, accepted throughout the country.

Dinner on our final night in Luang Prabang was at the Boulevard Restaurant near the Night Market. Cucumber soup with pork preceded a spread of sweet-and-sour pork, chicken with cashews, vegetables, rice, and morning glory salad, all followed by a fruit plate of sliced mango, dragon fruit, and watermelon.

The calm and peaceful animation of the royal city and monastic center of Luang Prabang, refined across centuries, prepared us well for our lengthy journey by bus to the city of Vang Vieng the following day. Travelling south to Vang Vieng, we stopped at two villages to meet members of the Khumu and Hmong tribes, two of the fifty ethnic minorities in Laos, which has a total population of 6 million. Driving along the Khan River, which was lined with rice fields, we passed stilted bamboo houses, banana trees, pigs, and chickens. Our driver honked around the bends as we made our way up a mountain road flanked at the top by smoking fields.

The Khumu people, related to the Khmer, are farmers; their major crop is mountain rice, as was evident from the surroundings. We entered the village on foot, noting a sign given by the government in recognition of the village’s crime-free record. People squatted around wood fires in front of their homes against the chill of the mountain air. Like the pied piper, we attracted all the village children with bags of candy in our hands. Congregating around us, they received the candy with happy squeals, piercing the calm in the air. People appeared happy despite the apparent poverty. We visited a 90-year-old village elder and learned about animist shaman ceremonies for driving away bad spirits and making offerings to appease them.

Descending a road flanked by charred ground and blackened hills, we passed by workmen laying cable for telephone lines. Passing store fronts and an occasional motorcycle, we paid a toll to drive onto a paved road. Knowing how low salaries were, we suspected corruption at the sight of expensive cars. The landscape of surrounding hills was shrouded in smog. Villages with bamboo homes, laundry stretched between poles, and even big tour buses all appeared in silhouette. At 4500 feet we reached Phou Khoun (Mount Khoun), where we stopped for lunch.

The government has put an end to nomadic life. Now everyone lives in a village with electricity. We also visited a Hmong village. As soon as our bus pulled up, children and adults appeared at the doorsteps of their houses, which lined a hill. We walked up to visit them. A widow who lived with her mother, six children, and six grandchildren welcomed us to her two-room bamboo house. Despite the crowd living in this small space, the house looked neat and orderly. Everyone seemed to have a designated area, including the family dog sleeping in a corner.

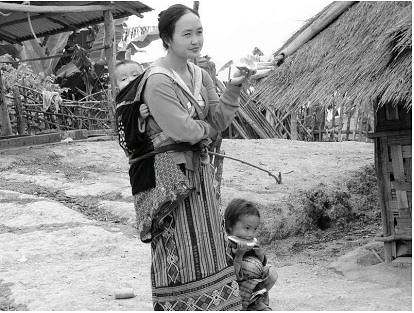

Hmong family

Originally from Mongolia, the Hmong are animist mountain people. Their language is similar to Tibetan. They have many children, and follow their own traditions and dress style. They are farmers, whose major crops are rice, corn, and chili peppers. After the monsoon rains, men make holes in the softened ground with a stick, and their wives then place seeds in these holes. In four months the rice is harvested using a sickle. There are two harvests each year; the rice field has to rotate every three years.

During the war with the Communists, the Hmong fought on the side of the King and the US. After losing the war, they escaped to refugee camps in Thailand, and the US took responsibility for them. The Hmong who stayed behind continued as terrorists, with support from their compatriots in America. The largest US population of Hmong is in Minnesota. Since there is no longer any anti-government activity by the Hmong, Laos has been open to tourists since 1999. Those who live in villages and have relatives in the US receive money from them and are able to upgrade their living standards. The one overweight person I noted in the entire village was a woman who had recently returned from visiting relatives in the US.

The Hmong make up 20% of the Laotian population. In Laos only those who work for the government receive benefits such as free health care. Though the country is nominally a Communist single-party regime, its economy is becoming increasingly capitalist. An Australian company operates a gold mine, and both Australia and Japan give scholarships to students to study abroad. How much of this opportunity trickles down to minority populations is hard to know. The candy we distributed to both adults and children had to suffice for now. They waved goodbye to us with big smiles.

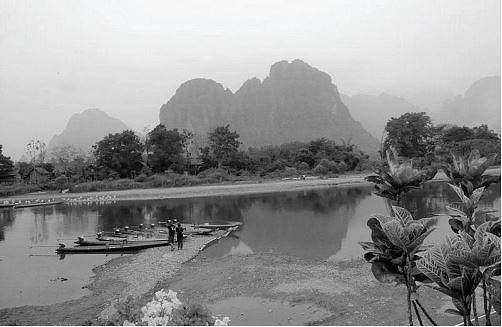

Continuing on a mountain road, we reached Vang Vieng, our overnight rest stop on the way to Vientiane. Vang Vieng is nestled in mountains, and its scenic surroundings are renowned for their topography. Trekking attracts backpacking crowds, who sleep in places charging as little as $4 a night. Even restaurants offer reclining chairs as rest stops. There is drug activity here; trading in drugs is illegal, and anyone caught with more than 500 grams of heroin faces a penalty of a long jail term or even execution.

Descending from our bus, which was too big for the narrow path, we made our way to the Thavonsouk Resort Hotel on the Nam Song River. The staff met us with a welcome cocktail of refreshing lemon tea. Our rooms, whose porches were bursting with tropical shrubs and flowers, faced the river and the silhouetted mountains beyond. For dinner we enjoyed pumpkin soup, ginger chicken, tilapia, and stir-fried vegetables, accompanied by a big mound of rice. A fresh fruit platter with a variety of melons and pineapple completed our meal. After dinner we were entertained by the hotel owner, who sang English songs from the 60s to guitar accompaniment and included a few Elvis songs for flair. This stopover in Vang Vieng was a perfect interlude on our long journey to Vientiane.

View of Nam Song River

In the morning we were back on the mountain road with its spectacular scenery. We passed by people cooking breakfast along the roadside. Students on bicycles — boys in white shirts with dark pants and short hair, and girls in white shirts and dark skirts — rode to school. We stopped to visit an organic farm. The founder had received his university education in Sophia, Bulgaria, and later joined a pro-Communist organization known as the Pathet Lao to free the country of colonial powers. He had worked for the government in forestry; he had then started his farm with two acres of land in 1996, gradually increasing it to five and then to twenty acres.

Dedicated to teaching environmentally friendly ways, the farm attracted international volunteers through its website to live and work there in exchange for accommodation. We visited an adobe house built by young people from Israel, and watched goats being milked and fed by volunteers from Singapore. Having started with four goats imported from the French Alps, the farm now boasted twenty, which provided milk for babies in addition to cheese. There are no dairy products in the traditional Laotian diet; such dairy products as can be found are generally imported from Thailand.

Mulberry leaf tempura

Organic produce was less expensive on this farm than ordinary produce, as vegetables with holes in the leaves do not look as pretty as those sprayed with chemicals. We walked among mulberry trees, citronella plants, lemongrass, and hibiscus. We were introduced to jackfruit, which tastes like potato and can weigh up to 30 pounds; it is eaten chopped or mashed. We enjoyed mulberry tea, made by boiling the leaves over a wood fire, then chopping the upper layer for high-quality tea and the part near the stem for low-quality tea. In the final stage the leaves are tossed by hand to bring out their aromatic flavor, then dried and packaged. We sampled sun-dried banana chips and mulberry leaf tempura, which were both delicious. I purchased a bag of mulberry tea, in addition to a scarf from silk produced on the farm. Proceeds from such purchases go to support an English school for villagers, who come to the farm to learn “the way of the future,” as Internet technology spreads through the country.

As we continued on our way to Vientiane, we learned that each group of twenty houses comprises a village. Every village has a chief, who makes sure people follow government regulations, such as displaying the Communist hammer and sickle flag in front of every house during festivals and voting every five years in parliamentary elections. Election Day is a holiday; people have to travel to their home towns to vote. All members of parliament belong to the Lao Revolutionary Party. They elect the Prime Minister and the President, who becomes the head of the Party.

We passed by rubber trees given by China. Rubber is exported to China and bought back as tires, rubber bands, and other finished goods. There is very little industry in Laos. Its only exports are agriculture, handicrafts, and electricity; even sugar is imported. The government owns the beer and cigarette industries. The main industry is tourism, with hotels generating tax revenue. Most mining companies — copper, silver, and gold — are operated by the Chinese. Bridges are being built across the Mekong for easier and faster transportation to neighboring countries. Cars and motorbikes are subject to 50% import duty and, therefore, very expensive.

At one point our bus began leaking oil. The driver, who seemed used to solving problems on the spot, wrapped up the leak with a rag and rubber bands, and we continued on our way. Farm life gave way to city life. We drove onto a paved road lined with shops. Bicycle and motorcycle tires wrapped in colorful foil hung from shop rafters like ornaments. Goods stacked outside of stores ranged from brooms, baskets, and flower pots to soft drinks and stupas for burial grounds. Modest single-story cement homes with shrines alternated with wooden houses with typical Laotian roofs. As traffic increased, so did the number of small roadside restaurants with pastel-colored plastic chairs and vinyl-covered tables catering to weary travelers.

As we approached Vientiane, European-style homes, clothing stores with mannequins, ornate temples, monks in saffron robes, tuk-tuks, beer ads, signs for banks and a dental clinic, and flags on official buildings signaled our much anticipated arrival in the capital city. Through a frenzy of motorbikes, we entered Vientiane (pronounced “Vieng Chan”) in the early afternoon. The rapid arrival of modernity was evident from the tangle of cables on telephone poles and English signs on many buildings, including banks, bookstores, and Internet cafes. We walked over to the Joma Bakery/Cafe to have lunch. This downtown self-service restaurant operated at a dizzying pace. I managed to order vegetarian lasagna and mulberry pie, and took my tray to an outdoor table to enjoy the sunshine. I ate quickly to join the buzz on the street.

It will not be long before Vientiane is like Asia’s other frenetic capitals. The city is a mélange of Lao, Thai, Chinese, Vietnamese, French, and American architecture, cuisine, and culture, giving it an almost-anything-goes flavor. The city has grand old buildings, along with a number of air-conditioned modern ones. It is evident that the city has a large share of the country’s wealth, though only 10% of the 6 million population live here.

Haw Pha Kaew Temple

Our tour began in a neighborhood which was once the administrative center of French colonial rule. The Presidential Palace, originally built as the French colonial Governor’s residence, is now used for hosting foreign guests of the Laotian government and is not open to the public. Nearby are the royal and religious headquarters. Haw Pha Kaew is the former royal temple of the Lao monarchy, built in 1565 to house the Emerald Buddha, which was brought to Laos from Thailand. Today the Emerald Buddha is back in Bangkok. The building, no longer used as a temple, has been restored; its two main doors contain parts of wooden panels from the original structure. The museum has famed Buddhist sculptures of the types common in Laos. The beautiful garden is a peaceful retreat from the dust and heat of Vientiane.

Across the street is Wat Si Saket. Built in 1818, this temple is the oldest original one in Vientiane. It contains a total of 6840 Buddha statues in varying sizes and positions. The interior walls of the cloister surrounding the central sim, where new monks are trained, are filled with specially carved niches containing more than 2000 small silver and ceramic Buddha images, most of them made in Vientiane between the 16th and 19th centuries. Today Wat Si Saket is home to the Head of the Lao Sangha, a Buddhist order of monks.

Our hotel, the Don Chan Palace, faced a riverfront boulevard that ran right along the Mekong at the southern edge of town. Vientiane owed its early prosperity to its location on the fertile alluvial plains on the banks of the Mekong River. The river is lined with reinforced dykes and a town wall built against overflowing waters; massive construction to develop the riverfront is ongoing. Outdoor cafes with a view across the river to Thailand offer food, fruit shakes, and beer. Due to the temperature, which was in the high 90s, I regretfully opted to stay in the air-conditioned hotel during free time, rather than exploring the waterfront.

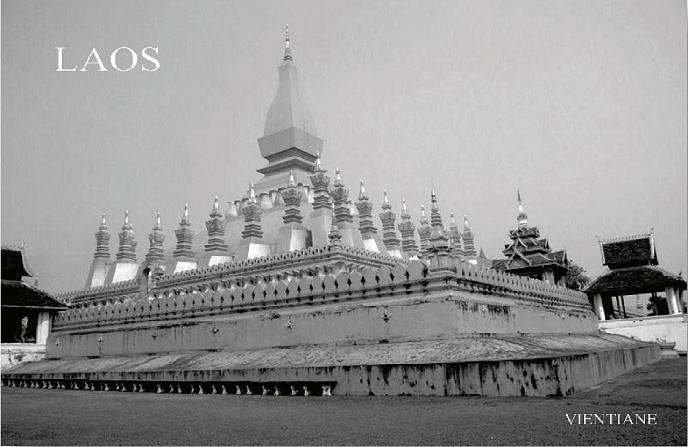

That Luang, also known as the Great Stupa, is the symbol of the Lao nation and the most important monument in the country.* The breastbone of the Buddha is believed to rest at this site. Built in the 16th century, the multilevel stupa represents the different stages in Buddhist enlightenment: The lowest level represents the material world, the second the world of appearances, the highest the world of nothingness. Restored by the French in the 1930s, the dome is covered in gold leaf. Buddhist visitors come with flowers, incense, and candles, and circumambulate the stupa clockwise three times — once for the Buddha himself, once for the scriptures, and once for the monks. Meanwhile, vendors on the grounds sell caged birds to passers-by, who pay to release them as a good deed.

* See postcard image at beginning of article.

The Patuxai, or Victory Gate, is Vientiane’s own Arc de Triomphe. It was completed in 1969 in memory of the Laotians killed in wars before the Communist revolution. Inspired by the French, it incorporates Laotian elements, such as Buddhist imagery in the moldings, and frescoes under the arches representing scenes from the Ramayana. Climbing the winding stairway to the top offered a splendid panoramic view of the city, including government buildings nearby.

Talaat Sao, the Morning Market, is a mall where people used to shop before going to work; the name has outlasted the custom. The market is a maze of individually owned stalls selling everything from textiles to jewelry and household appliances, including goods imported from China, Thailand, and Vietnam. It is worth a walk through, though the experience is one of sensory overload.

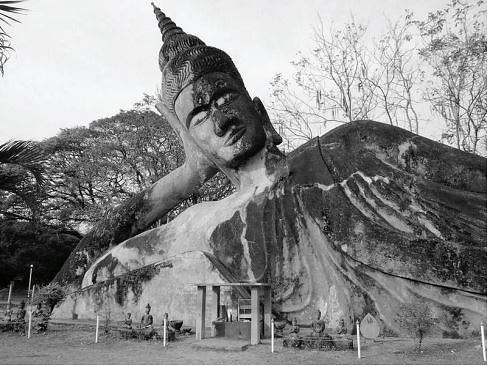

Buddha Park

A highlight was our visit to the Buddha Park, sixteen miles southeast of the city by the Mekong River. The park, also known as Wat Xieng Khuan, or “Spirit City,” has a collection of over 200 big concrete Buddhist and Hindu sculptures amidst frangipani, the national flower of Laos. It was built in the 1950s by a shaman priest, who merged Hindu and Buddhist traditions to develop a following in Laos and Northeastern Thailand. The numerous figures include images of Shiva, Vishnu, and the Buddha, as well as humans, animals, and demons, giving the place an air of fantasy. There is an enormous reclining Buddha, which is over 130 feet long. Dominating the park is a massive pumpkin-shaped structure with three levels, representing hell, earth, and heaven. It offers a good view from the very top, which is reached by a staircase inside the gigantic mouth.

On the way back from the park, we stopped by the river shore to see the Thai-Lao Friendship Bridge, completed in 1994 and funded by the Australian government. The bridge, which is three quarters of a mile long, connects Nong Khai in Thailand to Vientiane, and is symbolic of the opening of Laos to the outside world. Continuing to a weaving village near Vientiane, we admired silk shawls with traditional designs woven on hand looms with tie-dyed silk threads.

In the same village we visited a local mor kwan (shaman), to participate in a traditional bai sri su kwan, or rice offering ceremony. Shamans are certified by the government and must display their licenses where they practice. We were received in a room with two framed certificates on the wall. We sat facing an altar prepared with flowers, candles, and food — hard-boiled eggs, small bananas, and banana-and-shrimp chips. Holding a lit candle in a plate in his hand, the shaman chanted in a Laotian dialect, while we held on with both hands to white cotton threads tied to the altar. When he finished chanting, the shaman put a dab of rice wine in the hands of each participant, followed by an egg, and tied a white piece of thread around one of each person’s wrists to be kept there for three days. Thus, we were all blessed so we would have a safe trip and keep all of our 32 souls with us.

Hanuman monkey dance

On our final night in Vientiane, we enjoyed dinner and a traditional dance show with live gamelan music at a downtown hotel. We checked our shoes with an attendant and sat on low floor cushions to eat. As in all previous establishments, the menu offered a great variety of Asian food; the program included both court and folkloric dance. The court dances were stories from the Ramayana epic, and the folk dances depicted scenes from daily life, such as rice harvesting and fishing. Satiated both culturally and gastronomically, we returned to our hotel in anticipation of our trip to Vietnam the following day.

Long considered a backwater of Indochina, even during colonial times, Laos is changing fast. It is fully prepared to receive international visitors. The government sees tourism and related trade as a way to increase development and assure a prosperous future. Laos is startlingly beautiful, is inhabited by friendly people, and has varied cuisine influenced by the French culinary tradition. In addition, its deep-rooted Indic culture, the practice of Theravada Buddhism, and the rich mixture of ethnic populations with diverse handicrafts make Laos an extremely rewarding destination.

← Myanmar