March 2010

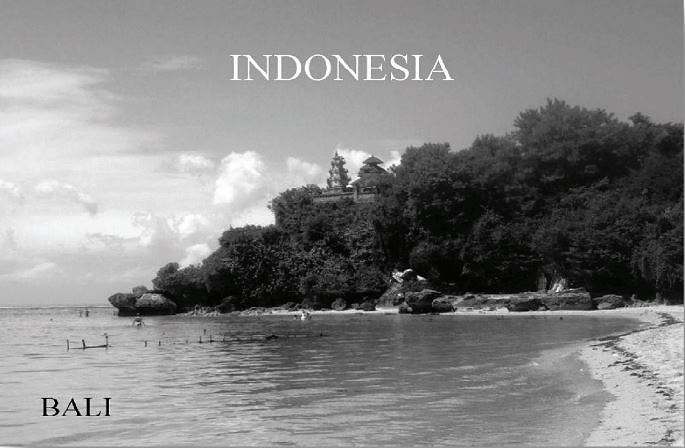

Leaving an extra bag at the Miracle Hotel on the way to the airport, I flew from Bangkok to Denpasar in Bali with Thai Airways. The four-hour flight began with sweeping views of the Chao Phraya River and rice fields, and ended in a field right by the ocean in Denpasar, capital of the southeastern part of Bali, one of 3000 islands comprising Indonesia.

Upon arrival, I purchased a visa for $25 in new banknotes, as I had been forewarned by friends that old-looking money would not be accepted. Walking into 94° heat seemed routine by now at the end of my month-long trip in Southeast Asia. My friends Baxter and Bill were at the arrival gate. This was my second visit with them since they had moved to Bali in 1990. The fond memory of my earlier visit with my late husband in 1991 was my impetus to return to this beautiful island, even if only for three days.

Offering in

bamboo basket

My friends used to live in Tirtagangga, inland and north of Denpasar. Their home at the time, near the grounds of the last Rajah’s Summer Palace, consisted of three bungalows, each functioning as bedroom, studio, and kitchen. Their current home in Denpasar is a small, renovated three-story former hotel near the beach. A staff of three men take care of the house — cleaning, cooking, and maintaining the garden. They also tend to fifteen shrines, both indoors and outdoors. Each shrine is adorned with flower petals, incense sticks, and bamboo baskets filled with offerings such as fruit and rice cakes. Early in the day the offerings are replenished; during the full moon the basket is exchanged for a new one. Incense permeates the house.

Camera in hand, I toured the house, admiring the local color of its furnishings. Baxter’s paintings adorned the walls, while his mosaic sculptures in unexpected spaces were delightful. Bill’s interest in gardening and cooking enhanced the beauty of the setting. The elegant dining room was set for four to include their other house guest, Phyllis. The staff served a delicious dinner of soup, salad, and tuna steak with pignolias, with strawberry custard tart for dessert. Shortly after dinner I retired to my room with its four-post bed, as I had had a long day. The fan was a welcome respite from the humid air.

In the morning we walked about to explore the neighborhood. Much had changed in Denpasar since my earlier visit nineteen years before. Incessant car and motorbike traffic, money exchange offices on every other block, and markets catering to expatriates signaled Bali’s emergence into modernity. Fortunately, Bali had retained much of the traditional while adapting to modern influences, as the Hindu religion is still the most determining factor in people’s lives.

A small island with an area of 2220 square miles, Bali is blessed with fertile soil supporting 3 million people, half of whom are Hindu. Until the late 15th century, Bali was part of the great Hindu-Javanese Empire of Modjopahit. As Islam spread to the western Indonesian archipelago, many Javanese princes — with their court entourage of musicians, poets, dancers, actors, sculptors, and craftsmen — migrated to Bali, thus adding an artistic stamp to the existing Hindu religion and way of life.

Cremation ceremony

In Bali art, life, and religion are intense and inseparable. There is always a celebration or ceremony going on — a blessing, sacrifice, purification rite, temple festival, procession, or cremation. On the street we passed by an ogoh-ogoh, a remnant of the recent Balinese New Year Celebration. On the day of the new year, people parade to the accompaniment of gamelan music, frightening away evil spirits by carrying scary creatures made of papier maché over bamboo. Gamelan music, shadow plays, dramatic dances, and theatrical performances permeate daily life. Classical, refined, and traditional performances inspired by Hindu epics such as the Mahabharata and Ramayana take place in temple yards, in village squares, or under banyan trees.

Neighborhood shrine

Every town or village has a number of temples, and each home has its own temple, ranging from modest to elaborately carved shrines. There are temples in rice fields, on beaches, and on hilltops. We visited a Taoist temple, built around the oldest temple structure in Bali by the island’s Chinese population, who had no citizenship status until ten years ago. One must be born into the Hindu religion; it is impossible to become Hindu by converting later in life.

Cities are divided into banjars, or communities, each one with its centrally located temple, meeting point, and resting place in the shade. Death ceremonies are held in a separate temple built for that purpose. Each village has its own troupe of dancers and musicians. These perform and entertain as accomplished masters of arts which they have learned since childhood and which have remained central throughout their lives.

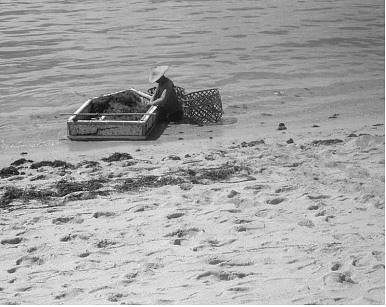

Collecting dry seaweed

The Balinese make use of the sea around them. At Nusa Dua, near where I stayed, locals searched the white sandy beach, collecting dry seaweed to sell to the cosmetics industry for use in beauty products. At Tanjung Benoa Harbor, men cast nets for fish and crabs, while others arrived in big boats from the island of Sulawesi and fished off the coast of Bali to supply hotels and restaurants. Sales were brisk, as women sold colorful fish, big and small, by the bucketful.

Land on Bali is so fertile that the rice harvest is plentiful; coconut grows profusely; and sugar cane, coffee, cocoa, tobacco, indigo, and peanuts are abundant. Rich harvests are due in large measure to irrigation systems, which follow the lay of the land, helping to shape the island’s beautiful landscapes.

The Balinese are superb wood, stone, and horn carvers; they also excel in crafting gold and silver jewelry. Women everywhere are skilled in weaving colorful sarongs. In the ikat technique, a design is dyed into the threads before they are woven, resulting in beautiful textiles. About seventeen miles from Denpasar is the art colony of Ubud, where most craft shops congregate. Here, in addition to traditional crafts, contemporary expressions of native Balinese art forms may be found.

Batik is yet another craft the Balinese are known for. In a batik shop in Denpasar, I bought a kebeya, a traditional blouse for women worn with a sarong. Since Bali was the last destination on my month-long trip, I had no room left in my bag to pick up other local crafts. However, I returned home with my already indelible memories expanded. Processions of beautiful, lithe women carrying crowns of flowers and fruit as temple offerings; the refined facial gestures and precise hand movements of graceful dancers; the clear, percussive hammering sounds of a gamelan orchestra; the trance-like fire dance; the frenzied, dramatic ketjak, or monkey dance; and towering funeral pyres reflecting the Hindu belief in reincarnation, with children scrambling afterwards for coins in the ashes — once experienced, such images remain forever.

Also unforgettable is the heavy traffic, which becomes hectic during rush hour — a sad reminder that the time left for pleasure is diminishing, as Indonesia strives to join the ranks of the developed countries. Following a most relaxing full-body treatment at the house by a masseur — with conventional modesty abandoned — and a refreshing tropical fruit plate for lunch, I left for the airport for my return trip.

In Bangkok, I was met by a staff member of the Miracle Hotel, which is 20 minutes from the airport. Upon arrival at the hotel, I went to bed right away, as I had to be back at the airport by 3 am to fly to Tokyo for my US connection. The Bangkok-to-Tokyo flight took four hours, following which I flew to Minneapolis. During this ten-hour leg of the flight, twelve attendants on board spoke either Chinese or Japanese in addition to English. Next to me sat a Laotian couple who were returning from a visit to their native country. They had relocated to Nashville, Tennessee, where the husband worked for Japanese auto maker Nissan. My recent visit to Laos led to a lively conversation during this serendipitous encounter in the air.

Finally in Boston after a month-long journey, I felt exhausted, yet exhilarated. Southeast Asia still remains one of the most fascinating parts of the world for me.