October 2004

Our trip leader, Djenane, welcomed us at Cairo airport, where our group expanded by four people to fifteen. An attractive Egyptian woman with a degree in Egyptology, Djenane accompanied us throughout our itinerary. By request from the US, the Egyptian government provides a police escort at its own expense for each American tour group. In addition to the presence of the Tourism and Antiquities Police at all sites, armed police in a separate vehicle shadowed our van as we traversed the country.

The capital is Cairo, where a quarter of the country’s population lives. On the right side of the Nile is Cairo proper and on the left side is Giza. Together they constitute Greater Cairo, which has 17 million residents. A workforce of 3 million commuters brings the total to 20. Traffic crawls; no one observes lanes or lights. Since our trip coincided with the holy month of Ramadan, congestion was at its peak as people rushed to get home in time to break their fast at sundown. By 2 pm commuters were already heading home.

Our introduction to Egypt began with a visit to the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities. On the way we stopped by the Anwar Sadat Memorial and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, dedicated to those killed in the Six-Day War with Israel in 1967. As our driver maneuvered his way through the traffic, we passed by the Colossus of Ramses II and a statue of Nobel laureate writer Naguib Mahfouz. In downtown Cairo minarets of mosques and crosses on top of Coptic churches dotted the skyline. Egypt’s population is 80% Muslim and 20% Christian. The lotus flower, the symbol of modern Cairo, appeared as a motif on many buildings, along with advertisements in pictorial Arabic script.

Our visit to the Museum was a crash course in Egyptology. We walked through time as we covered the highlights of each kingdom, including the treasures of King Tutankhamun. Looking at many funerary relics, we learned how to discern, by the curvature of their beards, whether statues of kings had been made during their lifetime or afterwards, and how organs had been preserved in exquisitely carved alabaster jars. This vast museum, filled with antiquities, was a fascinating place, but the old building lacked air-conditioning. The enormity of the crowds jostling for space, each with a tour guide speaking one of many tongues, contributed to the discomfort. Our museum experience was a trying one.

Early the next morning we flew to Luxor, the site of ancient Thebes. The Thebans built extremely elaborate places of worship for their local god, Amun, who they united with the Egyptian sun god, Re, to worship as Amun-Re. Built on the East Bank of the Nile, these temples were seen as greeting the rising sun each morning. Over on the West Bank was the land of the dead, where the sun went down each day. There the pharaohs, worshiped as living gods, built their own funerary monuments. For millennia, successive kings and queens replaced or expanded existing monuments in ever grander styles.

Karnak is a very large temple complex covering an area of 100 hectares. Its original sanctuary was built during the Middle Kingdom (around 1900 BC) and expanded by the rulers of the New Kingdom. An avenue of ram-headed sphinxes leads to the Great Court, which opens onto the Great Hypostyle Hall, filled with 134 enormous columns, each 50 feet high. Through another courtyard stands the tallest obelisk, 100 feet high, cut from a single piece of pink granite and raised by Queen Hatshepsut in honor of Amun. Continuing, we came to the Sacred Bark Shrine, where the bark of Amun would have rested. Barks were scale models of the vessels on which the gods were believed to travel the heavens. Among the fascinating aspects of this open air museum were pictorial hieroglyphs on the facades of the monuments, along with pharaonic stories in bas-relief. The Colossus of Ramses II protects his wife, who is placed between his legs.

In the afternoon, we visited the Franciscan School and Orphanage, an institution run by Franciscan nuns. The school follows the Arab-language curriculum mandatory for all schools in Egypt, with English as a second language. As boys and girls attend Sailing on the Nile school separately, the girls do not wear headscarves. In the second-grade classroom there were 55 students, seated three to a desk. Because of the large size of the class, all activities were done as a group, even during recess. Education is compulsory through the sixth grade; parents look upon children as a source of income, especially in rural areas.

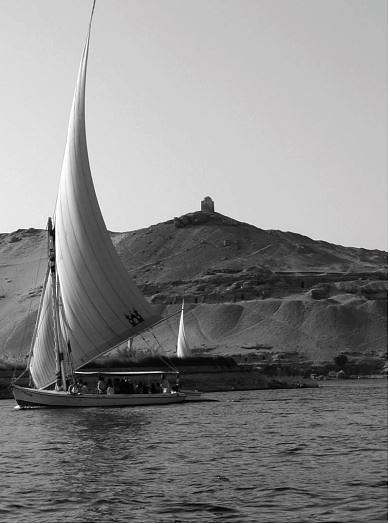

Sailing on the Nile

Before sunset, we boarded a felucca for a cruise on the Nile. A felucca is a broad sailboat, like those designed by the ancient Egyptians to ferry stones and other heavy objects from shore to shore. With their fin-like sails sewn from vertical strips of cloth, feluccas are now iconic pleasure boats on the Nile. As we sipped non-alcoholic beverages, we watched the sun set gradually beyond the shoreline. In the evening we visited the Luxor Temple, dramatically accentuated by floodlights.

A sunrise farm breakfast was the next morning’s treat. In the dim early light, we crossed to the West Bank of the Nile in a motorboat and watched the sun rise on the eastern shore. Amidst banana trees and date palms and against a backdrop of large colorful fabrics with bold prints, we sat on low stools around tables set with baskets of freshly baked bread and trays of olives, goat cheese, tahini, yogurt, tomatoes, and other breakfast fixings. We also enjoyed fatir, a flaky pastry filled with thin layers of cheese and accompanied by coffee or tea.

Ramadan decorations of small flags on strings crisscrossed above my head as I strolled through the streets of the village. Mud brick houses strengthened with dry palm leaves lined the roads. The houses had straw thatched roofs, and painted doors and shutters. Old men slept on wooden cots outdoors, mothers tended to their babies, young men and children in caftans headed to nearby farms with their animals, while others in uniform walked to school. Among rural people, unmarried women wear colorful clothing, which they cover with a transparent black coat upon marriage. All-black dress is for old age or widowhood.

Following the 1952 revolution and the founding of the Egyptian Republic, farmers received free land — 100 acres per family or 50 acres per person. Agriculture is a major source of income for Egyptians, in addition to oil, tourism, and commerce on the Nile. Cotton, called “white gold” by the locals, is a major crop; others are sugar cane, wheat, corn, beans, and many other vegetables. Popular drinks are hibiscus tea and sugar cane juice. The former is thought to be good for the heart, and the latter for the kidneys.

Our visit to the West Bank included the Valley of the Kings, with its 64 pharaohs’ tombs, and the Valley of the Queens, with 57 tombs of royal family members discovered so far. The tombs are chiseled deep into the cliff sides of the sun-scorched valley. Splitting from the group, I was able to cut through the crowds and descend into a few of the subterranean chambers. Decorated from floor to ceiling with mysterious images of the afterlife, the sunken tombs are extraordinary. As soon as a pharaoh ascended the throne, he began planning his royal tomb. Those who died young were at a disadvantage for completing lavish tombs, which had to be ready for the mummified body within 70 days of death.

The West Bank tour included stops at the Colossi of Memnon, as well as an alabaster shop. The Colossi are a pair of massive 64-foot-tall statues of Amenophis III, made of yellowish sandstone. Their eyes are cast toward the Nile. The statues were given the name “Memnon” in the Roman imperial era, after a soldier who had fallen in the Trojan War. A shop near the quarry was an opportunity to watch craftsmen chiseling and filing blocks of stone into beautiful objects, which acquired a translucent quality when held up to the light.

During free time back at the hotel, I decided to venture to the souk (market) on my own. Wearing a blue bead charm to ward off the evil eye, which Egyptian folklore shares with that of Turkey, I decided to disclose my heritage if asked. I wanted to find a store where I could purchase the brightly colored fabric that I had admired during the farm breakfast. Among bolts of fabric stacked outside a small shop, I spotted it. Any pause instantly leads to an invitation to go in, so I did. As a Turk, I received a very warm welcome and, without having to bargain hard, walked out with two meters of fabric, plus some extra cloth for friendship. At another shop, I received a gift of a T-shirt with an embroidered cartouche — a hieroglyphic seal used by the pharaohs. Mine said “Egypt,” as there was no time to have it personalized.

The highlight of the trip was a hot air balloon ride, a first-time experience for me. I loved drifting through the air in the basket of the balloon. We enjoyed a bird’s-eye view of Hatshepsut’s Temple and the farmland below, as we hovered over fields of corn, sugar cane, okra, and sesame plants. Houses with color-washed facades on the hills and farmers in caftans harvesting with hand tools dotted the pastoral landscape.

A trip to the Luxor Museum, which holds a collection of ancient Egyptian funerary items and statues found in and around the city, offered an unexpected contrast to our experience in Cairo. Treasures here are displayed in an attractively lit and air-conditioned environment. All the exhibits are well labeled. The Wall of Akhenaton, found in the Karnak Temple, depicts daily life and religious rituals during the reign of Akhenaton, whose monotheism, although short-lived, was a revolutionary force in Egyptian culture.

Boarding our Nile River cruise ship, the M/S River Hathor, offered a welcome change to the heat on land. The crew greeted us with refreshing hand towels and a warm lemon drink to acclimate our bodies to the change in temperature. We set sail for Esna, where cruise boats pass through the Nile Lock. Only two boats can go through the lock at a time, so we had to wait four hours for our turn. At around 10 pm, I finally watched the water raise our boat to its passage. This was yet another first for me.

The Nile is a busy waterway with many cruise ships, as well as cargo and fishing boats. Loud horns sound as ships pass one another; cargo boats carry lumber or stone from quarries. Forgoing the onboard swimming pool, I viewed the river banks through binoculars as the landscape shifted from industrial to rural. Smokestacks on coal-fired power plants spewed black smoke, covering high-voltage towers in haze. Fishermen whipped the water to scare fish into nets. Farmers worked the fields. Children tended to horses and donkeys. Palm trees and sugar cane fields filled the lush shoreline.

Our first visit ashore was to Edfu, which is a regional center for sugar cane trade halfway between Luxor and Aswan. We rode a horse-drawn carriage to the souk, to buy vegetables for a cooking lesson on deck by our cruise chef. Given a list of ingredients for okra stew, the group dispersed in the market. Bargaining was a challenge as we shopped for tomatoes, peppers, and onions by the kilo. Small Egyptian okra changed my attitude toward this vegetable, as we consumed all of the four kilos that we bought.

Falcon by the gate to the Temple of Horus

Edfu is home to the splendid Temple of Horus. This was built in Greco-Roman times according to the principles of ancient Egyptian architecture. Almost buried until the mid-19th century, Edfu sat on the roof of the temple when excavations began and the mud brick houses were pushed back. The ancient Egyptians believed that Horus, a falcon-headed god, dwelt in the temple as their divine protector. Two statues of Horus as a falcon flank the entrance gate.

Back at the ship after our Egyptian dinner buffet, we had a costume party. We bought some traditional galabeyas, (embroidered caftans), which we enjoyed dressing up in. Sequined headscarves and veils were popular among the women, while men donned typical red-and-white checkered or black head covers held in place with Arab headbands. The most distinctive element of my costume was a pharaonic necklace; a two-inch-wide band of ceramic and metal beads circled the neckline of my dress.

Our cruise ship docked at the ruins of Kom Ombo, another Greco-Roman temple. Dramatically set on the riverbank, this is a double temple with one side dedicated to the crocodile god, Sobek, and the other side to the falcon god, Horus. Symmetrical along its main axis, the temple has two of each element, one devoted to either god. The crocodiles that used to bask on nearby sandbanks are now extinct.

Our approach to Aswan was beautiful; the Nile flowed through amber sand hills and granite rocks and around islands of tropical plants, with the picturesque city set on the East Bank. Slow-moving sailboats signaled a relaxing, idyllic life. The outside temperature was 41°C (108°F) when we stepped ashore.

Fortunately, our first tour was a felucca ride to the Botanical Gardens. The captain of our boat was a dark-skinned Nubian with fine features and beautiful white teeth that matched his flowing caftan. Unexpectedly, a rowboat appeared next to us and two young boys broke out in song looking for baksheesh. As they sang “Row, row, row your boat,” they charmed us into giving them money. Our captain revealed to us that he too had grown up singing on boats to earn a living.

Following a pleasant walk through tropical trees, we returned to our cruise ship, moored in Aswan, for our farewell dinner and night. The kitchen crew and waiters outdid themselves in service, elegance, and creativity, including guest towels twisted into hanging monkeys in the corridors leading to our cabins. A Nubian folklore show featuring music and dance was the after-dinner treat. We sadly disembarked the next morning, knowing that we would not find such a friendly crew, or such luxury and pampering, in any hotel, however many stars it might have.

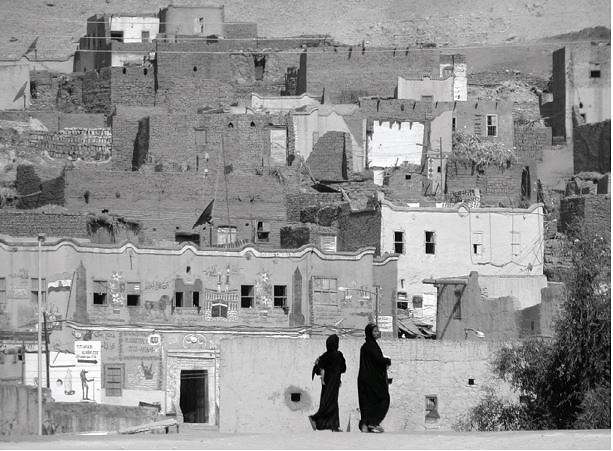

Aswan is a city of 300,000 people. It is famous for its quarries and is built on granite. A gateway to Sudan, the city has a distinctively African atmosphere, with its Nubian-style architecture featuring domes that work as air-conditioners. The old Aswan Dam, built by the British in 1902, was unable to control the Nile for irrigation, despite its later expansion. With financial help from the Soviet Union, 30,000 people and 2000 engineers built the High Dam in the 1960s, forever changing Egypt. The new dam brought cheap hydroelectric power to all villages and helped farmers protect their crops from flooding. Lake Nasser, the world’s largest manmade lake, not only relegated crocodiles and hippos to the southern part of the Nile, but also submerged old Nubia, displacing its culture and gold-rich land.

The temple complex at Philae, in southernmost Egypt, was nearly lost under water when the High Dam was built. An international rescue operation, sponsored by UNESCO, dismantled the temple structures and reassembled them in their entirety on nearby Agilkia Island from 1972 to 1980. The complex is a blend of Egyptian, Greek, and Roman architecture. The main Temple of Isis has courtyards flanked by granite lions, and walls covered with depictions of ancient gods and goddesses. A recognizable sight is Trajan’s Kiosk, where a sacred barge with the statue of Isis landed during its annual procession down the river.

Our visit to a papyrus shop was yet another fascinating discovery. Papyrus is a 5000-year-old tropical reed that grows along the banks of the Nile in Lower Egypt. Considered a sacred plant, it became the symbol of Ancient Lower Egypt. A cross section of a papyrus reed appears to be triangular, hence the inspiration to ancient Egyptians to use this shape in many aspects of their lives, including the Pyramids. We watched a craftsman make paper by slicing the plant core into strips, which he then soaked in water and pounded flat. Placing the strips side by side and layering them with a second set at right angles was the next step. After a second pounding the strips were left to dry under a weight, followed by a final stage where they were polished to a smooth surface by being rubbed with a stone.

Contemporary artists draw or paint on papyrus paper using traditional techniques. The shop gallery had a selection of such paintings for purchase. I bought two works. On the way to a Nubian village One is a Tree of Life with five birds perched on its branches. Each bird symbolizes a different stage in life — infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age. The first four look ahead, facing the future; the last one looks back, contemplating the past. Since I had been writing my memoirs, I could readily identify with this last bird. My second painting shows daily life in ancient Egypt, depicting rows of farmers, shepherds, fishermen, and other people, each accompanied by hieroglyphs.

In Aswan we spent three nights on Elephantine Island. Our hotel, featuring a sky tower, provided a view of the city and the islands all around. We visited the Coptic Monastery of Saint Simenon by motorboat. On top of a sandy hill stood the Mausoleum of the Aga Khan, built by his wife, Begum Aga Khan, who is also buried there. From the landing we reached the monastery on camel back and were met by a local Coptic guide. He gave us a tour of the fortress-like structure, built in the 6th century to honor a local saint.

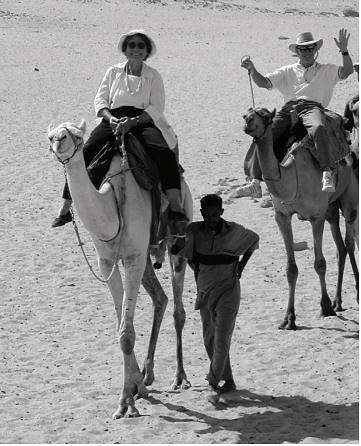

On the way to a Nubian village

Afterwards we reconnected with our camel taxi for a ride to a Nubian village — a new experience for me. I very much enjoyed the camel ride and felt comfortable sitting on the saddle placed between the humps. The camel driver, a young boy, showed me how to lean back when the animal changed from a sitting to a standing position; the boy accompanied us on foot, singing along as we crossed the desert.

The folk art in the Nubian village was a feast for the eyes. We had tea in a mud brick house with vaulted ceilings. The walls were decorated with colorful flat disks wrapped with yarn or raffia. Handmade baskets of varying sizes sat on a mantelpiece. Our hostess wore a long pink dress and a bright blue headscarf. She offered to tattoo our hands in henna for a nominal price. Forgoing the tattoo, I went outside to explore. Next door was a mud oven for baking “sun bread,” so called because the dough rises with the heat of the sun. I walked down the sand-swept street to a courtyard surrounded by plastered or color-washed houses. Each was individually decorated with moldings and with tracings in mud. The distinctive decorations accentuated the walls with nature imagery or abstract designs, and some included ceramic plates set into the plaster.

Nubian village

An early morning flight took us south to Abu Simbel, the site of two temples honoring Ramses II and Nefertiti, his queen. The temples were originally built into a rock face 50 kilometers from Sudan. Threatened by the rising waters of Lake Nasser, the entire complex was cut into 1036 blocks weighing 11 tons each. Over four years, 25,000 workers moved Abu Simbel, block by block, 600 feet inward and 200 feet upward, safely reestablishing it above the new water level; the project was completed in 1968.

Four 66-foot colossal statues of Ramses, each seated on a throne and wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, dominate the facade of the main temple. The smaller temple has four 33-foot statues of Ramses and two of Nefertiti. After walking in and out of the temples astonished and exhausted, I joined the group for our return flight to Aswan.

A stroll through the spice market offered a rich experience for the senses. The intense colors of heaps of spices were complemented by their smells in the air. I bought a bag of hibiscus tea, karkade in Arabic; equally irresistible was pita bread fresh out of the oven. A kunafa maker worked with thin strands of shredded wheat rolling off a cutting disk and onto a big brass tray. An old-fashioned knife sharpener reminded me of my childhood in Turkey; such men used to call out to homes in my neighborhood to announce their arrival.

We returned to Cairo for our final three days, staying at a hotel in Giza with a view of the Pyramids. On the first evening we joined an Egyptian family for a home-hosted dinner in an upscale neighborhood. Our hostess greeted us with her three sons, aged twelve to eighteen, and apologized on behalf of her husband, who was out of town. The spacious condominium was beautifully furnished and had wall designs custom-made by our hostess, who was a professional interior decorator. We served ourselves from an Egyptian buffet and sat at two elegantly set tables. Our hostess wore a long tunic over western-style slacks and had a waist-length headscarf. She explained to us that she needed to cover her hair since there were male guests among us.

In Giza our discovery began at the Solar Boat Museum, which housed the world’s oldest planked vessel, discovered in a pit at the foot of the Great Pyramid in 1954. This ancient boat from 3000 BC carried the mummy of the pharaoh from Memphis (Cairo) to his pyramid tomb, and was then buried to provide transport in the next world. Conservators have been able to reconstruct the 144-foot-long vessel from more than 1000 extant components without using any nails, just as the original was built.

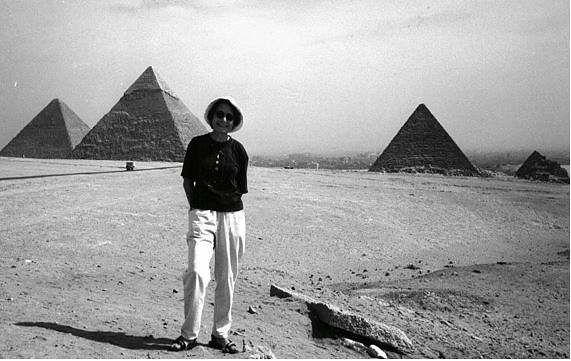

The Great Pyramid of Khufu is the first and largest of the tombs built in the Old and Middle Egyptian Kingdoms. 100,000 workers using large, irregular stone blocks constructed it over a period of eight years. The structure stood 480 feet tall when completed. The second largest pyramid in Giza is that of Khafre, Khufu’s son. The Pyramid of Menkure with its granite surface is the smallest of the three, standing at 203 feet. Each year in November, a production of Verdi’s Aida is staged with the Pyramids as a backdrop. I too had to have a picture taken here.

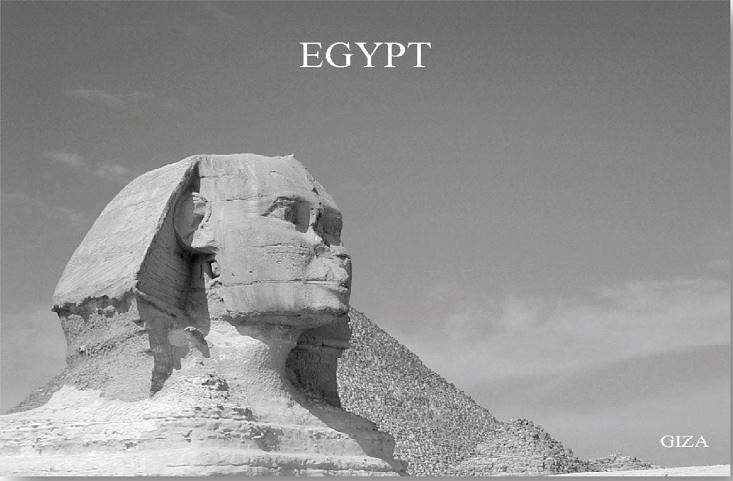

The Sphinx of Giza* is at the foot of a causeway leading to the Pyramid of Khafre. Carved out of rock left over from the pyramid, the Sphinx has the body of a lion and the face of a human. The body symbolizes strength, the face — wisdom. The nose of the Sphinx has eroded due to sandstorms; its beard is in the British Museum.

* See postcard image at beginning of article.

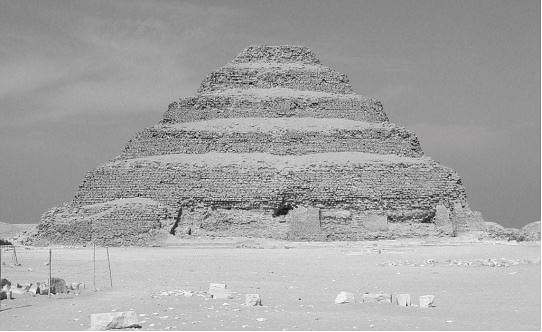

A scenic drive 16 miles south of Giza took us to Saqqara, the necropolis of the Old Kingdom pharaohs, who ruled from nearby Memphis as of around 3000 BC. On the way we passed by slash-and-burn farmlands and cabbage and okra fields, along with villas owned as second homes by the wealthy. We saw pigeon towers made of mud, and found out about date palms, learning that only the female trees bear fruit. The centerpiece of Saqqara is the Step Pyramid of King Zoser, built in 2700 BC. Over 200 feet tall, it is the oldest stone structure in the world. Stacked up mastabas, each smaller than the previous one, create a step-like effect, hence the name of the pyramid. A mastaba (the word means “table” in Arabic) is a flat burial mound for royalty.

Step Pyramid of King Zoser

On our way back we stopped at a carpet weaving school, where children come to learn the craft after attending school for half a day. School systems run two sessions a day because of the large numbers of students they have to handle. There are more than 200 carpet schools in the country, each training 40 to 50 children. We watched children at looms tying knots at amazing speeds with their small, flexible fingers. Considering their limited options between working here for pay and helping their parents in the fields, I looked upon these schools as the lesser of two evils in exploiting children.

Our busy morning ended with a late lunch at a local outdoor restaurant. After an array of cold appetizers followed by warm ones, we enjoyed chicken grilled nearby on charcoal braziers. A dip in the hotel’s pool refreshed us for the evening’s outing back to the Pyramids. A sound and light show took us on a historical journey that was the best among several we attended at ancient sites in the evenings.

On our last day we walked the cobblestone streets of Old Cairo, stopping at the oldest Coptic Church and one of the oldest synagogues in the world. We drove through Cairo’s Islamic quarter and ascended to the Citadel, a medieval fortress built in the 12th century by Saladin against attacks by the Crusaders. The sweeping view from here takes in the densely packed old section of Cairo, including shanties built on top of cemeteries, giving this quarter the name “City of the Living Dead.”

Situated on the northern heights of the Citadel is the Ottoman Muhammad Ali Mosque, also called the “Alabaster Mosque” because of the material that covers its walls. It has an arcaded courtyard, two slender 270-foot minarets, and a vast prayer hall with a 170-foot-high dome. A short drive away is the Khan El Khalili Bazaar, where we enjoyed lunch at a traditional Egyptian restaurant. After an orientation tour, we set out on our own to explore the sprawling bazaar, built in 1382. Tiny alleyways lined with hundreds of shops specializing in everything from antiques to belly dancing costumes reminded me of the Covered Bazaar in Istanbul. My only purchase was a hand-blown glass vase with a serpentine design around its neck.

The 45-minute drive back to the hotel was an opportunity for me, gazing out the window, to take stock of Cairo, a city so beset by urban migration that what used to be its perimeters has now become its core. Apartment buildings which once had a view of the Nile now overlook cemeteries. The beltway that circles the city has turned into a sea of trash. Municipal services cannot keep up with the sprawl, as people crowd into shanties without electricity or sewage. Traffic is like a three-ring circus with buses, trucks, and cars all jumbled together. Yet the city is a historic treasure alive with sights, sounds, and aromas, all of which were accentuated during Ramadan, as “tables of mercy” stretched out to feed the poor under colorful canopies by all the mosques.

Pyramids at Giza