ANDES

The Andes form the spine of Ecuador, running from north to south, with the east-west range positioned like rungs on a ladder, separating valleys 7-9000 feet deep. These valleys, with fertile soil beneath a range of dormant and active volcanoes, are heavily settled and farmed, and have been home to different ethnic groups since before Incan times. The towns are connected by railroad and by the Pan-American Highway.

Our bus journey started in Quito during morning rush hour traffic, as we descended through heavy fog into the valley surrounding the city, settled by Quechua people from the mountains. Bobbing up and down on the trail, which had been built by the Incas and was called the Avenue of the Volcanoes, we connected to the Pan-American Highway, which runs from Columbia to Peru. We passed by lush green fields, farms, cows, pigs, sheep, and unfinished adobe buildings, which are generally completed as their owners save up money. Heavy rains in the past two years had ruined crops, resulting in increased food prices. To protect the local economy, the government levied high taxes on imported products.

As we traveled through the Machachi Valley, the scenery changed to fields of potato, as well as broccoli, which is processed into cow feed to improve milk production. A refreshment stop in the town of Lasso rewarded us with a view of a red locomotive dating back to the 1950s. This museum piece still runs along the mountain tracks. A side road from Lasso brought us to the Hostería La Cienega, a former Spanish-owned hacienda (estate), now a hotel and restaurant. The main house — a stone mansion with large windows, stone-cobbled patios, and Moorish-style fountains — was built in the mid-1600s, with a stone chapel added later on. Walking down an alley of eucalyptus trees, we arrived at the main building, which was furnished with elegant period furniture and opened onto formal gardens in the back.

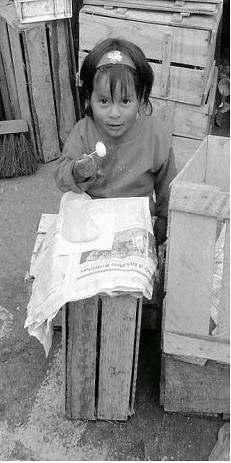

Tuesday market

Enjoying partridge egg

A major town on our itinerary was Latacunga, a city of 40,000 people founded by the Spanish in 1600 on a former Incan site; many of the buildings here are constructed from local gray volcanic rock. Latacunga is the capital of Cotopaxi Province and its commercial center. Our trip coincided with the town’s Tuesday market. Snacking on roasted, salted corn, we wandered through stalls of vegetables and fruit, attended by indígenas in felt hats and colorful skirts. Mothers shopped, carrying babies in shawls on their backs. A vendor tried to entice a crowd of onlookers into buying medicinal herbs, while shoe-shine men and women hailed down customers across the way. Tasting partridge egg was a discovery.

As we headed south, our next point of interest was Casa de Naranjo, an 85-hectare greenhouse where red, white, yellow, and hybrid roses are cultivated. Ecuador is a major exporter of roses throughout the world; Russia is its biggest market. Roses are cultivated year-round; the delivery time is two months. Cut roses are brought indoors and wrapped in plastic nets before being dipped into a solution to rid them of insects. After the stems are resized for special orders, the roses are packaged in units of 20 and crated. Under refrigeration until picked up in freezer trucks, the crates are shipped overnight in temperature-controlled flights and met by other freezer trucks at their destination.

Lunch at a place called Las Casas del Pérez in the town of Salcedo was the highlight of our day. Built by an artist and his wife, the adobe house was their home, studio, and gallery, as well as a restaurant. Before I could sit down at the beautifully set table, I had to look around. Evidence of Mr. Pérez’s creativity was everywhere — in stained glass windows, a sculpted and painted stairway, large and small table ceramics, and walls adorned with acrylic paintings.

Learning that everything was for sale, I settled down to eat quickly. The first course was humita — dough of white corn flour, spices, and butter — rolled and wrapped in corn husks before being steamed, and served with optional hot sauce. The main dish was roast chicken, accompanied by creamed carrots and mashed potatoes and followed by meringue with blackberry sauce. Afterwards, I departed with one of the artist’s paintings executed in his unique style — thick bronze acrylic paint outlining simple forms and colors. The painting depicted palm trees, houses, and people of coastal Ecuador in contrasting planes with shades of brown and green, accented with copper dots.

As we drove through Salcedo, parents crowded school gates to register children at the public school of their choice. Schools are in session from 7 am to 1 pm, and operate on a trimester system. Outside the town, broccoli fields gave way to alfalfa on the way to Ambato, the capital of Tungurahua Province. We passed a candy stand, where a man spun toffee out of brown sugar. Ambato is famed for its local food, spit-roasted guinea pig served with mashed potatoes and peanut sauce. Low in cholesterol because of their grass-only diet, guinea pigs are killed quickly by having their skulls smashed. People travel long distances to Ambato for this local food.

The landscape outside Ambato is of emerald mountains. Every inch of the vertical hillsides is farmed, turning the land into a patchwork quilt of every shade of green. Streams run in ravines, cows graze, an occasional farmhouse appears, and clouds shrouding the peaks of the Chimborazo Volcano at 20,000 feet add to the superb views. Chimborazo Province has the highest density in Ecuador of indigenous people, who also breed bulls for fighting — a legacy of the Spanish.

Stopping at the town of Posada La Estación in Chimborazo provided us with insight into the native lifestyle and crafts. Llamas, happy at high altitudes, graced the landscape. In a native hut filled with smoke, a woman kept a fire going to keep her guinea pigs warm. The animals lived in a sectioned grassy corner near a straw sleeping mat, shared by adults at night.

The artisan shop nearby had craftsmen at work. One sanded and carved “vegetable ivory” — as the egg-sized seeds of the lowland tagua palm are called — into decorative objects and jewelry. The soft seed hardens to an ivory-like consistency when peeled. Another artisan painted naive scenes on sheepskin stretched in a wooden frame. Both crafts enriched my folk art collection.

Driving another hour by lush high-altitude fields of oats and broad beans, we arrived at 5 pm in Riobamba, capital of Chimborazo Province, where we spent the night. Having been on the road since 7:30 am, we were ready to settle into our hotel, the Abraspungo Riobamba, which was beautifully furnished with country antiques and folk art. Instead of numbers, the guest rooms had names. Ours was named after the volcanic district of Illizi in Algeria. At dinner, we enjoyed vegetable soup, dolphin, broccoli, squash, mashed potatoes, and chocolate cake. Aji — a hot sauce made of orange-colored “tree tomatoes,” onions, and red peppers and used by locals on everything but dessert — was available for additional flavoring.

In the morning I walked around the hotel to see its collection in daylight. I was intrigued by a wall display of white handmade fedoras (felt hats), worn especially for fiestas and other special occasions. The hats varied in size and shape of brim and crown, as well as color and length of streamers and tassels, all indicating the wearer’s community or ethnic group. Dark, commercially made fedoras are increasingly replacing white ones.

Riobamba is the site of Ecuador’s military base, because of the city’s geostrategic location. After victory in the War of Independence from Spain, the first Ecuadorian constitution was written and signed in Riobamba in 1830. As we drove through town, Roberta gave us the daily news: A drug cartel had been found in the country, causing a break in relations between Ecuador and Columbia. Columbian guerillas hide in Ecuador, facilitating drug trafficking between the countries. Roberto also reported that the southwestern provinces and all coastal villages had been flooded due to rain.

Feeling fortunate that we had not been affected by the rain, we continued southward to catch our “Devil’s Nose” train ride in the city of Alausí. We passed by a cement factory, one of four in the country. Farmers cultivated land by hand, while children worked on mini-plots. Most people in Ecuador are farmers. 30% of the population are indigenous, 60% mestizo and 10% of African origin. Indigenous people and trade unions were able to put the current president into office eight years ago.

Steaming fast-food carts lined the street in Colta, a small village which is home to Ecuador’s oldest church, built in 1534. People pumped water from a lake, while an Andean gull enjoyed the fresh waters. Meter-tall quinoa plants thrived at the high elevations. Farmers shake the plant to obtain its kernels, which are 18% protein and are cooked as cereal. Next emerged the Guamote Valley, which is divided into four areas, each specialized in its own field of production — potatoes, vegetables, fruits, or animals. Herders huddled in brightly colored ponchos and hats. Looking over and through the clouds, we passed the valley, finally arriving in Alausí.

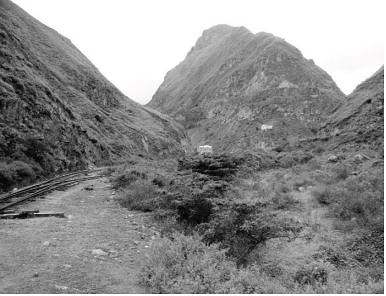

Approaching Devil’s Nose

A giant statue of Saint Peter, patron saint of Alausí, gazed over the city, partially shrouded in clouds at 7704 feet as we approached. Here we were to catch the train for our much anticipated descent of a rock face known as the Devil’s Nose. Originally we were to depart from Riobamba for this train ride, but due to washed-out tracks we started in Alausí, shortening the trip from 5 hours to 1½. While we waited for the train to arrive, I wandered away from the station to walk around town. A colorful group of indígenas crowded in front of the central bank, waiting for it to open. Others, prominent in their black fedoras, sat on benches in the town center. Girls in brown uniforms walked to school. A vendor caught my attention with his cabuya bags, made of fiber from agave cactus. Naturally, I had to have one.

Train travel in Ecuador began in 1910, when the Quito-Guayaquil line was opened with US technical and financial assistance, reducing to two days a former nine-day journey along a path impassable half the year because of rain. Due to its spectacular scenery, the most famed section of this journey is the Devil’s Nose, which starts in Alausí. An $8 round-trip train ride guarantees travelers an unforgettable experience.

As soon as the train pulled into the station in Alausí, we rushed in to secure our choice of seats. Unfortunately, sitting on the roof of the train, the customary way to ensure the best view, is no longer allowed. During the next hour and a half we made a precipitous descent, crossing spindly bridges over deep ravines via a switchback rail, alternately advancing and backing down the vertical rock face as the train followed the tracks, which zigzag along the slope. While the view was spectacular, any of the boulders could have tumbled down on the tracks, which were at times occupied by animals as they followed the edge of the ravine. The journey provided an adrenalin rush, especially when we went backwards to switch tracks before going forward again. This was an experience not to be forgotten quickly.

Our return to Alausí was followed by a very welcome lunch at a local restaurant — quinoa-and-potato soup, beef, potatoes with thinly sliced avocado, and flan for dessert. Then we were back on the bus for a four-hour trip to Cuenca through dense fog and stunning green vistas. Farmhouses with geese and horses, and laundry under protective plastic on rooftops, lined the road. It started to rain as we descended to Canar Province, home to wealthy farmers, as evidenced by multi-level brick houses with balconies and tile roofs. The owners were employed as migrant workers in the US and Spain.

As the sun came out, activity on the road and in the fields increased. Trucks carried cement and oil. Indígena women farmed in colorful skirts and white hats, waterproofed with pulverized corn to fill gaps in the wool. Traffic slowed down at a pig stop; Roberto urged us to descend from the bus for this discovery. We were at a rather unconventional roadside stand, where a woman was skinning a pig. Cascarita, torched pig skin, is a delicacy in the Andes. The crisp skin is served on boiled and salted hominy (white corn). Slices from a whole roasted pig are a popular snack. The owners of the family business we were watching kill and sell one 300-pound pig a day. Pork goes for $7 a pound or $3 a plate.

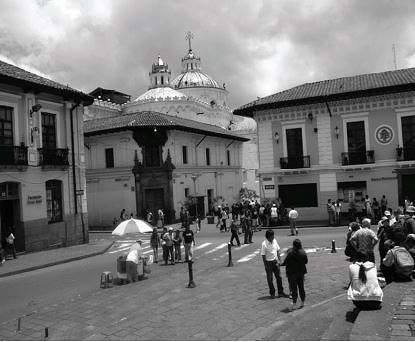

Basket vendor in Cuenca

The four-lane highway around Canar expanded to six lanes as we approached Cuenca, Ecuador’s third largest city after Guayaquil and Quito, with a population of 500,000. Densely built houses with tile roofs and brick apartment blocks crowded the mountain plateau. Passing a brick factory, we left the Pan-American Highway and took a perimeter road to reach Cuenca. Busy streets, traffic lights, and school children at bus stops signaled an urban core. Students attend school in either the morning or the afternoon session, which ends at 6 pm. Late 18th-century houses, many under restoration, overlooked the tree-lined river. Skillfully negotiating the narrow streets of this major colonial city, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, our driver pulled up in front of the Inca Real Cuenca Hotel, our home for the next two nights.

Built as a residence in the early 19th century, the two-story colonial Hotel featured an interior patio with a tile floor and potted plants. The spacious guest rooms opened onto the patio on the ground floor, and onto a balcony with a carved wood railing and hanging plants on the second. An elaborate wrought iron front door opened onto a cobblestone street. This door was kept locked at all times, except when the doorbell was rung. After a buffet breakfast on the patio, we strolled to the town center.

Enjoying whitewashed buildings with huge wooden doors and ironwork balconies, as well as a skyline dotted with church domes and towers, we arrived at a plaza overflowing with flowers and greenery. The Town Hall and Cathedral faced the plaza, which featured a flower market. People read the paper on park benches. Vendors of votive items crowded church entrances as many, including students in uniform, filed in and out for morning prayers. The top three professions in Ecuador are doctor, lawyer, and priest.

An excursion to the countryside took us to Chordeleg for lunch and a visit to orchid gardens afterwards. Turning off onto a rough country road, we arrived at the Hostería Ushupud, where we enjoyed lunch outdoors. Always preferring seafood when given an option, I chose shrimp ceviche, sea bass from Ecuador’s Pacific coast, “tree tomato” juice, and “three-milk cake” for dessert.

A guided tour of an orchid research center was a learning experience. Young orchids are kept in bottles with appropriate enzymes for a few months to aid their growth. During this time the plants are taken out of the bottles four times and checked for bugs. Then they go into small planters until they are big enough for outdoor planting. The gardens we visited had 4500 species of orchids — 2500 wild and 2000 hybrid.

The Cuenca basin is a center for artisans producing ceramics, Panama hats, baskets, and ikat shawls. We visited a weavers’ workshop for a demonstration of the production of hand-woven shawls, called macanas. In the ikat technique, fibers cut from plants are tied around the threads. The design is established by the number and size of knots on the threads before they are dipped in baths of natural dye, such as brown dye from walnuts. For a pattern to be added, the threads are tied and dyed again. In the final stage, the threads are stretched on a backstrap loom for weaving. I bought a shawl with red and black patterns.

In a Panama hat factory

A visit to a Panama hat factory was another discovery. Panama hats acquired their English name when supplied in bulk to workers on the Panama Canal, but they are made in Ecuador. The local name for the hats, sombreros de paja toquilla, refers to the toquilla straw they are made of. This is a natural fiber belonging to the palm family. We watched artisans weave and mold the fiber into hats. The fineness of the weave determines the value of the hat. Coarsely woven hats sell for under $50; fine ones, which feel like silk to the hand, sell for over $100. A straw doll was my only purchase.

In the evening, we went to a restaurant on the central plaza to try typical local food. Dishes the group sampled included egg drop soup, potato soup with melted cheese, beef topped with eggs (sunny side up), fried pork, stir-fried shrimp with vegetables, steamed tamale, and potato-and-avocado salad.

Cuenca is the intellectual and economic center of the southern Sierra, with a state university and many theaters and museums. The new Central Bank Museum sits above excavations of Incan walls. The pieces on display have been recovered from these excavations and include ceramic pots, ceremonial cups, anthropomorphic idols carved from sea shells, gold and silver pins to fasten ponchos or shawls, idols left as offerings at burial sites, and other pre-Colombian objects. An ethnographic collection highlights the cultures of inhabitants of the coast and the Andean foothills, as well as of the highland natives. The ruins on the Pumapungo archeological site surrounding the museum include mortarless Incan stone walls. Turi Hill has a panoramic view of Cuenca.

Lunch at a restaurant called El Maís on Calle Zarca rewarded us with its historic setting, dating from 1830. The building was furnished with local antiques and crafts; its charm was enhanced by hand-painted images of corn and birds over sponge-washed walls. As an appetizer we enjoyed quinoata, made of hominy, quinoa, butter, and cheese. Goat stew and rice garnished with sliced avocado, zucchini, and tomatoes followed. For dessert we had figs cooked in brown sugar and served with cheese.

Later on we transferred to the airport for our 45-minute flight back to Quito. In-flight refreshments included banana chips accompanied by our choice of tropical nectars. Back in Quito, I quickly packed for our return flight to the US the next morning and went out for a final stroll in the vicinity of our hotel. I had barely taken a few steps when a fanciful ceramic turtle caught my eye in the window of an artisan shop. I walked into the shop; much to my delight, it also had mazapán figures like those I had seen on the walls of our hotel in Riobamba. These brightly dyed bread dough figures of humans and animals, unique to Calderón at the southern edge of Quito, are dried or baked, and finished with a coat of varnish. They are placed on graves as offerings to the dead on the feasts of All Saints Day and the Day of the Dead. I was charmed by a llama decorated with pink roses. In addition, I bought a small bowl hand-painted in northern Ecuador, where artisans use human hair instead of brushes to create patterns of very fine lines.

Following dinner, Fulya and I went to bed early, as we had a 4:30 am wake-up call for our 7:40 flight to Miami. However, when we reached the airport, we found that our flight had been canceled, leaving us with three options — spending an extra night in Quito courtesy of American Airlines, going on standby for the next flight, or flying south to Lima on LAN Peru to connect to their Miami flight. Reluctantly, we chose the third option, to guarantee our return home on the same day. Dressed to go to Boston, we arrived in Peru, where it was 80º F. Feeling fortunate that we had had no similar delay on our outbound trip, we arrived home at midnight instead of 5 pm, as originally planned. Despite the unexpected detour at the end, we had a wonderful time in Ecuador, which left me with unforgettable memories.

Colonial Square, Quito