AMAZON BASIN

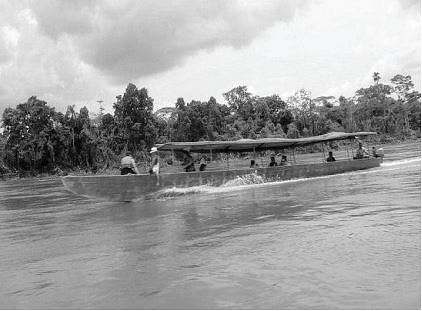

Motorized dugout

canoe ride

A 30-minute flight from Quito over the eastern slopes of the Andes took us to the town of Coca, deep in the jungle by the Napo River, the longest tributary of the Amazon. Along with the spectacular aerial view, hanging from snow-capped mountains to an endless green tapestry traversed by the sinuous river, the temperature rose to 86° F. Huge clouds drifted by, ready to dump their moisture onto the rainforest. In Coca, an open-sided minibus with a luggage rack on top took us to a boat dock, where we were fitted for jungle boots and donned life jackets for our motorized dugout canoe ride to the Yarina lodge, our home for the next three nights.

During the one-hour trip, our captain skillfully steered the canoe downriver, dodging driftwood in the murky waters, while Roberto, our naturalist guide, peeled his eyes to spot wildlife near the shore. Mangroves crowded the river edge, tall trees stretched toward the sun, and vines drooped into the water, multiplying in its mirrored surface. Shrill sounds of woolly monkeys filled the air, while stunning blue butterflies fluttered by. Parting with other boats, we turned into a canal to reach our lodge. The staff were waiting at the dock with hot washcloths and lemonade as a much needed refresher.

The lodge manager briefed us on the basic rules of the premises. There was no electricity; a generator operated from 6 am to noon and again from 6 to 10 pm. Battery-operated power was available for emergency purposes. We were to refill our water bottles from a supply of filtered water in the bar. All our valuables, bagged and identified with our room numbers, would be kept in the central safe. Following lunch, we would rest until 4 pm, since it was “hot enough to fry an egg outside” before then. We were asked not to enter our cabins with boots. Lunch was potato soup, followed by beef with a choice of steamed carrots, squash, and rice, and custard for dessert.

Our cabins were thatched roof huts on stilts constructed to withstand the extremes of the jungle climate; each had a porch with a hammock stretched diagonally across in addition to the hammocks in the main lodge. Despite the heat and humidity, a long-sleeved shirt, long pants, a sun hat, and rubber boots were my jungle wear for nature walks. Additionally, I wore a lightweight travel vest with multiple pockets to carry sunglasses, a camera, a spare battery, insect spray, and sunscreen. A water bottle bag with a shoulder strap kept my hands free to take pictures. During our nature walks, Roberto carried his telescope and tripod for close-up appreciation of wildlife. Two natives accompanied us to help spot wildlife.

Experiencing the rainforest through the eyes of a passionate naturalist was a very pleasant way to learn about the Amazon Basin and its unique ecosystem. Roberto spotted birds, tree frogs, lizards, squirrel monkeys, and flying turkeys on tree tops, bringing them within reach with his telescope. He took photographs by strategically placing my camera lens against that of his scope, thus enhancing the zoom capacity. True to his belief that “hearing is the way to seeing,” he followed high-pitched sounds to spot toucans, also locating a red-capped cardinal, a blue striated heron, and a white potoo. There are 400,000 species of tree in the rainforest. Competition among plants and trees for rain and sunlight is fierce. Only about 5% of sunlight penetrates the jungle canopy, so rain on the ground does not evaporate. Thus, two very different habitats for plants and animals coexist in a compact space. Trees do not like the clay soil and instead spread surface roots on the forest floor. Conditions at the very top of the forest, where cacti thrive, are desert-like.

Weaving a

palm-leaf basket

The following morning we observed the forest canopy from above by climbing 100 feet up a giant tree tower, enclosed by scaffolding supporting a stairway. To reduce weight, we climbed in two groups of eight. While one group ascended, the others watched one of our indigenous guides weave a basket out of palm leaves. Flowers and plants in the upper ecosystem love sunshine and never descend to the forest floor. No-sting bees, which looked like tiny black flies, swarmed around us, attracted to the salt in our sweat. Once we descended to the ground, there was no sign of these flies despite our increased sweat.

On our way back, we spotted birds’ eggs buried in the forest floor. Unfortunately, their camouflage had not kept predators away. Among the variety of mushrooms, the “one-day mushroom” was unique. Called “devil’s penis” by the natives because of its shape, this mushroom begins tilting as the day wears on, and is flat on the ground by nighttime. Other sightings included colony-dwelling spiders, leafcutter ants, and a wild juvenile tapir feeding on fruit leaves, which it grabbed with its trunk-like nose. Baby tapirs are born with a striped pattern, which helps camouflage them but fades away as the animals mature. Identifying a variety of palms used in making hats and baskets, as well as “vegetable ivory” used for buttons and decorative objects, completed our morning walk.

After a siesta our motorized canoe took us to an animal sanctuary, where we saw large land turtles and watched birds over the lagoon. Toward evening we paddled around the lagoons searching for caimans. They nest near tree roots and pile up leaves for camouflage to protect their young. Shining a flashlight into the reeds, we spotted two lying very still in the water; they stared back, eyes red with light reflected from their retinas. Although Roberto assured us that they were harmless, the vicious look of the reptiles discouraged me from using my camera flash. We paddled back through shimmering waters lit by glow worms, as tree frogs serenaded us.

Our visit to an Amazon village school was memorable. We arrived at the shore by canoe and walked through the jungle. On the way we learned about heliconias, which have red flowers, and balsa trees, which bear white flowers resembling little balls of cotton. We saw orange tamarin monkeys at a distance, and watched butterflies mate close by. Trees marked with orange ribbons identified areas of seismic exploration for oil. The discovery of oil in Ecuador in the late 1960s has since transformed the indigenous communities from quiet jungle dwellers into tough bargainers negotiating for land with oil companies, which also build roads. The country’s oil wealth is responsible for much of the work done to restore its colonial cities.

The children were in the school yard for the daily flag ceremony when we arrived. Eleven students, ages six to thirteen, including a four-year-old visitor, filled the one-room school house. The teacher, on his compulsory two-year duty to serve in a rural area after graduation, was being assisted by a mother responsible for breakfast. Six mothers take turns bringing breakfast to school every morning at 7 and staying on to assist the teacher, who commutes from Coca on his motorcycle. The class meets from 8-10:30 and again from 11-12:30 following recess. The children introduced themselves as customary in Ecuador, by mentioning their given name, followed by the last names of both father and mother. They sang for us and showed their books, provided by the government to standardize education. In response to our query as to their needs, we received a list; at the top of the list were notebooks, markers, and toothbrushes, all of which the group bought.

Afterwards, we visited an indigenous family from the San Carlos community. This young family with two daughters, one of whom we had met in school, offered us a drink made of casaba root which had been peeled, smoked, and left to ferment. We snacked on skewers of delicious roasted and salted gourd. The family grew everything they ate, and fished in the river, also used for bathing. They made handicrafts, such as gourds etched with local imagery, necklaces made of seeds, and wooden combs.

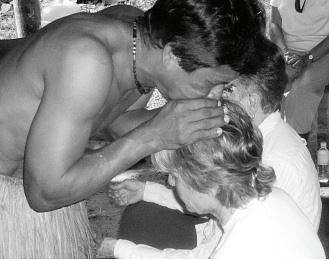

Fulya with healer

For the next cultural discovery we paddled to the hut of the local yachak to witness a healing ceremony. Wearing a grass skirt and red markings on his face, the 37-year-old healer told us about his training, which he had started at the age of two. His knowledge of medicinal herbs came from his mother and of healing rituals from his father; he was a third-generation healer and was, in turn, training his own son. He spoke of the healing process not as a way to eliminate bad energy, but as a means of balancing bad energy against good. To demonstrate his point he asked for volunteers, one of whom was my sister. With fans made of palm leaves, one in each hand, he began fanning with increasing speed around Fulya, who was seated with her eyes closed and palms up, ready to receive good energy. Then the healer smoked a cigar wrapped in a banana leaf, blowing the smoke over her head several times after inhaling it. He finished by fanning her again as he whistled. Completely relaxed, Fulya opened her eyes.

A cooking demonstration followed. We watched as a small piranha, including the head and bones, was chopped into bite-size pieces and marinated in a mixture of red onion, garlic, cumin, salt and pepper, and hot sauce made of peppers and “tree tomatoes.” This mixture was wrapped in banana leaves, tied tightly with vines, and cooked over hot coals. We enjoyed it with steamed manioc root, plantains, and “finger bananas,” kept in their skin and wrapped in leaves for cooking. Another delicacy was grubs, cleaned and skewered for roasting or steaming. Grubs, found on palm leaves, are full of palm oil, which drips away during roasting; they are quite delicious cooked in this way.

In the morning we woke up to the sight of a tarantula on the ceiling. Fulya, petrified that it might jump on her, asked me to wait till she dressed and left the room as I reached for my camera. In the meantime, the tarantula disappeared, much to my disappointment for the missed photo opportunity. After a breakfast of guava juice, scrambled eggs, and pancakes, we had a wonderful canoe ride down the lagoon, transferring then to a motorized canoe to reach Coca for our flight back to Quito.