TORTUGUERO

Tortuguero National Park is on the northeastern Caribbean coast of Costa Rica. To get there from San José, we had to drive through the usual rain and clouds on the eastern slope of Brauilo Carrillo National Park, as we had done before on the way to Sarapiquí. Early in the morning it was 55º F and visibility was limited to the trees by the roadside. Bumper-to-bumper traffic crawled through dense fog; impatient drivers tried to pass big trucks; cascading waterfalls roared beyond fogged windows. Finally signs saying “Bienvenidos a la Zona del Caribe” welcomed us to the Caribbean zone. The weather warmed up, people in shorts walked under large umbrellas, and signs advertized job opportunities.

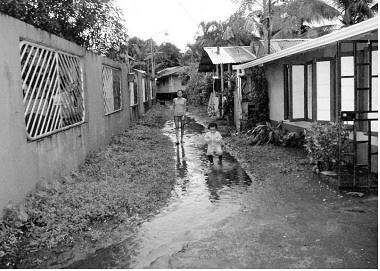

This was supposed to be the dry season in the Caribbean region, but it had been raining for days on end. We passed by homes with flooded yards, men and children with umbrellas on bicycles, workers with machetes clearing out grass around the banana fields of the Del Monte plant, and trees with bunches of bananas wrapped in blue plastic. Pablo promised a stop to visit the plant on our way back. On a gravel road turned into swampland, we drove through large puddles to the Caño Blanco dock, to board our boat for the hour-and-a-half trip to Tortuguero.

Alas, the dock was flooded. Our minibus could not reach the ramp since it, too, was partially under water. We rolled up our pants; some in water shoes, others in bare feet, we walked through flood waters to the dock to transfer to our boat. The crew carried our luggage, skillfully holding it up high above the murky waters. Stepping on a milk crate, we climbed into the boat. We cruised along, dodging trees which had toppled into the water and empathizing with cows herded away from the shores. Speeding on the inland canals, we became chilly after a while. With the wind flaps of the boat zipped up, the village of Tortuguero was an apparition as we passed by. Passing through a narrow, palm-ridged waterway six hours after having left San José, we arrived to welcome cocktails at Turtle Beach Lodge.

Remote Tortuguero, whose name means “turtle region,” is a nesting site for three kinds of endangered sea turtles — green, hawksbill, and leatherback. Therefore, their annual pilgrimage — at different times for each species, with hatching two months later — inspires much creativity among the locals. As we toured the grounds of the lodge, which was surrounded by beautiful gardens, we came upon a turtle-shaped swimming pool with a view of the Caribbean. Upon entering my rustic cabin with its ceiling fan, I found on my bed two towels folded like turtles with their heads sticking out — a delightful sight despite the rain. We were in a jungle by the sea with flooded nature trails and windswept, debris-filled beaches.

Exploring a river channel

Rain pounded through the night; the power went out for a while. At 6 am we donned green ponchos and went to explore the river channels. The water level, normally two feet, was up to nine; the channels, usually a little wider than a boat, stretched six feet on either side, submerging tree trunks. We were on a canopy ride by boat through various kinds of palm trees, where monkeys hid, and one-day flowers popped up despite the storm. The temperature had dropped as two back-to-back cold fronts gripped the region.

Village of Tortuguero

After a warming buffet lunch with soup at the open air restaurant of the lodge, we ventured to the village of Tortuguero during a pause in the rain. This mainly black village was Caribbean in character, with colorful houses and people. Mothers with children in tow walked down muddy paths without sidewalks or vehicular traffic; shopkeepers tended small shops crammed with goods; a juice vendor by the beach under her thatched stand, part of which had blown away, waited for a customer. The church, police station, and school, all sturdy and within walking distance, ensured essential services.

In keeping with the languid pace of our surroundings, we ambled on to the Turtle Research Center at the south end of the village. Our worthwhile visit here included educational exhibits and talks. We learned that turtles lay eggs by digging two holes between the shore and the grassy edge of the beach. One of the holes acts as a decoy to confuse predators, while the other incubates the eggs. A turtle can lay up to 100 eggs in two weeks. Since turtle eggs are a basic food source for many animals, as well as a delicacy enjoyed by people, only one egg in 100 survives to become an adult turtle.

The research center has a turtle adoption program for those who want to support its work. A turtle may be adopted in the name of a loved one for $100. The gift shop carries T-shirts, hats, bags, and other turtle memorabilia. I bought a crocheted bag with a colorful embroidered turtle design, made by a woman who worked for the center. Wending our way back to the dock, we stopped in a few of the shops, pleasing vendors, who depend on tourist income. North of the village is the river mouth, where waves break in the Caribbean. From the village we started up another river channel to return to our lodge in the national park.

In the morning we had to take an alternate route to go back to San José, as the one we had come on was flooded. It was still raining. Our luggage placed in heavy-duty plastic bags, we started on what was ordinarily a 20-minute boat ride, but took us an hour due to fallen trees on the channels. While our driver navigated his way around branches, we saw another boat with tourists viewing spider monkeys. We neared the shore for a glimpse of the monkeys, and spotted an armadillo as a bonus. Finally we reached the dock, and were relieved to see our minibus waiting. We quickly boarded it, happy to leave the monsoon behind.

On the alternate route, which took us through the town of Guapiles, we stopped by banana fields to make up for our missed visit to the Del Monte plant. Bananas are rhizoids and need to be planted in soil with plenty of water. Within two weeks the plants flower and are tagged to keep track of ripening periods. In nine weeks bananas grow inside the flowers in bunches weighing 60-80 pounds each. While they are growing, bunches are bagged in plastic to keep insects out. When the bananas are ready for picking, carreros (carriers) hook the bagged bunches onto a rail system connecting the fields to a processing plant for shipping. Undocumented Nicaraguan laborers make over 20 trips a day picking, lifting, and hooking the heavy bunches onto trams, which travel over roads and rivers. Banana fields are sprayed every two weeks throughout the year, and are depleted after 40 years.

Banana plant

Bagged bananas

on the rail system

Our return to San José after our two-week nature trip was a welcome change. Never in my life had I been in so many different climate zones in such a short period of time. We had traveled to five of the six different climate regions of tiny Costa Rica, experiencing muggy wetlands, both rainy and dry forests, windswept and idyllic beaches, and an unforgettable monsoon in Tortuguero. This had truly been a once-in-a-lifetime adventure trip.

Endowed with such beauty and variety, Costa Rica makes the most of its riches. Protected national parks constitute a great part of the country. Costa Rica is open to all who wish to live within its borders. 100,000 people from the US live in the lush Central Valley, partaking in the pura vida, literally the “pure life.” This phrase is a typically Costa Rican idiom meaning “everything is great.” May it continue to be true!