January 2010

Why go to Costa Rica? This small country has major attractions — beaches, volcanoes, and national parks teeming with birds and wildlife. It is a nature lover’s paradise. Besides its tropical bounty, it claims to have the best working democracy in Latin America. A peaceful country with no army, it boasts the highest literacy rate in the region after Cuba. It had been on my list of countries to visit for some time. With the incentive of no supplement for single room accommodations from Overseas Adventure Travel, I signed up for their “Most Affordable Costa Rica” itinerary.

Normally I do not travel during holidays. Upon arriving at Boston’s Logan Airport, I quickly realized that this would be my first and last such mistake. At 5 am on December 31, all of Latin America seemed to be returning home from visiting relatives. Loaded with Christmas gifts, passengers formed long lines to travel to Miami for connecting flights to destinations such as Caracas, San Juan, and San José. Fortunately, we were able to depart on schedule, thus avoiding a predicted snowstorm later in the day. Bundled up for Boston’s 20º F weather, I became three layers lighter when we reached Miami at 76º.

San José is one time zone to the west of Boston; adjusting my watch, I settled down for the next four-hour leg of my trip, which was seven hours long in all. San José Airport was crowded — apparently a daily situation because of the large number of visitors. It took an hour to clear passport control and customs. Although only 8 degrees north of the Equator, San José was cooler than Miami because of its elevation at 3000 feet. Temperature in Costa Rica is determined by altitude rather than season.

A van arranged by the local office of the travel organizer delivered me to the centrally located Clarion Hotel, 25 minutes from the airport. Although I had not slept since 4 am, I could not help noticing all the littered streets as we sped by. Claiming my key from Pablo Yee, our trip leader, I carried my welcome cocktail to my room, too tired to enjoy it in the lobby. I dropped off to sleep instantly; the sound of fireworks at midnight reminded me that it was New Year’s Eve.

Donning sunscreen and mosquito repellent, which are needed daily in the tropics, I descended to the breakfast room. Among the buffet offerings were a platter of fresh papaya, pineapple, and watermelon; scrambled eggs; and gallo pinto, a rice and bean dish that Costa Ricans eat at most meals. The sunny terrace beckoned, although it was too cool to sit outside without a jacket. After breakfast, our group of fourteen met with Pablo. There were changes to the itinerary since January 1 was a holiday. Although the San José city tour was deferred to the end of our trip, I will include it here.

Founded in 1737, San José, the largest city in Costa Rica, is also the capital. It is situated in the Central Valley, where 3 of the country’s 4½ million people live. High enough for an ideal year-round climate, San José is surrounded by a cluster of towns whose residents commute to work in the city daily, contributing to its bustling life and traffic. There are lush parks, residential homes decorated with iron grill windows, and garden walls topped with barbed wire. Government offices and banks give the city a modern skyline. Most museums and theaters are in the walkable central part.

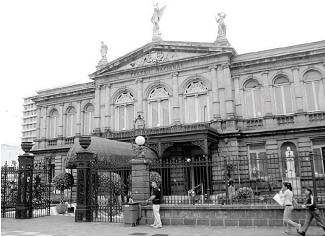

National Theater

The National Theater is an architectural treasure. Finished in 1897 with tax money from coffee exports, it is patterned after European opera houses. Its facade, overlooking Central Park, is Renaissance style, with figures representing Music, Fame, and Dance. Statues of Beethoven and of Spanish playwright Calderón de la Barca fill niches on either side of the entrance. The lobby inside has marble floors and columns. The grand staircase and foyer on the second floor feature Italian marble sculptures. The building’s only native material is its parquet floor made of Costa Rican wood.

Across from the Congress building is the National Museum, which features an excellent exhibition of pre-Columbian artifacts, some dating from 12,000 years ago. All of Costa Rica’s history and historical art are represented here, in buildings around a garden displaying imposing stone spheres several feet in diameter. Unique in the world in terms of size and spherical perfection, they are believed to have been made, starting in 300 AD, as territorial markers symbolizing high rank. The museum also has impressive displays of jade and gold ornamental objects.

From San José, we headed north on the Pan-American Highway in a minibus, riding through the Central Valley to Alajuela, where we stopped for lunch, viewing butterflies nearby. Casado is a typical lunch plate with rice and beans, which come with a choice of fish, chicken, or beef, accompanied by fried plantains and steamed vegetables. Soup and salad accompany most meals. Health and hygiene are considered a top priority in Costa Rica, where 97% of towns have potable water. We enjoyed raw salads throughout our trip.

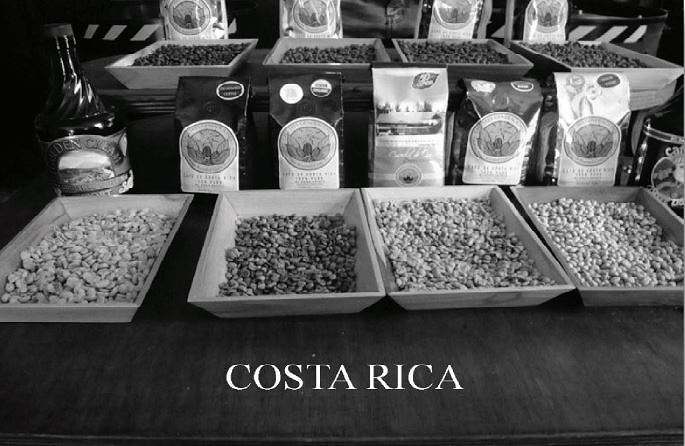

The day’s treat was a visit to the Doka Estate, a coffee plantation run by a third-generation family of farmers. Originally brought from Africa, coffee plants are first planted as seedlings. They are planted near shade-bearing trees to keep them from being scorched. Ripened red berries are hand-picked, mostly by Nicaraguan laborers, in baskets which hold 25 pounds. After the outer skin is peeled, the berries are floated in water and those that rise to the surface discarded. Fermented and sun-dried beans are roasted at temperatures of 15, 17, and 20º C, each temperature determining the mildness of the coffee, from house blend to French Roast to Espresso, the strongest. The biggest export market is Europe; sold as beans to Germany, coffee is bought back decaffeinated. Costa Rica provides 70% of the supply to Starbucks. Locals call this valuable crop the grano de oro, or “golden seed.” Oxcarts that once transported coffee are now colorful reminders of the past. Cities are adorned with gigantic bronze sculptures of coffee beans.

Crossing the Continental Divide, which separates Costa Rica’s rainy Caribbean region from the dry Pacific side, we entered Brauilo Carrillo National Park. Coffee plantations gave way to steep slopes and forests in the clouds. Downpours alternated with moments of tranquility, letting us enjoy waterfalls and the yellow, mineral-filled Rio Sucio. Our superb driver, Oscar, negotiated narrow roads with heavy truck traffic through torrents, finally turning off Highway 32 to Sarapiquí and the Trimbina Biological Reserve near Virgen; this was our home for the next two nights.

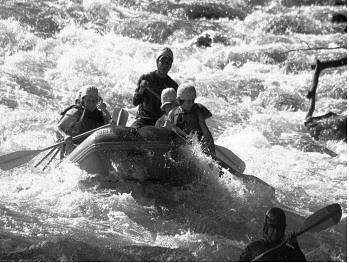

Rafting on the

Sarapiquí River

The Sarapiquí Rainforest Lodge is a group of indigenous-style huts with thatched roofs in a region known for 850 species of birds. At dawn, we watched birds feast on bananas put out by our tour leader, Pablo. Later, donning life vests and helmets, we enjoyed rafting on the Sarapiquí River. In groups of five, we paddled forward and backward and stopped, following our captain’s commands as we moved through almost still waters, as well as rapids with churning white peaks over rocks. During a shore break from our two-hour expedition, we learned about tiny poisonous frogs and tasted fresh coconut straight from the tree. A first-time experience for me, river rafting was a highlight of our trip.

Pineapples head the list of Costa Rica’s agricultural exports, which also include mangoes, bananas, and flowers. Belonging to the bromeliad family, which require daily water, shady soil with drainage, and stable temperatures, pineapples are best suited to the equatorial region. In a tented car pulled by tractor, we visited the country’s first organic pineapple farm, started in 1991. Plants grow through black plastic sheets laid down for weed control. Fertilizers contains no chemicals. Pineapple has to be stressed to come out; ethylene gas is used to have all the plants shoot up at once. Each plant yields ten shoots, one of which is replanted. 10,000 shoots are planted daily; workers are paid by the number of shoots they plant or pick, earning $35 a day.

After being picked, the pineapples are washed in water, with any soft or brown ones discarded. Then they are placed in boxes, weighed not to exceed 12 kilos, as the company is paid by the box. Labeled boxes are taken into freezer room at 45º for four days to ferment before shipping. The company is phasing out all but 30% of its organic production, as demand from the US has decreased with the recession. The major US buyer of the organic supply is Whole Foods. The Golden variety, developed in Costa Rica, is unique to the country; Brazil, where pineapple originated, is the world’s largest exporter. At the end of the tour, we sipped piña colada from fresh pineapples. Advice on how to select a pineapple at the market overturned existing myths. We are to pick green fruit with firm bottom leaves that resist when pulled. Leaves that pull out easily indicate fermentation due to excessive handling.

We had a superb lecture in the evening by a specialist on bats. 50% of the world’s bat population lives in Costa Rica, which has 300 species, including ones that eat fruit, insects, and nectar, as well as viper bats. These flying mammals are beneficial, as each bat eats 1000 mosquitoes per night. They also pollinate flowers, help forestation by dispersing seeds, and produce a natural anticoagulant. Seeing a variety of bats in expert hands was most enjoyable.

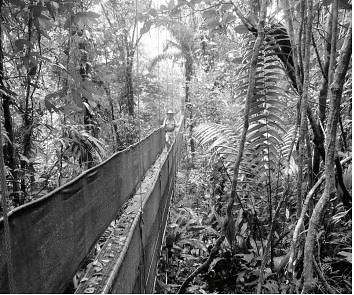

Suspension bridge in

Triamba National Park

Walking through Triamba National Park was a bounty of discovery. We crossed two suspension bridges — one over the Sarapiquí River, the other over the forest canopy. Rain forest trees have no age rings; trees long stunted due to a lack of sunshine shoot up as soon as they find an opening left by an existing tree toppling over. We gazed at “walking-root” palm trees, “monkey ladder” vines, pink and red ginger plants, and heliconias, while leafcutter ants trailed the forest floor.

Our discovery of the Sarapiquí region ended with a visit to the Anthropology Museum. Prior to Spanish colonization, this part of Costa Rica was inhabited by the Botos, an indigenous tribe. The museum has artifacts of their daily lives, including gourds decorated by scraping, pecking, and cutting; bags called chacaras, woven with purple fibers; and mastates, fashion items from painted cloth made from the bark of various species of tree, each giving a different color and texture. Leaves and roots are used to produce intense yellow, muted brown, deep black, or green dyes and paints, which are applied to create geometric patterns and stylized animal designs. The Botos were animists, and used herbal medicine and magical stones for healing. Near the museum are their burial grounds.