T I B E T

Rising at 5 in the morning, we caught a 7:40 flight to Lhasa, capital of Tibet at 12,000 feet. To adjust to the sudden change in altitude, we had started taking pills the day before. To shorten the red tape at the border, we traveled with only one carry-on bag each, leaving our suitcases back in Chengdu. Upon arrival, Susan obtained a special entry visa for us. It was thrilling to finally see the blue sky and bright sun for the first time since arriving in China. The clear, dry air and the majestic mountains in the distance confirmed that I was indeed in the place known as the “roof of the world.” It felt wonderful.

Soldiers in camouflage uniforms guarded the airport, 65 kilometers from Lhasa. Our Tibetan guide welcomed us in the name of Buddha and handed us each a white silk prayer shawl as we settled in our seats. He taught us a few Tibetan words — such as “tho qiu qiu,” meaning “thank you” — then gave us basic information — for example, that one tips toilet ladies in Tibet, unlike other parts of China. We passed by a large Buddha carved into the mountainside, fields of poppies, mustard plants, poplar trees on river banks, many greenhouses, and housing developments with traditional red doors. Chinese flags on buildings waved in the wind. Festival flags in five colors symbolizing the elements — white for clouds, yellow for earth, red for fire, blue for sky, and green for water — stretched across the main road; they were vestiges of a celebration two weeks earlier honoring the 40th anniversary of Tibet’s “liberation” by the Chinese in 1965.

Once at our hotel, we all drank plenty of water and took naps to chase away the effects of altitude change. I had a slight headache when I woke up, but felt fine after taking aspirin. A lecture by a Tibet University professor enlightened us as to Tibetan geography, history, religion, customs, and politics. The north is the largest and highest area, as well as the coldest year-round. The east, at 9000 feet, is the lowest, with forests and green mountains, where it is warmer and humid. This is the area where the Han Chinese have settled. The central part, at 9-12,000 feet, is the main agricultural region. It is also the hub of culture and religion, where the largest cities are congregated, including Lhasa with a population of 400,000. There are 4.9 million Tibetans in China; 2.7 million live in Tibet.

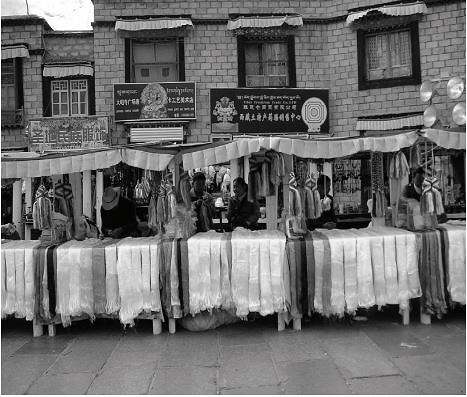

Stalls selling prayer shawls

Tibet is one of five “autonomous regions” in China. The regional government follows the laws of the central government, which controls entry into Tibet. The region was controlled by Tibetan nobles and the Dalai Lama until the latter left for India in 1959. “Dalai” means “ocean,” implying that the Lama is boundless; he was both the spiritual and political leader. During the Cultural Revolution in the 60s and 70s, many temples were destroyed. Now the practice of religion is freer. 90% of Tibetans follow Tantric Buddhism through meditation and prayer. Based on actions in this life, it is believed that one may go to heaven or come back, in descending order, as “denizen,” human, animal, or hungry ghost, or even end in hell.

The five funerary customs in Tibet are: stupa burial, reserved for the Dalai Lama, which preserves the body; cremation for the well off; “water burial” for commoners, whose bodies are wrapped and thrown into water; interment for the diseased; and “sky burial,” with a 3-day waiting period for body and soul to separate, followed by burning, powdering, scattering of the bones, and offering of the flesh to vultures.

The art of painting is an important part of Tibetan religion and culture. Thanka painting, formerly taught by monks, is now offered in the university art department. Thanka brings good luck; its images often depict a mandala (a square within a circle), the Buddha, and various bodhisattvas, representing long and healthy life. The biggest such painting hangs in the temple and comes out during the New Year festival. Smaller paintings hang in homes. At the end of her lecture Professor Nima presented each of us with a prayer wheel, like those initially used by people who could not read the scriptures. Hidden in the ornate body of the wheel is a paper prayer. The wheel is spun clockwise, the power of the prayer enhanced with each rotation.

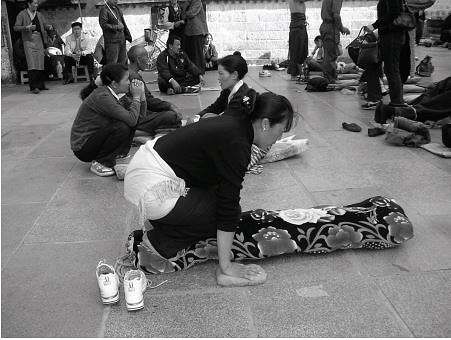

Pilgrims approaching Jokhang Temple

The Jokhang Temple, built to house the 7th-century Buddha statue of Jowo Sakyamuni, is the oldest and holiest temple in Tibet. Every Buddhist is expected to visit this temple at least once in his or her lifetime, to worship the founder of Tibetan Buddhism. Outside pilgrims prostrate themselves in reverence to the sacred site and move on their hands and knees to approach it. Inside thousands of yak udder candles flicker beneath the enlightened gaze of the golden Buddha as crowds press near. The khora is a clockwise circling of the temple, which is also surrounded by the Barkhor Bazaar, a series of shops and stalls catering to pilgrims and tourists. We walked clockwise through the market, gazing at jewelry, textiles, spices, and prayer flags, which carry written prayers sent to the gods with the winds.

A yak is a sign of wealth in Tibet. These horned animals with long, shiny black hair provide food, milk for dairy products, hair for awnings and blankets, horns for combs and jewelry, and tails for dusters. They also race during festivals. A big statue of two golden yaks shimmers in the sun in downtown Lhasa, which means “holy land” in Sanskrit. It was no surprise that our visit to a local family took place over yak butter tea, which we enjoyed in the sun room of a building that was home to four generations. After the milk is churned, the butter is mixed with water and salt, and then added to black tea with sugar. We sipped our tea as we nibbled on snacks spread before us — puffed rice and wheat, roasted peas and beans, dried dates, and cookies. On the way out we saw the meditation room with Buddha statues and a thanka painting.

A highlight of our trip was a visit to the private De Ji School for Orphans, which housed children from twelve days to thirteen years of age. Upon our arrival, the children greeted us by shaking hands, as each said “Welcome to my home.” We were hosted by the owner’s son, as the owner herself had gone to a monastery to have some newborn infants blessed. The children sang for us in English and took us by the hand to show us their dorms and classrooms. With a child at each hand, I saw the bunk beds where they slept together to keep warm, and then looked at the drawings they proudly pointed to hanging on the wall of the classroom. Walking me back to the bus, the children rubbed their hands against my cheeks in a downward motion, which is the customary way of saying goodbye. So moved by the warmth of these children, I was comforted to know that the Grand Circle Foundation, the charitable arm of Overseas Adventure Travel, supported their orphanage.

Dinner that evening was at a local restaurant, where we had a choice of a Chinese or Tibetan buffet. Opting for the latter, I was amazed at the variety of yak dishes, from dumplings to sausages. My favorite was yak yogurt, which had a rich creamy flavor. A folklore show with regional dances included masks, “yaks,” and herders.

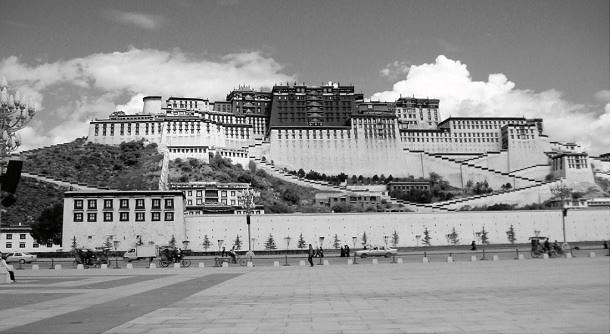

By now fully acclimated to the altitude, we climbed another 400 feet to the Potala Palace, the former residence of the Dalai Lama and the center of government. Perched on Red Mountain, it was built in the 17th century atop an original 7th-century site. This thirteen-story structure, boasting over 1000 rooms, is divided into the Red and White Palaces, with sweeping views of the city and the surrounding peaks. The richly decorated roofs of the palaces have glistening golden domes. We stood in front of the Dalai Lama’s balcony, where he used to greet people. We then visited his meditation room, a library for old scriptures, and the eight tomb stupas of the fifth to the thirteenth Dalai Lamas. Built as holders for souls and relics, such stupas are wrapped in pure gold. Protected during the Cultural Revolution, the Potala Palace possesses many riches, including objects studded with coral, turquoise, gold, and silver. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994, the location has a limit of 1200 visitors a day, including locals, who arrive with plastic bags full of yak butter to keep the chapel candles burning. We have a beaming group photo with the palace as a backdrop.

Our visit to the Sera monastery was yet another fascinating experience. Home to the largest Gelugpa sect, this monastery, which once had 7000 monks, now has 600. Built in 1419, it has three monastic colleges attended by aspiring monks, who come here after primary school and stay through retirement. As of 3 pm daily, monks gather in the courtyard to debate Buddhist philosophy. We timed our visit to coincide with this debate and were able to watch monks, including young boys, engaged in boisterous conversation. In pairs or in groups, monks in crimson robes settled down, with the questioner standing and the others seated, and began conversing, while also using exaggerated hand gestures indicating acceptance or rejection of a given response. While we did not understand what the monks were debating, their animated conversations were engaging to watch.

Potala Palace

Next we went to a printing house, where we watched a monk print scriptures on both sides of dampened paper using inked blocks. The originals were kept in cases behind glass. In one of the chapels, we watched another monk bless a seven-month-old baby by dotting its nose with black ink, rubbing its forehead on a stone in front of the Buddha, and then carrying it to several other Buddha statues for similar blessings. Our tour of the Sera monastery ended with a visit to the monks’ living quarters.

As a parting souvenir from Tibet, I picked up a small toy yak for my granddaughter Iris at the airport. Our Tibetan guide, Champa, bade us farewell with blessings from the Buddha. My window seat on the plane was next to a two-star Chinese officer. Shortly after we buckled in, the pilot announced that our flight would be delayed until he received clearance from the control tower, which turned out to be two hours later. My young seat-mate grew restless and began taking pictures with his telephone camera, first of the photos in the in-flight magazine, then of other grounded planes, which he could see from the window by reaching over me. Since we could not communicate verbally, he did not bother to ask permission. I gave up trying to read when he started to sing.

Finally, our 10 am flight took off at noon. We rose over Lhasa, surrounded by mountains cloaked in stubby green grass and by villages snuggled against them. The clouds appeared like puffed cotton under the brilliant sun, periodically revealing views of the snaking river below. Using gestures, my Chinese companion suggested I take pictures, which I did. Lunch arrived — yak meat with celery, green peppers, and rice.

← China (main page)