September 2005

On a beautiful autumn morning, I flew out of Boston for Shanghai via Detroit and Tokyo. I often worry about checked luggage when I have several connecting flights. I was reassured by the efficiency at Tokyo’s Narita Airport, as I cleared security and was ushered to the final leg of my Northwest flight. Once we were airborne, the Japanese flight attendants, all looking alike down to the parting of their hair, like a classical ballet corps, passed out three forms required for China — entry and customs forms, as well as a health card to identify passengers to be quarantined.

Going through immigration, I noticed a gadget that I took for a camera, but which turned out to be a thermometer. Aimed at my forehead, it checked my temperature. Relieved that the 24-hour journey had had no impact on my body heat, I walked out through the gates of the very modern airport into a mass of people waiting to meet passengers. I spotted my name amidst the sea of signs. A petite woman named Asa introduced herself as the guide for my tour. She informed me that the three others in my pre-trip group, all from California, had already arrived.

Shanghai’s Padong International Airport, 140 kilometers from the city center, is located on the eastern side of the Huangpu River and connects by a bridge to the old section of Shanghai. What used to be the vacant eastern side is now the new financial center. Steel and glass skyscrapers glittered in the night sky as we moved through the dense traffic. Although it was almost midnight and I had not slept for a very long time, I felt wide awake, caught up in the rhythm of the city. Shanghai, a city of 20 million people, never shuts down; there are 24 Pizza Huts and 30 Starbucks, as well as many KFC and MacDonald’s outlets, all popular. To help ease traffic, the municipal government each month auctions off a limited number of license plates, which are snapped up by wealthy people and foreign companies.

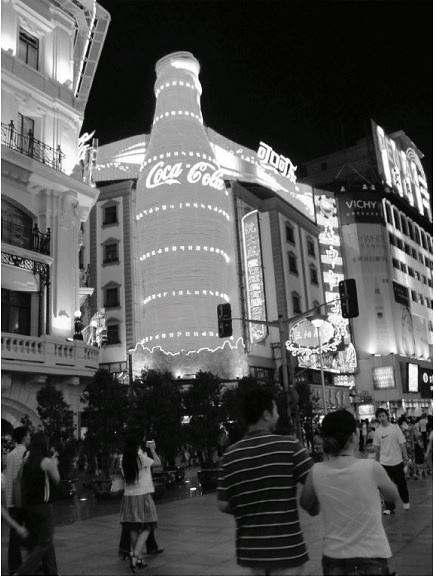

Nanjing Road at night

As the van approached our hotel on Nanjing Road, myriads of lights illuminated flamboyant skyscrapers, including one that looked like a pineapple. The vertical city seemed to pulsate with stacked up signs and large video screens advertising everything from cosmetics to Pampers. Green Sprite bottles lit from within lined both sides of the street. A gigantic Coke bottle donned in red created a street corner landmark. There was no doubt that Communism and capitalism thrived side by side in Shanghai.

Our small group of four met in the hotel lobby the next morning. We all appeared unaffected by jet lag and eager to start our adventure, although my body felt it was still 9 pm, rather than 9 am the next day. Our guide taught us our first Chinese words — “Nĭ hăo,” meaning “Hello.” We started at the Bund, a boulevard along the river lined with Art Deco villas, banks, and office buildings reflecting the European influence of long ago. The haze hanging over the city concealed a clear view of the new East, although we could sense the skyline pushing higher.

Visiting the Yu Gardens, built in 1557, introduced us to the ancient Chinese design principles of feng shui. The opposing forces of yin and yang are aligned in such a way that soft and hard balance one another. Plants pair with architecture, and water with rocks. Hard cobblestones complement wood structures. Generations of families watch over rock formations as they are shaped by nature, earning a living as “rock farmers.” Others sell crafts, food, and souvenirs to tourists and locals by leasing space in government-owned buildings. We walked around teahouses, pavilions, and goldfish ponds, and were bemused at the opportunity to buy cheap imitation Rolex watches.

Our treat of the day was a visit to a community center which served 90,000 workers living in nearby apartments. After a briefing by the director, we went to one of the homes for lunch. The owner worked at a car factory; he was not home. His wife, a sales assistant at a department store, cooked for us on her day off. She worked twelve hours a day, 3½ days a week. In China shops are open seven days a week year-round. The family lived in a two‑bedroom unit with their fourteen-year-old daughter.

Chinese dishes are served on a lazy Susan, starting with cold dishes, mostly pickled, and continuing with warm ones accompanied by rice. Soup comes before dessert, which is often fruit. Our menu consisted of dishes similar to what the family would eat on a festival day — quail eggs, roasted peanuts with seaweed, pork in thin slices of eggplant battered and fried, tomatoes with Mandarin oranges, pork dumplings, tofu with pork, baby bok choy, mushrooms, chicken with celery, shrimp, winter melon dipped in orange juice, pumpkin cake, and grapes. If it sounds like a feast, it was.

My new digital camera got a workout on its first day and had to have its batteries charged that evening. As soon as I plugged in the AC/DC adapter I had with me, it blew a fuse, leaving me in pitch-dark. Fortunately, I had packed a flashlight. I managed to locate it and called the reception desk for assistance. Right away I had the floor attendant at the door. I must not have been the first hotel guest to blow a fuse, as he did not even look surprised. Within ten minutes my lights were back on. To avoid future disasters, I resigned myself to using AA batteries, the price of which kept changing with each store. Bargaining for batteries was a new challenge.

A typhoon that hit the South China Sea brought gusty winds and heavy rain on our second day. Modifying our itinerary, we spent the morning in the new Shanghai Museum, a four‑story state-of-the-art structure. The top story is dedicated to arts and crafts of China’s ethnic minorities. Other galleries feature ancient Chinese jade, bronze, ceramics, seals, calligraphy, painting, sculpture, and furniture. These rare objects, created by the masters of each dynasty, are phenomenal collections, among the best I have seen anywhere. Each floor has a small shop featuring goods inspired by works in the adjacent galleries. Contemporary designers have drawn much inspiration from China’s rich history, as reflected in these shops and in the main shop on the first floor. Having spent the first of our two hours on the fourth floor and hurried through the remaining exhibits, I returned to the museum during my free time in the afternoon.

Lunch was a Mongolian barbecue — a buffet of raw meats and vegetables accompanied by a variety of pungent sauces, which we piled on our plates and carried to a cooking station. Stir-fried for us while we waited, this meal was more of a novelty than a fine culinary experience.

On the recommendation of two fellow travelers who had enjoyed a foot massage the night before, I decided to have one too. Going to the health club known for this required a stroll down the pedestrian section of Nanjing Road, by now in its evening glory. Computerized light patterns rushed up, down, and sideways on building facades. Chic shops glittered with stylish window displays featuring Caucasian mannequins. The pedestrian density was at its peak as people enjoyed shopping after work.

The “foot massage” turned out to be much more than its name suggested. A young man exhausted himself kneading, slapping, pulling, and pushing my limbs, back, and head for an hour. Because of the low cost of the massage, at only $12, I wanted to give the man a tip, which he declined. Tipping is not a custom at places for locals in China.

The next day, a 40-minute train ride to Suzhou gave us our first glimpse of the countryside. The two-story train passed by rows of young trees to be later transplanted to city parks, in addition to rice paddies, ponds for farming shrimp and freshwater crabs, workers’ apartments, and many shacks. As we approached Suzhou, there were more and more run-down buildings with laundry stretched across bamboo poles, as well as high-rise buildings. Suzhou is a 2500-year-old city with a population of 600,000 — a small city by Chinese standards. Until 1949, rich people lived here, because of the mild climate, and built elegant gardens and homes. Many of these were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution; a select number have been restored.

Classical Chinese garden

One such restored estate, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997, is the Master of Nets Garden. Laid out 800 years ago, the complex has a pond at its center, surrounded by roofed walkways and pavilions. Trees, plants, and rocks complement the architecture and the pond, based on traditional principles of design. As we walked around the living quarters, we admired the round windows — called “moon gates” — that framed the outdoors, making peonies, bamboo plants, and rocks appear as if they were finely executed landscape paintings.

Suzhou is a city of waterways connecting to China’s Grand Canal, which runs from north to south, where it meets the Yangtze River. A short cruise navigated us to the old section of town, where weeping willows and houses perched on stone foundations in the water lined the narrow canals. We also walked around the quaint streets on land.

The most fascinating part of the day for me was a visit to a silk mill. As a child in Turkey, I had raised silkworms in a shoebox, feeding them fresh leaves daily from the mulberry tree in our garden. However, I had never seen the process of obtaining silk from a cocoon. The harvesting time of the mulberry leaves determines the quality of the silk. Spring leaves yield the strongest and longest threads. We observed the life cycle of the silkworm from egg to cocoon, which is baked, so as not to allow the moth to cut its way out and damage the silk filaments. The cocoon is then boiled; this softens the threads, which are wrapped around spools, dyed, and woven into cloth. The mill shop offered a wide array of products ranging from quilts to clothes.

On our final night we went to the trendy Bar Rouge for a drink and a bird’s-eye view of the city from the rooftop. Lighting on all the buildings enhanced their architectural detail and highlighted the uniqueness of each high-rise spire, as if the structures were competing for first prize. Chinese characters on advertisements and lit riverboats added a pictorial touch to the nightscape. The spectacle before us celebrated Shanghai, whose people enjoyed making money and spending it with abandon.

Bumper-to-bumper traffic the next morning brought us southwest of downtown Shanghai to the historic town of Zhujia, known for its rice production. Here we enjoyed another beautiful garden. Built in the 19th century, the Ke Zhi Garden reflected European influence. Continuing to an exhibition hall on rice farming, we saw tools for flooding fields, harvesting, and storage. The importance of water buffalos to rice cultivation was evident from the displays. Another boat ride took us to the market in the old town, where we browsed ancient streets and traditional shops.

Among my memorable images of Shanghai are the many cranes along the skyline. The construction boom reflects the government’s strategy to make Shanghai the country’s financial center, surpassing Hong Kong by 2012. Entering China through this vibrant city seemed similar to arriving in the United States via New York. One may not choose to live there, but it is an exciting place to visit. After this grand introduction to China, we flew to Beijing on Shanghai Airlines to start the main portion of our trip.

Upon arrival in my hotel room in Beijing, I received a call from Susan Deng, our trip leader. She welcomed me in flawless English. She had learned the language in grade school and perfected her verbal skills at university under American teachers, who had called her Susan instead of her Chinese name, Ma. Susan traveled with us like a teacher on a school trip; she loved to educate us about her country, and watched over us to ensure that we were all happy and learning.

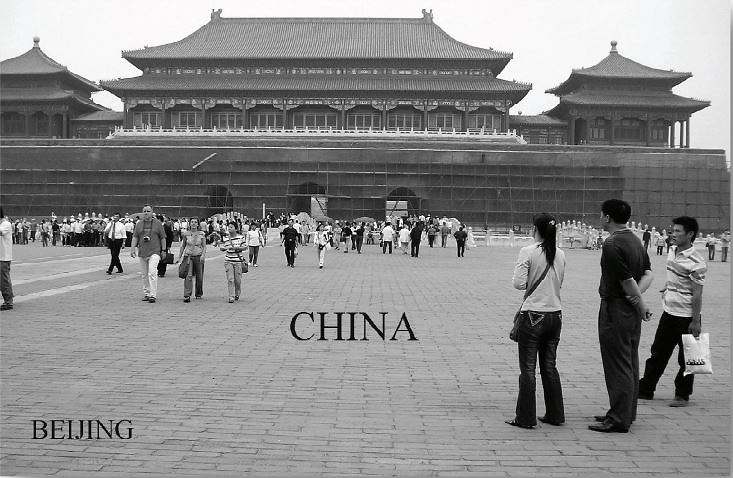

Beijing is the political and administrative center of China. It is laid out in concentric circles, the innermost being the Forbidden City, surrounded by the Imperial City. A giant portrait of Mao hangs over the Gate of Heavenly Peace, which opens out onto Tiananmen Square, the world’s largest public gathering place, holding over a million people.* Chairman Mao’s portrait presides over the Square, across from Memorial Hall, where the founder of the People’s Republic is entombed. Even though it was drizzling and a weekday, there were long lines of people waiting to pay their respects. A towering monument to the Heroes of the People — a granite obelisk honoring those who died in the Communist Revolution — is a prominent landmark of the Square.

* See postcard image at beginning of article.

As we walked about in the drizzle, we were surrounded by peddlers selling umbrellas, postcards, and trinkets. The square was populated by many tour groups, as well as workers. The latter were installing bleachers and flowerpots in preparation for October 1st — National Day, commemorating the founding of the People’s Republic, and the beginning of a holiday called Golden Week.

Much of the Forbidden City was under restoration during our visit. We walked about courtyards, admired ornate roof constructions with curved ends and fanciful corner structures with dragon motifs, and crossed over countless thresholds built to keep away evil spirits. According to folklore, evil spirits are tiny and cannot step over a low threshold. In the Forbidden City, where commoners were kept out for nearly 500 years, being a concubine to the emperor was a coveted position. One emperor had 3000.

How much of China’s lavish and exploitive history today’s Chinese think about is hard to know. But recent history has shown that things are changing. In 1949 Beijing had seven buses and 30 tramcars; now there are 300 new cars on the roads every day. Education is compulsory through ninth grade. In Beijing alone there are 80 institutes of higher education and 1400 high schools. Most of these teach English as a second language. Women and men work side by side for the same pay, whether they are street sweepers, construction workers, farmers, or office workers. 80% of people are farmers and make a living by selling crops to the state. Those earning over $100 a month pay 20% of income in taxes. They also pay for education, from kindergarten to university.

The New World Hotel, across from the New World Trade Center, was the setting for our dinner. We went to a restaurant specializing in Peking duck and other dishes prepared from duck. Through our local guide, we also had an opportunity to order personalized seals. We had a choice of either a jade zodiac animal, based on our birth year, or double dragons playing with a “pearl” carved out of “longevity stone,” which resembles brown marble. The buyer’s name is carved both in Chinese and in Latin letters on the bottom of the seal, which comes with a pad of red ink — red being the lucky color. I ordered a tiger zodiac, symbolizing protection, for my son, and a pair of dragons, representing longevity, for myself.

In the morning we visited the Bin Bin cloisonné factory, where generations of artisans have been practicing this popular craft for several hundred years. The elaborate technique involves hammering copper into a basic form and soldering curved copper wire surface decorations, which are then inlaid with enamel of different colors, fired several times, polished, and finally gilded. We tried our hand at glazing a few sample pieces, appreciating the patience and fine eye-to-hand coordination they required. Vases, bowls, jewelry, and other delightful items were available in the factory shop. I bought a bracelet.

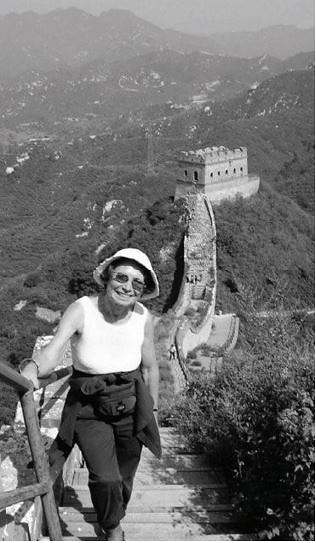

On the Great Wall

Afterwards, a trip to the Great Wall outside Beijing was most engaging. We traveled to the town of Badaling by bus, transferring to a van at the foot of the mountain. To reach the Wild Great Wall — the unrestored section, where there are no crowds — we went uphill on narrow dirt roads, passing by summer villas, a collision of two trucks, and trees planted to stop sand blowing in from the Gobi Desert. Then we began our climb of about 500 steps, stopping at times to rest and to take in the view. Seven out of our group of sixteen made it to the top — a great photo opportunity with the Wall snaking across the hills around us.

The Great Wall was built during the Qing Dynasty, around 221 BC, both to protect the northern frontier and to create a roadway for troops, arms, and food. It is a colossal feat of civil engineering, built by 300,000 soldiers and peasants from all parts of China, many of whom perished carrying rocks up the slopes. On the way back, it took us three hours to travel a 50-mile road due to traffic. We entered the city at the fifth ring, and finally made our way through noise and pollution to our hotel in the first ring.

On Saturday morning, our third day, we admired silk carpets at a factory, followed by a visit to a kung fu school. A private boarding school for elementary through high school students, the institution provides intensive training in martial arts in addition to academics. The students met us outside with a lion dance performance, and then ushered us into the auditorium for a demonstration of skills by age group. We watched them break boards on bare backs, shatter a plate using two fingers, and climb metal poles, to name but a few feats. They were all learning English and enjoyed talking to us afterwards. Founded by a monk in 1991, the school has 900 students, 98% of whom are boys. Students attend the school for a minimum of six years and aspire to become bodyguards, performers, or movie stars.

Our afternoon excursion to the Summer Palace, 20 kilometers northwest of Beijing, was delightful. The approaching Autumn Festival, the second largest after the New Year, combined with the weekend, created a festive buzz on the roads. Out of their bike baskets vendors sold “moon cakes” special to the festival and symbolizing family reunion. Wedding processions of cars decorated with flowers and balloons marked this as a lucky day for marriage. Red, the color of good fortune, dotted the cityscape.

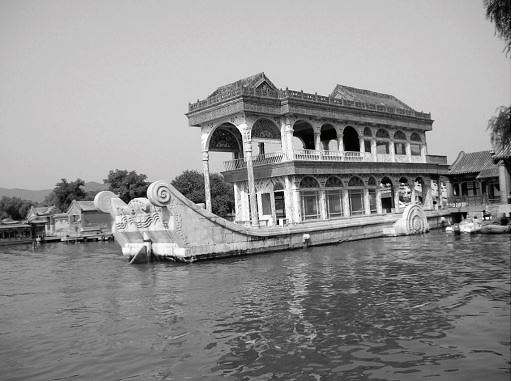

The Marble Boat

The Summer Palace — built in 1750, during the Qing Dynasty, in honor of the 60th birthday of the Emperor’s mother — is the largest imperial garden in China. Burned down in 1860 by the British-French Allied Army, it was restored and turned into a park after the last Qing Emperor, Puyi, left in 1924. Surrounded by Kunming Lake and classical gardens, the palace halls and pavilions are filled with ornate furnishings and fine artwork, including the Empress Dowager’s living quarters and the Long Corridor with its painted ceiling. The Marble Boat sits in the lake as a symbol of strength and stability. We enjoyed a dragon boat ride on the lake before departing for dinner and the Beijing Opera.

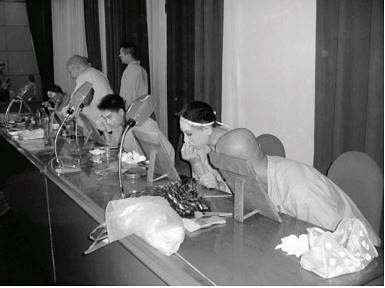

Make-up studio at Beijing Opera

Presented by our guide as one of the three musts of the capital, in addition to the Great Wall and Peking duck, the Beijing Opera began as cultural entertainment for court society. It combines songs, dialogue, mime, dance, and acrobatics, accompanied by Chinese instrumental music, including a lute, called the pipa, and a two-stringed fiddle, the erhu. Folk tales, legends, and classical literature inspire the plots, imperial dress the lavish costumes. Colors and intricate designs on the actors’ faces provide clues as to their character, age, and gender. For example, red stands for brave, blue for arrogance. We watched the actors paint their faces before a version of the opera shortened for foreign visitors, as the normal version lasts three hours without applause. I found the faces compelling, and could not resist buying a T-shirt displaying imagery from the Opera.

Our final day’s tour took us to Hutong, a government-preserved neighborhood of narrow alleys. We walked by 300-year-old homes built around quadrangles. This was a major restoration project, with builders at work seven days a week to finish it in time for the Olympics. A lively area with craft shops, the area is a teenage hangout at night. The value of the finished compounds has skyrocketed, attracting wealthy buyers.

We stopped for lunch at the home of a professional painter, who lived in an old home with his wife and teenage daughter. His studio was a sectioned-off corner of the small living/dining area. With a miniature rolling pin we rolled out small pieces of dough and learned how to make dumplings. After lunch we viewed the artist’s portfolios of traditional brush paintings on silk, as well as contemporary renditions. I bought a monochromatic landscape of varying green hues with two white cranes, signifying longevity.

Tea and conversation were at the home of an 88-year-old woman, who told us her story of growing up with bound feet. At the age of six, her mother had tied rags around her feet and sewed them tightly together so that they would not come off. She had lived with bound feet for ten years, and recalled how painful it had been. She had been sixteen when the custom had been outlawed and the rags had finally come off her feet; however, they had never grown to normal size. At 21 she had married an older man, who had died when she had been 30. She had remained a widow ever since, living with her daughter, who took care of her. Following dinner at a local restaurant, we headed to the train station for our 800-mile overnight journey to Xi’an.

The four-berth compartments of our train were equipped with paper slippers, a reading light, and a TV at the foot of each berth. Our group was able to travel in twos by paying for all four berths in each compartment. Otherwise we could have ended up with local passengers of either sex in the upper berths, as there is no gender distinction on such transportation in China. We checked our luggage and each kept a small overnight carry-on bag.

At dawn the scenery outside the window alternated among yellow, green, and brown fields, depending on the stage of the crops. Rice paddies were on slopes and corn on flat land, with some left to dry on rooftops. Farmers doing tai chi animated the fields, which were separated by rocks. The train speeded by brick huts with satellite dishes, old mud walls, workers on construction sites, and women with children on their backs. Gradually, brick and mud gave way to concrete and billboards. The number of relay towers for cell phones increased; trucks and cars populated the roads, adding exhaust to an already thick shroud. When I could barely detect tall buildings ahead, I gave up on the window view. The train attendant arrived to collect trash and our paper slippers.

When we arrived in Xi’an at 8 am, people were already returning from the early morning market. Most Chinese shop for food daily. We had to walk to our van, since the driver could not get near the station due to traffic. Susan cautioned us in crossing the street. “Road killers,” as those learning to drive are called, do not stop for pedestrians. Xi’an’s population is 7.2 million. A wall built during the anti-Japanese war divides it into an outer and an inner city, built on a symmetrical grid design. There is no subway system because of the historical relics underground.

Susan looked forward to showing us her hometown, where she had also attended one of 43 universities. Shortly after we arrived at our hotel, we participated in a tai chi demonstration by a master, followed by a visit to the Wild Goose Pagoda. 30 monks live in this 1100-year-old Buddhist landmark. People light incense sticks and place them in a bronze urn, sending their wishes to the gods with the rising smoke. 30% of Chinese practice some form of religion, mostly Buddhism.

In the afternoon the Sha’anxi History Museum introduced us to Xi’an’s past as the capital of eleven dynasties and a center of Chinese civilization. As we moved through China’s history, the artifacts reflected the dynasties’ growing wealth. One object that intrigued me was a “reverse-flowing pot” from the Song Dynasty. The handle of this teapot, carefully designed and crafted, is shaped like a flying phoenix, its mouth like a baby lion’s head. Water goes in from a small hole in the bottom and runs out the mouth without dripping when reversed. I was delighted to find a replica of this classical pale green teapot later in a shop.

The novelty of the evening was a visit to the Muslim Market, which was lined with shops and stalls, tended by vendors in white brimless hats. We stopped by a pharmacy that sold Western medicine on the left side of the shop, and Chinese herbs in little drawers on the right. We sampled dried persimmons, roasted chestnuts, sweet cakes, and sticky rice filled with bean paste. The market was very crowded. One person in our group was robbed. By the time she noticed that only the two strings of her bag were hanging from her neck, the culprit had disappeared into the crowd. We quickly left.

A Mongolian “hot pot” dinner topped off the evening. We each received a bowl of hot broth, to select and cook from the variety of meats and vegetables placed in the center of the table. We dipped each morsel into peanut sauce before popping it into our mouths. Watermelon, apples, and pomegranates completed this enjoyable meal. Before retiring for the evening, we walked by the musical fountain near the Pagoda. Dramatically lit jets of water, synchronized to Western classical music and Chinese pop tunes, bounced up and down and changed directions, entertaining the crowds.

Terra Cotta Army

On our way to the famed Terra Cotta Army, we stopped at a jade factory. Jade is China’s gold; jade bracelets are passed on through generations. Weight, translucency, sound, and intricacy of carving determine quality. Du jade is hard; jadeite is soft and translucent. Continuing, we passed coal mines, which are plentiful and provide 72% of China’s energy and fuel, in addition to causing pollution. A nice contrast was the sight of pomegranate trees, brought via the Silk Road. The pomegranate blossom is Xi’an’s official flower.

A farmer drilling to find water discovered the Terra Cotta Army in 1974. Pits with more than 6000 life-size soldiers, ranked in military order by their color-patterned armor, were uncovered in vaults at the entrance to the tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi, the first Qin emperor and unifier of China. We walked along the periphery of the excavations, which were roped off from the crowds. We were able to see the soldiers, with their unique facial expressions, modeled on live figures and buried for immortality. The farmer who made the discovery was on hand to autograph the book Qin’s Terra Cotta Army for us.

Over lunch we enjoyed a noodle making demonstration, and went on to the wholesale herbal medicine market. Among the selections were dead ants for arthritis, fried silk worms for upset stomach, a variety of nuts for shiny hair, and turtle shells to make soup for kidney ailments. Villagers cultivate the medicines to sell to pharmacies and hospitals. The government owns the market and rents the stalls. The common belief is that Chinese medicine takes longer to work than Western medicine, but has no side-effects.

Thousand Hands dance

Dinner at a dumpling restaurant and a folkloric show culminated our day. We sampled every imaginable kind of dumpling in different shapes and colors, including tomato with walnuts and peas. Billed as a Tang Dynasty show, the dances accompanied by live music were exuberant, and included the Ribbon Dance, the Terra Cotta Soldiers’ Dance, and a Buddhist dance called the Thousand Hands.

Lacquerware is one of China’s ancient arts. When we arrived at the local factory, we had to walk around a screen in front of the entrance that kept away bad luck and kept in good fortune. There is renewed interest in traditional Chinese furniture made of rosewood and lacquer. A piece of furniture takes 50 layers of lacquer, with drying time in a dark room after the first 20. Then it is hand-painted and/or inlaid with mother-of-pearl. The showroom had exquisite pieces. I purchased a small silk embroidery of the Yangtze River on silk cloth, displayed between two pieces of glass and framed in rosewood.

After our visit to the old city wall, dating from the Ming Dynasty, Susan surprised us with a visit to a model home complex in a recently developed area of Xi’an. A three-bedroom furnished unit we looked at was contemporary design at its best. It incorporated traditional motifs into modern aesthetics of simple clear lines. Bamboo grew in glass cases dividing the rooms; traditional flower arrangements graced the recessed walls. The bathroom floor was divided between wood slats around the sink and tiles around the bathtub. Similarly, the sunroom was sectioned off, with a floor of pebbles for houseplants and a wood floor for the sitting area. A balance between soft and hard, and between warm and cold, applied throughout the space.

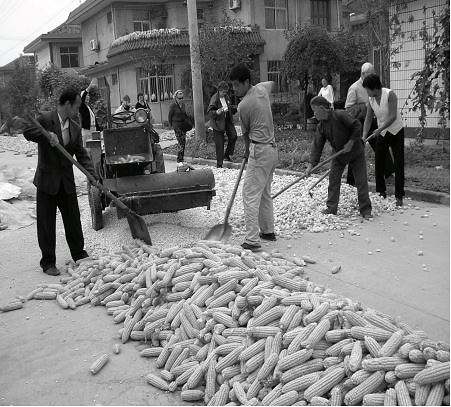

Hu Xian village

Another highlight was our overnight stay in the farming community of Hu Xian. Taking only hand luggage, we split into four groups of four to spend the night in this village of 900 people. Although our hosts did not speak English, we received a warm welcome upon arrival. Piles of yellow corn spread for shucking blanketed the asphalt road to our hosts’ home in the new section of the village, renovated and sold by the government. My group stayed in a two-story house where three generations lived — father, mother, daughter, and two grandchildren, a fifteen-year-old girl and an eleven-year-old boy. Village families are allowed two children. Those that exceed the limit pay a penalty of about $500.

The view from the terrace showed that the life blood of this village was corn. Corn lay on rooftops, hung from windows, and formed mounds in doorways. Our host’s house was spacious but sparsely furnished. Three bedrooms upstairs, where we stayed, shared one bathroom. The beds were hard but comfortable; flax seed pillows took some getting used to. Other furnishings were a TV, an electronic keyboard, and a loom. For supper we rolled beans, peanuts, and cauliflower in rice paper, followed by noodles in broth. Then we went dancing in the village square with women and children. Breakfast included congee (porridge) made of corn, flatbread with onion and vegetable filling, green beans, rice, noodles, and corn fritters, accompanied by green tea. Susan had advised us not to finish our plates, as this would indicate that we had not had enough.

Assuring our hosts that we were full, we strolled to the west side of the village to have a taste of the old countryside. We came upon a few bikes on dirt roads and many dilapidated houses. The once ornate front doors with guardian kings and good fortune signs showed their age through strips of peeling paint and mossy patina. Men harvested corn, while little children played in pants with split bottoms for easy squatting.

Hu Xian village is known for its farmers’ paintings and its folk art of paper cutting. Outdoor murals painted by farmers adorn many of the buildings in the new village. We visited the studio of Pan Xiaoling, a renowned folk painter and a leader among Peasant Artists. Her works are rich in color and depict scenes from villagers’ daily lives and traditions. I purchased one of the Lantern Festival. At another studio we had a demonstration of paper cutting. By folding and cutting a square piece of red paper, we were able to shape it into a pretty, symmetrical design. People who learn this art at a young age acquire amazing dexterity in creating intricate forms out of fine paper or silk. Loaded with weightless treasures, we returned to Xi’an to catch our flight to Chengdu.

Known as the City of Hibiscus, Chengdu is famous for its panda bears, Sichuan food, and teahouses, as well as Changing Faces, a virtuosic art of flipping facial masks in rapid succession. We experienced all of these treats but the pandas on our first evening. The delicious but spicy meal included lotus root, fish, rice cakes with pork, and a peanut dish. The teahouse was the setting for a Sichuan Opera and folk art performance. Waitresses came by with long spouted teapots, filling our cups as we waited for the show to begin. Earwax cleaning and massage for pay were among the options offered to the audience during the show, which included opera, puppetry, shadow play, clowning, and Changing Faces. Hand shadows transforming into a bird, cat, rabbit, horse, owl, and even two roosters fighting were delightful. Actors changing characters by flipping masks and spitting fire were magical.

Panda eating bamboo

Open to the public since 1995, the Giant Panda Sanctuary is a 90-acre natural habitat covered with bamboo. 30% of China’s pandas live here; the rest are in the wild. Pandas are born undeveloped and need a great deal of attention at birth, when they weigh only 100 grams. They walk at three months and have a life span of 25 years. They eat mostly bamboo. We watched pandas eat, sleep, climb trees, and play. Red pandas look somewhat like raccoons. Pandas are considered China’s national treasure. People who hunt them are sentenced to death. After President Nixon’s visit in 1972, the US received two pandas as a gift from China. On the way out I bought a panda hand-puppet for my granddaughter Iris at the gift shop.

On our return trip by bus to Chengdu, the views from the window of women weeding by the roadside, overloaded trucks, hundreds of bikes, traffic police and street sweepers in orange outfits in the haze, new apartments with penthouses and rooftop plants, a block-long Wal-Mart construction, statues honoring workers, and a colossal statue of Chairman Mao on a pedestal greeting people summed up this city of 4 million.

→ Tibet