March 2010

Our covered speedboat with panoramic windows took us to the border to clear Vietnamese and Cambodian passport control, which are a short distance from one another. Each checkpoint took 30 minutes to clear, giving us an opportunity to browse through souvenir shops while we waited. Vietnamese ingenuity stood out, with a fan which became a sun hat by joining the two Velcro ends. The Cambodian shop was impressive with its elegant handicrafts, whetting our appetite for what was to come.

On our boat with the national flag swaying in the breeze, we traveled upriver to Phnom Penh, passing villages with houses on stilts, skylines with pagodas and cranes for new construction, and shores fringed with fish nets and boats. At the dock, Thaly, our Cambodian guide, welcomed us with a big smile. It was 40º C, not unusual for Cambodia, which is hot year-round.

Riding to the Almond Hotel, our home for two nights, we saw signs of the glories and defeats of Phnom Penh. The riverside capital’s broad boulevards, named after kings, had taken on a run-down appearance due to long years of war and neglect by the Khmer Rouge. Hope, though, was in the air; new hotels and restaurants lined the banks. We passed the lotus-shaped Independence Monument, built in 1953 to celebrate freedom from France, which colonized Cambodia for 90 years starting in 1863.

Following a Cantonese lunch at the hotel, we visited the Royal Palace, located near the intersection of four rivers — the Upper Mekong, the Tonle Sap, the Lower Mekong, and the Tonle Basac. Built in 1866 in traditional Khmer style, with tiered roofs and topped by towers symbolizing prosperity, the palace has served as the official residence of King Norodom Sihanouk, the survivor of the constitutional monarchy, since his return to the capital in 1992. The residential quarter of the former king is not open to the general public; neither is the Royal Residence Compound of the current king, Norodom Sihamoni.

Dominating the center of the larger, northern section of the Royal Compound is the Royal Throne Hall, used for coronations, major constitutional events, and acceptance of ambassadorial credentials. The interior walls of the hall are painted with scenes from the Reamker, the Khmer version of the Ramayana.

Silver Pagoda

Near the North Gate is Wat Preah Keo, the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, which is also known as the “Silver Pagoda” because of its 5000 silver floor tiles, weighing more than one kilogram each. Disappointingly, all but a small corner of the floor is covered by a protective thick carpet, obstructing its grandeur. The temple, which has an ornately carved exterior, houses two priceless Buddha figures — the 17th-century Emerald Buddha, made of crystal, and the 90-kilogram pure Gold Buddha, encrusted with diamonds, the largest of which is 25 karats. The temple is considered to house the sacred symbol of the nation, so photography within the building is forbidden.

Dinner was an elegant affair at a Thai restaurant. A white napkin folded like a flower over the menu identified each place setting. The presentation of the five-course menu appealed to both eye and taste buds. The royal elegance of the palace lingered in many of the city’s restaurants, hotels, and shops.

The next morning’s trip to the Genocide Museum was a heart-wrenching experience, yet a must for all visitors to understand the extent of crimes inflicted on the graceful people of this gentle land. The former prison, known as “S 21” (Security Office 21), was the largest of 167 prisons created on the orders of Pol Pot. Once a school, the building was converted into a prison surrounded by double walls and surmounted by dense barbed wire. The classrooms were made into cells. Around 20,000 people perceived as supporters of the former regime, or Khmer Rouge officials who had fallen from grace, were interrogated here under torture and subsequently murdered with their families.

The museum was opened in 1979 to show evidence collected for a tribunal prosecuting criminal leaders. Among the exhibits are photographs, films, prisoner confession archives, torture tools, a list of prisoners, as well as their clothes and belongings. The bodies of fourteen victims, one female, believed to be the last killed before the regime fell, are buried in the museum grounds. The museum brochure states that “Keeping the memory of the atrocities committed on Cambodian soil alive is the key to building a new, strong, and just state.”

Mausoleum for Genocide Victims

A stupa-shaped mausoleum has been erected in memory of the victims in the Killing Fields, seven miles south of the city. On the way, we passed by slash-and-burn farms, fields of morning glory grown as cow feed, and houses with cows tied up front amidst trash. Even modern buildings alternated with junkyards; produce vendors spread their goods over a piece of cloth on the sidewalk, while police with mouth masks managed traffic. The river used to be the source of daily water until two years ago; with NGO and Japanese government help, running water now reaches all houses.

The Killing Fields are one of over 9000 mass graves discovered to date where prisoners were executed and buried. Many of these graves have now been exhumed; rows of skulls are arranged in tiers in a tall case in the middle of the mausoleum. Hundreds of folded origami paper cranes left by the Japanese Red Cross adorn the entrance. Bones and clothes are displayed separately in free-standing cases on the grounds.

As we walked about, we came upon a few tombstones with Chinese characters, indicating that this was formerly a Chinese cemetery. Chickens roamed about, pecking for food in the ground and unearthing an occasional human bone in the process. An estimated 1.5 million people died from execution, forced hardships, or starvation during the Khmer Rouge regime under Pol Pot from 1975 to 1979. Vietnamese troops invaded in 1979 and drove the Khmer Rouge to the countryside, beginning a ten-year occupation. The 1991 Paris Peace Accords mandated a ceasefire and democratic elections. A coalition government was formed; the constitutional monarchy, along with the palace, survived.

Phnom Penh has several large markets. We visited Psar Toul Tom Pong, the “Russian Market.” The name refers to the time from 1979 to 1993 when Russians, along with Vietnamese, were in the country and enjoyed shopping here. The market has several wings lined with hundreds of shops, which are crammed with anything locals might need — clothing, bags, jewelry, silk, curios, souvenirs, and a wide variety of dried and fresh food. Tailors measure and sew outfits quickly or do repairs while people shop.

At one time Khmer silk was considered to be among the most intricate and delicate in Asia. This once prosperous occupation was, however, destroyed during the Khmer Rouge period. Fortunately, silk farming and weaving have recently undergone a revival. New designs, combined with traditional workmanship and inspired by ancient patterns, are now coming onto the market.

National Museum

Behind a small public garden is the National Museum, which is housed in a red pavilion built in 1918. The museum is prized for its impressive collection of some 5000 objects of Khmer art, some made from stone said to be the finest in existence, though none may be photographed. Exhibits include a 6th-century statue of Vishnu, a 9th-century statue of Shiva, and a damaged bust of a reclining Vishnu, which was once part of a massive bronze statue found in Angkor Wat.

In the evening we enjoyed a sunset cruise on the river. The captain’s wife and daughter accompanied us on the boat. As the sun went down, pagodas silhouetted the shoreline, while lights on other buildings came on randomly. Afterwards, we paired up for a ride along the boardwalk and through the town in a rickshaw, called a remok. The night view of Phnom Penh accentuated its monuments. Lit up against the night sky, the Lady Penh Monument paid tribute to the city’s namesake; Phnom Penh means “City of Lady Penh,” an early benefactor.

Phnom Penh shoreline at dusk

Delivered by remok to a nearby restaurant, our buffet dinner was an overwhelming array of Asian food, which ranged from grilled prawns and fresh salads to more exotic fare, such as stir-fried morning glory stems. The place buzzed with activity, as tourists and locals moved among the many stations crowded with food alien to the unaccustomed eye. The spread included a variety of beef, pork, chicken, duck, fish, and soup dishes. In Cambodia soup is served as an accompaniment to main courses, not before them as in the West. There are three Cambodian restaurants in and around Boston, run by a couple who were forced into exile by the Khmer Rouge takeover. They have also produced The Elephant Walk Cookbook, an adventure into Cambodian cookery.

On the way back to our hotel we passed by a Kentucky Fried Chicken making its mark with prominently lit signs in this city, which appears to be racing into a market economy. Based on my observations of speedy development in Phnom Penh, I looked forward to the next leg of our trip, to Siem Reap, which I had visited five years earlier. Would I recognize the city?

Another local guide, Sang, joined us for the trip to Siem Reap, 195 miles northwest of Phnom Penh. The overland journey across the plains took us eight hours, with numerous stops at points of interest. Though the road was paved, our pace was slow because of speed limits, giving Sang the opportunity to talk about the changes that had taken place in the last 20 years.

Cambodia defines itself as a multi-party democracy under a constitutional monarchy. The king ratifies laws, but has no power to rule; his role is mostly humanitarian. Three leaders — the Prime Minister, his Deputy, and the Speaker of the 124-seat Parliament — rule the country. Each parliamentarian, representing 20,000 people, is elected to a five-year term. Over 50% of the population are under 20 years of age; therefore, only 8 of the 14.5 million are eligible to vote. In the last election, in 2008, the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) received the majority of votes among the eleven participating parties. The CPP, while providing the stability of one-party rule, has limited freedom of expression and banned demonstrations.

Lotus field

Traveling through the rural landscape, we passed by lotus ponds, rice paddies, tall haystacks, cows in brown fields, heaps of pumpkins, chili peppers spread on straw mats, shacks with hammocks, and sugar palms, as well as banana, cashew, coconut, and mango trees. We stopped at a local market to buy a lotus plant, carefully selecting one without any brown leaves, as the fruit is eaten before the leaves turn brown. In Buddhism different states of mind are compared to different levels of the lotus plant. One is asked, “Are you above the water, blooming like a lotus, or are you in the mud?” Buddhism is the state religion in Cambodia. Ancient temples are visited by pilgrims or tourists. There is a new temple for every two or three villages; communities raise funds to build their temples, which are mounted on stilts and covered with tile roofs adorned with Naga tails. In Khmer mythology, a many-headed, hooded water snake called Naga is believed to control the rains and bring prosperity.

In the market we also enjoyed roasted lotus seeds. Other local delicacies sold were tarantulas and crickets. Dipped in a batter of flour, garlic, sugar, and salt, they are deep-fried and sell for 25 US cents each in the case of tarantulas, 50¢ for 30 in the case of crickets. Tarantulas are dug or pulled out of their holes with an instrument and killed by having their stomachs pressed. Attracted to light, crickets are trapped by suspending a sheet of plastic over a pool of water, so that they fly into the sheet, fall, and drown. Locals eat almost anything available, including grasshoppers, banana and silk worms, lizards, and cobras. The latter go into whisky bottles for good eyesight, energy, and similar benefits.

Walking by a grove of cashew trees provided another discovery. The cashew nut grows on the outside of its red fruit, which resembles a small apple. Most of this produce is shipped to Thailand for processing, though we did taste some delicious cashews processed in Cambodia. The country is also rich in rubber. It was Cambodia’s plantations that attracted the French, who were competing with the British to colonize Indochina.

The “Stone Carvers’ Village” near a quarry had many stalls displaying sandstone works in various shades from beige to gray. Here I bought a figurine of Apsara, a mythical celestial dancing girl. At the “Brickmakers’ Village” we were greeted by many children and guided to a mud oven, where bricks are loaded and sealed for three days to bake. We distributed durian-flavored cookies as treats to the children. A lunch stop by the lakeside was delightful, with coconut juice served in its green shell, accompanied by an ample spread of pork with ginger, fish and chips, beef with fried eggs, noodles with vegetables, and stir-fried vegetables. For dessert we enjoyed pomelo, a type of fruit resembling a grapefruit.

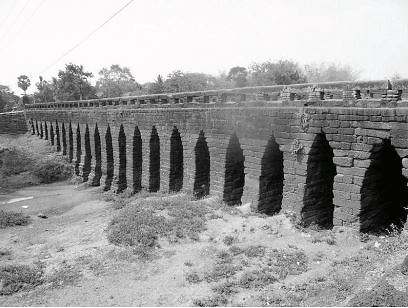

12th-century bridge

Entering Siem Reap province, which has a population of one million, we walked over the country’s oldest bridge, which dates from the 12th century, the Golden Age of the Khmer Kingdom. In Kampong Keidei, Sang’s native village, we passed by a temple, catching a glimpse of a Buddhist celebration. Sang introduced us to his family including his 77-year-old father, who was half Chinese and half Cambodian. After enjoying tea and cookies with them, we toured the garden, learning about the kapok tree, which is a source of income, as it is used to make fillings for cushions.

Farming and fishing provide the villagers’ livelihood. The government has given each family two hectares of land, which is in turn sold to agricultural companies. There is no electricity or running water in rural areas. People use oil lamps and run their televisions on a generator. They collect rain water or pump water from a well. Trash is either burned or buried.

Continuing northward, we drove by cricket traps, photographs of government leaders on billboards, motorbikes loaded with haystacks, people atop rice sacks heaped on carts, and cows — some in trucks, others on foot. Eventually, the rural look gave way to notices of apartments for sale, a modern home appliance store, a bus station, and finally the city of Siem Reap. In the five-year interim since my first visit the city had taken on a moneyed look, with many large new hotels because of the booming tourist industry. It had grown by leaps and bounds to keep pace with visitors, who fly in directly from Bangkok to see nearby Angkor Wat.

Siem Reap is a bucolic town of 300,000 people. Capital of the province by the same name, it lines the banks of the Siem Reap River. Sending our luggage ahead to the Tara Angkor Hotel, we visited a shop called Artisan d’Angkor and reputed for its quality handicrafts. Wood carving is a local specialty; teak, rosewood, and mahogany are the woods most frequently used. The shop had exquisite silk, as well as silver and lacquerware. Here I bought a lacquer wall plaque of a zodiac sign painted in gold, an ox-shaped silver box traditionally used for betel leaves, and a carved soapstone Apsara.

The Tara Angkor Hotel, which excelled in service and comfort, was our home for three nights. Its pool and state-of-the-art spa rejuvenated our weary bodies. A pedicure at $15 was irresistible. We enjoyed dinner at the Khmer Mondial Restaurant to the accompaniment of a traditional dance performance. Court dances in elaborate costumes alternated with folk dances where baskets, coconut shells, and fish traps were used as props. These beautiful dances enhanced our anticipation of what was to come.*

* See postcard image at beginning of article.

To have an impression of present-day Cambodia, we visited the nearby village of Krowarn and the Karmat primary school. The two-room schoolhouse accommodated 100 children aged six to thirteen (50 per room) — first and second-grade students in the morning, third and fourth-grade in the afternoon. The classroom had photos of the king and his parents, the former king and queen. The children put on a performance of traditional Cambodian dance, showing the intricate hand gestures they learn at a young age. We also visited the school library and read with the students. A thirteen-year-old, who took me around, gave me a drawing of her house, depicting a building on stilts and shoes left at the entrance. I was charmed by the details in this picture, as no Western child would have drawn shoes left at the door.

For our home-hosted lunch we bought ingredients at the outdoor market, each of us using an assigned Cambodian word; mine was the word for “garlic.” Our host, a 27-year-old woman, had been to the morning market earlier to buy fish, meat, and vegetables to prepare for us, as lack of refrigeration requires daily shopping. Her chauffeur husband was at work, her year-and-a-half-old baby at her mother’s house. She made a delicious multi-course lunch, which was topped by a sticky rice dessert we helped wrap in banana leaves. Admiring our host’s traditional silk shirt with its Chinese collar, I asked where I could acquire one like it. She called her sister, who sold such items at the market, and had her bring one to me. Unfortunately, she did not have the color I wanted; I ended up buying the shirt our host was wearing.

Basket weaver wearing

traditional krama

At the crafts village we watched women and children weave baskets, bracelets, and flowers out of palm leaves dyed in vibrant colors. 932 people lived in this village, under the watchful eye of an elected village chief. Among the weavers was a distinctive 61-year-old nun with shaven head and no teeth. Some of the women wore the traditional krama — a versatile, checkered, scarf-like head wrapping unique to Cambodia. A young boy befriended me by presenting me with a bracelet and flower he had made. In addition to these, I bought a few baskets as souvenirs.

While the rest of my group toured the famed temple complex of Banteay Srei, eighteen miles northeast of Siem Reap, I opted to visit the new Angkor National Museum. I had seen Banteay Srei during an earlier visit, and would recommend it for its fine pink sandstone carvings and the meticulous detail of its classical Khmer statues from the second half of the 10th century. Banteay Srei, which means “Women’s Citadel,” has shrines dedicated to Shiva and Vishnu. The main themes of the elaborate carvings are from the Hindu epic Ramayana. Buns, loosely draped skirts, and jewelry characterize the female divinities, lances and loincloths the male ones.

The Angkor Museum provides insight into ancient Khmer civilization. Exhibition galleries are reached by walking along a spiral ramp of the Atrium Hall, at the center of which is an immense statue surrounded by a garden. The Museum Shop offers high-quality Cambodian arts and crafts, including signature items.

In the evening I rejoined the group at a French-Cambodian restaurant called Les Orientalistes. The set menu included banana pancakes as an appetizer and sweet potatoes in coconut milk for dessert. While some in the group left for the French Quarter to get a taste of the city’s nightlife, I returned to the hotel in anticipation of our adventure to Angkor Wat early the following day.

In the morning we departed from the hotel at 7:30 to beat the heat and the crowds for Angkor, the capital of the Khmer civilization, which ruled from the 9th to the 15th centuries. The current King of Cambodia, Norodom Sihamoni, and former King Norodom Sihanouk, who returned from exile in Beijing in 1993, come from a line of monarchs going back to the “God Kings” of Angkor. Rediscovered in 1859, Angkor was neglected until 1992, when it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Most of the antiquities here escaped the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge campaign, which sowed terror and destruction throughout the country from the 1970s to the 1990s.

Stone gods at

Angkor Thom

Our tour of the vast complex, sprawling across 96 square miles, started at Angkor Thom (the Great City), surrounded by a wall and moats, which were part of the system of canals and reservoirs designed to control the seasonal deluge and to capture water for later use. We walked down one of the five causeways leading to the gates between two rows of huge stone figures — one row of 54 gods and one row of 54 demons pulling a giant snake on their knees. We then proceeded to Bayon, a grand temple with a four-faced statue of Buddha symbolizing equanimity, kindness, compassion, sympathy, and love.

Following a visit to the Hindu temple mountain Baphoun, we proceeded to the Elephants’ Terrace, where bas-reliefs depict almost life-size elephants. This structure was used as a viewing gallery by the King.

Next we went to the Terrace of the Leper King, where countless intricate carvings portray court attendants and rulers. This building was a royal crematorium. Stones were brought from a quarry by boat and carried to the site on elephant back. They were then stacked without mortar and carved.

Our five-hour morning tour ended at the Temple of Ta Prohm, ancestor of Brahma; the temple has been left the way it was found, covered by a dense jungle of trees and roots. Then we returned to the hotel. On the way, we saw locals draining water out of ponds with buckets to catch fish, which could not swim away without water. After lunch and a brief rest, we headed to Angkor Wat, the world’s largest religious monument and the masterpiece of the temple complex. This Hindu temple is dedicated to Shiva.

Celestial Apsara relief

We walked on a cobblestone causeway toward five conical towers representing Mount Meru, center of all physical and spiritual universes, and home to many gods in Hindu and Buddhist mythologies. The towers are surrounded by a moat 570 feet wide. Monks in saffron robes dotted the stone landscape. Wearing long pants with our shoulders covered and hats off, we climbed the steep stairs of the newly opened central shrine. At the top, celestial Apsara reliefs on columns surround a sunken open area.

After our descent, we entered the central sanctuary and admired the elaborate stone carvings along the surrounding wall portraying scenes from the Mahabharata. One of the most impressive carvings was a depiction of the Churning of the Ocean of Milk, a Hindu creation myth. A huge panel shows 88 devils on one side and 92 gods on the other stirring a sea of milk with a great serpent to extract the elixir of immortality. Overhead are singers and dancers, each with unique dress, hairstyle, and decoration.

Giant strangler fig

Equally impressive were the roots of giant strangler fig trees pushing through the surrounding stone walls. These roots have become so much a part of the building structure that they cannot be removed without causing the walls to collapse. Photographing this amazing symbiotic relationship of trees and stones, without hundreds of visitors posing in front of them, was a challenge.

Walking back on the causeway to catch the sunset, we settled onto a wall near the moat. Snacking on crispy frogs’ legs, beef jerky, and salted peanuts with homemade rice wine, we watched the Angkor towers become silhouettes as the sun went down. As we departed, vendors lined the roadside, selling snacks of sticky rice packed inside hollow bamboo and sold by the stick. Mostly used for sweets, sticky rice is farmed separately from regular rice, which is the basic staple. Cambodians do not eat much bread except for occasional baguettes, which the French introduced during their colonial rule in Indochina (Cambodia, Laos, and Viet Nam). Vendors sell baguettes in baskets or on carts along traffic-heavy roads.

Towers of Angkor

On our last day we traveled by oxcart to a local village south of Siem Reap to observe a day in the life of a rural community. Our group of fourteen split up and mounted seven carts, as each held two passengers. We entered the village on a dirt road lined with huts, some looking very modest and others more upscale. Here most people made their living as rice farmers. After our farmer host unhitched the two oxen on our cart from their yoke, he handed them over to his brother for feeding. Then he introduced us to his family. We walked around the spirit house to go upstairs and entered a large room built on concrete pillars. The room served as living room and bedroom. There were wedding pictures of family members on the wall, and mats serving as bedding neatly stacked in a corner. The ground floor was used for rice storage. The family also raised crocodiles for their skin.

Our excursion south continued by boat to Tonle Sap, which means “Great Freshwater Lake” and is the largest freshwater lake in Southeast Asia. It expands to four times its size during the rains in June and July. Flooding begins when the lake’s main outlet, the Tonle Sap River, reverses its course to flow north into the lake, causing its dwellers to move their homes up to fifteen times a year. The lake and its flood plain are vital to the country’s rice farming and fishing. A seasonal wetland for migrating birds and other wildlife, the area is recognized as a UNESCO biosphere reserve.

We visited a fishing village, one of 170 on the lakefront, where daily life glides by on the water. In this village of 3000, people lived in floating thatched houses on hollow bamboo poles, some with their own gardens and guard dogs, and all with TV antennas. Our boat followed a fairly wide main thoroughfare, with narrow passages between houseboats and extensive fish traps. The lake is a sanctuary for birds and home to 107 kinds of fish; yet it is not deep. The boats’ propellers churn up rich silt, spewing pieces of brown sediment into the air. On our route we passed women selling fruit and vegetables from a sampan, fishermen selling their catch, and naked boys enticing tourists with snakes wrapped around their necks. Other points of interest were a floating market, a Catholic Church, a community center, and a school where children arrived by rowboats, the older ones transporting the younger ones. During recess they bought snacks from vendors who arrived by boat. Children in neat uniforms rowing themselves from their houseboats to school were memorable images. At the end of this visit we transferred to the Siem Reap Airport for our flight to Bangkok.

Fishing village

During our time in Cambodia we gleaned a good idea of the country and its people. Having worn down the Khmer Rouge and broken their power, the nation is calm under a constitutional monarchy. Its economy, which was virtually destroyed, has moved away from Communist ideology toward a market economy. Presently the greatest sources of revenue are wood exports, foreign aid, and tourism. One million Cambodians work illegally in Bangkok, only 155 kilometers from the Cambodian border. The country needs to invest heavily in education and in building infrastructure. People still use oil lamps and battery-driven TVs.

Cambodia is rapidly catching up to today’s technology and global telecommunications, while trying to revive its traditional art and culture, destroyed by class warfare. It has made big strides in recovering its pre-war tourist industry. New hotels have gone up, such as the Tara Angkor, where we stayed; roads are under construction; people are friendly and eager to please visitors. Angkor Wat is a major attraction, drawing 5000 visitors a day. Added to these is the beauty of the landscape, with tropical fruit and flowers everywhere. I thoroughly enjoyed our journey of discovery to this bucolic part of Southeast Asia.

→ Thailand