April 2005

Our group, reduced from 16 to 10 for the Cambodia extension of the Viet Nam trip, flew from Hồ Chí Minh City to Siem Reap, the closest airport city to the Angkor ruins, our primary destination. Chanta, our Cambodian trip leader, met us following the 60-minute flight on Viet Nam Airlines. On the ride to our hotel his warm and friendly welcome included a handout that concluded “May Buddha be near and protect you on your journey of discovery and spread luck along your path.”

The next morning we departed the hotel at 7 am to beat the heat and the crowds for Angkor, the capital of the Khmer civilization, which ruled from the 9th to the 15th century. Discovered in 1859 by the French, Angkor became an overgrown jungle until 1992, when UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site. Fortunately the Khmer Rouge, whose class war devastated Cambodia for three decades in the late 20th century, did not bomb antiquities; they only cut off stone Buddha heads to discourage religion.

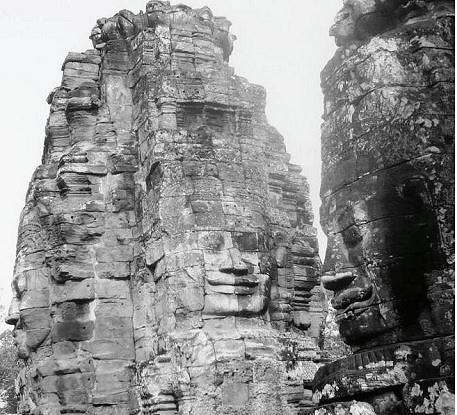

Bayon Temple

Our tour of the vast complex started at Angkor Thom (the Great City), surrounded by a defensive wall and moats. We entered from the South Gate, one of five approached by causeways built across the moat. As we walked down the causeway, we were flanked by 108 large stone figures — on the right 54 gods and on the left 54 demons — all pulling a great snake supported on their knees. We continued on to Bayon, a celebrated temple with a four-faced statue of Buddha built atop a Hindu temple. Other structures we visited were the Hindu temple mountain Baphoun, the Elephants’ Terrace, and the Terrace of the Leper King. The former terrace was used for the king to review his forces and to watch entertainers; the latter was a royal crematorium. Both have elaborate bas‑reliefs. The morning tour ended at the temple of Ta Prohm, ancestor of Brahma.

Along the Siem Reap River we watched a rustic bamboo waterwheel raise the waters into a betel tree trough, which connected to pipes irrigating the nearby fields. Lunch was in the village of Srah Srang, where we enjoyed a meal at a rural home. Our hostess, a 62-year-old woman with nine children aged 12 to 32, cooked for us along with two of her daughters. Dishes we sampled included fish in coconut, and rice balls made of sticky rice and palm sugar. Dropped in boiling water, rice balls float up when done, then cool in cold water. Palm sugar is made by collecting juice from the sugar palm fruit and boiling it with a thickening agent. The villagers excel in woodcrafts that they carve during the monsoon, when they cannot work in the rice fields. I bought a beautiful mobile from a young boy, who had crafted it himself by carving an egret out of wood and hanging it in a wooden frame.

On the way to a sunset view of Angkor Wat, the masterpiece of the temple complex, we visited one of the infamous Killing Fields, where victims of the Khmer Rouge were executed and buried in mass graves. Many of these have been exhumed. In the middle of a garden, a memorial with a tall acrylic glass case contains row upon row of skulls visible from all sides. Buddhist monks live and pray in nearby houses. A plaque on the grounds, often visited by the locals, acknowledges financial aid from Japan.

During Pol Pot’s genocidal regime, Cambodia’s population went from 7 million to 3. Since the end of the war it has risen to 13 million, with an average of five children per family. The genocide mainly targeted the educated elite, thus reducing the country’s literacy rate to 30%. Illiterate rural folk followed Communist ideology more readily, thus escaping the mass murders. However, landmines were everywhere; people used black magic for protection.

Chanta witnessed his father, a policeman, being taken from home, and never saw him again. At the age of seven he was forced to dig ditches and whipped with cables. He became a soldier at eleven and spent his youth at a refugee camp for 360,000 people near the Thai border, where he learned English. Now a tour guide, he is bitter and trusts no one in Cambodia, where even family members turned against each other in the war.

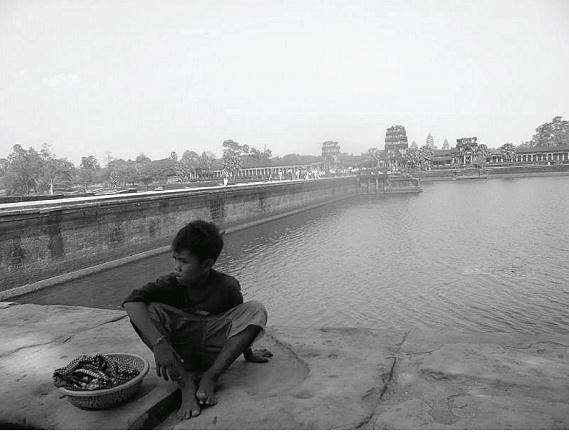

When we reached Angkor Wat it was raining. Although we did not see the Hindu temple dedicated to Shiva in its sunset splendor, our experience of the site was magical. The tall conical towers became apparitions in a shroud of mist; the cobblestone causeway donned a shiny patina; saffron-robed monks dotted the stone landscape. We proceeded along the causeway and entered the central sanctuary, then circumambulated the gallery of bas‑reliefs along the perimeter of the massive edifice, as we viewed the Hindu epic Mahabharata in elaborate stone carvings.

A remarkably executed bas-relief was the Churning of the Ocean of Milk. A huge panel depicted 88 devils on the left and 92 gods on the right churning a sea of milk with a giant serpent in order to extract the elixir of immortality, encouraged by singers and dancers overhead.

Causeway to Angkor Thom

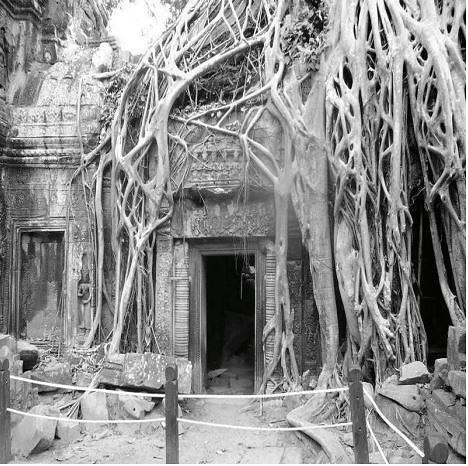

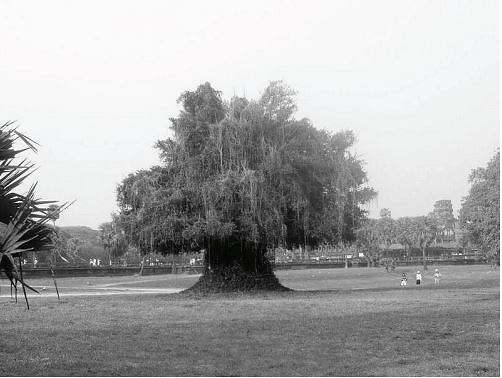

Giant strangling fig tree

Just as astonishing were the spectacular roots of strangling giant fig trees pushing their way through the sand and lava stone walls around us. While these roots crack vaulted passageways, they also bind lintels and cannot be removed. I was so carried away by my surroundings that I ran out of film and approached a vendor nearby. When I questioned his high prices, the young man told me that he paid the police $100 a month to be on the premises, which would otherwise be prohibited.

On the way back to the hotel, we stopped by the roadside to buy a sticky rice snack packed inside hollow bamboo and sold by the stick. Mostly used for sweets, sticky rice is farmed separately from regular rice, the basic staple. Cambodians do not eat much bread except for an occasional baguette, which the French introduced during their rule in Indochina. Vendors sell baguettes in deep baskets or on carts along busy roads.

Our food sampling continued over a buffet dinner and cultural show at the Bayon II restaurant. We feasted on exotic fare, including pancakes with bean sprouts in peanut sauce. The show featured classical court dances in elaborate costumes and headdresses, along with folk dances inspired by the daily lives of fishermen and coconut harvesters. Classical dances suffered badly under the Khmer Rouge regime and are being rebuilt with the support of the current king of Cambodia, Norodom Sihanouk, who returned from exile in Beijing in 1993; he comes from a long line of monarchs going back to the “God Kings” of Angkor. We returned to our hotel by motor trishaw.

On our second day in Siem Reap, we traveled south by oxcart to visit a rural community. Our group of ten split into five carts, as each held two passengers. The owner of each cart took his two guests home for a visit. As we entered the village on a dirt road lined with huts, in front of each hut was a makeshift table covered with flat pieces of fish left in the sun to dry. Here most people made a living from fish, either by catching and drying it or bottling it as sauce. After our host unhitched his two oxen from the yoke, he handed them over to his brother for feeding. Then he introduced us to his grandfather, who at 74 seemed to have resigned himself to passing time by sitting in the shade. Our host’s parents were at the market. We walked around the spirit house to go upstairs and entered a one-room hut on stilts. There were pictures of family members on the wall, and mats serving as bedding neatly stacked in a corner. Here people practice home medicine by squeezing and cupping areas in pain.

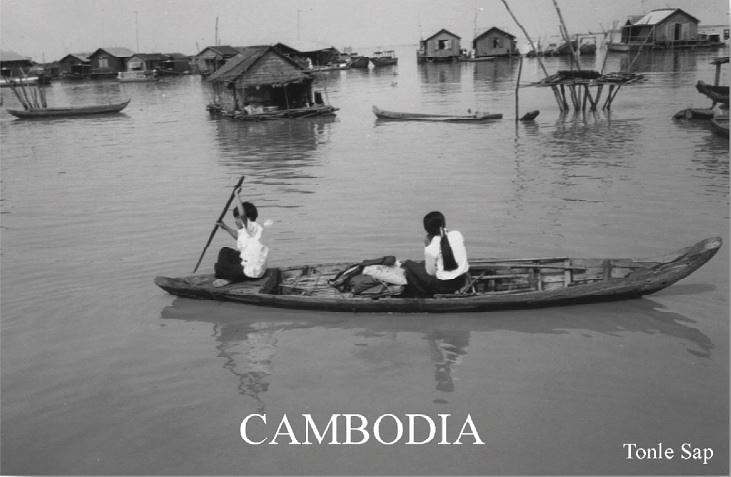

Our excursion south continued to Tonle Sap, Cambodia’s great lake, which expands greatly during the rains at its basin on the Mekong, causing residents to move their homes up to fifteen times a year. We walked along a narrow causeway fringed by houses on tall stilts, all surrounded by plastic trash, and arrived at a fishing village, one of 170 around the lake. In this village of 5000 every shack had a TV antenna. Exploring the settlement by boat was a fascinating experience. Our boat followed a fairly wide main thoroughfare, with narrow passages between houseboats and extensive fish traps. The lake is a sanctuary for birds and home to 107 kinds of fish; yet it is not deep. Boat propellers churn up the rich silt, spewing pieces of brown sediment into the air.

On the boat route we passed by a floating Catholic Church and a community center where decorations were going up in preparation for a wedding reception. We disembarked at a floating school where children arrived by rowboats, the older ones transporting the younger ones. The one-room schoolhouse had two rows of long desks with seven students at each, totaling 70 students from first through fourth grade. We distributed notebooks and pencils to all; but not having anticipated the numbers, we did not have 70 of the same item to go around. Our guide called upon a few pupils, who volunteered to say something in English. These children went to school four hours a day, six days a week, alternating morning and afternoon shifts. At recess they bought snacks from vendors who arrived by boat. Children in neat uniforms rowing from their houseboats to school are among my many memorable images.*

* See postcard image at beginning of article.

In the afternoon we traveled to the Banteay Srei Temple 30 kilometers northeast of Siem Reap. Due to poor but scenic roads, it took us an hour and a half to reach the temple. Along the way we stopped to view mango, guava, and cashew trees, and visited country people making rice wine. Banteay Srei, whose name means “citadel of women,” is renowned for the meticulous detail of its classical Khmer statuary. It is a miniature temple complex carved in pink sandstone, with shrines dedicated to Shiva and Vishnu. The main themes of the elaborate carvings are from the Hindu epic, the Ramayana. Buns, loosely draped skirts, and jewelry characterize the female divinities, lances and loincloths the male ones. Some of the best figurines have been taken to the capital city, Phnom Penh, for protection, while others have disappeared to Paris.

Dinner and a traditional shadow puppet theater at the Bayon I Restaurant were the treats of the evening. A unique dish on the set menu was morning glory soup. Cambodian cuisine uses a variety of flowers, a common one being the lotus. Its root is used for making soup, its flower for dessert and jam. As we enjoyed our meal, we watched shadow puppets of monkeys and buffalos in two fables; the third show was a story from the Ramayana.

Our time in Cambodia was brief but packed. Although we did not travel to the major urban center, Phnom Penh, we acquired a good idea of the country and its people. Having worn down the Khmer Rouge and broken their power, the nation is calm under a constitutional monarchy. Its economy virtually destroyed, it has moved away from Communist ideology toward a market economy. Presently the greatest sources of revenue are wood exports and foreign aid. Only 155 kilometers from the Thai border, one million Cambodians work illegally in Bangkok. The country needs to invest heavily in education and in building infrastructure. Having come out of war only within the last decade, Cambodia is trying to catch up to today’s technology and global telecommunications. The whole country has only one ATM machine, which is in Phnom Penh. People still use oil lamps and battery-driven TVs.

Yet things are improving. Cambodia has made big strides in recovering its pre-war tourist industry. New hotels have gone up, such as the Khemara Angkor, where we stayed; roads are under construction; people are friendly and eager to please. Added to these is the beauty of the landscape with tropical fruits and flowers everywhere. I very much enjoyed my journey of discovery to this bucolic part of Southeast Asia.

Majestic tree on the grounds of Angkor Wat

→ China