February 2008

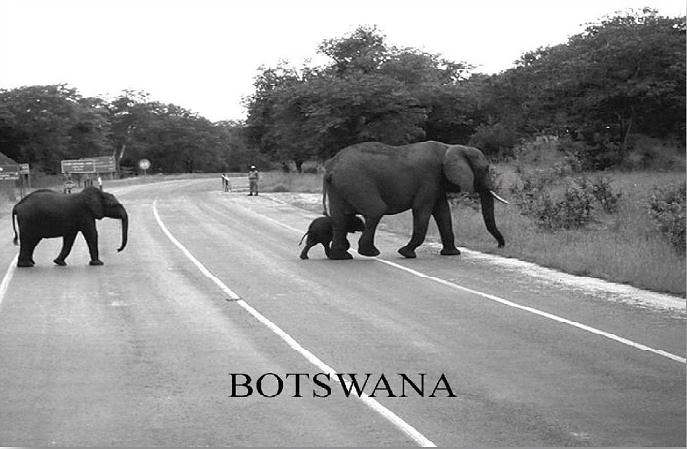

In Victoria Falls, we were met by our trip leader, Mado, with a welcoming smile. Dancers and drummers in native dress greeted visitors at the airport. We traveled by van to Botswana. As part of border control, we had to wipe our feet on a mat sprayed with disinfectant against hoof-and-mouth disease; similarly, our van had to drive through a puddle of pre-sprayed water. On the way to our campsite, we saw storks on trees and cows by the roadside, while elephants with babies crossed our path. Spectacular clouds gave way to a quick shower, cooling the air.

Chobe National Park is the first one created in Botswana by relocating indigenous people, who hunted animals for subsistence and to barter for European goods. Due to conservation efforts the animal populations have increased, stimulating a vibrant tourism industry.

Our campsite was at Baobab Lodge, where we were welcomed by friendly staff singing and dancing. They offered us cool washcloths and juice. We met the managers, nature guides, and serving staff. Reflecting the local heritage, their names covered a full range from African to Western, including Biblical — Kaho, Kelly, and Isaiah, to name a few.

Our rooms, called chalets, were round timber huts with thatched roofs. As protection from wildlife, we were told not to stray off the paths walking to and from the chalets and always to have a staff escort after dark. The camps are owned and run as private concessions by Wilderness Safaris, who train all the staff, including the cooks. Our dinner, one of many delicious meals we had, featured cream of sweet corn soup, roast chicken, potatoes, carrots, broccoli, and salad. Over dinner the staff imitated animal sounds to acquaint us with those we might hear during the night.

The sound of a drum outside our door at 5:30 am was our wake-up call. Following breakfast, including sorghum porridge, we set out for our first game drive in safari vehicles. The group of twelve, dressed in earth tones to blend in with our surroundings, split up into two land rovers with a driver/guide in each. The basic rule of a game drive is to stay seated and calm so as not to attract the animals’ attention. Sudden motion and loud noises can scare them away, or prompt elephants to charge to protect their young.

Our eagle-eyed guide introduced us to the wilderness as he drove. Paths with flattened grass signaled elephants nearby. African savannah elephants are big with curved tusks; mother elephants always walk in front to protect their young. When they walk with their ears out, they are not dangerous. If they make a loud sound and their ears are flat against their heads, they are ready to charge. We were the target of several mock charges warning us to drive off. Then we were distracted by kudus, impalas, and giraffes grazing along the roadside. Unlike the arid land of the dry season, the lush greenery of the savannah now offered these animals plenty to eat. Kudus stood at attention with their ears tuned to catch any dangerous sound; slender impalas stood out with unique black and white stripes on their rumps and tails.

Birds hovered above as we headed to the Chobe River flood plain. Among the easily spotted birds was the lilac-breasted roller, Botswana’s national bird, distinguished by its sixteen shades of blue and its thick beak for eating insects. Others were the European bee-eater, the fish-eating eagle, and the ground hornbill. Cattle and sable antelopes, chestnut-red as well as jet-black, grazed in the open. We drove by baobab trees which had been stripped by elephants, drawn by the water in their fibrous wood. These trees provide bark used to make floor mats, rope, paper, and baskets, and bear a fruit with white flesh used for producing cream of tartar.

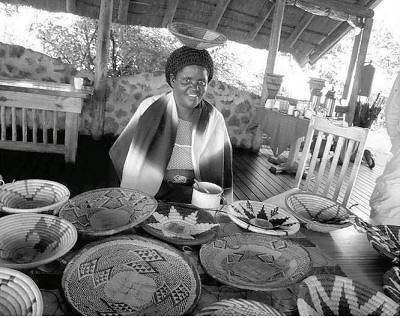

Basket-weaver

After our morning game viewing, we had a buffet lunch of beef lasagna, tuna mousse, sweet potatoes, broccoli, carrots, and a choice of sliced fresh mango, speckled melon, or pineapple. Siesta time was during the heat of the day, followed by tea in the late afternoon. We were then treated to a demonstration by three local women in basket making, a craft all women must master by tradition. Baskets are made by boiling, dying, splicing, and weaving palm or baobab leaves. Bark or root dyes are boiled with the leaves for two hours to attain various colors. The women spread their wares over a long dining room table in the lodge for us to see. The impressive display of baskets in various shapes and sizes was irresistible; I bought one woven with dark leaves against light in a traditional motif.

Our afternoon game drive expanded the variety of animals we had seen in the morning. New sightings included a dead porcupine on the road with its long black and white banded quills detached, grey warthogs with upward-curving tusks, baboons climbing trees, ambling giraffes with blotches of various shades, and majestic cape buffalos and bushbucks grazing near the water. A pod of hippos signaled their presence by creating bubbles on the surface of the river. We waited patiently for a hippo to come up for air, so as to get a glimpse of one of Africa’s big five animals — the buffalo, elephant, hippo, leopard, and lion. We returned to camp just before a thunderstorm, which lasted through the night.

With a picnic lunch, we spent the next morning in our vehicles enjoying the park’s variety of habitats, as well as the various animals and birds attracted to the woodlands, grasslands, and thickets along the river. In the afternoon a cruise on the Chobe River allowed us a close-up viewing of hippos and crocodiles. The river forms a natural border between Botswana and Namibia. While the Botswanan side is a national park, the Namibian side is tribal land, where hunting is allowed. Buffalo and elephants swim across the river from Namibia to Botswana to escape hunters. Chobe National Park is home to 120,000 elephants. Their growing numbers have been destroying the parkland, as elephants topple trees and strip their bark. Our day ended with a braai, an African barbecue. In accordance with local custom, men were served first, after washing their hands with water poured by women from a pitcher.

A lecture provided facts on Botswana, a landlocked country centrally located in southern Africa, 23° south of the Equator. Slightly smaller than Texas, it is surrounded by Namibia to the west and north, South Africa to the south, Zimbabwe to the east, and Zambia with a short border to the northeast. Botswana is a flat country mostly covered by the Kalahari Desert; only 2% of the land is arable, of which 70% is national forest. The majority of the 1.8 million population live in eastern Botswana; most food is imported. Setswana is the local national language, and English is the language for business and written communication.

The earliest modern inhabitants of Botswana were the San (or Bushmen). They lived a hunter-gatherer existence in harmony with nature. They were displaced by various Bantu tribes, the last and largest of which were the Zulus. Boer voortrekkers (pioneers) arrived in 1836, driving 100,000 refugees to the arid northwest. In 1841 David Livingstone came from London to establish a mission school; by 1860 there was a school in every village. 60% of the population is Christian; others are Buddhist or practice traditional beliefs. Originally ruled by local chiefs, the country became a British protectorate in 1885 and gained full independence in 1966. Since then the literacy rate has increased from 10 to 90%. The capital city is Gaborone.

One of the few countries in Africa to choose a market economy over socialism, Botswana has inherited the British system of democratic parliamentary rule. The head of state is the President, who is elected along with fifteen ministers for a term of five years by the 34‑member National Assembly. The House of Chiefs is made up of fifteen chiefs and tribal representatives, who advise the Assembly on proposed laws relating to land usage, as well as social and traditional customs.

Botswana has massive diamond reserves, discovered in 1967. It is the largest diamond producer in the world, with an annual output of 20 million carats. Besides diamonds, gold, wildlife, and tourism, the economy is driven by cattle ranching and some manufacturing. Despite the country’s wealth, health care and welfare for the indigenous population present major challenges. 40% of the country’s population are HIV-positive. 60,000 of the San people, who have lost tribal lands to national parks, are reeling from tremendous social and cultural change, and live largely in poverty.

Our wonderful camp staff sent us off to our next destination with spirited singing and dancing.

→ Namibia