February 2011

Originally scheduled to fly directly from Kolkata to Paro, a change in flight schedule rerouted our itinerary via Nepal, necessitating an overnight stay in Katmandu. As postcard views of Himalayan peaks emerged above the clouds during the 70-minute flight on Air India, I was just as excited at the sight of the majestic mountains as during my earlier visit to Nepal in 2004. Acquiring a one-day visa for $5 and a photo allowed me to clear customs. A local guide met us with a gift of yellow prayer shawls.

Our home for the night was the Gokarna Forest Resort Hotel outside the city. The quiet surroundings and thin crisp air signaled a different world than the one we had come from. As I walked around the premises, the gift shop caught my attention; on a shelf were embroidered suede bags made of yak skin. The bags were decorated with an intricate chain stitch called ari, similar to the vest I had bought in Kolkata. As artisans from Central Asia and Iran settled the Kashmir region centuries ago, Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic traditions started to blend, resulting in beautiful crafts. Ari on yak skin was a Nepalese version of this regional craft, which is created by inserting a small hooked needle through the suede and forming a loop around the hook before pulling the thread back up through the surface of the stitching. Charmed with the looks as well as the practicality of the bag with its shoulder strap, I decided to purchase it, much to the delight of the shopkeeper.

Prayer flags

Early the next morning we flew to Paro on Royal Bhutan Airlines. At an elevation of 7400 feet, Paro, in western Bhutan, has the country’s only airport. Thinley, our guide, and Ugyen, our driver, welcomed us with big smiles; they had distinctive features, with high cheekbones and slanting eyes, and wore the traditional gho — a robe tied around the waist with a cloth belt, called a kera. The light was so dazzlingly clear that I had to reach for my sunglasses. Vertical white prayer flags fluttered in the breeze at a distance.

Before we left for Thimphu, the capital city and our destination for the next two days, we visited the National Museum. At the top of a hill overlooking a valley, the Paro Dzong, or Fort, built for protection from the Tibetans, is a watchtower which has been renovated to house the National Museum. The unusual round building, completed in 1656, is supposed to resemble a conch shell. There is a specific route to follow through the entire building, so that one walks clockwise around important images. No photography is allowed inside.

The fourth floor is the starting point of the exhibitions, which include early stone implements and rock carvings. The implements are described as weapons of naga (snake) spirits, illustrating how magic permeated daily life. The fifth floor of the museum has a collection of thangka art — traditional paintings or embroidery produced in scroll format — depicting Bhutan’s main saints and teachers; the sixth floor houses a philatelic collection. From here a doorway leads to the Tshozhing Lhakhang, or “Refuge Temple,” which offers the protection of different deities to Buddhist practitioners. The lower floor galleries display handcrafted copper teapots, clothes, musical instruments, Buddhist ritual objects, and items captured during various Tibetan invasions, including a rhino shield, a frog skin saddle and a fish scale hat.

During the scenic 90-minute ride to Thimphu, we passed traditional Buddhist houses with painted wood frames, rice fields with oxen, and suspension bridges over sparkling rivers with prayer flags “releasing a prayer to the wind” with each flap. The ride was also an opportunity to learn from Thinley about Bhutan or, as natives call it, Druk Yul, the Land of the Thunder Dragon; the monarch is known as the Dragon King. Bhutan is a constitutional monarchy with an elected assembly and a council of advisors. The fourth king abdicated to his young son in 2008, announcing that the country would become a modern democracy from then on. On November 6, 2008, deemed by sacred astrologers to be a very auspicious day, Bhutan crowned its fifth Dragon King. Across the country people are being educated as to what it means to become a democracy.

Bhutan is dedicated to preserving its past. By law all construction must fit in with the traditional architectural style, influenced by religion; therefore, new cement and brick buildings have decorative wooden window and door frames. Traditional dress is required in temples, in government offices, and at work places; leisure clothing is required at other times. Cigarette sales are banned in the country; no one is allowed to smoke in public places. First-time offenders receive a warning; a second offense is punishable by a prison term of four-to-five years.

National Library

Bhutan has a booming population of 6 million people, the majority of whom is under 25 years old. 98% of the population peacefully follows the guidelines of Mahayana Buddhism. The lavishly decorated National Library in Thimphu is a repository for thousands of Buddhist scriptures. Because of the holy books people often circumambulate the building chanting mantras. Traditional books and historical manuscripts are kept on the top floor; many of these are in Tibetan style — printed or written on long strips of handmade paper stacked between pieces of wood and wrapped in silk cloth. On the ground floor is a copy of the largest published book in the world, entitled Bhutan. One of its illustrated pages is turned each month.

Weaving is a living tradition. The National Textile Museum features exhibitions of weaving techniques, styles of local dress, and various types of textiles with designs and patterns unique to the country, while several weavers work on looms. The shop has exquisite textiles from major weaving centers. All of these use imported wool, silk, and cotton thread, so prices tend to be high.

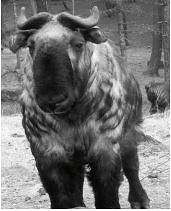

Takin

The takin, Bhutan’s national animal, looks like a cross between a cow and a goat; it has a golden yellow and brownish coat, and grazes on mountainsides. In Thimphu we visited the Takin Preserve, where these animals are kept in a spacious fenced-in area, along with samples of the smallest and the tallest species of deer in the country. The takin is sacred to the Bhutanese and is an endangered species; there is a penalty for killing one. The view of the valley from the hillside is wonderful, with the magnificent Thimphu Dzong (fortress and monastery) below.

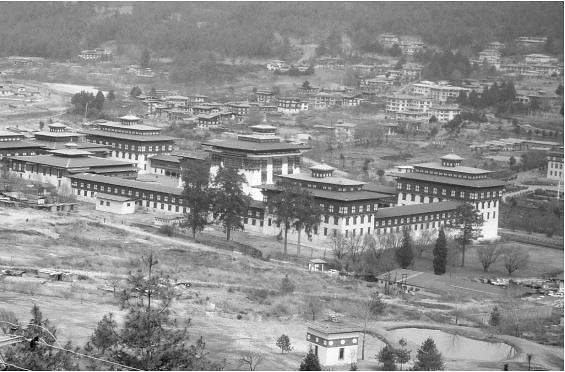

Thimphu Dzong

Our city tour took a detour, due to an e-mail from my friend Astrid Hiemer alerting me to a major art exhibition organized in Thimphu by the Bangladeshi Embassy, along with the Bhutanese Ministry of Home and Culture, and the Buriganga Arts and Crafts center in Dhaka. Astrid was asking me to write about the exhibition for Berkshire Fine Arts, a digital arts and culture magazine based in the US. Fortuitously, the day we were in Thimphu, February 16, was also the day of the grand opening. Based on the enthusiastic response of my seven travel companions, Thinley rearranged our already packed itinerary for the day, making it possible for us to attend the opening at Rapa Hall, a major performance space and gallery.

The gateway to Rapa Hall was festooned in colorful flags, as the exhibition was also celebrating the 31st birthday of King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck on February 21. The king’s birthday is honored with celebrations throughout this Himalayan kingdom over a three-day holiday, during which all offices and schools are closed. Since my birthday was the day after the grand opening, I took this coincidence to be an auspicious sign for me too.

Rafique Sulayman, the Bangladeshi curator of the exhibition, met me at the door and began introducing me to the various dignitaries present, including Ambassador Imtiaz Ahmed and Daisy Ahmed, hosts of the event. The Chief Guest was Lyonpo (a title given to a minister) Minjur Dorji, Minister for Home and Culture, who was accompanied by seven other ministers of the Royal Government of Bhutan. Each minister wore a gho, a traditional outfit for men, and a kabney, or scarf, which identifies rank and is required for formal occasions, including a visit to a temple.

As I spoke to the organizers and met the artists, I began to understand the significance of this exhibition, held in celebration of a Bangladeshi national holiday. In 1947 the new state of Pakistan emerged, combining two distinct territories and cultures, Urdu and Bangla. When Urdu was made the official language of both parts of the country in 1952, unrest erupted in East Pakistan. The government used brutal force to quell protests, killing many students who were defending the right to use their native language. Since then, the massacre has been commemorated each year on February 21, known as Shahid Dibas, or Language Martyrs Day. When Bangladesh finally gained independence from Pakistan in 1971, Bhutan was the first country to recognize the new nation, following a long struggle to preserve Bangla culture and the Bangla language.

February 21 was proclaimed the International Mother Language Day by UNESCO in 1999, in recognition of Language Martyrs Day in Bangladesh and in order to promote linguistic diversity through activities organized in member states. The annual occasion was also formally recognized by the United Nations General Assembly in 2008. The People’s Republic of Bangladesh observes this important historical day, both at home and through its embassies abroad.

Curator Rafique Sulayman is eastern representative of the East-West Artists Association, founded by painter Dorothea Fleiss in Stuttgart. Through residencies, workshops, and exhibitions, affiliated artists share experiences, techniques, and wisdom, contributing to the wealth of international art and understanding. The fifth edition of the exhibition in Thimphu involved artists from ten countries, including one from the US.

Painting by Sukbir Bishwa

The fine art exhibition consisted mostly of paintings, but also included collages, prints, mixed media, wood reliefs, tapestries, and several three-dimensional works. The paintings — in watercolors, acrylics, and oil — ranged from Sukbir Bishwa’s landscapes, inspired by Bhutan’s Himalayan views and traditional architecture, to abstract works such as Dorothea Fleiss’s mixed media “Prayer for a Better World,” in acrylic and black Chinese ink on handmade paper. Christine Tarantino, who identifies herself as a visual poet, had a small collage, where words on bits of paper evoked a spiritual word play. Habiba Akther Papia’s small bronze sculpture, captioned “Sonata of Womanhood,” was a moving commentary on the plight of women. Many of the accomplished artists who had been able to travel to Bhutan were interviewed at the opening, which was well attended by the media.

The opening reception featured an array of Bangladeshi delicacies, accompanied by non-alcoholic beverages. As we thanked our hosts for their gracious hospitality, they also invited us to attend a reception for the artists that evening at Bangladesh House, the ambassador’s residence.

Processing bark

to make paper

Resuming our Thimphu itinerary, we visited a cottage industry for handmade organic paper, used for temple paintings and scriptures. After being softened in water, bark is baked in a hot oven and soaked again. The resulting shreds are sorted into piles, with pieces with dark spots set aside for low quality paper, and submerged in water to obtain pulp. Strained through a rectangular screen frame, the wet sheets are stacked; to keep them from sticking, starch made from hibiscus is spread in between. Finally, the sheets are pressed individually against electric heaters to dry.

Lunch was at a downtown restaurant. The buffet spread included red rice, ground beef, pumpkin, green vegetables, and potatoes au gratin. The only variety of rice grown in Bhutan is red; white rice is imported from India. Likewise all meat, including chicken, is killed by Muslim butchers in India; all dairy products are imported as well. As a Buddhist nation, the Bhutanese do not kill animals; extra prayers are said to make up for the sin of consuming meat.

The National Memorial Chorten, with its sun-catching golden finial, is an important religious structure in Thimphu, built in 1974 in honor of the third king, Jigme Dorji Wangchuck. A chorten is a unique Himalayan type of pagoda, built to commemorate the dead and to ward off evil influences from places deemed “thresholds,” such as strategic points in mountains, confluences of rivers, or forks in roads. The whitewashed National Memorial Chorten has richly carved porches facing the cardinal directions, and features elaborate mandalas, statues, and a shrine dedicated to the popular third king. It is the focus of daily worship for many people. Bundled up against the chill, the faithful stream in, prayer bells in hand, to circumambulate the pagoda, spin the large red prayer wheels, and pray at an outdoor shrine, at the center of which is the statue of a goddess blessing the chorten.

Following this visit, we climbed by car on a newly paved road to the highest point in Thimphu, where the tallest Buddha statue in the country was recently erected. The 169-foot-tall Buddha presides over the city in the sitting mudra, or position, amid the clouds. For people living in the valley of the majestic Himalayas with their eternal shadows, the Buddha, visible from all around, is a source of love and compassion.

A visit to the government-run Crafts Emporium was an opportunity to purchase treasures unique to Bhutan. Here my acquisitions were a beautifully carved and painted round wall hanging depicting the animals of the zodiac with a central yin and yang emblem, and a hand-painted cotton cushion cover featuring Buddhist symbols.

The evening reception at the Bangladesh House was another opportunity to mingle with artists, in addition to seeing them on TV, where the show was billed as the biggest fine art event ever held in Thimphu. A beautifully set buffet table featured specialties of Bangladesh, including pretzel-shaped sweets made with lentil and chickpea flour, deep-fried and then quickly dropped in syrup before cooling. The camaraderie among artists during dinner was a proud moment for multiculturalism. These talented people were honored to be participating in the celebration of such a good cause.

Traffic circle

It snowed overnight, adding to the chill borne by white-gloved police in decorative traffic circle stands, which took the place of lights, and delaying our departure to Punakha in the morning. The Dochu La Pass, which we were supposed to drive through at an altitude of 10,500 feet, was closed due to a landslide.

While waiting for the pass to open, Thinley consulted the book of astrology on our behalf. Buddha Sakyamuni is believed to have allocated a different animal to each month, based on the sequence of their appearance when he summoned them to bid farewell before his passage to Nirvana. The mouse was the first to respond to the Buddha’s call, followed by the ox, which thus became my animal sign for the month of February. As Thinley read from the book, my ox personality was revealed — hard-working, dependable, patient, fair-minded, good at listening, dutiful, unpretentious, wholeheartedly devoted to work, hard to influence, somewhat unreceptive to suggestions, and cool-tempered.

Guard protecting

the porch

As it took a long time to clear the road, we took advantage of our extra time by visiting Simtokha Dzong, Bhutan’s earliest monastery, which has survived as a complete structure since being built in the 17th century. Donning his kabney, Thinley led us through the gate. Leaving our shoes at the foot of the stairway, we climbed up to the hall, which was adorned with colorful puja flags, and unexpectedly happened upon the monks’ morning ritual. Accompanied by gongs, huge pipes, and trumpets, they were chanting prayers to the God of Compassion. Fascinated by this ritual performance, we tiptoed back out the heavily draped door, coming upon scary masks that protected the shrine from demons. Guardians of the four directions adorned the gorikha (porch), while circular thangkas displayed the four levels of the upper and lower worlds.

Finally the road cleared. We drove to the Dochu La Pass along the National Highway on winding, narrow mountain roads through blue pine, maple, and oak trees laced with snow. The scenic climb to the peak was marked by a large array of prayer flags and 108 chortens built in atonement for the loss of life caused by the flushing out of Assamese militants in southern Bhutan in 2003. On a hill just below the pass is the Dochu La Resort, where we stopped for lunch above the clouds that welcomed us to eastern Bhutan. While waiting to be served, we warmed our chilled hands with smooth river rocks, kept warm on the centrally located wood stove, along with a tea kettle and coffee pot. Browsing in the small gift shop, I found a mandala magnet.

Back on the road, we came upon a truck which had slid into a ditch going up the mountain; traffic was blocked, so we had to wait for the road to clear again. Once we were through the pass, the landscape changed; snowy mountains turned to lush forests of lacy pines and firs with occasional rhododendrons. Landslides recalled recent monsoons, and rivers appeared. We descended to the fertile and beautiful Punakha Valley at the junction of the Mo Chhu (Mother River) and Pho Chhu (Father River); at 4500 feet, this confluence is a major source of hydroelectricity and an economic boost to the country’s exports.

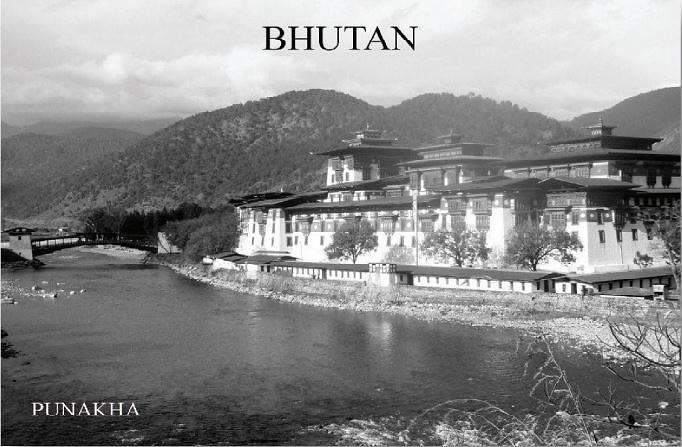

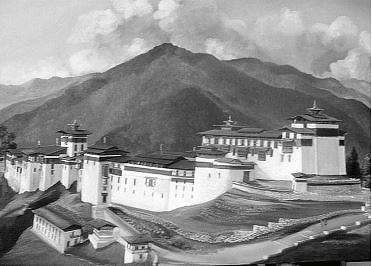

Commanding the river junction is the impressive Punakha Dzong,* where the first king was crowned in 1907 and the third king convened the new Bhutan National Assembly in 1952. Punakha was the first capital of the country; the attractive dzong, built in 1637 with towering whitewashed walls and elaborately painted gold, red, and black carved wood accents, served as the seat of government until 1955.

* See postcard image at beginning of article.

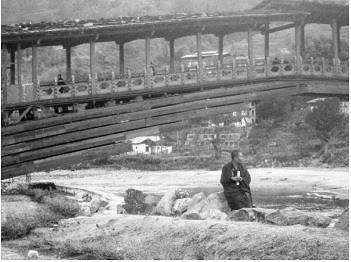

Cantilevered bridge

Surrounded by jacaranda trees at the river’s edge, the building is accessed via a cantilevered foot bridge. A heavy wooden gate leads to a climb up the steep wooden entry stairs, designed to be pulled up for protection against invasion. Buildings with intricately carved and painted balconies, supported by equally elaborate columns, surround the three courtyards of the dzong. The first one is for administrative functions and houses a huge white chorten and bodhi tree. Off the courtyard is a shrine to the queen of the nagas (snake spirits). The second courtyard houses monastic quarters, where religious leaders have their own chambers to view the annual Punakha Festival. The third has a temple; at the southern end is an assembly hall with ceremonial murals, depicting the life of the Buddha from princehood to enlightenment.

Grateful to be at such a beautiful spot on my birthday, I looked forward to settling down at the Punatsangchhu Cottages in Wangdue (also called Wangdi), 30 minutes from Punakha and our home for the evening. My room had a small electric heater and an unheated bathroom. Forgoing a shower, I put on many layers, topped with a pashmina shawl I had picked up in India. Shortly after I entered the dining room, waiters arrived with a personalized birthday cake, along with a gift from the manager and hotel staff — a wine bottle cover shaped like a local woman’s dress known as a kira, which is made of bright-colored, finely woven fabric with traditinal patterns.

In the morning we drove to the Wangdue Phodrang Dzong in the historic center of Wangdue. Built in 1638, the dzong is sited dramatically at the end of a ridge above the river with commanding views of the valleys below. Its complex shape consists of three separate narrow structures that follow the contours of the hill. There is only one entrance, reached by a road that leads downhill from the central market in town. A large sign at the entrance informs visitors that a conservation project supported by the Indian government is underway and slated to be finished in 2013.

Wangdue is a small town with a ramshackle, but untouched air. It is a town of whitewashed wooden shops with plain brown window and door frames. The general shops along ancient stone sidewalks are crammed with goods that spill out of narrow windows in jars or dangle from strings. The houses have roofs of slate mined on nearby hills and held down by river rocks. Farmers crowd the central market with baskets of produce and squat on the ground bundled up, catering to customers who are equally bundled up, because of the town’s location on an exposed promontory overlooking the river.

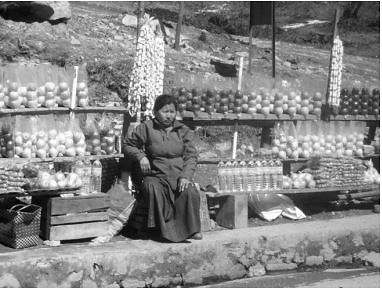

Roadside vendor of

yak cheese and apples

Returning from this excursion, we drove by a new structure being built with hand tools; another one was newly consecrated, its colorful ribbons swaying in the wind. We stopped by a roadside stand to become acquainted with yak cheese, which is sold in small squares on a string. It is softened in hot tea and sucked like a caramel. None of us could master the technique, and we decided yak cheese was an acquired taste. A common sight in Bhutan is archery, the country’s national sport. Men wear ribbons around their waists indicating the color of their team during tournaments; women stand on the sidelines to cheer.

Heading back to Thimphu, we passed the king’s convoy of eight cars and were told not to take any photos. He was on his way for a visit to the military; Bhutan has a volunteer army of 10,000 soldiers and no air force or navy. The king travels extensively, especially to poor areas, making sure all his people have shelter and food. By giving land, he aims to ensure that no one lives in poverty and everyone has a certain standard of living; in turn the people love him. He has equal status to the religious patron of each city; his picture is in every temple. The deeply spiritual populace lives in harmony with nature, guided by the philosophy of Gross National Happiness (GNH), derived largely from their religious and cultural heritage. Content subjects make for a stronger kingdom.

The snow of the previous day had cleared up around the Dochu La Pass. Traffic moved with ease, until there was an accident. Two taxis collided while trying to pass one another on the narrow mountain lane. Fortunately, the drivers’ dispute did not last long and they were able to settle their case without help from the police. We stopped for lunch at the Orchid Restaurant in Thimphu; the buffet included red rice, chicken with bones (boneless meat is very expensive as it is imported), spaghetti, potatoes, carrots, and green beans.

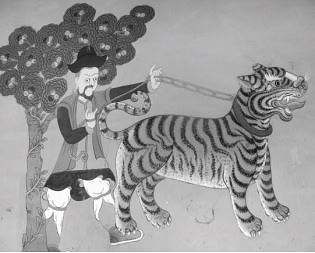

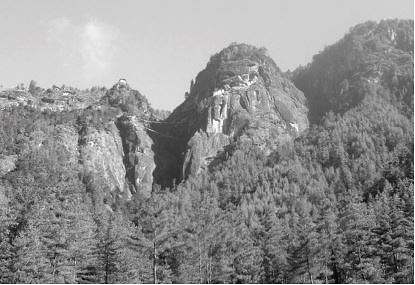

Tiger guarding courtyard entrance, Rinpung Dzong

Returning to Paro for our final two nights revealed further natural and cultural treasures. The Rinpung Dzong towers over the town and is visible throughout the valley. Built in 1644, this fort was used on numerous occasions to defend the Paro Valley from Tibetan invasions. Now, like most other dzongs, it houses both a monastic body and district government offices, including the local courts. It is built on a hillside, dotted with weeping cypress, the national tree. The Bhutanese flag — diagonal wide bands of yellow and orange with a dragon image where the colors intersect — flutters outside.

Due to the steep angle of the hill, the front courtyard of the administrative section is higher than the courtyard of the monastic quarter. A road climbs to the northern entrance, which leads into a third-floor courtyard, guarded by painted images of a yak and a tiger and housing a five-story-tall utse, or central tower. Richly carved wood — painted in gold, black, and ochre — and towering, whitewashed walls serve to reinforce the sense of power and wealth. A stairway leads down to the monastic quarter; the large prayer hall has exterior murals, while the interior is rather plain, except during visits by dignitaries.

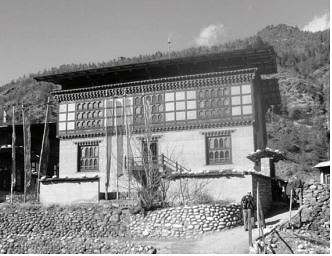

The Village Lodge

After entering Paro across a traditional covered bridge, we walked through the center of town, browsing craft shops. Then we drove to the village of Tsendona, where our hotel, the Village Lodge, was located. Leaving our luggage on the bus, we walked to the hotel, which is at the end of a country path too narrow for vehicles. Symbolizing the elements, five different-colored prayer flags on poles fluttered in the wind in front of the building — white for water, yellow for earth, blue for sky, red for fire, and green for nature. Staff met us in the lobby with warm washcloths, tea, homemade cookies, and roasted rice, a common local snack.

In the morning, dressed in layers, and some with walking sticks, we drove to a parking lot for a hike up to the Taktshang Goemba monastery. The name, which means “the Tiger’s Nest,” stems from a legend according to which Guru Rinpoche flew to this site on the back of a tigress to subdue the local demon, and meditated in a cave here for three months. The monastery, perched at an altitude of 9500 feet, was built in 1692 and is considered a holy place, attracting pilgrims from all over Bhutan.

Tiger’s Nest

The hike, a major point on any tourist itinerary, provides spectacular views of snowy mountains, lush forests, and rivers lined with stones rounded by running waters. The trail climbs through blue pines, then switches back steeply up the ridge, where a sign welcomes visitors to “Walk to Guru’s Glory! For here in this kingdom rules an unparalleled benevolent king.” At a strategic point on the road a small chorten with a large prayer wheel beckons the devout to give it a spin, while prayer flags nearby sway in the wind. A short walk away is a teahouse with an impressive view of the monastery. Starting at 4500 feet and climbing to this point at a height of 8500, our ascent took an hour and a half. The four of us who arrived first were welcomed by vendors and their children with cherubic faces and pink cheeks. I could not resist the pleas of individual vendors, although they sold similar items. So I patronized four of them, buying a chunky turquoise and coral bracelet, a small prayer wheel, a mask, and a woven wall ornament.

After a few photos with the Tiger’s Nest as a backdrop and a well deserved cup of tea, we began our hike back down. Thinley advised us not to extend our climb for another 1000 feet, as the rest of the trail would have involved descending to a waterfall before climbing up the other side of a deep chasm to the monastery entrance. Hiking back for another hour and a half, we reached Paro, where we had lunch — goulash, rice, potatoes, fried fish, fried zucchini, cole slaw, and apple fritters for dessert.

A short drive from Paro is Kyichu Lhakhang, a seventh-century temple and one of Bhutan’s oldest. This temple is paired with a new one, Guru Lhakhang, which was built under the initiative of the Queen Mother in 1968. The temple complex has chortens in memory of important masters, a shrine to the Buddha, sacred sculptures, and fine thangkas of eight bodhisattvas, including the God of Compassion with his multiple heads and eyes for better protection of other beings.

On our final night in Bhutan, Ugyen sang country songs for us, playing the drum yen, a folk string instrument he had crafted himself. Occasionally Thinley joined him in song. In answer to a question as to the origin of their given names, we received the following explanation: A newborn baby is believed to be protected by the gods during the first three days of its life; on the fourth day the baby is taken to a temple to be blessed and to receive a name. There is a book of 40 names, each attached to a string, which the priest pulls, thus naming the child. Thinley and Ugyen are very common names; nowadays families give children a second name. Within the context of Bhutanese culture, this answer was no surprise, as standing out as an individual is not looked upon favorably. To brag about wealth is punishable by law. The wealthy, such as hotel owners or people who make money from the steel industry, must share their wealth with those less fortunate.

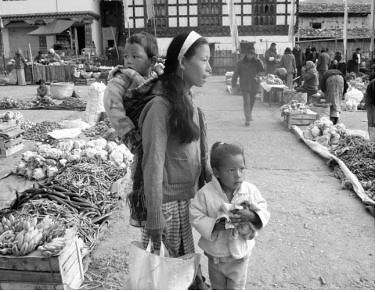

Family at the

Sunday Market

Fortuitously, our departure fell on the same day as the Sunday Market, giving us the opportunity of a close look at some of Bhutan’s unique local products. Strings of chugo (dried yak cheese), either white (boiled in milk and sun-dried) or brown (smoked), were spread out before men and women in wool sweaters and caps, sitting cross-legged on the ground. Baskets of betel leaves and nuts imported from India sat next to jars of pink paste containing lime, which is eaten along with betel nuts. Brooms, a variety of greens, potatoes, rice, cauliflower, eggplant, and chili peppers and powder were all plentiful. However, 70% of all consumables are imported, as no goods are processed in Bhutan. Tea comes from Sri Lanka, mango and apple juice from Thailand; potatoes sold to India come back as chips.

As I bid farewell to beautiful Bhutan, precariously wedged between China and India, I thought it was fortunate that the country had remained isolated for centuries; democracy and the 21st century have arrived, but bringing with them modern problems such as AIDS, alcoholism, crime, and drug abuse. As this peaceful and seemingly happy country incorporates the benefits of globalization, may it retain its identity and culture, along with its sense of optimism and hope.